Within hours of carefully packing the million dollars into its custom-made canvas bag, the FBI arranged for the printing of a 125-page “book” that lists the serial number of each of the fifty thousand twenty-dollar bills. Within days of the kidnapping, the little books are on their way to banks, stores, and other institutions and outlets around the United States. Ginny’s ransom is the hottest money in the country—yet in the days and weeks following her abduction, no one reports seeing any sign of it.

The owner of a Mr. Steak restaurant in Golden Valley describes to agents a man he says he saw place something at the base of the signpost at Louisiana and Laurel Avenues on the evening of the ransom delivery. Carl Miller was taking a break at the time and saw a stocky middle-aged white man bearing a “determined look, a look of urgency” drive through the parking lot and stop at the signpost. His description becomes a sketch that the FBI sends out to horse- and dog-racing tracks and other legal gambling establishments around the country. The Bureau believes the man or men trying to spend or launder the loot could be anywhere by this time.

In early August, an unnamed Minneapolis police investigator articulates for the St. Paul Dispatch what is likely the prevailing wisdom at the moment: Whoever kidnapped Ginny Piper has long since left the state. “If those guys were smart enough to get one million dollars in the first place, you can be sure they are smart enough to know they can’t spend it here,” the detective tells the paper. “Unless they expect to bury the loot and keep it under cover for at least the next six years, while trying to live normal lives in the meantime, they have no reason for being in the state [almost two weeks] after the kidnapping.”

But just how “smart” are the Piper kidnappers?

The question becomes a hot topic of conversation when the FBI discloses that the green Monte Carlo recovered after Bobby delivered the money is the same vehicle the kidnappers used to drive Ginny up north. Who but a knucklehead would use the same car coming and going when every cop in five states would be looking for it within an hour of the abduction?1 Who would decide to pull the job on the one day of the week the Pipers’ cleaning women are routinely on the premises and when Tad Piper and his family are temporarily living there? Who, for that matter, would decide to hide the Upper Midwest’s most sought-after individual in a popular state park during the height of the summer-vacation season? The questions suggest the participation of either lucky amateurs or holy fools.

Whoever they are and whatever their qualifications, they have gotten away with a fortune. So far. “Hell, they’ve got the one million dollars,” another cop tells a reporter. “They can’t be all that dumb.”

The money, by the way, was not simply handed over to Bobby with a handshake and a sympathetic smile, though the casualness of the transaction speaks volumes about the way business is conducted within the Twin Cities’ old-boy network of the era.

As with many details of the Piper case, there is more than one explanation.

Almost thirty years after the fact, George Dixon tells Harry Piper III, “At the very conclusion of [the preparations], it dawned on me that Bobby owed us a million bucks.” Whereupon, Dixon said, he produced a yellow legal pad and asked Bobby to write, “I owe the First National Bank of Minneapolis $1 million,” and sign it. “Which, of course, he did.” Another, less authoritative telling has Bobby jotting an impromptu IOU on a scrap of notepaper or the back of an envelope à la the Gettysburg Address.

Whatever the documentation (which has long since disappeared), it is good enough for Dixon, and Bobby, to no one’s surprise, will prove a man of his word and pay back every penny.

The FBI is in a full-court press.

Richard Held, in charge of the Minneapolis office, tells the papers that his agents have received what seems like “a million leads.” He is probably not exaggerating too much. This is the most talked-about crime in these parts since the gruesome murder of Carol Thompson in 1963,2 and every other Twin Citian seems to have seen or heard something about the Piper case or knows someone who has.

Held assures the press that his agents are working twelve-hour days, seven days a week, and will check out every tip “no matter how illogical it may appear on the surface.” Held tells a reporter, “We’ve made this town so hot even the hoodlums are bitching.”

But the feds, rarely bothering to hide their contempt for the press, share almost nothing in the way of specifics. The Minneapolis office reveals little about the physical evidence the agents brought back from Jay Cooke State Park. Dozens of items were plucked out of the underbrush at the site where Ginny was held, some of the items days or weeks after the rescue. The material comprises the handcuffs, eight-foot-long chain, and padlock used by the kidnappers, as well as a blue sweatshirt, a couple of large pieces of green plastic sheeting, and a Piggly Wiggly supermarket shopping bag. Which of several other items—including a Kool cigarette pack, an empty wine bottle, and a can of Off! insect repellant—might be connected to the case and which are the random detritus of a public park has not been determined.

None of the four handguns that Ginny and her housekeepers said the kidnappers brandished has either been found or identified as to make or type. At the agents’ behest, the three women paged through several gun catalogs without making a positive ID. Ginny, who admitted she knew even less about guns than she knew about cars, told investigators that she thought her abductors’ guns were brown, a color not usually associated with firearms of any kind.

In August, rumors circulate about the discovery of ransom money in a north Minneapolis junkyard. One of the sources quoted in a Dispatch story is DePaul Kondrak, who runs Brother DePaul’s House of Charity, whose secretary received the second of the two calls revealing Ginny’s location on July 29. Kondrak tells the paper that three different individuals have told him that Piper money has been found in the neighborhood dump. While he personally has not seen any of the twenty-dollar Treasury notes, he says he is sure that the rumors are credible.

Agents paw through the junkyard and its immediate surroundings, but find nothing.

Out of the media glare the FBI tracks down and speaks to hundreds of possible suspects, ranging from inmates at the state prisons in St. Cloud and Stillwater3 to the freelance help who occasionally tend bar at the Pipers’ parties or manicure the landscaping in their Orono neighborhood. The agents draw heavily, of course, from UNSUB 1’s biographical commentary as related by Ginny, despite their doubts about the man’s veracity.

Inmates, acquaintances, and other possibilities matching either of the UNSUBS’ descriptions, who have an alcohol or drug problem, sore knees, a background in construction work, and a familiarity with the Sportsman’s Retreat and/or Jay Cooke State Park, who have spent time at St. Cloud reformatory or the Anoka State Hospital, missed work between July 27 and July 29, own a bar in Minneapolis, and have been known to be called “Alabama,” “Tom,” or “Chino,” are tracked down and interviewed. So is anyone with a personality or characteristics that would lead an acquaintance to believe that the individual is “capable of the Piper kidnapping.”

Law enforcement will be interested, reasonably enough, in anyone of previously modest means who, sometime after July 29, started spending large amounts of money on homes, cars, boats, horses, or exotic vacations, or who abruptly quit his job and/or dropped out of sight.

Not surprisingly, given the breadth and open-endedness of the investigation, the number of persons on the Bureau’s suspect list soon exceeds a thousand. Most, such as a pair of minor-league felons named Kenneth Callahan and Donald Larson, have criminal records. Many, though, are men whose names have bubbled up because they once drove a green Monte Carlo, are known to camp in northern Minnesota, have a wad of extra cash in their pocket, or run their mouths off about the case while drinking with buddies. There are a few intriguing possibilities, but most of the names are fed by a barfly’s rumor, an ex-wife’s spite, or an inmate’s desire to lessen his hard time. Among the more exotic “suspects” is the mobster Salvatore (aka “Rocky”) Lupino, pro wrestling icon Verne Gagne, former Minneapolis mayor and convicted fraudster Marvin Kline, and American Indian Movement leader Clyde Bellecourt, none of whom is considered seriously for very long by investigators.

The dragnet, from its beginning, is a labor-intensive grind with, quantitatively, few precedents in Bureau annals. There are no reported car chases or kicked-in doors. Though there are plenty of informers, no concrete-encumbered snitch’s corpse is pulled out of the river. The sweep has resulted in “many, many” arrests in connection with other crimes, Richard Held boasts to reporters, but that has to be small consolation to the dozens of agents running down leads in the Piper case. The late sixties and early seventies have been terrible years for the FBI, with revelations of break-ins, spying, “dirty tricks,” and other unlawful activities vis-à-vis antiwar activists and civil rights leaders, as well as unprecedented scrutiny and criticism from Congress and the press. Several high-profile crimes, including the “D. B. Cooper” skyjacking, the Watergate burglary, and the theft of some of its own most sensitive files have taxed the Bureau’s resources and damaged its vaunted crime-fighting reputation. Would the Piper case become another conspicuous embarrassment?

Meanwhile, theories abound and sometimes make the papers.

George Scott, the Hennepin County Attorney, hits the Star’s front page in August when he cites parallels between the Piper case and the 1968 Barbara Jane Mackle kidnapping in Georgia. Scott has read a book on the case—83 Hours ’Til Dawn, which was made into a network television movie—and suggests that the Piper kidnappers were inspired by the book and learned enough from it to avoid the mistakes that eventually tripped up the young woman’s assailants. Scott says in both cases the kidnappers took their victim to a wooded area some distance from the abduction site (they buried Barbara Jane alive in a coffin-like box equipped with a ventilator), demanded that the ransom be delivered in twenty-dollar bills, and used a clergyman to contact the authorities. In both cases, after the ransom was delivered, the victim was safely returned to her family.

Scott says the FBI should look into who has checked 83 Hours ’Til Dawn out of the Minneapolis public library system during the past several months. When queried, Richard Held says his agents have already reviewed the Mackle book and that Washington has sent him the case files. He isn’t sure whether anyone has looked into the library connection.

Sometimes the investigators probe uncomfortably close to home.

During one of their early conversations, agents ask Ginny to describe UNSUB 1’s voice. The man’s voice was kind of rough, she says. And, perhaps for the benefit of Bobby or one of her sons sitting in on the conversation, she compares it with the voice of an old friend and neighbor. She isn’t saying it was the neighbor’s voice or even sounded a lot like it—only that it was somewhat similar to his. But that’s enough for the Bureau to add the neighbor’s name to the list of possible suspects and to nearly ruin a long friendship.

In another instance, investigators learn—it is uncertain exactly how—about angry comments made during an evening of heavy drinking a few years earlier by a young member of the Pipers’ extended family. The comments had to do with a dispute about family money that infuriated the young man to the point where he threatened revenge on Bobby and Ginny. The allegations, though dated, are specific enough for agents to give the young man a series of grillings.

When they learn that the relative has made the FBI’s suspect list, the Pipers summarily dismiss the possibility of his involvement. But, unfortunately for the young man, the Pipers are not the keepers of the list.

The Pipers did not, on July 27, 1972, have a home safe or a burglar alarm or any of the other security devices, technologies, and personnel that wealthy people are presumed to have had in this day and age. The only weapon on the premises was the twelve-gauge shotgun that Bobby kept in the attic between his bird-hunting trips. The family’s amiable golden retriever was neither seen nor heard when the men made off with Ginny.

The Pipers have money and enjoy the perquisites that come with it: the Woodhill memberships, the European ski trips, the winter getaways to the Bahamas, elite schools for their children. What they are not, though, is ostentatious. Theirs is old money, assumed if not taken for granted by successive generations of its owners, who generally believe they have nothing to prove to their neighbors. Showing off is in poor taste and left to the newer rich with their pretentious mansions and flashy cars.

Bobby, who drives himself to work in a year-old Oldsmobile, is happy to tell friends he didn’t pay extra for the AM/FM radio. The Olds is a large and handsome sedan, but probably not the car you would expect the chairman of a major financial institution to drive. Ginny drives a four-door Buick that her kids refer to as the “Living Room” to distinguish it from their dad’s mobile “Boardroom”—another comfortable and commodious car, but hardly one that turns heads when she motors across town to a hospital meeting. Their sons shake their heads when they see newspaper references to the “Piper estate.” They have never thought of their home that way. “We had a sense of living a privileged life,” Tad will say much later. “Our parents explicitly said we were blessed in both talents and treasure. But they also made it clear that the gifts we had belonged to the community as much as to us, so we knew we had responsibilities along with the privilege.”

Because they do not flaunt their wealth, and perhaps because they know many families with a greater net worth than theirs, the Pipers assume—or have assumed until recent developments—that the rest of the world is not paying them any attention. Even the occasional news coverage that Bobby attracts downtown has almost always focused on the firm, not on him personally. Unlike many of his peers, Bobby has never enjoyed seeing his name in print. The suicide of the younger of Bobby’s two sisters, in 1962, shocked the family to its core, but the grief and heartache remained a private matter.

Now he and Ginny feel totally exposed to the eyes of the world. Despite their determination, announced during the press conference the day after Ginny’s homecoming, to avoid public comment, reporters want a response to each new report or rumor. Ginny and Bobby see and hear their names in the papers and on the evening news several times a week, often attached to the shorthand identifiers—“socialite” and “tycoon”—that make them cringe.

For the first several weeks afterward, Ginny and Bobby rehash her abduction and the ransom delivery with family members and close friends, but then Bobby stops talking about it, even in private. The Pipers understand and appreciate the FBI’s efforts to solve the case, so they sit down with the agents again and again, ever cordial and willing to help, but they desperately want it all to go away and yearn to return to the comparative anonymity of their former lives.

Bobby still drives to and from the office and takes no special precautions when going to lunch at the Minneapolis Club or visiting a branch office. His firm has not fortified its low-profile, industry-standard security arrangements. If Bobby harbors concerns about certain individuals he has mentioned to the FBI, he keeps them to himself. Son Tad, with whom he works closely, sees no change in the way he operates downtown. Years later, Tad says, “My dad never thought about varying his schedule in anticipation of fooling anybody.”

Ginny does not have the distraction of running a business. She spends most of her days at the first scene of the crime and is surely reminded of the second when she looks at the abrasions on her wrists. Though she isn’t heard to say so, even her beloved terrace and gardens must seem changed in some elemental way, especially when she wanders outside by herself. Bernice and Vernetta, who still come to clean the house every week, must remind her of that earlier Thursday, whether they speak of it or not. The Pipers’ pool has always been available to her daughters-in-law and grandkids, but now Val and Weezer are told to call before coming by to swim. “It wasn’t like before—when you were in the neighborhood, you’d just drop in,” a friend recalls. When Bobby flies to New York, one of the boys is asked to spend the night at the house. Some days her sister Chy has to toss pebbles against the upstairs windows before Ginny will come down to open the door.

Bobby has given Ginny a “panic button” that she keeps close by at home and puts in her purse when she leaves the house. The device places her in electronic contact with a security company if she senses a threat. Bobby has also delisted the home phone number and exchanged their retriever for a foul-tempered German shepherd ironically named Happy, who routinely menaces family members and federal agents when they approach the house. (Another reason drop-ins are discouraged and Chy prefers tossing pebbles to ringing the bell. When Tad and other kin tell Bobby that he will have to choose between them and the dog, Happy is removed and never replaced.) But, though the papers report increased interest in home security systems in west-metro neighborhoods, the Pipers don’t invest in one. Bobby keeps his reasons to himself. Perhaps he believes that lightning won’t strike the same place twice. More likely, according to his sons, he can’t stomach the idea of turning his home into a fortress.

“We simply decided we weren’t going to live in fear,” Tad says later.

But living free of fear will prove easier said than done.

Decades later, Louise recalls the sudden panic that she and Tad experienced when, not long after the kidnapping, they couldn’t find their three-year-old daughter during a game of hide-and-seek. “We were so freaked out,” she says, “just an inch from calling the police.” (The little girl had been frightened by her parents’ cries—their fear fanning hers—and refused to come out of her hiding place.) Louise says she kept exceptionally close tabs on her kids for a long time afterward, reluctant, for instance, to let them set up a lemonade stand at the end of their driveway. The imagined danger, she says, was never far from her mind.

Despite the precautions, Ginny is anxious. There’s reason to believe that Bobby is, too—or that he is operating with a heightened sense of awareness.

This would explain an incident some weeks after the kidnapping when he takes Ginny along to one of his seminary classes in suburban New Brighton and they notice a white Ford Mustang with California plates in their mirror. There are two men in the Mustang, and the Pipers believe the men are following them. Bobby pulls into a Howard Johnson’s. The men in the Mustang follow the Pipers into the lot and park next to their car. The men emerge from their car and go inside the restaurant, where they remain for a few minutes before coming back out and driving away. They say nothing to the Pipers, much less present an overt threat, but Bobby jots down the Mustang’s license number and gives it to the FBI.

Agents track down the Mustang’s registration in California, but the information yields nothing of value. In a subsequent report, an agent notes, “Mr. Piper could not attribute any significance to the incident; however, he and his wife became quite concerned.”

The FBI’s inability to arrest a suspect does not help the family’s sense of well-being. The men who terrorized them are still out there—maybe long gone but maybe not, maybe still a threat of some kind.

By mid-autumn investigators are apparently no closer to making an arrest (or to finding the money) than they were on July 29. To make matters worse, speculation about who kidnapped Ginny and got away with Bobby’s million has become a popular pastime in Twin Cities barbershops, country clubs, and saloons, and the Pipers themselves remain objects of rumor, suspected of not telling the authorities everything they know about the crime.

The FBI’s ambivalence regarding the Pipers’ status as possible suspects is manifest in an exchange of memoranda between Minneapolis and Washington. On October 11, Richard Held writes to Charles Bates, head of the Bureau’s Criminal Investigative Division, requesting authority to give the Pipers lie detector tests.

Mr. and Mrs. Piper have been interviewed numerous times relative to this important case and although there is no evidence indicating either are criminally involved it is felt such an examination is a logical step in attempting to resolve any remote possibility that the Pipers were involved in the kidnaping plot.

A polygraph exam of a victim is “not unusual,” Held points out, “since the victim, for some unknown reason, may withhold information which may not appear to the victim as being pertinent …” The polygraph could, in that event, improve the victim’s concentration, “thereby increasing her total recall.”

Referring to Mr. Piper, the memo continues,

the examination may assist in developing additional information concerning the payoff route noting that he was not in contact with our Agents for approximately three hours after departing on the payoff route. In addition, this examination may produce other suspects who Mr. Piper may not have furnished initially for some unknown reason. It is also believed this examination may be beneficial in insuring cooperation of other family members or members of his business firm.

The memo adds that both Pipers “have indicated a willingness” to submit to an exam.

The next day Minneapolis receives a handwritten note from Acting Director Gray. “What chain of info do we have that indicates ‘any remote possibility that the Pipers were involved in the kidnapping plot’?” Gray asks. “In what other kidnappings have we polygraphed the victim?”

The acting director demands more “meat” before Washington will authorize an exam.

On October 17, Minneapolis responds.

There has not been one shred of evidence or information developed indicating Mr. or Mrs. Piper have been untruthful in this matter or are involved in the kidnaping.

[However,] during the pay-off in this case, at the specific request of Mr. Piper no physical coverage was made and he was not observed [by the FBI or other law enforcement] from the time he departed on the pay-off run until after the pay-off was made … During the exhaustive investigation conducted to date … no [civilian] witness has been identified who observed Mr. Piper during the pay-off run. In addition, Mrs. Piper was held approximately two days in a wooded area infested with insects and did not suffer any bites of any kind. Although Mrs. Piper denied any sexual molestation, it is possible she was subjected to such grossly indignant [sic] acts she would not be willing to admit. Both Mr. and Mrs. Piper suffered extreme mental anguish and emotional strain during this ordeal and it is possible that pertinent information would be developed by use of a polygraph examination which has not come to light … due to possible embarrassment or other reasons.4

As for testing the victims, Minneapolis replies that while the FBI did not administer any exams between 1965 and 1972, four separate kidnapping victims submitted to the tests between 1961 and 1965 “and in each instance deception was noted.” When confronted with the test results, “each admitted the kidnaping was a hoax.”

Again, the local office notes that both Mr. and Mrs. Piper have agreed to take the exam as a “necessary investigative step.”

A few days later, Bureau headquarters authorizes the tests, and on October 27 an administrator from Chicago arrives at the Piper home and, one at a time, hooks up Ginny and Bobby to the jittering machine.

In his subsequent report to the acting director, Held says, “[I]t does not appear the Pipers were involved in the planning of the kidnaping, or that they know who is responsible, or that they were consciously withholding information concerning the kidnaping. There were no responses indicating possible deception.”

On the morning of November 17, two middle-aged men pull up in front of the Piper residence in a late-model Chevrolet Monte Carlo. A few moments later, Ginny emerges from the house. One of the men opens the car’s passenger-side door, and she slides into the backseat. She lies down on the seat, and one of the men places a pillowcase on her head. The Monte Carlo proceeds down the long driveway, takes a right onto Spring Hill Road, and continues in the direction of County Road 6.

The men are Special Agents Arthur Sullivan and Richard Stromme, a couple of Bureau veterans who have been working on PINAP from the beginning. They are taking Ginny to Jay Cooke State Park.

Nearly four months have passed since her last trip to the park. The Piper case is still wide open, with no arrests and few promising leads. Sullivan and Stromme’s assignment is to see if they can determine, by replicating Mrs. Piper’s ride with her abductors, the route the kidnappers followed in July. They hope the ride will stimulate her memory and shake loose some piece of helpful information that has somehow resisted the many hours of interviews she has already endured. The reenactment was the Bureau’s idea, but she is perfectly willing to cooperate.

Once the car reaches Interstate 35, the agents tell her she can sit up and take off the pillowcase. There is no mystery about the middle section of the trip. Nearly two hours later, when they approach the town of Carlton within a few minutes of the park, they ask her to lie down again and put the pillowcase over her head. Please pay close attention to the car’s movement from this point forward, they tell her, and be aware of any turns or grades or sensations indicating road conditions, so you can compare those with what you remember from the first time.

After exiting I-35 at the Carlton exit, they proceed eastward along State Highway 210, crossing a double set of railroad tracks and pausing at a stop sign.

“I remember these,” she says. “I remember this.”

They pass through the village of Thomson, enter the northern edge of Jay Cooke, and drive across a wood-plank bridge. The Monte Carlo’s tires rumble on the bridge’s rustic surface.

Ginny tells the agents that she remembers the sound and sensation of the car driving over the planks.

In the park, the two-lane highway turns right and then descends a steep grade, then requires a series of tight turns as it goes up and down through the uneven terrain, forcing the agents’ car to slow.

Ginny says, “It’s very familiar, this slowing down.”

A few miles later, they turn sharply onto State Highway 23 and continue about a mile south to the power line that traverses the highway. They park nearby and get out of the car.

The agents remove the pillowcase and lead Ginny up the overgrown track through the deserted woods, finding without much trouble the little clearing where she was held. But the woods look different today. It is late autumn in northern Minnesota, and the deciduous trees have shed their leaves. Whatever potential evidence was there when the agents rescued her four months ago is gone now, too. The three of them spend a few minutes at the site, then return through the trees and brush to the car. They eat a late lunch at the Radisson Hotel in Duluth before returning to the Twin Cities. Ginny has nothing substantive to add to what she has already told the agents.

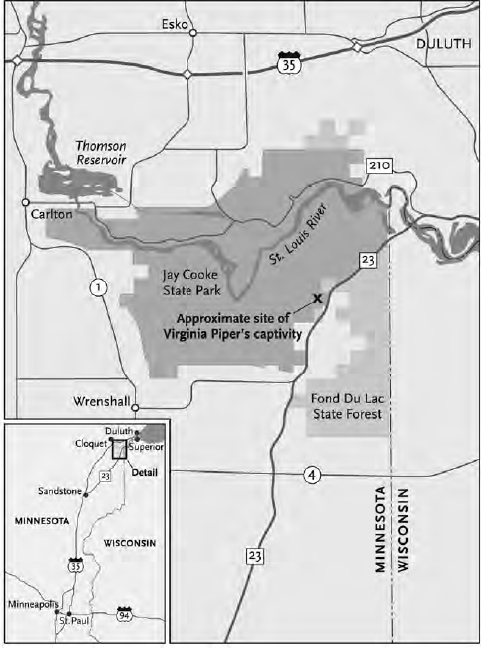

The FBI insisted that the kidnappers drove Ginny east on Minnesota Highway 210, then southwesterly on state Highway 23—crossing a short, unmarked stretch of Wisconsin—to their hiding place in Jay Cooke State Park. If Ginny’s abductors drove instead up Highway 23 to the park site, they would not have crossed the state line and thus would not have committed a federal crime. Matt Kania/Map Hero

Though there are several possible routes the kidnappers could have taken to the park site, Sullivan and Stromme are convinced that the one they took today is the one the kidnappers followed on July 27, based, Sullivan says later, on Ginny’s responses as well as on Sullivan’s belief that this is the logical route if you are in a hurry and trying to minimize notice. It is also the general direction—Highway 23 out of Duluth and Fond du Lac—that the anonymous caller gave Kenneth Hendrickson on July 29.

From the FBI’s point of view, this particular route is also essential because Highway 23 immediately southwest of Fond du Lac crosses the unmarked Minnesota state line and briefly—for only a few hundred yards—passes through the state of Wisconsin, making Ginny’s kidnapping a federal offense.

On November 28, Susan Lange, a teller at the Owatonna State Bank about an hour south of the Twin Cities, has just returned from lunch when a husky “gentleman” wearing a hat and coat asks her to exchange $300 in twenty-dollar bills. “Fives and tens, please,” he says. She changes the bills, the man exits the bank, and Lange clips the twenties together and tucks them into her cash drawer.

“Like ten minutes later,” Lange will recall, the bank receives a phone call saying that “Piper money” has turned up in Owatonna and that everybody should keep their eyes open for a man exchanging twenty-dollar bills. Lange calls over one of the bank’s executives, and they compare the serial numbers of the recent customer’s twenties with the serial numbers in the little book they received from the FBI in August. The serial numbers of the man’s fifteen bills match fifteen serial numbers in the book.

A short time later, Lange describes the man to an FBI agent as a white male, fifty to fifty-five years old, between five-ten and six feet tall, weighing about two hundred pounds, with a ruddy, pock-marked (“rough”) face. She remembers the hat, but can’t recall if the man was wearing glasses. (A coworker says he was.)

The quick transaction in Owatonna—one of several exchanges of “Piper money” in late November 1972—goes down as the first documented appearance of the million-dollar ransom. An individual believed to be the same man Lange served at the Owatonna State Bank has exchanged about $1,600 worth of twenty-dollar bills at three other banks on the same day. Accumulating reports indicate additional twenties have been turned in for other denominations at banks in Rochester, Austin, and three other communities, totaling close to $4,000.

Witness descriptions of the man exchanging the bills are similar enough (a solidly built, square-jawed, middle-aged white man wearing a hat, et cetera) to allow an FBI artist to rough out a sketch, but too general to give the sketch much practical value. The occasional description containing meaningful specifics—a “blue fur hat with a gold band,” “glasses with thick round lenses and gold wire rims,” a “square black or onyx-like ring” on his right pinkie finger, a “blood clot under the nail of his left thumb”—is not corroborated by other witnesses. A report out of Rochester cites a husky middle-aged man in the company of a short woman—the only female of any stature mentioned at this time.

Despite the confusion, Richard Held in the FBI’s Minneapolis office believes this is a major break and floods southern Minnesota with agents. A local sheriff tells a reporter—off the record, of course—that law enforcement is only hours behind the kidnappers. In the Twin Cities a bank-association official reportedly shares the news with a Minneapolis cop who in turn confides in a journalist friend. Aware that the news is on the street, Held begs the media to sit on the story for a few days, in which time his agents will catch up with their man (or men). The media comply until, on November 30, the Minneapolis Star runs the story on its front page, infuriating Held but, in editor Robert King’s words, only “confirming what a lot of people already knew and countless others had heard in the form of rumor and speculation.”

The husky man with a hat and possibly a blood clot under a thumbnail vanishes, visible only in the FBI’s Everyman sketch that the papers include with their follow-up stories.

One of several FBI sketches of Piper kidnapping suspects. This one was based on eyewitness reports following a bearded middle-aged man’s purchases at a north suburban shopping center using twenty-dollar bills from the ransom money. Virginia Piper papers, Minnesota Historical Society

Held isn’t the only one outraged by the coverage. Ginny and Bobby feel betrayed yet again, this time by the Star’s publisher, John Cowles Jr., who lives on the other side of Spring Hill Road and whom the Pipers have always considered a friend.

1 The Monte Carlo was stolen from a Minneapolis car dealership more than two weeks before the kidnapping. Its license plates were stolen from a different car.

2 The thirty-four-year-old wife and mother of four was stabbed and beaten in her home in the comfortable Highland Park neighborhood of St. Paul. Her husband, T. Eugene Thompson, an ambitious criminal attorney, was eventually convicted of hiring her killer, motivated by more than $1.1 million in life insurance and desire for another woman. The case was front-page news in the Twin Cities for the better part of a year.

3 And not only convicted kidnappers or extortionists, but anyone who had connections within the area’s criminal community, including several informants and confidential sources already helping the police or FBI.

4 Three points regarding language: (1) The sinister but broader and less accusatory “persons of interest” would be a more appropriate term than “suspect” in these circumstances, but the phrase would not be widely used by law enforcement and the media until the 1990s. (2) The FBI routinely used the term “polygraph examination.” By any name, the lie-detecting technology was, and is, controversial even within law-enforcement circles, with varying opinions about its probative value. Results of the tests are still not allowed as evidence in American courtrooms. (3) FBI agents and headline writers have never been able to agree on “kidnapping” versus “kidnaping.” Both iterations are correct, but the use of two p’s is generally preferred.