Klee’s Birthday Party

It was the fall of 1972, and I was driving Anni Albers down the Wilbur Cross Parkway from my family’s printing company in Hartford, Connecticut, back to her and Josef’s house in the New Haven suburb of Orange. The Alberses—she was seventy-four, he eighty-five—were the last two surviving members of the Bauhaus faculty. I had been introduced to them two years earlier, and was now working with Anni on a limited edition print in which she was making ingenious use of photo-offset technique that was generally applied to commercial lithography rather than abstract art.

Anni and I were in my two-seater hatchback car, an MGB-GT which the Alberses praised as an exemplar of the Bauhaus ideals of impeccable functioning and no wasted space. “We prefer good machinery to bad art,” Josef had explained. But the torrential rain that afternoon was so intense that Anni was an anxious passenger. “Please pull over under that bridge until the downpour gets lighter,” she requested in her German-accented English, the controlled politeness barely masking an inner desperation. “In Mexico, when we would go there in the thirties with friends in their Model A, we often had to pull over during storms,” she added, to make it clear that she was not criticizing my driving.

The cascade of rain on the windshield was intensifying and the visibility was becoming dire as I stopped the car. Under one of the charming carved stone parkway bridges built by the WPA, Anni momentarily closed her eyes in relief. She was an adventurer—luring Josef from the Dessau Bauhaus to Tenerife for five weeks on a banana boat in the 1920s, getting them to Machu Picchu in the fifties—but she also was chronically anxious, which she directly attributed to the period in 1939 when she had to get her extended family out of Nazi Germany; her parents’ ship docked in Veracruz, in Mexico, where she and Josef had to scramble to bribe one person after another before Anni’s increasingly desperate mother and father finally managed to disembark. At twenty-four, I was soaking up Anni’s life experiences as if they had been my own, and was enchanted by the consuming dedication she and Josef had to the making of art and by the way their work enabled them to withstand anything. Now, in the sports car under the bridge, the woman who had become director of the Bauhaus weaving workshop assured me that our journey had been worth its challenges because of her thrill at supervising the presswork of her latest prints, and the importance of her being there to oversee the mechanical adjustments that intensified the tonality of the gray ink.

Josef Albers, photo of Anni Albers. Anni disparaged her own looks; others considered her a great beauty. This is one of the many pictures Josef took of her over the years.

I had switched the motor off. Anni turned to me and said with a smile, “You deserve a reward. I know you have been wanting to hear about Paul Klee for a long time.” Since our first meeting, I had badgered her with questions when either she or Josef mentioned Klee, Kandinsky, or their other colleagues. Both the Alberses, however, were so focused on their current work and uninclined to nostalgia that I had not been able to elicit more than a few cursory remarks. “I will tell you something I have never told anyone before—about his fiftieth birthday.” It was 1929. Klee, Anni told me, was her “god at the time;” he was also her next-door neighbor in the row of five superb new masters’ houses in the woods a short walk from the Dessau Bauhaus. Although the Swiss painter was, in her eyes, aloof and unapproachable—“like Saint Christopher carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders”—she admired him tremendously. She had even acquired one of his watercolors after being bowled over by an exhibition in which Klee tacked up his most recent work in a corridor of the Bauhaus when it was still in Weimar. The purchase had been a rare public admission of her family’s wealth, which she normally concealed: she told me that she had been so embarrassed by the appearance in Weimar of two of her uncles in a Hispano-Suiza that she had begged them to drive off immediately. But though her ability to buy the painting conspicuously set her apart from the other students in difficult economic times, she still could not resist acquiring Klee’s composition of arrows and abstract forms. Now, as her god approached his major birthday, Anni heard that three other students in the weaving workshop were hiring a small plane from the Junkers aircraft plant, not far away, so that they could have this mystical, otherworldly man’s birthday presents descend to him from above. He was, they had decided, beyond having gifts arrive on the earthly level where ordinary mortals live.

Klee’s presents were to come down in a large package shaped like an angel. Anni fashioned its curled hair out of tiny, shimmering brass shavings. Other Bauhauslers made the gifts the angel would carry: a print from Lyonel Feininger, a lamp from Marianne Brandt, some small objects from the wood workshop.

Anni was not originally scheduled to be in the four-seater Junkers aircraft from which the angel would descend, but when she arrived at the airfield with her three friends, the pilot deemed her so light that he invited her to get on board. For all of them, it was their first flight. As the cold December air penetrated her coat and the pilot fooled with the young weavers by doing 360-degree turnabouts as they huddled together in the open cockpit, Anni became suddenly aware of new visual dimensions. She told me she had been living on one optical plane in her textiles and abstract gouaches. Now she was seeing from a very different vantage point, with the factor of time added in. She was too fascinated to be afraid.

She guided the pilot by identifying the house the Klees shared with the Kandinskys next door to her and Josef. Then he swooped the plane down and they released the gift. The angel’s parachute didn’t open fully, and it landed with a bit of a crash, but Klee was pleased nonetheless. He would memorialize the unusual presents and their delivery in a painting that shows a cornucopia of gifts on the ground in good condition, even if the angel looks a bit the worse for wear (see color plate I). James Thrall Soby, who owned the colorful canvas, told my wife and me that he thought it depicted “a woman passed out drunk at a cocktail party,” with the golden brushwork Klee used for Anni’s brass shavings representing the socialite’s blond hair, but Anni’s account revealed the actual facts.

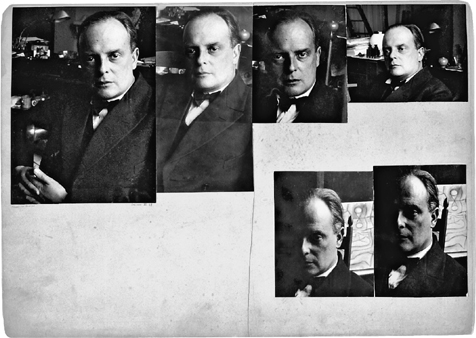

Josef Albers’s photo collage of Klee in his studio at the Dessau Bauhaus. Albers’s portrait photos were scarcely known until after his death in 1976.

Josef Albers was less impressed than Klee was. Later that afternoon he asked Anni if she had seen “the idiots flying around overhead.” Anni smiled mischievously as she recalled this. “I told him I was one of them,” she said with her usual tone of proud defiance.

The rain let up, and we resumed our drive. This was America in the heyday of Pop Art, a time when the newspapers reported daily about what parties Andy Warhol and Baby Jane Holzer had gone to the night before; while that sort of current gossip held no interest for me, every morsel about Bauhaus life had a glow. Listening to Anni in her newly expansive mood as we headed home, I began to see that the geniuses of the Bauhaus lived with the creativity and flair of their work.

Yet at the same time that these painters, architects, and designers were having extraordinary impact and leading unusual lives, they were subject to the same needs and fears and longings as most human beings. As I spent more time with Josef, too, he made clear both the pleasures and the struggles of his colleagues, so that I had at least a tiny glimpse of their everyday realities as well as their exceptional lust for improving the seeable world. A reverence for the universe, a profound dedication to adding to its beauty—these were constant, but so were the inescapable realities of money and family and health.

ANNI ALBERS WAS SOMEONE who was not used to confiding in another person, possibly not even in Josef, and she clearly had a lot bottled up that she wanted to say. Although she seemed full of certainty, there was much that made her uncomfortable. Once our friendship helped assuage her own feeling of inadequacy, Anni described a slight that had stung her nearly a half century earlier, but that, until she told me about it, she had kept to herself.

Shortly after the Alberses had moved into one of Walter Gropius’s splendid, flat-roofed masters’ houses at the Dessau Bauhaus, Josef, who by then had a high rank on the faculty, told her that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, Mies’s mistress, would be coming for dinner. Eleven years her husband’s junior, still a student in the weaving workshop, and not someone who was ever sure of herself socially, Anni wanted to do everything right. By then she and Josef had been married for three years, but she still felt like a new bride who wanted to make the right impression on her husband’s cohorts. Besides, Mies already had a reputation as one of Germany’s most important architects, and both Alberses admired his work immensely.

Anni’s mother had given her a butter curler. In the luxurious Berlin household in which Anni had grown up, family members never entered the kitchen, which was strictly reserved for staff, but when dinner was laid out on the heavy, carved Biedermeier table in the ornament-laden dining room, butter balls were part of the landscape, and Anni knew how they were made. Preparing for dinner that evening in Dessau, she carefully used the clever metal implement to scrape off paper-thin sheets of butter and form them into graceful, delicate forms resembling flower blossoms. It was the sort of process and manipulation of materials she prized, and which she often discussed in explaining her textile and printmaking work. Like weaving, the making of butter balls required the careful stretching and pulling of a simple substance with the correct tool, to achieve a transformation. The resemblance of the result to a flower was at odds with her usual concept of nonrepresentational design, but it amused her in this rare instance.

Mies and his imperious female companion arrived. They had not even removed their coats or uttered a word of greeting before Reich, glancing at the table, exclaimed, “Butter balls! Here at the Bauhaus! At the Bauhaus I should think you’d just have a good solid block of butter!”

Josef and Anni Albers with Wassily Kandinsky on the grounds of the Dessau masters’ houses, ca. 1928. After the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, the masters and their wives were thrilled to live in the new houses Walter Gropius had designed for them. Josef Albers and Wassily Kandinsky often took walks in the woods together.

It was a sting Anni Albers remembered word for word half a century later. But the significance of Lilly Reich’s remark was not just its nastiness. The incident involving the form of butter on the dining room table exemplified the way that every detail of how we live, every aesthetic choice, affects the quality of daily human experience. That idea, as well as the significance of individual personalities, was, I was beginning to see, the crux of the Bauhaus.