6

JUST PAST LITTLE RIVER, I HAD TO TAKE A TURNOFF onto Route 9 and then merge onto Highway 31 South toward Myrtle Beach. The sign for the turnoff was smaller than the ones I was used to up north; I could easily have missed it. The ramp jogged gently—to my mind, sneakily—to the right, then swung back and climbed so that I found myself arcing over the continuation of the road I had just been on and an unpicturesque wetland where dead-looking trees rose out of brown water. No wonder the bastards were so mad to develop here. Who wanted to see that shit on the way to the beach? The traffic I’d been congratulating myself on missing was suddenly thick about me, blades of late sun glancing off its hoods and grilles. How clean those cars were.

A few years before I’d been in a town in Florida where people drove their pickups on the beach, not twenty feet from the breaking surf, truck after truck in a slow, martial procession whose brutish throat-clearing drowned out the sound of waves. I was working with a famous monologist who was in the middle of a breakdown. A bunch of us had taken him to the beach as therapy, but when he got out of the car and saw those trucks, he staggered back in fear. A moment later he glanced upward and dropped into a crouch, shielding his face with his hands. He choked out a cry. “Shark!” And following his gaze, I saw that there really was a shark overhead, a great, swooping shark-shaped kite whose grinning mouth stretched to devour the world, and us with it. Two years later, the monologist killed himself by jumping off a ferryboat into the freezing water of New York Harbor.

Now, caught in traffic on an overpass above another beach, I thought about poor Biscuit. I worried that she must be afraid in her exile, far from home, assailed by strange sounds and smells: the trembling hoot of night owls, the bloodthirsty mirth of coyotes closing in on their prey, the acrid scat of animals that feed on other animals. At the time, I thought nothing could be more terrible than such fear. Only looking back do I understand that whatever Biscuit encountered in the wild, it would be something that on some level she already knew, that she recognized by instinct. The wild was where she’d been born, after all, or at least found, and she’d had no way of knowing that the dogs baying up at her were people’s house pets. Nothing she encountered in the woods near our home would be as strange to her as the sight of trucks driving along the edge of the ocean or a Mylar shark wheeling and flapping in the sky. She might fear for her life, but she wouldn’t fear she was going mad. I doubt a cat has even the remotest sense of what that might mean. And I can’t imagine the circumstances under which Biscuit would dive into an endless expanse of dull gray water, water cold enough to stop the heart, wanting it to be stopped. Only a human would do that.

On those mornings when I came into the bathroom naked and Biscuit looked up at me from the radiator, where she’d settled sometime after slipping off the bed during the night, I don’t think that what I felt was shame. I don’t think I was even especially conscious of being naked. I might become conscious of it on those occasions when I petted my cat, which she seemed to have invited me to do by rolling over and stretching, displaying her luxuriously soft (and, because of where she’d been lying, luxuriously warm) stomach, and she seized my hand and began to lick it while lightly raking it with her extended claws. (I’m pretty sure she wasn’t doing this to hurt me but to keep my hand from getting away.) At that moment I’d be suddenly aware of the temptation my genitals might present to a creature programmed by instinct to strike at dangling objects, and I’d retract my groin as far as I could while letting her go on grooming my unresisting hand. To me, this is not shame; it’s awareness of my vulnerability, though maybe what I’m really talking about is fear. Maybe when Derrida speaks of shame he really means fear. Maybe he was ashamed to admit he was afraid of his cat.

What might Biscuit have made of my nakedness? She must have recognized it as being different from the state in which she usually saw me, covered in soft, warm fabrics that were so pleasant to sit on—she especially sought out my lap when I was wearing my flannel bathrobe—and that bore my scent along with the odors of coffee, garlic and olive oil, tea tree oil chewing sticks, motor oil and grass cuttings, laundry detergent, and household cleaners. She knew most of those smells from the house and its environs, and when she detected them on me, she must have had an idea of where I’d been and what I’d been doing: preparing the bitter black water I drank every morning, with a shameful waste of the rich, sweet milk that ought to go in her dish; pushing the growling thing that chewed up the grass in strips; going out to fetch the paper bags from which I took the things F. and I ate and then left out for her to climb into so that no one could see her. Sometimes I’d come into the house smelling of things that had no counterpart in her experience: the subway, on days I’d been working in the city. What would she make of that, a canned stew of humans shrieking through the darkness beneath the earth? Some other cat might think it was a kind of pound, a pound for humans. But Biscuit had never been in a pound.

And what went on in her mind when she watched me undress, before I took a shower, for instance? To undress is to cross the threshold from clothed to naked, and judging by the intentness with which she studied me, the procedure interested her. Did she see my discarded clothing as a foreign layer that I’d managed to slough off, as she might manage to disentangle herself from one of the shopping bags she nested in? Or did she see it as part of me, like a skin or, really, like fur, which was part of her but could also be shed: if only it weren’t shed so easily! Sometimes when we kept Biscuit from going out, she’d get so frustrated she’d sit by the door and pull out her fur in mouthfuls, seizing up thatch after thatch of it with irate twists of her head. It looked agonizing. Coming back home was like walking into a barbershop, all this tawny hair strewn on the floor where she’d been sitting, like the pattern of iron filings that shows where a magnet was.

I understand that I’m ascribing to my cat the most human of human behaviors, the ascription of meaning. I’m imagining that the tilt of her head, the fixity of her gaze when she looked at me, signaled curiosity, or a particular disinterested variety of curiosity that might be called speculation. But can a cat speculate? Nobody questions that they’re curious, but most evidence suggests that this curiosity is basically utilitarian, that when a cat stares at something, or sniffs it, or nudges it with a paw, climbs onto it or inside it, it’s trying to fit the object of its curiosity into one of a limited number of conceptual slots, like the slots in an accordion file. Is this thing dangerous? That is, does it belong to the category of threats that may include other animals and, for some cats, human beings except for their owners (sometimes the owners too), along with moving cars, lawn mowers, and vacuum cleaners? Is this something I can eat? Is it something I can stalk and kill? Is it a female I can mount? (This asked by males.) Can I play with it? Is it something I can climb or hide in? The previously mentioned study of Kaspar Hauser cats indicates that some of these slots are present at birth, waiting to be filled by things their isolate, light-deprived owners may not even guess at.

Humans, too, have mental slots in which they file experience, and some humans have very few of them. We’ve all known people who view phenomena solely in terms of whether they can be eaten, screwed, or watched on a screen. But humans also possess another kind of curiosity for which the filing metaphor is inadequate, unless you picture an accordion file that contains an infinite number of slots, some of which are bottomless. And it’s with this kind of curiosity that I imagine Biscuit watching me in the bathroom, wondering why I pull off my pelt and why that pelt changes from day to day, from rough to smooth or from slick to hairy, why sometimes it has a row of small hard nipples protruding from it, from which no milk comes, and why at other times the nipples are replaced by a sort of seam or scar that comes open with a soft, purring rasp.

But who am I kidding? When she looked at me, Biscuit probably saw the same thing the cat in the famous Kliban cartoon sees when it looks at a wall, as indicated by the thought bubble above its head: a wall.

In her case, it was a wall that moved and gave her food and love, though she might not know what love is. And I doubt it entered her mind that the wall told itself she loved it, too, educing as evidence the way she licked its hand in the morning and greeted it with an almost birdlike chirp when it came home from wherever it is a wall goes.

F. thinks that love is a specifically human emotion. She doesn’t mean that only humans are capable of love but that only humans are really suited for it, and that when a domestic animal—a dog or a cat or one of the intelligent talking birds—learns to love, as it may from prolonged contact with a human being, it is almost always to its detriment. Sometimes that love is fatal to it.

Not long after we became involved, I had to go away to South-east Asia for several weeks. The whole time I was gone, I missed F. as if she were the one who’d left and I were moping in the same dingy coffee shops I’d been moping in before I met her, for years. Nothing I saw overseas was exotic to me, not the rice paddies or the Buddhist temples shaped like enormous bells with young monks sitting on their steps in their orange robes, not the markets selling jackfruit big as fourth graders, not the crumpled shell of an American helicopter or the range where you could fire M-16s and AK-47s, depending on which set of combatants you felt like role-playing. It was just a landscape of subtraction. I came back diminished by a tropical infestation that wrung my guts like a washcloth. F. met me in my loft. She said I looked thin. We spent the day and evening in bed. Later we went to dinner. Because I was too weak to walk far, we chose a restaurant only a few blocks away. I don’t know if it was sickness or love that made it so hard for me to eat. I’d raise my fork and watch it idle before my mouth. What was a fork for? This question wouldn’t have occurred to a cat.

F. too appeared to be in rapture. She smiled across the table with shining eyes. But as I watched, a change came over her face; it seemed to melt and then re-form. Her smile became a smile of hatred, as cruel as that of an empress sitting in an arena and gazing down at men who were about to be slaughtered for her.

“Why are you looking at me that way?” I tried to keep the fear out of my voice, but a moment later I heard myself plead, “Don’t look at me that way. I don’t like it.” I’m no longer sure of how she answered me. Maybe she said, “I wonder if you’re really what you seem,” or “I hope you don’t turn out to be weak.” She may have said, “I can’t help myself. When I feel this way too long, I just want to bite.” One thing I’m sure of is that she didn’t pretend not to know what I was talking about. Between us lay the reality of that condemning smile. Both of us acknowledged it, though she may not have known the reason for it any more than I did.

At the time, I thought the smile meant she’d fallen out of love with me and hated me for it. I understood that feeling. The night D. proclaimed she loved me more than air, I cringed inwardly the way some people cringe from a street beggar, and a while later I was angry at her, the way people are at beggars. Why doesn’t somebody do something about them? Years before, I’d felt the same anger at my girlfriend T., watching the meek curve of her shoulders as she sat before the TV in the apartment we shared in penury. I’m not sure if I was angry at her for tricking me into loving her or for letting me see her as she was, a bright, modestly pretty woman content with the modest pleasure of watching TV on a week night in a shitty apartment with a bathtub in the kitchen and burlap stapled to its rotten plaster walls. Falling out of love was so terrible that it had to be somebody else’s fault. Why should F. be any different?

The Spanish verb querer means both “to love” and “to want.” Yo quiero may be the beginning of a cry of sexual longing or of an order at the butcher counter. The same duality occurs in other languages, just not as blatantly. It defines love as a condition of insufficiency, a lack that can be cured only by the recovery of a missing object. Love is lovesickness. The lover is an open wound calling to the knife. In the Symposium, Plato has Aristophanes speak of that primeval race of compound beings—barrel shaped, eight limbed, with a face on either side of their spherical heads—whom the gods split in two “like a sorb-apple which is halved for pickling, or as you might divide an egg with a hair,” so that forever after their cloven descendants wander the earth like ghosts, mourning what was taken from them: “Each of us when separated, having one side only, like a flat fish, is but the indenture of a man,” Plato writes. What a terrible phrase that is, “the indenture of a man,” a man bitten down to a stub. How can you not hate someone who reminds you of your indenturedness, especially when he is sitting across from you, close enough for you to see the tooth marks? Who made those marks?

On the day we were to begin living together, we found ourselves circling the Bronx in a fourteen-foot rental truck, searching for an alternate route to our new home after a cop herded us off the approach to the Taconic and told us the parkway is closed to commercial vehicles. Who knew our truck was a commercial vehicle? It wasn’t like we were doing this to make money. Aghast at what we’d have to pay in the city, we’d decided to rent a house in the small town where F. lived. The truck was cavernous, or had been before we’d packed it. Now it was stuffed with stuff, mostly towers of crated books. My old roommate said the books were intellectual trophies and advised me to just take pictures of them and hang them on the walls of the new place, the way humane hunters pin up photos of the lions they didn’t kill. He said it would make the move a lot easier. Of course, F. muttered afterward, he didn’t lift a finger to help us. We bumped and swayed alongside the river, whose steely glint on our left reassured us we were heading north. Then, suddenly we were crossing it. On a bridge! How had that happened? The bridge spilled us out in another state. “Where are we?” I asked F., but she couldn’t read the map. She still can’t read them. I knew we were supposed to be back on the other side of the river, but it was another half hour before I could turn around. And it was another two before we got to our new home, a two-story Dutch colonial covered in red aluminum siding that made it look like a toy caboose. Perched on its modest lawn, it seemed scarcely bigger than the truck we were about to offload into it.

We carried things inside, two small people, already middle-aged. The dining table wouldn’t fit through the front door, and I couldn’t find the screw gun I needed to take the top off the trestle base, so we left it on the lawn, figuring you could do that in the country but not realizing that when you do, you get a reputation as trailer trash. By the time we got to F.’s house, the light was fading. She had fewer things than I did, but many of them were still unpacked. Clocks, pictures, sofa cushions went into the truck piecemeal. On seeing us approach with her carrier, Tina began racing wildly about the apartment, almost panting in fear. When we finally scooped her inside and locked the gate behind her, she bashed against it till her nose bled. “Oh God!” F. cried. It was the most upset she got that day. If she was inclined to blame me—I was the one who locked the gate—she was grateful to me for getting rid of the decaying mole corpse she found in her pantry, where the little orange cat must have brought it in sometime before. It was my first experience with something far gone into putrefaction. I had to light a cigarette before I could bear to pick up the twist of blackened, half-liquefied matter with a paper towel. Having done this, I felt like a man. Which makes me wonder if there’s something intrinsically manly about disposing of rotting corpses, even very small corpses, or if it’s just about being able to do something that a woman can’t or won’t. Of course another woman might have disposed of those corpses perfectly well, even without a cigarette. But I’m not sure I could have fallen in love with her, or she with me.

We were still carrying F.’s things into the truck when it began to rain; the sound on the roof was deafening. For a while we huddled in the back, watching it smash down. It grew late, and we finished the move figuratively on tiptoes, like reverse burglars. Then we collapsed half-clothed onto a bed. In the morning we looked out the window and saw that the big maple on the front lawn had gathered all the red in the world into its foliage. It would be our tree. Its leaves would whisper to us as we slept or made love or read to each other in bed, and every fall we would rake them off the lawn and stuff them into big black trash bags. The only peace Ching would know in his haunted old age would be lying in front of it, staring at nothing. If only we could have buried his ashes there. But the ground was hard.

Looking down, I saw that the dining table was lying where we’d left it beside the door, its maple top spangled with rain.

For poor Tina, as I said, the house turned out to be a place of torment. From the moment she first picked up her scent, Bitey never missed an opportunity to put the fear of Cat into her. (I can only imagine what Tina felt when she saw the black beast send her human skidding down the stairs, seemingly just by looking at her.) There were moments when I thought F. would tell me that it was either her or Bitey. I don’t know what I would have done then. You can give up a young cat for adoption, but who was going to adopt a middle-aged one that looked like Richard III and liked to bite the hand that petted her?

And the thing is, I loved her. I loved her as much as I would if I didn’t have a girlfriend. I don’t understand how that happened. In the beginning, I was alone and she was new, not just a new creature but a new phenomenon in my life, like a star that appears in a quadrant of the sky where no stars shone before. I’d grown up in a house without animals. My parents were European refugees, and like many Jews of their time and origin, they saw animals as dirty and a little scary: I’m not just talking about dogs, which it makes sense to be scared of if you come from a place where they were used to herd terrified humans into abattoirs, but, in my mother’s case, cats. If one entered a room where she was sitting, she’d stiffen and grow pale. The cats I had when I was young were just ideas, probably inspired by a memory of a bleating pop song that used “two cats in the yard” as a metonymy of bohemian domestic bliss.

At first Bitey was an idea too: a companion animal, quieter than a dog and less demanding, requiring little more than food and water in her bowl and fresh litter in her box. But having nothing much better to do in those days, I spent a lot of time looking at her, and she became real. And because she was an animal, graced with an animal’s self-absorption, she didn’t mind my watching. She stretched as if I weren’t there watching her. She stalked shadows and dust bunnies as if the world contained nothing but shadows, dust, and herself. She stared at walls. She hunkered in the cave of her being with slitted eyes, her forepaws tucked beneath her, her tail draped around her like an empress’s stole, perfectly indifferent to the weight of my gaze. Love begins with looking, Proust tells us. I looked.

Bitey also went missing in September, late in the month, and I was terrified that she’d been snatched by a backwoods Satanist who was going to sacrifice her for Halloween. I don’t know if we had real Satanists where we lived, but we had surly, thick-witted teenagers in Slipknot T-shirts who’d tell themselves they were Satanists as a pretext for setting an innocent house cat on fire, the same way earlier generations of surly thick-wits had told themselves they were Christians. How many miles I rode my bike in search of her, summoning her with the racket of IAMS “Adult Original with Chicken.” “Bitey!” I called over and over. How many times in years to come F. and I would go about crying cats’ names in loud, forlorn voices. People pretended not to stare at us from their porches, and we pretended not to see them staring.

A few weeks after we got her back, Bitey developed a sudden, terrible thirst. All night long she lapped from her bowl, frenetic and pop-eyed, then stumbled away like a drunk. When I took her to the vet the next morning, he thought it was diabetes. In the course of the day, the diagnosis kept changing. She had diabetes, but somehow it involved her liver. Then it wasn’t diabetes. It might be cancer, but an X-ray showed no tumors. That evening F. and I came to see her and found her lying on her side on a steel table, emaciated—it had only been a day!—her eyes glazed. It was the first time I ever cried in front of F. She held me. Once I’d imagined that having someone to hold you when you were sad would be one of the benefits of marriage. But in the moment, it only felt embarrassing, and it didn’t take away the fact that my cat was dying.

Actually, she wasn’t dying, but it would be another week and $3,000 before I knew that. No one could ever say definitively what she’d had, what she still had when she came home with us, only that treating it involved feedings of a revolting prescription cat food that had to be blended with water into a grayish-brown slurry and then squirted into Bitey’s mouth with a syringe, plus daily doses of a feline-strength formulary of the enzyme SAME, popular in Europe as an antidepressant, and daily administrations of subcutaneous fluids and antibiotics. The treatment was supposed to take a couple months. F. was away on a job, and I worried that I wouldn’t be able to do it all myself. But Bitey was still weak and docile. All I had to do was sit down beside her on the bed, pet her a little to get her in the mood, then reach for the bag of fluid I’d hung from a ceiling hook, put a clean point on the line, and slip the point into the loose skin at her scruff. The worst part was the little pop of the incoming needle. I think it was that, rather than pain (cats don’t have a lot of nerves back there), that sometimes made her start. For the next five minutes, I’d sit with her, scratching her ears as I watched a hundred milliliters of fluid drip from the bag and travel under her skin in a mouse-sized bulge before it was absorbed. About halfway through the procedure, I’d inject the antibiotic into a Y-port in the line. How astonishing that a doctor—even an animal doctor—had sold me a box of twenty-gauge syringes and that I was using those syringes on my cat and not myself. Bitey took it stoically. Only toward the end would she start growling. “Almost done,” I’d tell her and give her a treat to keep her quiet a while longer.

Did she understand that this was for her own good? As long as we’re talking about the threshold between human and animal, we might consider that humans are the only beings that seem to recognize that some kinds of painful and degrading treatment—injections, catheterizations, Hickman lines, CAT scans and MRIs, the shaving of head and pubic hair, enemas, colonoscopies, the splitting of thorax or abdomen and the plucking out of internal organs, which sometimes are not put back—that these ordeals, which any sentient creature might be expected to fly from howling, are beneficial to them. That the stickers and splitters have friendly intentions.

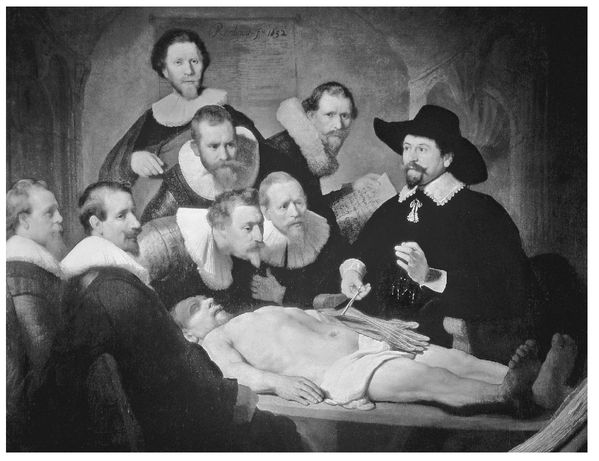

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), Mauritshuis Museum, Amsterdam. Courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library.

Children have to be taught this; it can take years. And even grown-ups sometimes forget. A friend of mine, coming to after a surgical procedure, began clawing at the lines in his hands, wanting to know why he was being tortured. Later he said he must have gone out of his mind for a while. But you might as well say he’d momentarily come into his right one. In his delirium, he’d broken free of the decades of indoctrination that teach us to accept pain and humiliation as long as they’re inflicted by strangers in lab coats.

F.’s father had also broken free of his indoctrination; I don’t know that it did him any good. He hadn’t been to a doctor since one had diagnosed him with chronic leukemia years before. He didn’t speak of people going to the hospital; he spoke of them going to the slaughterhouse. “The bastards tell you they’re taking you to the slaughterhouse for some tests, and that’s the last anybody hears of you.”

We visited him the Christmas before we were married. He and F.’s mother had divorced late, and he still hadn’t gotten over it. The dark condo with its brown carpeting unraveling like a laddered stocking. The yellowing cards of Christmases past arrayed on shelves and coffee table. The cheap cookware that had never held anything but canned soup. They were the marks of someone who either couldn’t live by himself or had chosen not to, preferring to stage the last years of his life as a reproach: to his faithless wife, to the children who didn’t visit him enough, to an entire world that knew nothing of his grief. The resemblance between father and daughter was eerie, down to the domed forehead and rabbit-like twitch of the nose. F. had done her best to create a festive atmosphere. She’d gone to the shopping center and come back with a spiral-cut ham whose slices fanned open like the pages of a book. “Isn’t it nice, Daddy?” She presented him with a heaped plate that he barely glanced at. “I suppose.” He said the ham wasn’t as good as it used to be.

In former years, F.’s father had been prone to rages in which he’d rail at his wife and shove the children around. The threats he’d made sounded preposterous to me, but they must have been frightening and deeply embarrassing to three naive adolescent girls staring mutely as a red-faced grown-up told them that Castro was going to march in and shove his cigar up their asses. Now there was no trace of the old ferocity. His voice never rose above a murmur. Still, as we were talking in the kitchen, the refrigerator let out a squeal, probably something wrong with the fan, and abruptly the old man bared his teeth—bared them like an animal—and slammed it with the flat of his hand. “Bastard!” His eyes met mine for a moment, then looked away.

A few months after this, he fell ill. Probably he had been ill all that time but had refused to admit it. He couldn’t eat, and he hurt everywhere. F. went down to Lexington to help care for him but, after a week, felt she had to go back to work. No sooner had her plane landed than she was suddenly struck by the certainty he was about to die. In a panic, she flew back once more and got there in time to sit by his bedside with her sisters as the last bit of life was twisted out of him.

During the time F.’s father was dying, I was sometimes petty with her. She was away, and I wanted her with me. She was sad and withdrawn, and I wanted her to be cheerful. Even now the memory of my behavior shames me. It also puzzles me. My mother had died only five years earlier, and for a long time afterward I’d walked through the world in a dream and bristled at any claim other people made on my attention; you’d think I would have understood what F. was going through. I’ve been told this amnesia isn’t unique, and I can only relate it to the amnesia that comes over women after they give birth. The only way to bear this thing is to forget it. Of course, a woman who’s had children can always choose not to have any more. But when it comes to death, you can’t push away your plate and say, “No thanks, I couldn’t eat another bite.” The death kitchen goes on serving.

We put off our wedding six months. Late that spring we went back to Kentucky to clean out the old man’s house. Before we left, we held a small memorial. I don’t remember if F. bought another ham; it would have been fitting. But there was nice food, and wine and flowers, and we covered the dingy furniture with sheets, which produced an effect that was both austere and ethereal. Not many people came, apart from the family. At the climax of the afternoon, F. put on a tape we’d made of music he’d liked: a cut of a Scots marching band whose shrilling pipes lifted the hair on the back of your neck; the theme song of the old TV show The Avengers; some big band jazz he would have listened to as a young man on a last leave before shipping out for Italy, where most of his unit was wiped out at Anzio. From that same period, there was “I’ll Be Seeing You,” sung by Jo Stafford. Stafford’s version may be the saddest song in the American songbook, saturated with yearning, slow as a dirge. Why does she sing it so slowly, you wonder? But, of course, “I’ll Be Seeing You” is a song of the war years, and it’s clear that Stafford is singing to a man who won’t be coming back. She knows it, and he knows it. She’s singing a love song for the dead. This accounts for the omnipresence of its object. The singer sees him everywhere—the children’s carousel, the chestnut tree, the wishing well. Nothing like that happens when you just break up with somebody. In your imagination, she is where you know her to be: going out with an asshole she met at El Teddy’s. Only the dead can be everywhere, and that’s because they are nowhere.

I made the tape hastily, without EQ, so some tracks were much louder than others. Somehow I managed to lose several seconds of “Nessun Dorma.” I hate to think what F.’s father would have said about that, but none of the guests seemed to really notice. F. and I may have been the only people there who were listening to the music as music rather than as the background for a gathering that couldn’t decide whether it was sacred or social. F. said that her father would also have listened to the music as music and gotten angry with anyone who tried to talk over it. His remarks would have been restricted to a running commentary on the soundtrack: “‘Nessun Dorma.’ ‘No one shall sleep.’ From Puccini’s immortal Turandot.” But over time the commentary would have become increasingly emotional, until he was pacing the living room in agitation and, eventually, in rage.

The guests stole out until it was just F., her sisters, and me. The tape continued to play. The final track was a song F.’s father was unlikely to have listened to, Iggy Pop’s snarling cover of “Real Wild Child.” But F. had asked me to put it on the tape, feeling it expressed some aspect of his personality. Maybe it was the part of him that had bared his teeth in the kitchen, though I would have said that was just a passing convulsion of rage. You could imagine Iggy baring his teeth as he sang, but baring them the way you do when you’re biting into a steak, a nice, thick, bloody one, the blood running down his chin. F. got up to dance, and I joined her. She’s a terrific dancer, lithe and sexy and peppy and funny. One moment she’d be rolling her hips like a girl in a cage and the next she’d be prancing about on tiptoe, and she inspired me to be almost as uninhibited. It didn’t occur to me that it might be inappropriate to dance at a memorial, especially the memorial of someone who, if he’d lived a few months longer, would have been my father-in-law. In former times, the Nyakyusa or Ngombe people of Tanzania were said to do this as a matter of practice, and their funerals, according to the anthropologist Monica Wilson, were correspondingly jolly:

Dancing is led by young men dressed in special costumes of ankle bells and cloth skirts, often holding spears and leaping wildly about. Women do not dance, but some young women move about among the dancing youths, calling the war cry and swinging their hips in a rhythmic fashion. . . . The noise and excitement grow and there are no signs of grief. Yet when Wilson asked the onlookers to explain the scene, they always replied, “They are mourning the dead.”

Turandot is Puccini’s last opera. He died before he could finish it, and it was given its present ending by a second composer. When the opera was first performed at La Scala, on April 25, 1926, the orchestra fell silent in the middle of the third act, and the conductor Arturo Toscanini is said to have laid down his baton and addressed the audience: “Qui finisce l’opera las-ciata incompiuta dal Maestro, perchè a questo punto il Maestro è morte” (“Here ends the opera left incomplete by the Maestro, because at this point the Maestro died”). The curtain fell.

F. and I almost postponed our wedding a second time, since a few days before it was supposed to take place a pair of hijacked jetliners crashed into the World Trade Center. After a day or two of indecision—during which we fretted about how petty it was to even be thinking about a wedding when almost 3,000 of our neighbors had just been murdered before our eyes—we were persuaded to go ahead: our friends who lived in the city said they needed us to go ahead. As one of them put it, “I need a party to go to.” If I’d had any real doubts, I might have been swayed by the stories of the people who jumped from the burning towers holding hands. I don’t know if any of them were married to each other; some of them may have been lovers, as often happens in workplaces. For months and years, they’d kept their relation secret, but in a matter of minutes the need for secrecy was over, and they jumped together, in full view of the world, holding hands. A man and a woman leaping off a burning building while holding hands struck me as a metaphor for marriage, the clause in the vow that goes “till death shall us part.” But this probably says something about my laziness and the shortness of my attention span. It took only ten seconds for the people who jumped from the World Trade Center to hit the ground, and that’s not a long time to hold hands.

I could tell I was nearing the airport when I began to pass beachfront lined with condos that leaned contemptuously over the undeveloped real estate of the Atlantic. What must the tenants who lived to seaward feel when they stepped out onto their balconies? Satisfaction at their unobstructed view of white sand and blue-green water or irritation that they had to share it with their neighbors or, worse, the tiny freeloaders strolling down the public beach with zinc oxide on their noses? Across the highway were golf courses and an amusement park full of corkscrewing waterslides and a Medieval Times restaurant. Curious about what a medieval menu would look like—larks’ tongues? chine of beef?—I later checked out the online reviews. One visitor said the dungeon had been a letdown.

I parked and walked to the terminal. It was almost sunset but still warm. The passengers at the ticket counter wore shorts and sandals and were tanned various reddish browns. I’m sure I was too; I tan easily. If I ran into people I knew when I got up north, they’d exclaim at how good I looked. Up there, it would already be getting cold, and some mornings there’d be frost on the ground. If I were still living at home, I’d be harvesting the late vegetables. Biscuit liked to watch me do that. On seeing me head for the yard with a spade and hand rake, she’d follow me closely, which used to puzzle me until I realized she was probably waiting to see if I’d dig up any small rodents. You see what a clever cat she was. She’d sniff the roots I tugged from the ground, plump and matted with earth. But she always turned away. They were only beets, and what could be less interesting to a cat than a dirty beet?

Bitey was never the same after her illness. She still enjoyed menacing Tina but could no longer do it with her old élan. After one assault, F. lost patience with her and, seizing her by the back of the neck, dragged her the length of the kitchen, meaning to lock her in the basement as punishment. She knew better than to try picking her up, but there was a time when she wouldn’t even have been able to scruff her. Bitey screamed in protest, her limbs splayed impotently on the tiled floor. Probably compounding her wretchedness was the fact that Suki was following her closely and sniffing her butt, and Tina, her intended victim, was watching with interest. A humiliated cat probably emits a special tincture of shame that its fellows find deeply pleasurable.

Some months later, while I was petting her, she bit my hand with more than usual ferocity. She wouldn’t release me. She just glowered up at me with those absinthe-colored eyes; it really hurt. At last I gave her a swat, and she sprang away. But one of her fangs remained lodged in the meat between my thumb and forefinger. It stayed there only a moment, then fell out by itself. Not long after this, she died.

As I held her in the vet’s office, she cried in fear. The sound was like a small horn playing a single plaintive note. No amount of soothing could make her stop. The vet said Bitey might be hallucinating. Of course, you hear of humans doing that at the end, as they pass into what may be the next world or one of the worlds they traveled through on their way to this moment. On his deathbed F.’s father called out for his mother. She’d died when he was a small boy, disappearing into the hospital to be treated for something no one bothered to explain to him and never coming home. How long had it been since he’d called her name? All those people we keep folded inside us, filed away like old deeds. We can’t bear to throw anything away. As awful as it was that my cat was dying, it seemed worse to me that she was dying in fear. “It’s okay, honey,” I kept murmuring to her as she let out those monotonous dying calls and stared in horror at a spot on the ceiling above my left shoulder. “You’re safe, you’re safe.” I don’t think it could be called lying. A cat has no way of knowing what “safe” means.

In my closet I have a box of letters I collected from my mother’s apartment after her death. Many of them are written on that ethereal blue aerogram stationery that signifies foreign travel far more than a postcard of the Colosseum or a camel can, as well as the frugality of a time when people worried about the weight of a letter. Some of the letters are from her parents, written during the war when my mother first came to this country from Europe. Some were written later on, when she was traveling. Some are from me. I found an entire bundle of the ones I used to send her from summer camp. I rarely had much to say. Today I caught a fly ball (which was probably a lie). We had crafts; I made an ashtray. There are letters from my mother’s cousins, the ones in Boston, the ones in Moscow, the ones in Tel Aviv, the one in Winnipeg whom she held in awe because he wasn’t just rich but a lawyer and not just a lawyer but a “solicitor,” a “Queen’s counsel.” The way she fawned over him used to drive me crazy.

At the time I emptied my mother’s apartment, I took out as many as five boxes of letters. But over the years I culled them the same way I culled her other papers, throwing out statements from long-closed bank accounts, instruction manuals for appliances that had broken years before. I used to go through her letters every year or so, when there was something else I was trying to avoid doing. In this way, I was able to get rid of the ones I thought ephemeral or meaningless. Still, many letters, especially the older ones, are in foreign languages—German, Russian, Swedish—and I can’t bring myself to get rid of them until I know what they say. They may turn out to be as inconsequential as the ones I chucked: thank-yous for wedding or baby presents, records of long-ago holidays when nothing happened. We went to the museum of arms and armor. Emil was deeply interested in the arbalests. Munich turned out to be foggy and unseasonably cool. Your uncle was struck by the number of soldiers in the streets. But they may say more than that. I keep promising myself to get them translated.

After Bitey died, I was in no hurry to adopt another cat. I was surprised at how sad I was. Every time I entered a room, I looked down reflexively and was stricken not to see her. The entire house became suffused with her absence. It was almost the opposite of what happens in “I’ll Be Seeing You.” I saw her nowhere. The bed was a bed without her on it; the armchairs were empty of her. The dining table had no black cat lounging on a heap of mail, waiting to scatter it when she was shooed off. It was more constant, more preoccupying, than any grief I’d known before. A month after my father’s death, I’d flown to Paris to hook up with a girlfriend who’d gone overseas for graduate studies. It was just before New Year’s and very cold, the streets around Les Halles powdered with light snow. Almost from the moment of my arrival, I’d figured out that L. had lost interest in me, and my disappointment displaced whatever else I was feeling. Every few blocks I’d have to stop in a bar for an Armagnac and a coffee, the coffee to disguise the Armagnac, make it look like some species of creamer served in a balloon glass. Only after I came back home did I remember that my father had lived in Paris for a few years before the war; he’d gotten out just before the Germans marched in. The whole time I was there, it never entered my mind. Looking back, I see an inverse symmetry between my response to my cat’s death and my response to my father’s: In one case, the lost object remained constantly present in my consciousness, which made the object’s absence from the world more acute, more haunting. In the other case, the lost object had vanished not just from the world but from the field of my attention, and to such a degree that I passed through a city that had once been associated with the object—had once been home to it, to him—without that connection ever rising to consciousness.

Can we speak of some lost objects as being more lost than others?

Oddly, for all the times I was reminded of my cat’s absence, I half believed that she was still there in the house. Some of this was because of how the other cats had behaved when F. and I came back from the vet’s office where we’d sat with Bitey at the end. Instead of greeting us at the door, the two gray tabbies, Suki and Ching, gazed fixedly down at us from the top of the stairs. When I climbed up to where they were sitting, they continued to stare past me. “What are they looking at?” F. asked from below. I turned to follow their gaze. All I saw was the floor of the vestibule, with its scuffed boards and inexpertly lined-up shoes. Suddenly I knew it was Bitey. “If it’s you,” I called, “come in. Please. You’re welcome here.”

I suppose that belief, which wasn’t really a belief but a more forceful kind of wish, was what made me keep looking for Bitey in every room I entered for weeks after her death. Whatever the impulse was, it wasn’t wholly mistaken. To keep the lost object in mind is to keep it alive. You hold it cupped in consciousness as you might cup a lit match in your hands to keep it from being blown out in the wind. This, according to the philosopher George Berkeley, is what God does with the entire universe, each of whose trillions of objects, down to its tiniest grains of matter, exists only because the Creator has thought of it, is thinking of it, sustaining it from moment to moment with the labor of his enormous and encyclopedic brain. I find this idea very moving, even though I have a hard time believing, as Berkeley did, that there is no such thing as matter. But then, Berkeley, who was also an Anglican bishop, seems to have felt that it was only a short step from believing in the existence of matter to disbelieving the existence of God. You can imagine what he might’ve felt about appointing gays and lesbians to the clergy.

Berkeley is an example of somebody whose ideas are consistent. Mine are not. I grieved for my cat even as I nursed the fantasy that she was still present in our house in a small town in the Hudson Valley, where F. and I had moved when we began to have faith in our relationship, this third thing that had arisen between us, as if from the vapor of our breath, and then condensed, the way your breath condenses on a window pane, so that you can write a name in it. The consequences of these beliefs were the same. On sad days, I could barely pay attention to the surviving cats. On days when my spirits were higher, I worried that getting a new cat would be unseemly. Thinking about the etymology of that word, its roots in “seeming” and “seeing,” I ask myself who or what might have been offended to see a new cat romping around our home. But, of course, I know the answer. I was thinking of Bitey. Bitey would see.

In many stories of the supernatural, a ghost is summoned back by jealousy, a fury at being replaced.

Here I mention that for a long time after her father’s death, F. would lay out a small plate for him at mealtimes, placing on it small portions of the foods he used to like: olives, nuts, cheese, a bite of meat or fish. Sometimes she’d set out a fancy gold-rimmed goblet in which she’d pour a single swallow of wine. She, or maybe her father, favored reds. And the last time I visited my mother’s grave, I brought along not the usual flowers but a box of chocolates, an expensive gift assortment. I waited till I was about to leave, then set the box down by her headstone. I may have said, “Here, this is for you.” I haven’t been back since, and maybe that’s because some part of me doesn’t want to know if the chocolates are still there.