5

CONSIDERING HOW ANXIOUS I WAS ABOUT BISCUIT, it troubles me to realize I didn’t leave for New York until October 2. How could I wait that long? The word that comes to mind is “cavalier.” When I look through my calendar, I’m reminded that I’d already missed a bunch of classes the month before, having taken off on two successive weeks to attend a panel and show Bruno around the house. So maybe I was scared to miss any more. This was my first full-time teaching gig after years on the job market, and I was grateful for it, probably abjectly grateful, in a lank, stooped, Bob Cratchity way. Everything else I’d wanted in life seemed to be slipping out of my grasp, and so I held on to my job as if I’d never heard the warnings about clinging to anything too tightly, though usually those warnings are tendered about things like riches or prestige and not, say, cats. Nobody warns you about clinging too tightly to a cat.

I drove to the airport in my landlords’ car, which they’d thrown in with the house, a terrific deal, if you consider what I was paying. It was a battleship gray Thunderbird dating from the late eighties or early nineties, with a hood as long as a bowling alley. The T-bird was ponderous on turns, and the door was so heavy that it tended to swing back shut before I could get out. By the end of the year, my right leg would be covered with bruises. Still, it would get me down to Myrtle Beach. Once you passed over the bridge, a gray-green steel vertical-lift bridge whose riveted joints rasped beneath the tires, the road was straight and didn’t have too much traffic. The country was flat. Loblolly pines grew on the roadside. There were housing developments and trailer parks and a gentleman’s club that projected a simultaneous air of invitation and supernatural menace, like if I stopped for a quick lap dance, I’d be rolled and have the shit beat out of me and miss my flight and then learn that Biscuit had been run over by a truck while she was trying to cross the road back to the house.

I should add that I’ve never had a lap dance in my life.

Biscuit would follow me when I left the house, but not for very long. Her attention faltered. Something stirred in the weeds on the side of the road, and she’d lunge at it; it might be a vole or a twist tie from yesterday’s trash—one was as good as the other. When we were still living in the village, she could be distracted by any neighbor who happened to be digging in her garden. She’d storm right over to see what was in those holes. Often she was seized by a sudden, furious compulsion to groom herself. The suddenness was almost spasmodic; at times it looked like she was going to tip over. Yet, like all cats, she was also a miracle of poise. Watching her, I marveled at the balletic rigor with which she held up a hind leg, the paw extended so that leg and paw formed the long side of a flawless 45-degree angle, while the rest of her remained heedlessly fixated on her butt. Sometimes I almost thought she might vanish into her butt, or maybe up it—as in that cartoon I loved when I was thirteen, whose caption reads, “Your problem is obvious.”

To me, this tension between abruptness and poise seems an essential part of feline nature. If you accept Descartes’s view of animals as natural automata, machines made of meat and fur, you can visualize a cat as an automaton programmed to shuffle at random among a variety of subroutines. The shuffling can appear jerky and without purpose. Why abandon a nice walk with one’s person to torment a piece of plastic? Why break off investigating the fascinating sounds and smells of a June morning to start fiercely licking one’s back fur? (One possible answer is that domestication has robbed the machine of its original purpose, and it’s simply discharging the energy that once would have been consecrated to hunting and killing.) At the same time, individual routines have to be carried out perfectly: the hind leg angled just so during grooming, the toes fanned apart so that you can see the smooth, eraser-pink clefts between them; the forepaws tucked beneath the breast before resting; the prey seized and reprieved so many times before it can finally be dispatched.

In general, Biscuit had a shorter attention span than Bitey did and a milder disposition. Bitey was the cat who’d skulk all day outside poor Tina’s door, rehearsing the woe she had in store for her, whereas I once saw Biscuit sitting amicably beside a field mouse in front of a bed of daffodils in the garden. They couldn’t have been more than a foot apart. Even if cats have terrible depth of visual field, she must have been aware of the creature, and it of her, but they ignored each other like commuters on the subway gazing up with tender neutrality at the zitty, love-starved foreigners in the ads for Dr. Zizmor’s dermatology practice. At length the mouse seemed to realize what it was sitting next to and began sidling toward the flower bed. Only then did Biscuit take notice of it or remember that it belonged to the category “prey.” The fur on the back of her neck rose. Her whole being quivered with interest. In another moment she would have pounced on it, if I hadn’t picked her up and carried her, squirming and hissing, into the barn. She was really pissed at me.

If someone asked me why I love Biscuit, I might cite her mildness, even though it may not have been mildness at all, judging by the many tiny corpses deposited on the porch, just forgetfulness. But I also loved Bitey, and there was nothing mild about her. Soon after F. and I moved in together, Bitey put her in the hospital. I was in the kitchen when I heard snarls at the foot of the stairs. Tina had gone down there, and my cat had cornered her in the front vestibule and was rearing above her in a gloating rage. I started at them, yelling. F. came out of her room and ran downstairs to break up the fight. I remember feeling tacitly reproached. The stairs were steep and covered in unctuous brown carpeting. As I watched from below, F.’s feet slid out from under her, she grabbed hold of the banister but continued to fall or slide, and her arm twisted grotesquely in its socket and went limp. She cried out. I raced up to her, shooing cats out of my way. F. was lying on her back. She was conscious but her face was white and shiny with sweat. She thought the arm was dislocated. I told her to lie still while I called 911, but she said she wanted to go to the bathroom; she was scared she was going to be sick. Cautiously, I half-carried her upstairs. I must have made a call then, though I have no memory of it, because a pair of EMTs showed up within minutes. Ambulances come quickly in the country, as long as it’s not a weekend night when drunken teens roar up and down the roads looking for trees to wrap themselves around. The stretcher was too wide to fit through the bathroom door horizontally, so F. had to be strapped to it and carried out at an angle. I walked beside it as the EMTs trundled her to the ambulance, holding her good hand. If Bitey had been anywhere in sight, I would have leapt on her and shaken her like a rag, but all the noise must have scared her into hiding, and I didn’t see her again till one or two in the morning, when I brought F. back from the hospital, her arm having popped back into its socket without any help from the admitting doctor, who sent her home with nothing but a crummy blue sling that was shortly covered in cat hair. Bitey was lying on the dining table on top of a heap of mail, and she barely glanced up when I called her an evil shit.

Of course cats have no sense of good and evil. I doubt dogs do either, but we’re more inclined to think of them as moral creatures, or at least as ones susceptible to moral suasion, properly backed up with a rolled-up newspaper. “Bad dog!” you yell, and the dog hangs its head and looks at you the way a Gnostic believed its ancestor looked at God on the day we provoked him to invent death. The jury’s out as to whether that look signifies remorse or fear. “Bad cat!” accomplishes nothing, unless you really yell it, in which case the subject runs for cover. None of your expiatory displays of guilt or shame, it just books. Biscuit was in some ways a very human cat, by which I mean a cat who responds to human cues, answering your call at least some of the time and giving you a look of what seems like gratitude when you fill her saucer with milk, though maybe it’s really approval; you’ve figured out what she wanted from you. But I never saw her express anything that remotely resembled guilt. Like Bitey before her, she learned not to claw the stereo speakers or start knocking things off the dresser early in the morning, but her forbearance appeared to be entirely pragmatic, and at those times she forgot herself and stretched sensuously toward a speaker with outspread talons and I snapped, “Biscuit!” she paused and looked at me. Somebody else might have called her expression insouciant or defiant or even, because of how her whiskers bristled, belligerent, but to me it was just blank. I’d pressed the “Biscuit!” button, which made her come, but she was already here, and the tone was the tone of “no,” the button that made her stop. So what did I want?

It may be their inability to display remorse—really, their inability to comprehend what remorse might be—that caused cats so much trouble in the Middle Ages. Probably their stealth and night walking didn’t help either. People thought of them as the devil’s creatures and persecuted them accordingly. Those jolly, howling orgies of cat killing may in fact have been autos-da-fé, though knowing human nature, it’s more likely the mobs just wanted an excuse to visit suffering on something small and weak. At the same time they were torturing and burning cats, Europeans were also torturing and burning heretics, especially the Cathars of the Languedoc. (One imagines an English-accented voiceover on the History Channel: “Is it mere coincidence that ‘Cathar’ contains the word ‘cat’?” Well, actually, yes, according to my dictionary, which traces “Cathar” to the Greek katharoi, “the pure ones.”) The violence against Cathars was organized and genocidal and bore the imprimatur of a couple popes, who proclaimed the campaign against the heretics in Toulouse as much a crusade as the ones against the infidels in the Holy Land. By the mid-fourteenth century, some 500,000 Cathars had been slaughtered, along with an undetermined number of Catholics who had the misfortune to live in Cathar towns. (Asked how to tell one from the other, a commander of the crusaders said, “Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius”—“Kill them all. God will recognize his own”—originating a slogan that seven hundred years later would be silk-screened on T-shirts you could buy at the county fair, usually with a skull in a black beret nearby. In the same bins, you could find shirts illustrated with a picture of a naked and seemingly headless man, though his head, on closer inspection, was wedged between his buttocks. The caption said, “Your problem is obvious.” Wilfredo was the right age to appreciate these shirts, but the last time we took him to our county fair, he was only interested in the stuffed animals they were giving as prizes at the sharpshooting booth.) There’s no telling how many cats were killed during this period—enough, according to some commentators, that in parts of Europe their numbers were greatly suppressed. In the absence of their natural predator, rats flourished, and when the Black Death arrived in 1347, inundating Christendom with sweat, pus, and black blood, it may in part have been because there were so many rats around to spread it. Some 100 million people died wretchedly. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius.

A footnote: before it decided to exterminate the Cathars, the church tried to convert them. It delegated the task to one Diego de Guzman, whom it later canonized as St. Dominic. The order he founded, the Dominicans, became known as the “dogs of God” (domini + cani) for the enthusiasm with which its members sniffed out heresy. Once they’d wiped out the Cathars, they shifted their operations to Protestants and crypto-Jews.

On the night Bitey dislocated F.’s arm, I sat beside her on one of the emergency room’s brittle bucket seats, filling out the admissions forms for her because she couldn’t use her right hand. How pale she was in that diagnostic light! I could see every vein in her eyelids. I had to keep asking her questions; I didn’t know her medical history, let alone her insurance provider, and shock made her vague and slow to anwer. I could remember snapping at my mother in similar circumstances as a teenager (“What do you mean you don’t know what medicines you’re taking?”) and was relieved I’d become at least a little more patient since then. Maybe it was because I knew that on some level the accident was my fault. In Texas, your neighbors can sue you if you let your cattle stray onto their land, and I imagine the damages are higher if somebody dislocates an arm because of it.

Much of the anger I used to feel back when I was checking my mother into the hospital (for pleurisy, for pneumonia, for hepatitis, for herniated disks, for a spot on the lung that might be cancer but wasn’t, though twenty-odd years later it would be) had been anger at being attached to her, yoked to her, with her, the last being the way you identify yourself as a teenager. At least I did when I was one.

“Are you with her?” pronounced “huh.”

“No, man, I’m not with huh. I’m with Fran.”

“He’s with Carol and those Walden kids.”

“She’s with those heads who hang out by the fountain.” That need to place yourself in a context, with a girlfriend or boyfriend, ideally, but failing that with a group or clique or, that word of wincing recollection, a tribe. Our egos were still unfinished—in places they were only dotted lines—and so we needed to borrow parts of each other’s. But after spending an afternoon and evening, sometimes even a whole weekend, hanging out with my tribe, smoking hash and snorting crushed-up Dexamyl with the children of shrinks and advertising executives in an apartment overlooking Central Park, I went home to the apartment where I lived with my mother, and then I was with huh. In the hospital, it was worse. Our affiliation would be evident to anyone who might be passing through the waiting room. One of the few questions I didn’t have to ask her was the names of her emergency contacts: the first was my grandfather; the second was me.

And now I was with F. I was happy to be with her, even proud, though, really, what else could I have done: waved bye-bye as the EMTs slid her into their ambulance, then gone inside to make myself a late-night sandwich? I felt a small pang of disappointment when for emergency contact, she asked me to put down her mother. It wasn’t until we got married two years later that she started putting me down instead. From a logical standpoint, there’s no reason why I should have cared so much, beyond being the first, rather than the second, person to learn that something bad had happened to her or having the privilege of bringing F.’s medications and makeup to her in the hospital, along with the boxy terrycloth robe she likes to wear, the one with a picture of a sitting cat on the back. Still, it mattered to me. I wanted my name on her forms.

About a year before this, F. had taken me to the hospital. I’d developed a persistent headache, and although I’ve had so many headaches in the course of my life that I’ve become a connoisseur of them, the way people are of cheeses, this was a kind I’d never had before. It was localized on the right side of my head, and the pain seemed to originate in a spot on the surface, as if I’d been rapped there with a hammer. It hurt for days; Advil did nothing for it. And one night, as we were leaving a movie, F. asked me what was wrong, and I said wonderingly, “It’s still there,” and she asked me if I wanted to go to the hospital. I said no. Then I said maybe. Then we were in the emergency room of St. Vincent’s. Ten years before, this had been the charnel house of New York. Every day, dozens came here to die, not all at once but a few lurching steps at a time. They had boiling fevers, faces mottled with cancer, diseases that before this had been seen only in birds. The doctors hauled them back, stabilized them, and sent them home, but a few weeks later they returned, sicker. After a while, they died.

By the time I finally saw a doctor, I was starting to doubt that I was in as much pain as I’d thought I was. I was also bored and embarrassed at having dragged my girlfriend to a hospital on a Saturday night instead of a nice restaurant. We were in a yawning chamber sectioned like an orange by flimsy curtains, through which we glimpsed dim shapes of suffering humans attended by other humans dressed in white, green, and powder blue. My doctor was a young Israeli woman with lovely breasts that proclaimed their splendor beneath her open lab coat. It was all I could do not to stare at them as she bent over me. Later F. told me how funny I’d looked, following the beam of my caregiver’s pencil light until my gaze intersected her boobs, at which point it froze raptly and then swerved. Maybe the doctor saw this too. I remember thinking she looked very amused considering she was examining somebody who might be having an aneurism.

She left for a while, cautioning me not to move too much. Throughout the examination, I’d been distantly aware of a continual sound, soft, feeble, monotonous as the hiss of a respirator. Only now did I recognize it as moaning. It was coming from the examining area to our right. The voice was a man’s. “Help me, doctor,” it kept saying. “It hurts, it hurts bad.” It was awful, the awfulness coming from the voice’s mechanical character and from the rupture between the mechanical and the human—the animal—truth of pain. Every animal understands pain, but as far as I know, no one has yet built a machine that does. “What’s wrong with that guy?” I asked F. Because she was sitting rather than lying down, she could see him. “I don’t know, he looks like he might be mentally ill.” The moment she said it, I knew she was right. “Help me, doctor,” the voice said again. F. and I looked at each other.

I don’t remember either of us saying anything—maybe we squeezed hands—but we both turned our attention to the droning sufferer behind the curtain. We—how do I put this?—we willed him better. No, we understood that our wills weren’t that powerful. We sent him kindly thoughts. My kindly thought was, “You’re okay, friend, you’re okay.” I don’t know exactly what F.’s was. When I think back to that night, I’m not sure how I knew we were thinking the same thing at the same time. Maybe I didn’t know in the moment and just extrapolated from what she told me later. That’s one of the epistemological problems of a long relationship. You’re never sure what you actually know and what you reconstruct from your partner’s reports after the fact. I’m not crazy about the word “partner”; it suggests the work of marriage but not the pleasure. But it’s true that people in a relationship are partners in recording its history, like two scholars who join efforts to write a chronicle of a small, unimportant town where something out of the ordinary once happened. In a successful relationship, the partners’ accounts more or less tally. They may differ in detail, but the overall narrative is consistent, and so is the tone. But then there are histories where nothing matches, so that in adjoining sentences the townspeople are good Catholics and devout Cathars, living harmoniously and in gnashing enmity. But we used to be so happy. I was never happy. Never.

On the other side of the curtain, the voice underwent a change. It still sounded mechanical, but the machine was slowing. In time it would stop. It said, “Thank you, doctor. Thank you.” Disregarding instructions, I sat up and peered through the curtain. Silhouetted behind it I saw a slouching, shirtless man with a soft, matronly stomach. F. and I grinned at each other. A moment later we started laughing. Laughing worsened the pain in my head, but it seemed worth it.

A while afterward, the Israeli doctor came back and told me that what I had was a stress headache. “It’s very common,” she reassured me. “Especially in men your age.” Mildly, I reminded her that I’d never had a headache like this before. It was bad enough having a doctor with breasts see me as middle-aged; I didn’t want her seeing me as middle-aged and hypochondriacal. She shrugged. “Maybe you never had stress before.”

Cats are supposed to be solitary creatures, but when you live with multiples of them, you become aware of their social interactions. These are less boisterous than those of dogs, which usually involve running and panting, tails wagging and tongues flying like flags. What goes on among cats is more complex and mercurial, with small, unexpected shifts of power and moments when hostility abruptly gives way to solidarity, or vice versa. At mealtimes, each is conscious of what the others are getting. Biscuit would often look up from her bowl to glance at the cat nearest her, then give it a cuff—not a hard cuff but hard enough to make it back away—at which point she’d move over and help herself to its shreds or pellets or, my favorite stroke of the marketing people at Friskies, “classic paté,” which appeals at the same time to snobbery and squeamishness. She didn’t seem to mind if the loser changed places with her. She might have forgotten that the protein it was eating had once been hers. Or maybe she didn’t care; it was just sloppy seconds. Considering the feline reputation for independence, their values are surprisingly conformist: a cat wants what other cats want. It wants it because they want it. It wants other cats to want what it has. F. once gave Suki a piece of cheese and noticed that instead of polishing it off right away, the crabby gray tabby held it between her paws until she saw Tina enter the room. Only then did she begin eating her prize in tearing mouthfuls, pausing from time to time to look intently at the other cat.

The gaze is important to them; they want to see and be seen. Biscuit was drawn to houses that had cats living in them and showed a preference for ones where the cats were kept indoors. There was one where she’d loiter for hours, clambering onto one of the downstairs windows (she was never a very good jumper) so she could peer inside and, I’m pretty sure, display herself to the inmates. Sitting broadside on the sill, she’d lick her paws in a way that put me in mind of someone buffing her nails. Behold, she might have been saying, here is a free creature who goes where she pleases and helps herself to the bounty of lawn and hedgerow!

They want you to look at them, too, but not too long, since that might indicate you’re thinking of eating them. I no longer remember who first taught me that if you blink slowly at a cat two or three times, the cat will blink back, the same as it would at another of its kind. You’re supposedly assuring it that you mean it no harm. Of course, I’d observed this for years among friends’ cats without knowing its significance. It was just an example of their minimal style of relating. Once I learned what blinking meant, I couldn’t resist practicing it with Bitey. I must have spent hours blinking at her as we sat across from each other in my living room in Baltimore or, later, in apartments in New York, the sounds of the river of worldly glamor lapping through the windows. I’d look at her from the sofa. There she sat with her forepaws together and her tail coiled around them, her chin slightly tucked. I blinked and waited, blinked again. I was listening to Marvin Gaye or Robyn Hitchcock, love raw as the mark of an axe in a half-felled tree or sheathed in irony, though, really, what’s so ironic about “I feel beautiful because you love me,” except maybe the marimbas? Again I blinked. Bitey blinked back. It never ceased to make me happy.

Although cats are the most popular pet in the United States, there are way more dog books than cat books—not just guides to their care and training but narratives, both fictional and true. Stories of heroic dogs, mischievous dogs, incorrigible dogs, loyal dogs, loveable dogs, life-transforming dogs. It’s easier to write about a dog than a cat. With dogs, there’s always something going on. They race to greet you at the door; they jump up and plant their paws on your chest; they muzzle your crotch; they bring you things they want you to throw to them or to try to pull from their mouths. They bark at you: all you have to do is say, “Speak!” They look at you with eyes brimming with meaning, and the wonderful thing about that meaning is you don’t have to interpret it; it’s obvious. Maybe it’s the thousands of years they spent hunting beside us, learning to read us, learning to make themselves readable. A dog is a dictionary without definitions, just words that mean nothing but themselves. Feed me! Play with me! Walk me! Love me! The object of these sentences is “me,” but their unvoiced subject is always “you.” Whose knee are they pawing if not yours? At whose feet have they dropped that frisbee, tooth-marked and sopping? Into whose eyes are they gazing? With dogs, it’s all about you. No wonder they’re easy to write about.

A cat may look at you, too, it’s true, but it will look just as fixedly at a wall. No other creature displays such free-floating intentness. How to distinguish between the gaze that says something and the gaze that says nothing at all? If nobody had ever told me what a cat’s blinking means, would I have figured it out on my own? The pleasure of dog ownership is having an animal that speaks your language, or a language that shares many terms with yours, like Swedish and Norwegian. A cat doesn’t speak your language. But when I blinked at Bitey and she blinked back, I briefly had the illusion that I could speak hers.

The South Carolina border was marked by signs for a nearby fireworks emporium. Fireworks were legal in South Carolina, along with every type of firearm, including AK-47s and twelve-gauge tactical personal-defense shotguns designed for the homeowner who needed to drive off a bloodthirsty mob. Folks in North Carolina didn’t know what they were missing. They might, though, if they lived close enough to the state line. The signs were that big. As I approached, I had another moment of temptation in which I wondered how many cherry bombs I could get for twenty bucks and whether they’d let me take them on the plane as long as I checked my bag. The temptation passed quickly. It wasn’t that strong to begin with. Given a choice between fireworks and a lap dance, I’d rather have a lap dance. I stopped at a light and, looking up, saw the head of an immense black cat snarling at me from the roadside with a mouth wide as the gate of hell. Its nose and tongue glowed as if red hot.

My God, who would want that as a pet?

F. had men before she met me, some of whom she saw for a year or more, some of whom she loved. But she’s spent most of her adult life alone. I think I have never met anyone more lonely. Her solitude, along with her quiet and general eccentricity, has caused her social awkwardness. For a long time she didn’t drive, and she didn’t own a car until we bought one together; even in the country, she got around by walking and, because of that, was viewed with pity, condescension, and occasional unease. She was an affront to people’s sense of categories. Walking was an activity of the poor and the health-conscious elderly, and F. was youthful and well dressed. Sales clerks don’t know what to do with her. She doesn’t get small talk and when strangers try to make it with her, she looks at them with a clinical bafflement that’s easy to mistake for disdain. One of the first things she told me about herself was that she was often insulted at parties. At first I doubted her—why would anybody do that?—but as I started going to parties with her, I saw that it was true. Maybe it wasn’t actual insults, but people slighted her, seemingly for no reason. She assured me it happened less when I was with her. It was one of the things she liked about being together.

It’s true that I’m more socially adroit than she is, more comfortable with the insincerities that ease open the stubborn cupboard drawers of small-town life. The Friday evenings at the restaurant whose bartender used to rake leaves off your front lawn when he was a little kid. The New Year’s Eve party held in the dreary strip mall near the entrance to the highway—not even a strip mall but a cluster of unfrequented small businesses anchored by a diner that’s had four or five different managements in the time you’ve lived here—one of whose storefronts now turns out to contain a dance club. Who knew, a dance club barely a quarter of a mile from the fencing-and-gazebo barn? In the semidarkness, middle-aged revelers perform the jogging steps of the middle-aged alongside teenage girls in shiny, skimpy dresses and their boyfriends. A bass grunts. Some people are wearing domino masks, which conjures up an image of the orgy in Eyes Wide Shut. And like that movie’s protagonist, who sees the familiar skin of the world peeled back to reveal its secret sensual anatomy, you realize that these partygoers are people you know. The man in the snappy black-and-white tuxedo shirt lifts weights beside you at the gym. The woman in the sequined pantsuit owns the dry cleaner’s. Her husband always calls you by F.’s last name. What you’re supposed to do is give the bartender a good tip and ask him how his mom is. You’re supposed to tease the orgiast from the gym: “So this is why you been doing all those flies? You wanted to look good for your New Year’s date?” F. wouldn’t do that; it wouldn’t occur to her to.

After we got married, my actual presence at such events became less necessary, since she now wore a wedding band. “People notice that,” she’d say, flashing the ring, “and I can see the relief on their faces. They know how to place me.” She still says it, even now that what we are to each other is uncertain. There are women who find a wedding band demeaning, since it essentially serves as an emblem of possession, a function that was more evident when only women wore them. The ring signifies that the wearer belongs to a certain man and can’t be taken from him without consequence. In that sense, it’s also a warning device, like a car alarm. It’s unclear whether the warning is directed at other men or at the woman herself. But, along the same demeaning lines, you could also compare a wedding band to a pet’s ID tag; typically, dogs get a bone-shaped one and cats a silent little bell. Such tags also express ownership and, indeed, often proclaim it, being engraved with the name and phone number of the pet’s owner. But their purpose isn’t to prevent theft so much as to help find the pet if it gets lost. Pets get lost all the time. Drawn by an interesting smell—in cartoons it’s typically portrayed as a vaporous hand with a beckoning finger—they slip their leash or wander out of their yard and soon find themselves on a street they don’t recognize, gazing up at the legs of oblivious hurrying strangers. Sometimes they roam farther still, beyond the places where people are. A landscape of rustling underbrush and yellow eyes glinting in the shadows of the trees. A dark wood in which there is no straight path.

There’s no archaeological record of when men and women began to marry. Given that some form of marriage exists among nomadic peoples like the Tuareg, Kham, and Warrungu, it’s likely that humans were marrying before they had much in the way of property. So much for Engels’s view of marriage as a bourgeois institution. Say in the beginning its chief purpose was the protection and rearing of small children and the formation of alliances among people who might otherwise be enemies. That rangy fellow with the dead eye and the necklace of dog’s teeth wasn’t so menacing when you discovered he was the husband of your wife’s sister, and you were grateful to be able to call on him when other nomads tried to drive you away from the watering hole. Marriage extended kinship beyond biology, connected you to people who didn’t share your blood. In all the early accounts of marriage, the idea of connection is paramount. When God gives Adam a mate, it’s not in the interest of his sexual fulfillment. It’s because it is not good that the man should be alone.

This period of companionship lasted only a little while. Perhaps it ended with the Fall. Having seen each other turned inside out like flayed skins, could the man and the woman stand to look at each other again? Could they stand to be looked at? In Masaccio’s painting, they walk side by side but don’t touch. Both of them are encysted in their shame, and one wouldn’t be surprised to learn that once they had wandered a distance out of Eden and begotten their unhappy sons, they parted ways and had nothing more to do with each other. It established a pattern. Men labored with men and went off to war with them; they feasted and got drunk together and sang the kinds of songs men have been singing since they discovered that they sounded better when they were drinking. The women served them, first the food, then the bowls of wine or beer. There was no pretense of fairness. Afterward, they went off by themselves and ate and drank the women’s portion and sang songs of their own. At a certain hour of the night, the men and women lay down together. Things went on in this manner, with variations, for the next 10,000 years.

Societies that observe this arrangement are described as homosocial, with men and women inhabiting separate spheres that only narrowly coincide.

In some times and places, the sexes dined together.

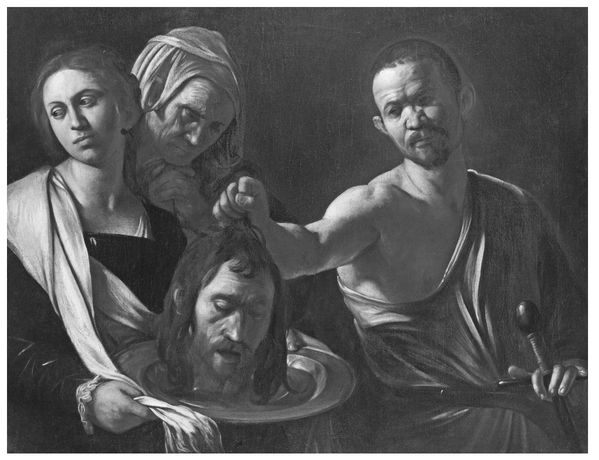

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (London, c. 1607), National Gallery, London. Courtesy of Art Resource.

Sometimes they came together for worship or to attend public entertainments.

But for much of history, the chief area of coincidence was marriage, especially the marriage ceremony, in which a man and woman stood together before their families, under the eye of that God who decreed it wasn’t good for man to be alone. From then on, they were one, or at least they were treated as one by their society, that one being, implicitly, male. The paradox was that once the man and the woman had publicly sealed their union, they largely returned to their separate social realms. One can visualize marriage as a smaller version of the compound giant pictured on the original frontispiece of Hobbes’s Leviathan.

Abraham Bosse, frontispiece of the first edition of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651). Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

Instead of being made up of thousands of men, the leviathan of marriage contains a single man and woman. The face it wears in public is a male face; it resembles the husband’s face, but it has just one unvarying expression, sober, contented, a little dull. The leviathan appears in public only on rare, mostly ceremonial occasions. The rest of the time, it breaks up into its constituent male and female homunculi, and these spend much of their time with others of their kind. Or this was the practice until well into the last century.

However, even when engaged in her own pursuits, the woman is now identified as belonging to—as being of—the leviathan or, for all practical purposes, her husband. It’s as if instead of wearing a ring, she were carrying a little mask (I imagine it as being made of gold) with her husband’s face on it, and on certain occasions she must hold the face in front of hers and speak from behind it, as if in keeping with Genesis 20:16: “Behold, he is to thee a covering of the eyes.” Depending on the husband’s status, this can be advantageous. Witness the courtesies accorded the wives of the baron, the mayor, and the pastor in former times, the wives of celebrities and corporate CEOs today. The prie-dieu embroidered with the family coronet. The personal shopping assistant at Barney’s. Of course, it’s oppressive for a woman to have to go through the world pretending to be her husband, but the masquerade doesn’t just carry privilege: it carries protection. In a man’s world, an unmarried woman is up for grabs. She may be raped. She may be robbed. She may be tortured and murdered, even burned alive before crowds that one variously imagines as raucous or dumbstruck by the spectacle of suffering unfolding before them. This was what was done to witches. (Some witches, of course, were married women. In a man’s world, finally, any woman is up for grabs, and a husband’s protection is about the same as that provided by a fig leaf.)

There were no great witch hunts in Europe until late in the fourteenth century. During what is called the Dark Ages, the church denounced the belief in witchcraft as superstition, and in AD 794 the Council of Frankfurt made the burning of witches punishable by death. I wonder whether the resurgence of the practice owed anything to the extinction of the Cathar heresy a hundred years before. I don’t mean a Halliburton-like conspiracy on the part of the Inquisition, which, having done away with the Cathars, needed another threat to justify its continued operations. By 1480, it already had Protestants for that. But people like to believe in the hidden enemy, the worm in the fruit. Protestants weren’t hidden; they nailed proclamations to cathedral doors. The Cathars were hidden, at least some of the time. And what could be more hidden than the woman who lives in your village, maybe even next door to you, distinguished from her sisters only by the fact that she is alone, with no man to vouch for her? For company, she may keep an animal, which is actually a disguised demon. At their esbats or sabbats, witches were said to fornicate with goats, but in the popular imagination, as enshrined in the Halloween displays at Target and CVS, the witch’s familiar is usually a cat, a black one.

I think back to the way cats clean their dirty parts, I mean, hunching forward while holding a leg up in the air, presumably to give them fuller access to the area in need of cleaning. What distinguished Biscuit’s approach to hygiene, as I said, is the combination of precision and abandon, the geometric line of the suspended leg and the shapeless slouch of the rest of her, which created the impression—at least it did in me—of a creature burrowing into herself as if trying to disappear, so intent on disappearing that she’d forgotten about one part of herself, her raised hind leg. And it’s this hind leg that I imagine remaining poised in the air after the rest of Biscuit made her impossible exit, like the needle of an invisible compass quivering toward an invisible north.

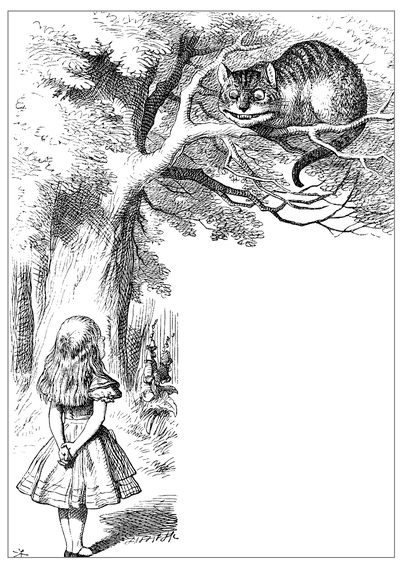

Of course, Biscuit wouldn’t be the first cat to vanish and leave a part of itself behind. Lewis Carroll’s grinning Cheshire Cat vanishes repeatedly, at first with such abruptness that Alice complains it makes her dizzy.

Sir John Tenniel, “The Cheshire Cat,” illustration from the first edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

“‘All right,’ said the Cat, and this time,” Carroll tells us, “it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone.”

Carroll may have been inspired by a Cheshire cheese that was made in a mold shaped like a smiling cat. The cheese was cut from the tail end, which would make the grinning head the last part to be eaten. But it’s also true that beings seldom vanish all at once. Mostly they do it slowly, almost imperceptibly, until one day you look at the space they occupied and see it’s empty. Or almost empty, since it’s also the case that most beings leave some trace of themselves behind. A smile lingering above the branch of a tree. The scent on a blouse. A leg pointing at nothing.

We went to events in the city, of course, especially in our early years together, when I still had the loft, and these were more comfortable for F. because she knew most of the people at them. Some of them were her friends, and others were fellow travelers in the worlds she moved through, the worlds of readings and art openings and awards dinners where the small, exquisite portions usually went half eaten, not because the food was bad but because people were too excited or too anxious or worried about spilling something on the Armani or being photographed with their mouths gaping to admit a forkful of some other thing, I don’t know what, duck confit. I used to take great pleasure in imitating what someone might look like in such a photo, my head tilted to one side, my eyes popping with greed, my teeth—which were still very bad back then, back before the dental work I’ll be paying off for the rest of my life—bared. It always made F. laugh. In fairness to her, she may have been the first of us to do the imitation.

F. didn’t like all the people she knew at these events; really, she disliked many of them, much more than I did. Well, she knew them. And she understood what drove them, the slow- or quick-fused ambition, the desire for money or fame or beauty and glamour, beauty and glamour especially, always paired, as if one couldn’t exist without the other. F. also wanted those things. “If only I had legs like hers,” she’d sigh, gazing with forlorn admiration at a woman across the room. “My whole life would’ve been different.” But she made no effort to disguise her appetite; she’d tell a stranger about it. She hated the people who pretended to have no appetite and viewed any display of hunger with pitying amusement, even as they peered over your shoulder to see what you had on your plate.

To me, beauty and glamour seemed so unattainable that I could only respond to them with cowed sullenness. F. sensed my discomfort long before I told her about it, which in the beginning I couldn’t, and for a long time she’d stay close to me when we went to events where beauty and glamour were likely to be present. The way she did it didn’t feel protective so much as proprietary. I was hers, and she wanted to be seen with me. I was always grateful for this. I liked it even better if she went off to talk with somebody she knew for a while, leaving me free to wander around the room or stand in a corner, hoping that I looked mysterious rather than just awkward as I surveyed the space’s other occupants. Few of them, to be honest, were truly beautiful or glamorous, except for the occasional fashion model slipping past like a gazelle that had been imported into a barnyard in the mistaken belief that it could be mated with the livestock. I guess what I liked about F.’s absences was the evidence that she trusted me not to fall apart or try to mount one of the gazelles or get in a fight with a strange bull while she was gone. And I loved to watch her making her way back across the room toward me. When she spotted me, I could see the questing look in her eyes give way to pleasure; I was what she’d been looking for. Sometimes, though, she’d manage to sneak up behind me and grab me around the waist. She’s proud of her stealth, and she got a kick out of the little start I gave, though the truth is I often started on purpose.

“Behold, he is to thee a covering of the eyes.” The speaker is King Abimelech of Gerar. He’s addressing Sarah, the wife of Abraham. Many commentators believe he’s scolding her, though, really, if he should be scolding anybody, it’s Abraham, who passed off Sarah as his sister, under which misimpression Abimelech “took her” (Gen. 20:2) as his wife. “Took”: the word is, to put it mildly, vexing. The Hebrew laqach is defined as “to take (in the widest applications),” which could include rape or the sort of nuptial kidnapping that was still being practiced symbolically by the lusty groomsmen of France at the close of the Middle Ages. This is one of two times in Genesis that Abraham pretends he and Sarah aren’t married. On both occasions, he’s afraid that some powerful figure—before Abimelech, it was the pharaoh of Egypt—will covet his ninety-year-old wife and have him killed in order to possess her. The subterfuge saves his skin, but at the cost of her chastity, or the near cost, depending on how you read “took.” Abimelech insists he never laid a finger on Sarah. Or, at least, that’s what he says when God appears to him in a dream and tells him he’s a dead man for taking liberties with her, and even if he’s lying, you can hardly blame him. I mean, who knew?

Most biblical commentaries put forth the view that “a covering of the eyes” refers to the veil that was worn by married women in the ancient Middle East and is still worn there today, and not just by married women. The phrase is syntactically ambiguous. Whose eyes are being covered, the veiled woman’s or the lustful viewer’s? In either case, the purpose of the veil is the same, and when Abimelech tells Sarah, “He is to thee a covering of the eyes,” he’s defining a husband’s responsibility to his wife: to be her veil, the protector of her modesty. Not because that modesty is important to him (it doesn’t seem to be important to Abraham), but because it may matter to her. That the patriarchy values something doesn’t mean that women may not value it too, for reasons that have nothing to do with men’s claims on their bodies. Masaccio’s Eve shields her breasts and sex without any prompting from Adam, who, locked behind the visor of his grief, may not even notice that she’s naked. The patriarchs are often held up as models of marital conduct—this is especially so in fundamentalist Christian circles—but Adam seems awfully wishy-washy, and Abraham is even worse. The slights and betrayals. The fling with his wife’s handmaid, who flashes her pregnant belly like a big piece of bling—Look what your husband gave me—until the wife gets fed up and makes him cast her out into the desert, and the kid with her. The spineless way he hands Sarah off to any big shot who looks at her twice. Jews aren’t supposed to do that. Eskimos are supposed to do that.

We think of modesty mostly in sexual terms, as a reaction—even an anticipatory reaction—to sexual excitement, an attempt to rein in its lunging surge. Eve covers her sexual parts, not her face. That Adam covers his face might support Freud’s belief that women are intrinsically more modest than men, but it also suggests that modesty can be construed more broadly. There is a modesty of the body and a modesty of the soul. Both can be outraged. And there is a social modesty that deters some people from calling attention to where they come from or who their parents were or how much money they have and causes other people to lie about those things; in the latter case, one speaks not of modesty but of shame. Beyond shielding his wife from the gaze and touch of other men, the husband’s task may be to help her navigate in social space, for it’s there that she is most likely to be shamed. The social realm is where shame lives.

Once, early on in our marriage, I met F. for dinner at a restaurant with our friend Scott. I was late, and when I got there, they were already eating and a second man was sitting across from Scott, in the seat next to mine. I knew him, but not to speak to. He was an old guy who had once done something on Broadway; it made him one of our town’s celebrities. Arthur had a wide, loose-lipped mouth framed by the ponderous jowls of a cartoon bulldog. You could imagine them wobbling in outrage or exertion or, less often, from laughter. I had a sense of him as someone who was used to watching impassively as other people laughed at his jokes but would under no circumstances laugh at anybody else’s. Laughter was tribute, and he refused to pay it. Sitting diagonally across from him, F. looked particularly delicate, an impression heightened by the way she cut her food into small, precise bites that she placed in her mouth one by one with small flourishes of her fork while she held up the other hand before her like a paw. I don’t know why she eats this way, but to me it’s part of her charm.

I remember the drift of the conversation. F. was talking about her appetite, which is robust for somebody her size and used to be even more so. When she was younger, she likes to brag, she could put away a plate of fries and follow it with a milkshake and a piece of pie and never put on a pound. Maybe that’s what she said that evening. “That doesn’t surprise me,” Arthur said. It sounded like the windup to a joke, but in the next moment, his voice darkened. “I don’t doubt you’d eat anything.” The darkness was the darkness of contempt, of loathing. F. stared at him. Somebody else might have said, “Excuse me?” which would have given Arthur the opening to pretend he’d been joking. But F.’s quicker than that, and what she said back was quick and biting. It may have been, “I guess you’d know”; that would have been appropriate. She didn’t raise her voice, but her anger was unmistakable. Looking back, I think Arthur had counted on her to be too startled to defend herself. Maybe he was drunk; he had a reputation as a drunk. He told F., “I can just imagine the kinds of garbage you put in your mouth.”

Inanely, I turned to look at him. He was leaning back in his chair. His jowls were inflamed. He might have been resting after a bout of gluttony. Scott called for the check. We tossed down bills and credit cards as if our money had become hateful to us and avoided each other’s eyes while we waited for our change. Arthur heaved himself back from the table and made for the men’s room. “Who is that pig?” F. asked me. Her eyes were bright with hatred. “Why didn’t you say something?”

If I reconstruct the incident, which probably lasted no more than three minutes from start to finish, less than a short pop song in the days of AM radio, it took me several seconds to realize that the loathsome old hack had been insulting F. The rest of the time, I’d been floundering for a response. If Arthur had been younger, I might just have said, “Watch it, buddy!” which isn’t clever but gets a point across, but he was old, and I was raised to defer to old people. I said none of this to F. I knew better than to excuse myself. I only said I was sorry and for months afterward imagined an alternate version of the evening in which I grabbed Arthur’s wine glass and flung its contents in his face.

I got my revenge a few years later, at another restaurant, where I was eating with Scott and his girlfriend. Arthur came up to our table on his way out. In the moment I saw him, my face was suffused with a terrible heat, not the heat of a blush but the heat that assails you when you open the door of a furnace. I half believed you could see it burning across the room. But Arthur seemed not to notice. He spoke with my friends, then turned to me with an outstretched hand. He’d lost weight since I’d last seen him, and this, together with a certain vagueness to his gaze, created an impression of diminishment. I looked at him steadily but kept my hand at my side. Then I looked away. It might have been satisfying if I hadn’t heard that in the time since that wretched dinner he’d had a stroke. He may not have recognized me; he may not have remembered insulting F. That whole portion of his memory may have been torn from his mind like a sheet of paper from a notebook and crumpled into a ball and tossed, coincidentally, into the garbage, which, in any event, is what it had become.

F.’s recollection of the original fight—or say the ambush, since neither she nor I could be said to have fought back—is different from mine. After we parted ways with Scott and got into the car, she says I turned to her and snapped, “I really didn’t appreciate you embarrassing me in front of my friend.”

During the hour-and-a-half drive from the college town to the airport, I passed through the following localities:

Belville

Bolivia

Supply

Shallotte (pronounced Shal-lot)

Carolina Shores, skipping a side trip to nearby Calabash

Little River

Myrtle Beach

If I hadn’t been in a hurry, I might’ve stopped in Wampee.

On reflection, my explanation for why I waited till October 2 feels like bullshit to me. I have to wonder whether the sleepless nights, the hysterical phone calls and e-mails (by now I’d deputed at least two of my friends to come by the house and call my cat at different times), weren’t just a front, a lot of thrashing, hand-wringing activity thrown up to disguise a vacuum. Maybe I was just lazy. Maybe I didn’t love my cat, or didn’t love her as much as I thought. I mean, it’s hard enough to know when you love a person.

In one of his later lectures, Jacques Derrida poses the question of why, if he walks naked into the bathroom and his cat follows him inside and looks at him, as a cat will, he feels ashamed. Derrida sees this shame as a measure of the boundary, which is to some extent an arbitrary one, drawn up by bribed surveyors, between the human and the animal. He connects his shame to the shame our ancestors felt when they ate the forbidden fruit and realized for the first time that they were naked. In this scenario, Derrida’s cat may stand in for God; its gaze stands in for the Creator’s gaze, being similarly unblinking and inscrutable. Really, all Western representations of God are deficient inasmuch as they give God the eyes of a human being rather than those of a cat.

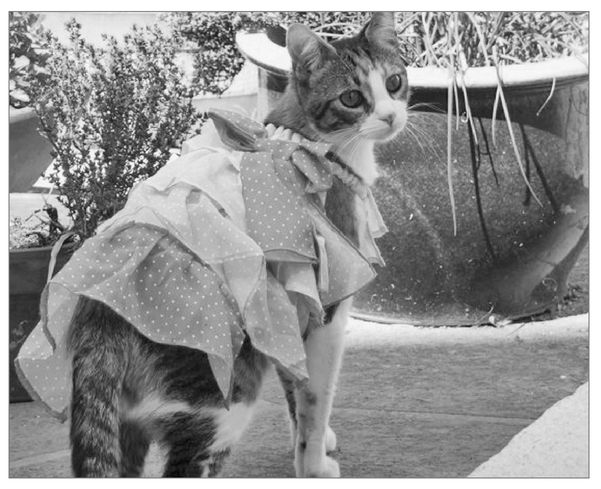

Is nakedness a condition unique to humans? Is naked something only a human can be? In French, a synonym for naked is à poil, “down to the hair,” the hair being that of a beast. A naked human, then, is a human stripped down to a bestial state, in which it is cold and fearful and ashamed. In contrast, an animal that has its hair has everything it needs, and most attempts at improving its condition only cause it discomfort. Witness the evident discomfort of a cat dressed in human clothing.

The cat pictured above might be called an image of offended modesty.

Right after the man and woman ate the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, they began acting strangely, and the dog and cat in the garden watched them with perplexity. They were the same creatures they had been a moment before, mangy, sparse coated, moving clumsily about on their hind legs. But something about them was different. They shivered and cast anxious looks about them. They drew together but shrank from each other’s touch. Strangest of all, they plucked leaves from the tree and tried to cover themselves with them. Why were they doing that? Today we have forgotten the moment when our forebears first knew they were naked and were ashamed. But the cat and the dog remember, and that is why they look at us so intently, wondering what changed us.