7

THE ANNOUNCEMENTS THAT ECHOED THROUGH THE wide spaces of Myrtle Beach International Airport made me think of death. It was the way they alternated warning and invitation. “If you are carrying more than three ounces of any liquid, gel, or cream, please place it in a Ziploc bag and put it in a receptacle.” “All Gold Club members, passengers with special needs, or passengers with small children are welcome to board at this time.” “Do not accept any item given to you by a person unknown to you.” I had a picture—I was probably remembering it from a movie—of some antechamber of The Forever where angels sort out the new arrivals before herding them to their respective gates, Gold Club or Economy, praising the virtuous and hectoring the damned.

I’ve never been especially scared of my plane crashing. What I’m scared of is the minute before: the unending, spiraling fall in which I’ll either be spun about the cabin or mashed into my seat with my face warped in an Iroquois mask of disbelieving terror, cheeks skinned back from my teeth. I’m scared I may scream. I’m scared I may piss myself, and be seen screaming and pissing myself. For years, I forestalled this potentiality by telling God that if it was between sending the plane down and killing me with a heart attack, he could give me the heart attack. The hope was he’d think I was making the offer out of concern for my fellow passengers. Sometimes I expressed it as a prayer, especially once during a lurching flight from Ho Chi Minh City to Vientiane in a Chinese-built prop plane that seemed to plunge 1,000 feet every time we passed over a gap in the mountains. Most of the other passengers were families with small children, and in my address I made a big deal about that, murmuring, “For the sake of these innocents,” in a ripe interior voice that would have sickened a Republican presidential candidate.

On October 2, as the plane taxied down the runway, then flung itself into the air, I changed my prayer. Please get me home safely so I can find my little cat.

The setting sun sent its fire through the windows. The hair on my arms was incandescent; the woman sitting beside me might have been made of brass. Looking down, I could see a path of light spreading across the ocean. I don’t believe in a god who responds to petitions. What is God, a mayor? The truth is, I never cared that much about the other passengers, not even those adorable Laotian kids.

One of the things F. and I still agree about is that it started going bad after we moved from the house on Parsonage Street. Maybe it was just that our lives were simpler there, in the mechanical sense. Living in the village, we could walk or bike to shops and restaurants or, when Wilfredo was visiting, down to the little public park to feed the ducks that paddled up and down the slow-moving creek. We didn’t argue about who was using the car. We were content with simple entertainments, especially reading aloud, whole books straight through, none of this PoMo skipping over the boring parts. F. is an expressive reader, and her interpretation of certain characters approached genius. One night we were doing the scene in Oliver Twist in which Bumble the Beadle is putting the make on Mrs. Corny, the grasping workhouse matron. “Are you a weak creetur?” he asks her meaningfully. I may have put a hand on F.’s thigh. She looked over her shoulder at me in a way that was at once flirtatious and reproving, and she read the next line not like somebody pretending to be modest but like somebody who on reflection realizes that she actually is modest, who knew? She lowered her eyes. “We are all weak creeturs.”

The cats were safe on Parsonage Street, if you discount one of them disappearing for a month, which was awful for us but for Bitey was probably an adventure. Because the street dead-ended, we could let Biscuit loll on the warm asphalt of the road beside the yard. Nobody minded slowing down or even coming to a stop if she didn’t care to get up. She’d lie there, turn her head to see what was making the noise behind her, then go back to licking her paw, and usually the driver would just back up and steer around her. Sometimes he’d give a short tap on the horn, as if to say, “Ta-ta.”

I used to complain about how dowdy our house was, but the dowdiness suited us. It curbed our (or maybe I should say my) grandiosity, reminding us (or me) that we lived in a house that had carpeting on its stairs and blue-and-white shepherds and shepherdesses minueting on the wallpaper: F. must have seen them minueting as she skidded past them down the stairs. For the same reason, it helped that only a small yard separated our house from our neighbors’. Day after day, we did more or less the same things in our yard as they did in theirs: we brought in bags of groceries and put out bags of trash; we planted flowers and vegetables and weeded the beds with the hoe we’d bought at The Phantom Gardener; we grilled salmon on a rusty Weber while playing music on the stereo. When we cooked, we listened to Garbage and Sonic Youth. The people behind us played a C&W station. The music was cheerful; those boing-ing pedal steels made me think of the Looney Tunes theme. But the male voices were thick with self-pity, and the words often seemed to be about dropping a bomb someplace or punching somebody in the mouth for questioning your right to do it. Well, I doubt the neighbors were any crazier about Kim Gordon. I used to imitate the husband ordering their small dog to “go peepee, go peepee!” F. and I argued about whether he could hear me. I always said he couldn’t, but for all I know, while Toby Keith was hollering, “We’ll put a boot in your ass, it’s the American way,” the neighbor was imitating us calling our cats in babyish voices. “Bitey! Ching! Tina! Biscuit!” What kind of dumbass is dumb enough to think a cat’s going to come if you call it?

Almost the first thought that came to me when I learned Biscuit had gone missing was that this would never have happened if we’d stayed in our old home. I don’t mean just for practical reasons but for moral ones. We were being punished for wanting a bigger house with more land around it, for wanting not to have to listen to our neighbors’ music. We were being punished for wanting to live like gentry instead of tenants.

I know F. felt something like that when we lost Gattino.

At the time, it didn’t feel like we were getting above ourselves. We’d been on Parsonage Street for almost eight years. The house had gotten cluttered; the boxes we’d stored in the basement had grown coats of mold. One autumn the landlord got ambitious and had the red siding peeled off and replaced with the beige vinyl he used on his other houses. His workers strewed the yard with red aluminum shrapnel and tufts of bubblegum-colored insulation; all our flowers died. What had been wrong with our red aluminum? When we got an offer to rent a bigger place in the next town to the north, we jumped at it. The property had a barn and a big garden with lilac trees and peonies—beautiful peonies, as big and fluffy as cockatoos. The landlord was a friend of friends. At the time I was dumb enough to think of that as an asset.

Maybe it was the prospect of moving that put me in an expansive mood. F. was going to a residency in Italy that summer, and we decided I’d meet her afterward so we could spend two weeks driving through the country between Tuscany and Rome. It would be our first vacation since our honeymoon and the first real trip we’d taken together to another country. I don’t count the time we’d gone to Russia two years before because that was for work and its picturesque high point, a midnight boat ride down the canals of St. Petersburg, ended with F. hitting her head on the underside of a low bridge and getting a concussion. There’s a photo I took of her just moments before the collision, which, mercifully, was slow and very soft, a stone tap. In it, she gazes over the tops of her glasses at something just beyond the frame, her skin translucent, her hair spectrally pale. Her expression is at once intent and vague, the expression of someone peering through a mist with such concentration that she fails to see the solid object that’s about to rear out of its depths and smack her on the head.

At the time we made our travel plans, I had no job to speak of and was already in debt. Looking back, I wonder what I was thinking. Probably, I was thinking of being a lover again rather than a husband. The word “husband” means both a male spouse and, in its verb form, to use resources economically, to conserve. I bought a $700 plane ticket; I booked hotel rooms that cost €100 a night. This was not husbandry. It’s true I spent that money with the aim of making F. happy, but a wife’s happiness may not really be a husband’s business. His business is to take care of her, to ensure she has fuel to make a fire with and meat to cook on it and a roof to keep off the rain. It’s to protect her and their children from every danger that a malignant world might launch at them. It’s to be the guarantor of her modesty. Neither Adam nor Abraham tried to make their women happy—when Sarah laughed, she laughed out of incredulity and bitterness—and if you had suggested that they ought to, they, too, would have laughed, except they would have been laughing at you. Changes in the husband’s role seem to have been underway by early in the Christian era, for Paul says that a married man will care for the things of this world “that he may please his wife” (I Cor. 7:33). This is why he thought men ought to be celibate.

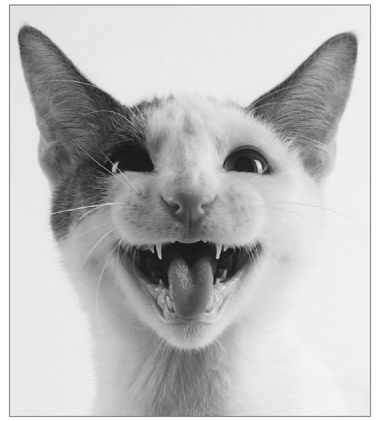

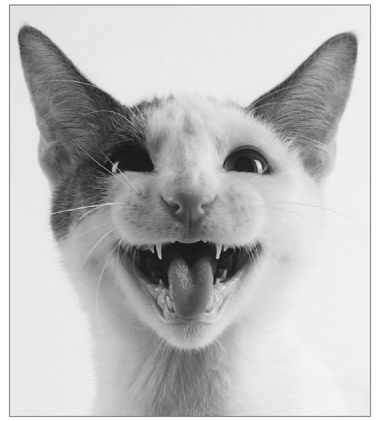

Making a woman happy is the task of a lover. Considered purely as labor, this isn’t as hard as having to see to her well-being and safety, but it requires paying close attention to things that are unquantifiable, even invisible—to shades, nuances, emanations. Good lovers seem to have internal receptors that detect the most spectral traces of female longing and pleasure: I don’t mean just the sexual kind. One may think of those receptors as a counterpart to the vomeronasal organs cats deploy in flehmen, the open-mouthed sneer with which they take in interesting odors.

A cat’s sensors are designed to assess scent signals from a variety of sources, but a lover focuses his powers on a single object or on the class of which that object is a member: a woman or women. From moment to moment, often quite unconsciously, he trains his attention on the object to determine what she wants from him: a back rub, some home-baked bread, lingerie, chocolate, poetry, a sympathetic ear, a comforting shoulder, a hard dick. Some men understand the value of these things; others snort, What bullshit! Isn’t it enough I change the fucking oil? It may be that marriage began its present slide at the point when husbands decided that they too needed to be lovers. Some will say that women first gave them the idea, but it was probably someone in magazine publishing or a florist or a manufacturer of toiletries who was looking for a way to make men buy cologne. And let’s not forget the makers of ribbed condoms.

During the time F. was alone in Italy and I was waiting to join her, she took in a small kitten. She found it in the yard of a derelict farmhouse near the residency, where she was steered by one of the staff. “Do you like little cats?” this woman may have asked, in the manner of pimps everywhere. “I have some adorable ones to show you.” The kitten was very sick, its nose gummed with secretions, its belly hard and swollen with worms. When F. picked it up, which she could do because it was weaker than its littermates, she saw that it was blind in one eye. At first, she meant only to have it treated by a local vet before releasing it back in the farmyard to gambol gauntly with its brothers and sisters. But over the weeks in which she kept it in her rooms, dosing it with the medicines the vet had given her, she became attached to it. And the kitten, which early on had viewed her with a feral creature’s wary pragmatism, grew attached to her. She told me about it in phone calls. Yesterday the kitten had followed her about with its tail raised. Today while she was working, it had climbed into her lap and teethed on her fingers. Last night he had slept with her. I noted the change of pronoun. Then F. told me she wanted to bring him back to the States. She said she loved him. More important, the kitten loved her, seemingly in violation of his—its—nature. She had taught him love, or maybe infected him with it, and if she left him back at the farm, she was scared he’d be stuck with this feeling that was too big for him, that was too big for most humans, and he would suffer. My heart sank. It was so typical of F.’s love, which is so often called forth by an apprehension of the object’s doom. Why couldn’t she have fallen for a kitten that was healthy and saw out of both eyes, an American kitten? But then I suggested a name for him: Gattino. This is a stupid thing to do with a creature you don’t want to get attached to.

I got to the residency late in the afternoon, after driving four hours from Milan in a rented Lancia on roads that wound around the hillsides like a long caress. I parked in front of a low stone tower and got out of the car. F. ran into my arms. She glowed as if suffused by the sun. Her hair and skin were golden. She smelled of rosemary. Gattino was waiting in her bedroom. On seeing me, he scrambled under a dresser, and I had to kneel down and talk to him soothingly before he would come out. He had long legs—he was going to be a big cat—and his veiled eye and big, blunt nose gave him a look of jaunty toughness, like one of those skinny Neapolitan kids who grows up to be a prizefighter or a gigolo. He prowled the table, sniffing my wallet and car keys, then lay down with us on the bed. That night, he slept on top of me, purring.

There was no question of taking him with us while we traveled, and for a while I worried that F. would want to call off the trip. She was afraid to leave Gattino at the vet’s. She was afraid he wouldn’t be cleared for immigration or importation, I’m not sure what to call it. I know he needed to be given a clean bill of health, and there was some doubt he’d get one. He was still frail, and there was that eye. The clinic was crowded, filled with the acridness of caged animals and their outcries of fear, hunger, and anger. An attendant placed Gattino in a cage next to one holding a large dog, bristling with muscle, that barked and slavered. Gattino cried. F. began crying too. I’d seen her cry only once or twice since her father’s death, maybe over Wilfredo. But who wouldn’t cry, seeing a kitten placed in a cage beside an immense dog that wanted nothing more than to eat his small heart? Even here, though, you could see his spirit. Instead of cowering, our cat (already I was thinking of him as ours) peered out at his tormentor with an intrepid forward tilt of his ears. His tail was lowered, but it wasn’t tucked between his legs. It was out behind him, and this made him look as if he were about to launch himself forward like an arrow at a target. At the very least, he would hold his ground.

For the next two weeks, I was F.’s lover again. We drove as fast as you can drive in a little car without scaring yourself into incompetence; out of the corner of my eye, I could see my wife’s bare feet propped on the dashboard, and the casualness of her posture reassured me that I wasn’t about to get us killed. We walked hand in hand through the cobbled defiles of hillside towns, up stone steps whose sheerness put us in an allegorical frame of mind. There was usually a cathedral at their summit, and above its spires the same blue sky where Signorelli saw angels swooping. We stood on battlements, looking out at wheat fields and grape vineyards that had provisioned the Borgias while the shadows of clouds lengthened over them, turning the rows of grain a dull bronze. We sat in restaurants whose white linen glowed in the candlelight; surely all those restaurants can’t have been candlelit, but in retrospect it seems that way. Each dish was fundamental. It tasted of the elements that had produced it, tomatoes of earth and sun, a roasted dorado of fire and the sea. The waiters masqueraded as layabouts. All evening they looked at the pretty girls on the next terrace or an especially slick motor scooter or a platoon of German tourists uniformly burned the color of raw salmon—at anything but you until the moment you wanted something, at which point they appeared at your side and said, “Mi dica.” We hung out beside fountains that might have been the originals for the fountains where I hung out as a teenager, out past curfew, looking for a girl to be with, and now at last, thirty-five years later, here I was, with her.

Most of the pictures I took in those places are pictures of her.

Among literary forms, the lyric is the lover’s mode, for that’s how a lover experiences the world, as a series of isolated moments bright with feeling, like stills from a movie whose intervening frames have been excised. The world starts with the love object, and it ends with her. Whatever else it contains—sun, moon, stars, a blue flower, a blanket crumpled on the grass, a dark wood—exists only to reflect the loved one or otherwise call attention to her, or to what she evokes in the lover. The sun and moon are the bodies whose light he sees her by; the stars are the jewels he would give her if only he could climb into the sky to quarry them; the blue flower is what he gives her in their place. The blanket is where he lies with her on the grass on a summer evening, the first fireflies bursting silently in the still air. He sees them out of the corner of his eye. The rest of the time he is looking at her.

The lyric is beset with paradox. The moment it evokes may be brief as a heartbeat, yet it seems to go on forever, an eternity in which Sappho can raptly take account of everything that is happening inside her:

. . . if I meet

you suddenly, I can’t

speak—my tongue is broken;

a thin flame runs under

my skin; seeing nothing,

hearing only my own ears

drumming, I drip with sweat;

trembling shakes my body

and I turn paler than

dry grass.

In Gerald Stern’s “Another Insane Devotion,” the narrator’s sudden, shattering encounter with one of Rome’s ravenous street cats frames an entire history of lost love:

. . . I have

told this story over and over; some things

root in the mind; his boldness, of course, was frightening

and unexpected—his stubbornness—though hunger

drove him mad. It was the breaking of boundaries,

the sudden invasion, but not only that it was

the sharing of food and the sharing of space; he didn’t

run into an alley or into a cellar,

he sat beside me, eating, and I didn’t run

into a trattoria, say, shaking,

with food on my lips and blood on my cheek, sobbing;

but not only that, I had gone there to eat

and wait for someone. I had maybe an hour

before she would come and I was full of hope

and excitement. I have resisted for years

interpreting this, but now I think I was given

a clue, or I was giving myself a clue,

across the street from the glass sandwich shop.

That was my last night with her, the next day

I would leave on the train for Paris and she would

meet her husband. Thirty-five years ago

I ate my sandwich and moaned in her arms, we were

dying together; we never met again . . .

One moment stands in for other moments or contains them, hundreds, thousands, a lifetime of moments curled inside that one like the strands of DNA inside the nucleus of a cell. What makes that possible is memory. Memory stretches out for fifty-seven lines the moment in which the poet eats beside the starving creature to which he’s surrendered a scrap of his sandwich and packs within that interval days and nights of lovemaking and a lifetime of reckoning and regret. Unless it’s literally written in the moment, scrawled between kisses on a cocktail napkin on the nightstand, the lyric is a memory masquerading as the lived present. And its beauty is that it feels like the present: it feels more like now than now does.

A further paradox is that the lyric, although inspired by love for another person, often leaves that person in shadow. All Sappho tells us about her beloved is that her voice is a sweet murmur and her laughter is enticing. Of Stern’s we know this: she was married, or was about to be; they floated naked in the sea and moaned in each other’s arms; she was going to have a baby; it was his. This isn’t much. And yet Stern’s lover haunts his poem as Sappho’s lover haunts Sappho’s, manifested in one poet’s outrushing of memory and the other’s burning speechlessness. Both poets evoke a hidden object by registering her effect on them. In the same way, by measuring the perturbations in a star’s orbit, astronomers can determine the existence of a black hole.

My favorite photo of that summer is one I took of F. in Volterra. There was some wind that day, and her long hair is blowing about her face. It was F. who showed me that if you cover one half of a face in a photograph, its expression changes, sometimes so dramatically that you seem to be looking at an entirely different face, animated by feelings that are barely discernible in the original. If you move your hand to the other side, still another face appears. In the photo I’m speaking of, F. seems, if not happy, confident in her loveliness. Her gaze meets the camera boldly. But when I cover the left side of her face, the other half turns watchful and melancholy, with a nostril dilated as if from crying. And when the experiment is reversed, the half face that peers out from behind your hand is taut with defiance, as if she were daring you to breach her privacy, and the half smile that tugs at the corner of her mouth is devoid of pleasure.

It was Rome that F. liked best. It was more alive than Florence or Siena; it didn’t just unroll its past and invite you to sample it. It gave you sexy teenage couples horsing around amid the ruins, a mezzo with no chin and a tubby baritone singing arias in a church. F. marveled at their plainness. She loved it that people so plain could enact desire frankly, without apologizing, eyes flashing, bellies heaving. Yet, even in Rome, she was tormented by thoughts of Gattino. She prayed for him in churches. She called the veterinary clinic to ask if he was eating. She worried that the vet wouldn’t be able to get him cleared for travel: there were rumors of bad blood between him and the regional official—the head veterinarian of the entire region of Tuscany—who was supposed to sign the papers. The airline specified that cats could only travel in-cabin in carriers of certain strict dimensions, and nowhere could we find one the right size. The variety of merchandise in the pet shops was jaw-dropping. There were cat carriers covered in soft leather and rip-stop nylon, cat carriers belted like trench coats. All displayed the Italian genius for design, but all were off by centimeters in one or more dimensions. F. took it as a bad sign. “They won’t let him on the plane.” I told her they would. “They’re Italians, sweetheart, they don’t give a shit about bureaucracy.” But even as I said this, I remembered that they had also more or less invented it. I think it was the Romans who came up with the first initialism.

S.P.Q.R.

We drove back to Tuscany and reclaimed Gattino from the clinic. He looked more robust, his nose was dry, and when we presented him to the provincial vet, he stepped out of his new carrier as if he expected to be admired. But the provincial vet looked at him disapprovingly; he didn’t look at us at all. The cat, he said, was too sick to travel. Our vet, who had come there with us, argued with him—politely, he was conscious of the man’s power. His hands made soft, beckoning gestures. The official kept shaking his head. “No, no, no.” He may have said, “I don’t have time for this.” F. looked as if she might faint. I blurted something in Italian: “Senza la mia moglie e me, questo piccolo gattino non ha nessun’ amico in tutta l’Italia!” (“Except for my wife and me, this little kitty doesn’t have one friend in all Italy!”) Both vets looked at me, but it accomplished nothing. Well, it embarrassed F., and that may have distracted her a little from her unhappiness.

On leaving the interview, our vet told us that he would go to Umbria the next day and have their head vet stamp Gattino’s passport. It would be no problem, he assured us: the vet was a friend of his. And when he gave them to us just before we left, we saw that Gattino’s papers really did look like a passport. They even had the same burgundy cover the EU uses on the ones it issues human beings.

I spent an hour or so in the sky, gazing down at the profile of the continent and nodding and smiling as the woman next to me, who had turned from brass back to soft, perishable flesh, told me about the grandchild who was about to be produced in time for her arrival. When I told her I was going up to New York to search for a missing cat, she looked at me with what I was pretty sure was pity. Was it pity for someone who was looking for something he was extremely unlikely to find or pity for someone who had no better outlet for his affections than a cat? “Well, good luck,” she said. It was as if I’d told her I was on my way to have surgery for a brain tumor. I thanked her.

Husbands have written lyrics, but they aren’t really suited for it. The lyric form can’t express the state of being a husband, for that is not about feeling but being. A man becomes a husband by saying, “Till death do us part,” or, if he’s squeamish about the d-word, “As long as we both shall live.” In either case, he rarely knows what he’s getting into. Feeling is brief; being has duration. A husband can feel many things, but he is one thing, and he may go on being that thing long after the feelings that brought him to it have passed. What feeling lasts a lifetime, except maybe statistically, the tissue-thin temporal slices of love stacking up higher than those of irritation, dislike, even hatred by so many microns that measuring those stacks at the end you can plausibly say, We were happy? Or I was?

Being a husband is also about action, which is why the husband’s ideal literary form is narrative. The Odyssey, which is sometimes reckoned the first novel, is the story of a husband who’s trying to get back to his wife. Most husbands don’t have to do as much as Odysseus does to accomplish this, or for as long, and they don’t get to do it with cute nymphs and a princess. They go out on the day’s errands, buy some things for the missus, and stop at the fitness center for a sauna. There’s a funeral where they have to pay respects. They make some business calls, have a little lunch. At a fund-raising event, a mean drunk tries to pick a fight with them; they leave shaken. Later, around the time they ought to be going home, they run into another drunk. It’s the son of an old friend, grown up since they last saw him but he hasn’t learned how to hold his liquor yet, and knowing the kinds of grief a drunk kid can get into, they tag along with him as he weaves in and out of every dive and blind pig in the city, even a whorehouse. God knows what would happen to the little dipshit if they weren’t around to keep an eye on him. It’s late, and the kid’s still shwacked, so they take him home to crash on the sofa. The wife’s asleep in the bedroom, or maybe pretending to be. No way of telling if she’s mad at them for coming home so late or. So they lie down beside her, and in a while they fall asleep too. Change a few particulars and you have Ulysses.

In narrative, order is crucial, chronological order especially. Consider how that story would read if the husband stopped by the house before the unpleasantness with the drunk. Consider an Odyssey in which the hero comes home in the first twenty pages, kills the suitors, then leaves again to make time with Calypso. Sequencing is also essential to husbandry. A husband plows before he sows. He pays the rent before the premium cable. He buys heating oil before he buys a snowblower, though it would be nice to have one, especially after pulling his back like he did shoveling out the driveway last winter and getting a case of sciatica that his wife charmingly kept calling “ass-leg.” He doesn’t book an Italian vacation before he finds a job or collects an advance from his publisher, and certainly not a month before he and his wife are supposed to move to another house. Before leaving the underground parking garage in a scenic village famed for its museum of Etruscan artifacts (and, he later learns, for its appearance in Stendhal’s On Love), he makes sure he knows where the ticket is so that later he doesn’t have to spend a quarter of an hour futilely slapping his pockets while behind him a queue of Italian cars grows longer and longer and their drivers honk at him in mounting, polyphonic fury. Before changing his return flight so that he can escort his wife and her new kitten from Florence to Milan, he demands more than a customer service representative’s assurance over the phone that the airline will book his baggage straight through to New York, knowing that citing such assurance later to a desk clerk at the Milan airport, where his baggage has not been checked through, will have about as much weight as it did to insist, when as a child he was made the victim of grown-ups’ peremptory rule changes, “But you said . . . ”

This was after I’d spent a half hour waiting for my bags to thump onto the carousel and then wrestled them upstairs to the gate for New York, where a line of passengers shuffled forward beneath the high ceilings, crisscrossing other lines bound for Prague or Cairo or Miami. Incomprehensible announcements in many languages buffeted us. I tried cutting ahead; a guard yelled at me. “I’m supposed to be on that flight,” I told him. He shrugged. The shrug was a way of distancing himself from his own authority, of disguising “I don’t want to help you” as “It can’t be helped.” In that way, it was very Italian. F. had already boarded. An attendant let me call her from the counter. We exchanged despairing good-byes. Who knew how long I’d be stranded here? Abruptly, her tone lightened. “Gattino’s doing really well,” she told me. “He hasn’t made a peep.” I may have asked her if he missed me, and she may have sworn, in a voice rich with theatrical insincerity, that he did. I remember laughing, and I remember the attendant looking at me with what, given the circumstances, was probably surprise.

I spent the next hour or two waiting in front of various counters, wobbling between abjection and fury. (Under similar conditions, Italians went straight to fury: F. told me that on the flight over, she and her fellow passengers had been marooned for hours at this same airport, where the Italian men had expressed their displeasure by racing up and down the stairs, shouting oaths, and tearing off their suit jackets and flinging them to the floor.) Getting home less than three days later cost me another $800. Actually, if you count the price of the charmless airport hotel where I spent the night and ate the only bad meal I ever had in Italy, it cost me more.

A limitation of the lyric mode is that it typically enacts only one big feeling at a time, or sometimes a sequence of feelings like the rooms in a museum through which the visitor passes, looking first at the Cimabues, then the Giottos, the Botticellis, the Ghirlandaios, a Michelangelo displayed behind bulletproof glass. Somewhere there may be some early Masaccios. This limitation may be a natural consequence of the immense, transfixing energy those feelings possess, whether in themselves or through the amplification of poetic language. And it’s true that looking back, the lover is likely to remember his feelings the same way. Each filled him so completely that to add even a dropperful of another emotion would have burst his heart. For this reason, even the most despairing lyric conveys a kind of joy. Few joys are greater than the joy of feeling one thing completely, to the utter exclusion of anything else. It’s probably not too different from what the angels feel as they sing beneath the dome of heaven, only the angels feel it for eternity.

A husband rarely has the luxury of feeling one thing completely. He’s too busy checking the entries in the Michelin guide and copying road directions from his laptop onto a piece of paper so his wife can read them to him as he drives instead of fumbling with his stupid BlackBerry. Much of the time, he doesn’t know what he feels at all. And some of the feelings that impinge on his consciousness are so devoid of lyricism, so tepid and dishwater gray, that no poem could be written about them unless it were by Philip Larkin. The shame of hearing a dozen drivers backed up at the exit of a parking garage sound their horns at him—of feeling the horns’ blast like a blow between his shoulder blades—as he walks over to the cassa to purchase a new ticket, a shame compounded by the peevish thought that they could get out of here quicker if his wife would at least offer to pay the cashier so he could move the car as soon as the gate was raised. But she says her Italian isn’t good enough, and wouldn’t it be cowardly to subject her to the brays of the fuming motorists behind them, though maybe they wouldn’t honk like that at a woman? No, they would.

The impatience that mars his pity as he watches her weeping over what is, after all, just a cat. Even as he feels this, he understands that “after all” and “just a cat” are phrases he will have to keep secret from her until the day he dies.

The white-knuckled anger of circling endlessly around the Aventine in his flimsy Lancia, crossing and recrossing the Ponte Sublicio or is it the Ponte Testaccio? Impossible to tell, since the traffic moves quickly and the streets don’t have proper signs with their names on them, only stone plaques on the sides of buildings that might be legible to somebody on horseback, if the streets were better lit, which they aren’t. With each circuit, he becomes more angry—who built this fucking city?—but also more afraid, because it seems they’ll never find the street they’re looking for, just keep whipping around and around until they run out of gas or get rear-ended by one of the cars behind them: by Italian standards, he’s driving like somebody’s nonno.

But his wife wants him to slow down. In the glow of the headlights, her skin is ashen, and the small vein above one eye is throbbing. “Don’t you know where we are?” she pleads. Through clenched teeth, he says, “In principle.” Her voice gets higher. She’s tired; she’s hungry; she’s dehydrated. They should never have driven into Rome. He says she’s right and imagines wrenching open the passenger door and kicking her into the street. She begins to whimper, a horrible sound. It’s this that makes him pull over to a curb. “Okay,” he says, “we’ll stop. Look, look, I’m stopping.” There is a space—he doesn’t know if it’s legal, but fuck it, let the fucking polizia give him a fucking ticket. He tells her to get out. She looks at him in fright. Can she have guessed what was in his mind a few moments ago? He makes his voice softer. “Let’s get out and find something to drink.” He takes her by the hand and leads her to a little grocery store whose lights cast a bluish-white trapezoid onto the sidewalk. Stepping inside, he has the momentary illusion that they’ve entered a bodega in his old neighborhood in the city, a place where you could buy a bag of plantain chips and a Diet Coke: the Diet Coke in Italy is terrible. He asks for a bottle of water and hands it to her. “Drink,” he says. She protests. They don’t know where they are. “Shut up,” he says, but he says it gently. “Just drink.” It’s only watching her tilt her head back and take long, grateful swallows from the upended bottle—a creaturely gratitude that isn’t directed at him but at the water itself—that he remembers he loves her.

We don’t think of cats as beings that feel two things at once, but this is one explanation—as far as I know, only an anecdotal one—for why they sometimes lash their tails. And when Bitey was dying, F. noticed that Suki, who usually was just cranky, seemed both angry and sad. For most of the night, she remained in the narrow hallway outside the bathroom where my cat sat listlessly in the tub. Her expression was unmistakably a glare. But once F. pointed out that her eyes were filled with liquid. The liquid was clear and bright, and it ran down the gray tabby’s cheeks, and I don’t think it’s too great a stretch to call it tears. They may or may not have been tears of grief.

By the time New York appeared below us, it was dark. Most of my memories of landing there take place at night, though when I’d come back from Italy the year before, it was afternoon. That may be part of why it felt so anticlimactic. On October 2, 2008, my plane landed at night, the voluptuous night of New York in autumn, violet as ink and lit from beneath by the radiance of its traffic, not just the vehicular kind but the traffic of money and its shape-shifting surrogates—collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps—the traffic of power, the traffic of beauty, the traffic of appetite, of talent, of sex. Everything was moving; every lighted window signaled others. And in darkened offices, machines spoke to other machines thousands of miles away in a language of pulses, clicks, and blinking lights. An immense conversation was taking place below, and the aircraft circled it the way a newcomer circles the fringes of a party, a party where his welcome is uncertain; he sees nobody there he knows.

A wing dipped, then sliced across the face of the moon. Slowly, we dropped.

We didn’t get a parking ticket that evening in Rome, but ironically, I got one later, in Arezzo. I’m speaking figuratively. There was no physical ticket, and I had no idea I’d done anything wrong until some months after my return to the United States, when I received a citation from the Polizia Autostradale of the Region of Tuscany charging me with illegal parking and demanding €100. I tore it up. A while later, I got a second citation in which the fine was raised to €150. This time I wrote back, asking (in English) for some evidence of the violation. None was given me. Instead, the citations kept coming and the fine kept rising until it reached €250. At that point, I took down my Italian dictionary and wrote back:

Egregi signori,

Ho ricevuto la vostra domanda di pagamento per parcheggio illegale nel commune di Arezzo la notte del 28 luglio 2007. Purtroppo, devo rifiutare di pagare quest’ am-menda eccessiva e ingiusta. Non c’era nessun segno o avertenza riguardo al fatto che era vietato parcheggiare nel posto in questione. Nessuno ha lasciato qualche tipo di avviso sul parabrezza della mia macchina. Inoltre, sono disoccupato e pieno di debiti, e la ultima bolletta che pagherò è una di quasi quattrocento dollari data per una infrazione che non ho mai commesso, e certo non per colpa mia.

Distinti saluti,

______________.

There were no further requests.

To be honest, this is only an approximation of my original letter, which I didn’t keep. At the time, I figured that either it would achieve its purpose or it wouldn’t, and if it didn’t, I would just keep stonewalling until the Polizia Autostradale got tired of dunning me. Maybe it was naive to assume they wouldn’t hit on the expedient of putting a lien on my bank account, but then again, if they could do that, Italy wouldn’t be going bankrupt, would it? The Italian of the original was almost certainly worse, since I dashed it off in a rage, and I doubt it included the word parabrezzo, “windshield.” Still, I was pleased with myself for having pulled off a letter of this kind in a foreign language, and I would have shown it to F. if I hadn’t been afraid of reminding her of Gattino. By then he was gone and, I’m pretty sure, dead.