8

I DON’T REMEMBER CHECKING A BAG—I DON’T KNOW why I would have checked one for a short trip—but I know I was in baggage claim when I played back Bruno’s message. I have a clear memory of standing by a brushed-steel conveyer belt with my phone wedged against my ear and hearing his voice for the first time in almost a week; it sounded hesitant and apologetic. I thought it would be more bad news. He said something about Biscuit, but the next words were obscured by a thudding cascade of luggage that might have been the commotion of my heart. Is that what Ruskin meant by the pathetic fallacy? I had to play back the message to hear Bruno say he’d spotted Biscuit in the yard and almost succeeded in putting her back inside. He’d picked her up (only later would I appreciate the screwing up of will that must have demanded of him), but she’d scratched him (I could hear his incredulity and hurt) and gotten away. He was sorry. When had this happened? I kept playing the message back, but he never said. At the moment it didn’t matter; I was too happy. I called him; it went straight to voicemail. For once, I wasn’t irritated. I spoke in the praising tones one uses with very young children. How great was it that he’d seen Biscuit! He probably shouldn’t have tried picking her up, but his intention had been good, and at least we knew she was still alive and near the house, right? That was really great. Could he tell me just when this had happened? Oh, and I was in New York; I’d just landed. I’d probably be up there in a couple hours. No need for him to wait up for me, but if he didn’t mind, could he leave the light in the driveway on?

By the time I got home from Milan, F. had installed Gattino in a spare room on the side of the house. It had its own entrance, so the other cats didn’t yet seem to be aware of his presence. But Gattino knew we were somewhere without him. In the morning he raced to greet us at the door, and even if F. or I spent most of the day in the room with him, he was always crestfallen when we left, or so it seemed to me from the way he’d try to leave with us and, when nudged back, would sit down heavily and look up at us with his one eye. He’d gotten used to sleeping with us.

Maybe this was what F. meant when she said that love—the human kind—is too big and complex a feeling for a cat. It may also be too perverse, since it involves treating a self-sufficient adult animal as an infant, our infant, and in turn encourages the animal to behave as if it were one. Like every other creature, a cat in the wild will know the discomfort of wanting and not getting. It will know cold and hunger: kittens are supposed to have separate cries for each. A domesticated cat will be held against its will (witness the indignant squeak Biscuit would make when you picked her up); it will be shooed off dining tables and kitchen counters, though not F’s and mine, and have alluring objects like electrical cords snatched away from it. But in its natural state, a cat is mostly a solitary being. Its couplings are brief and scored to a soundtrack of screeches. Males are known to kill their young. It is a stranger to the pain of being separated from what it loves because it’s a stranger to love, or love is strange to it. Now we had introduced a cat to that foreign thing, that xenograft, and maybe to a new kind of pain. It was too early to tell.

That summer was one of the last times Wilfredo stayed with us. It was a bad visit, which was probably more our fault than his. We were in the middle of packing, and so everything we did with him, we did only dutifully. I’m sure he picked up on that; it may explain why he regressed. One morning in the kitchen, he told F. he wanted her to feed him his cereal. He opened his mouth expectantly, importunately, like a baby bird. We could see the remnants of his last few bites caked between his teeth. He was almost as tall as I was and had heavy breasts that embarrassed him so much he refused to take off his T-shirt when we took him swimming. F. told him not to be gross, though really, how could you expect an eleven-year-old boy not to be gross? It would be expecting him to forego the highest expression of who he was, or, really, what he was, the apotheosis of his boy’s smeary, spewing, burping, farting nature.

That was the summer he threatened to cut off my nuts. To put it in context, he made the threat after he’d learned we were planning to have Gattino neutered and immediately after he’d learned what neutering involved. I wouldn’t be surprised if he unconsciously equated the cat with himself: they were two young males with Latino names and some physical habits that F. and I considered repulsive. We knew it was time to have Gattino neutered because when excited, he’d begun to give off a rank smell, a jet of pure male horniness and aggression.

Every year before this, we’d taken Wilfredo home on the train, but this time we decided to drive to the city. I’m not sure why. F. was in a terrible mood. She was relieved Wilfredo was leaving, but she felt guilty about it. And for the first time, she admitted to being disappointed in him. She’d dreamed that through us he’d learn to Rollerblade and ride a bike and act in plays and write a book report he could get a passing grade on, and none of that had happened. Or rather, he’d learned to do some of those things, but as soon as he did, he lost interest in them, as if all along they’d only been items on a list that had to be checked off to get us off his back. In that way, he was as perfunctory as we were. With F.’s tutoring, he wrote an excellent report on The Call of the Wild. But I wasn’t terribly surprised later when I learned that he never handed it in. He’d written it: what more did we want?

On the drive to the city, F. sat beside me and talked about how worthless love was. How it arose out of the sensible needs of the organism but, at least in human organisms, so often morphed into something twisted and self-defeating. She wasn’t even sure there was such a thing as love. Abruptly, something small and soft bounced off her head and landed on the seat between us. It was a stuffed animal that Wilfredo had tossed at her from the backseat. He’d won it at the county fair the day before. “Here,” he said, in the helpful if slightly condescending tone of someone who’s found something you’ve been going wild looking for. “What do you call that?”

In time, Biscuit and the other cats began to loiter outside the spare room and peer in at its windows. One morning I came out to find that Gattino had succeeded in pushing out a screen and was sitting on the wet grass, looking quizzically about him. A few yards away, Zuni watched him with moon eyes, trying to decide whether to approach or run for her life. Did he have any clue that he was 5,000 miles from the place where a human being had first lifted him off the ground? Did the grass smell different from the grass that had grown in his farmyard? Were there different bugs crawling in it? I scooped him up and put him back inside, feeling him buckle and squirm, all sinew and short, coarse fur. He was getting to be a strong little cat.

I don’t remember if we introduced him to the others before the move. It would have been a bad idea, given the disorder of the house, the stacks of boxes and the stacks of books and dishes waiting to be boxed in their turn, the doors left open, the limitless, limitless opportunities for loss or breakage. But if you picture one of those wall calendars that are used to show the passage of time in old movies, each page of the calendar of that summer—and, really, of the preceding spring—would have the words “Bad Idea” scrawled across it, and when that page was torn away, underneath there would be another page that said the same thing: “Bad Idea.” It was a bad idea to have Wilfredo visit us before the move. It was a bad idea not to look inside the oven in the empty house we were about to move into. It was a bad idea not to run the washing machine. It was a bad idea to take the landlord’s word that heat would run $200 to $300 a month in winter and not ask to see some heating bills. It was a bad idea to trust him to remove the bags of old clothes and toiletries and ordinary garbage, though, thankfully not organic garbage—it didn’t smell—that had been left in the closets. When F. asked about the garbage, I said of course Rudy would take it away; we’d been to his and his wife’s Christmas parties. That was how F. had fallen in love with the house in the first place, though it was probably a bad idea to fall in love with a house she’d only seen lit by candles and Christmas tree lights, the same way it’s inadvisable to fall in love with someone you’ve only seen in dimly lit restaurant booths or in the roseate glow of a hotel room’s bedside lamp.

It was a bad idea not to ask F. if she wanted to think twice about moving to the new house. It was a bad idea to take her at her word when she said she didn’t. It was probably ill-advised, when she expressed misgivings about things like the garbage in the closets, to ask (or, according to F., yell), “Well, what do you want to do then? You want to just cancel? Fine, then you find us a place to live.”

It was a bad idea to hire a mover who had only recently finished withdrawing from the drugs he’d gotten hooked on after injuring his back some months earlier, and when he told us he had a truck and trailer, it was foolish not to find out exactly what he meant by a truck and trailer: I was thinking of the fourteen-footer I’d rented eight years before. But the mover’s truck turned out to be a pickup and his trailer one of those lattice-sided ones, like a playpen on wheels, that you use to transport a ride mower, and F.’s and my possessions made up not one load, but more than a dozen, not counting the additional loads we stuffed into our car. The move ended up taking two whole days—three, if you count the cleanup.

Late the first night, at around the time we were bringing up items from the basement, I decided to bury the ashes of my old tomcat. They were in the pantry, inside the handsome wooden box in which the vet had returned them after I’d had the poor guy put down the year before, a dazed skeleton who crapped in the tub and screamed to be fed a dozen times a day. The box had been included in the price of a premium cremation. I half expected F. to argue. It was late; Ching had been my cat, not hers, and she’d resented him for the way he’d joined Bitey in tormenting poor Tina, like a big oaf of a kid who allies himself with the class bully. But she’d been kind to him during his long decline, often kinder than I was, and she didn’t protest. It was too dark to bury him in the yard behind the house; that was where we’d interred Bitey’s ashes and Suki’s body, after she’d died three years before at the age of nineteen. By the light from the porch lamp, I started digging a hole beneath the maple on the front lawn, where he’d loved to lie. A proper grave for a cat, or for the ashes of one, would be about a foot square and three feet deep. It had been a dry summer, the earth was hard, and once I broke its surface, I encountered a web of roots that ran through the soil like rebar through concrete. I started one hole after another, moving farther and farther out until I was almost in the driveway, and every time I was thwarted by the same unyielding earth and roots that twanged beneath the shovel blade. From the car, F. called, “What’s wrong?” In my memory, it was “For God’s sake, what’s wrong?” and who could blame her, given that it was after eleven and I was cursing loudly across the street from houses where children slept? I told her to wait a minute. I said it again, and then several times more. I felt her impatience like the ticking of a bomb. But maybe what I was feeling was just the shame of fucking up another move, committing an entire household to a vehicle suitable for hauling sacks of horseshit. It was only by digging just at the foot of a tall, black hemlock like a tree in an Edward Gorey print that I was able to get down a foot, making what was less a hole in the ground than a notch. It was so dark here that F. had to come over and hold a flashlight so I could see where to pour the ashes. Even so, I ended up spilling a lot on the tree trunk and, I discovered later, on my jeans and work boots. “Good-bye, my sweet friend,” I told the old tom. “Be at peace.” But how could he be, when a portion of his substance was sprinkled on my clothing like the ash from a barbecue, to be rinsed off in the next wash?

In

Modern Painters, the critic John Ruskin identifies three ranks of perception:

The man who perceives rightly, because he does not feel, and to whom the primrose is very accurately the primrose, because he does not love it. Then, secondly, the man who perceives wrongly, because he feels, and to whom the primrose is anything else than a primrose: a star, or a sun, or a fairy’s shield, or a forsaken maiden. And then, lastly, there is the man who perceives rightly in spite of his feelings, and to whom the primrose is for ever nothing else than itself—a little flower apprehended in the very plain and leafy fact of it, whatever and how many soever the associations and passions may be that crowd around it.

I’m not that familiar with Ruskin’s work, but his categories seem sensible to me. This is not an adjective I’d associate with him, given the vinous extravagance of his prose and the weirdness of his personal life. In 1848, at the relatively advanced age of twenty-nine, Ruskin married Effie Gray. She was nineteen. Both of them were virgins.

He had been infatuated with her since meeting her two years before. The letters he wrote her during that time throb with longing, but also with what is pretty clearly sexual dread:

You are like a sweet forest of pleasant glades and whispering branches—where people wander on and on in its playing shadows they know not how far—and when they come near the centre of it, it is all cold and impenetrable. . . . You are like the bright—soft—swelling—lovely fields of a high glacier covered with fresh morning snow—which is lovely to the eye—and soft and winning on the foot—but beneath, there are winding clefts and dark places in its cold—cold ice—where men fall and rise not again.

Following the wedding ceremony at the home of the bride’s parents, the couple traveled by carriage to Blair Atholl in the Scottish highlands, where they were to spend the night.

What happened in the bedroom was later recorded by Ruskin’s lawyer, who made notes of what his client told him when he was contesting the annulment of his marriage. John and Effie changed into their nightclothes. He lifted her dress from her shoulders. He looked at her. Then he lowered her garment, and after a chaste embrace, they went to bed and slept uneventfully through the night. So they would sleep for the rest of their married life. He told her that he was against having children, who would interfere with his work and make it impossible for her to keep him company when he traveled abroad. There is no evidence as to whether Effie proposed another method of birth control, or knew of one. When she protested that chastity was unnatural, John reminded her that the saints had been celibate. And so she acquiesced, and the Ruskins’ marriage remained unconsummated until 1854, when she left him and filed for annulment, provoking a scandal almost as great as those that accompanied the later breakups of Prince Charles and Diana Spencer or John and Elizabeth Edwards. A significant difference was that public outrage fell on the reluctant—I suppose now you would say “withholding”—husband who had refused to give the wife her debitum. According to the notes taken by Ruskin’s lawyer, John told him that when he removed Effie’s dress, he was disappointed. Her body was not what he had imagined women’s bodies as being like. It was, he said, “not formed to excite passion.” In a letter to her parents, Effie put it less circumspectly: “The reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person.”

This is not at odds with Ruskin’s prior experience of female bodies, which was probably limited to the idealized forms of classical statuary, or to the fact that at the age of forty he would fall in love with a ten-year-old girl.

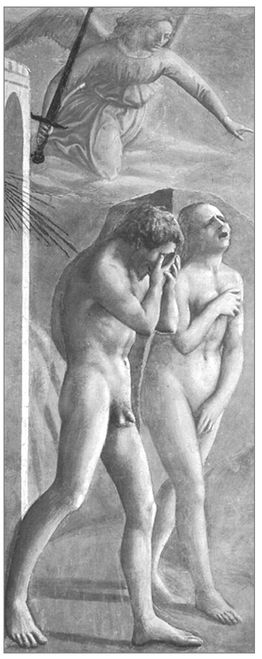

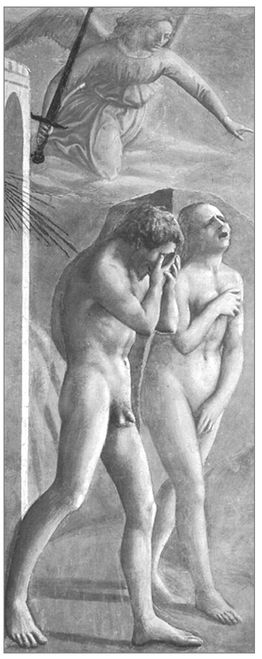

Ruskin admired Masaccio, especially his rendering of landscapes, but I find no reference in his writings to The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden. It would be interesting to know what he thought of the figure of Eve. Like other female images the critic was familiar with, Masaccio’s Eve has no pubic hair (one of Ruskin’s biographers speculates that it was this feature of Effie’s anatomy that caused him to drop her nightdress). Unlike them, she has the sexual characteristics of a mature woman. He might have viewed the painting as an allegory of his own wedding night: the man shielding his face in horror, the woman covering her swelling fields and winding cleft in shame. In this, he would have been hew-ing to the ancient scheme that classifies the genders as subject and object, viewer and viewed, knower and known.

Masaccio, The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from The Garden of Eden (1426–1428), Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine. Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

But in the story of the Fall, both Adam and Eve are active seekers of knowledge, Eve even more than Adam. Both are punished for knowing something they’re not supposed to know. It may be the narcotic sweetness of a fruit whose name has been lost to us; it may be the shudder of concupiscence; it may be good and evil, those words that meant nothing until suddenly they meant everything. Just for a moment, Genesis confers on the sexes an odd equality, which it then takes away when Adam is given dominion over his wife. At the same time, both Adam and Eve are objects of knowledge, members of the class of the known. It’s God who knows them, and it’s his gaze they try to hide from—at first so effectively that he calls out to them, “Where are you?” (Gen. 3:9). That a being who is supposed to be all seeing and all knowing must call, “Where are you?” to his creations is one of the story’s most resistant mysteries, and one of its most poignant. To me, God’s call is very poignant. It’s like a parent’s call to missing children. That, of course, is how many Christians read it, saying of the first couple not that they fell but that they strayed.

At once knower and known, the man and the woman are like people who look in a mirror for the first time and see themselves looking back. “And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they [were] naked.” (Gen. 3:7). To understand the vast gulf between the Greek and Hebrew worldviews, consider that Narcissus falls in love with his reflection and Adam and Eve recoil from theirs. But, then, they don’t see themselves in a pond, but in each other’s eyes. The eyeball is convex, and a convex mirror gives a distorted reflection. Maybe the first forbidden knowledge was how weak and uncomely they were in their nakedness, he with his drooping finger of prick and she with her lopsided tits and goosefleshed bum. Their eyes were as merciless as teenagers’. And perhaps their nakedness was more than a condition of the body, and what they saw were the wens and stretch marks of each other’s characters. Up until this moment, they hadn’t even had characters, being only another species of animal; it’s well known that no animal has a character until it is claimed by a human being. But now they had them. How lacking those characters were, how stunted and deficient! The man was easygoing, slothful, weak willed. The woman was greedy and shrill. And, really, she wasn’t bright either. She’d believed what a snake had told her. He saw her and was disgusted with her person. She looked at him and thought, “He is not formed to excite passion.”

I’d had the house painted before we moved in, so it looked cleaner. F.’s attic study was now trimmed in Mediterranean blue. But the closets were still filled with the landlord’s trash. The stove was broken and had a mouse nest inside it, and when we turned on the washing machine, it vomited gallons of hot water onto the floor of the barn. I got Rudy to buy a new stove and fix the washer, but by then F. had decided he was our enemy. The garbage might have been left as a taunt for her, as if Rudy had conferred with the vile old Broadway eminence who’d once accused her of dining on it. “Why don’t you say something to him?” she’d reproach me. It bothered her that I didn’t think he was our enemy. I’d remind her that I had said something; that was how we’d gotten the new stove. But whatever I’d said, I’d said mildly, making a joke out of what, even in the city, where landlords are permitted by law to seize your internal organs if you’re late paying the rent, would have been grounds for breaking the lease. I wanted Rudy to like me. Even now I’m embarrassed to admit it.

At least the cats enjoyed the house. It had been built in the 1850s—by a black freedman, according to Rudy, who prided himself on knowing the history of the valley—and then expanded with additions at either end, but it still had a long central aisle that was perfect for cats to scramble noisily up and down, especially late at night. Biscuit quickly staked a claim to the kitchen island. And all the cats liked roaming in the garden, with its lilac and apple trees, its beds of hosta, peonies, and day lilies in whose foliage small creatures nested, waiting to be killed. Out back there was a burrow occupied by a groundhog that looked like it must weigh thirty pounds. Once I saw it running—could Biscuit have had the nerve to chase it?—and thought I could feel the earth shake. Of all the cats, it was Gattino who seemed to be having the best time. He’d scuttle fearlessly up the smooth trunk of the horse chestnut that grew in the front yard and out onto branches fifteen feet above the ground, from where he surveyed the garden with a seigneurial air. “Gat-tini!” F. would trill to him, and he’d streak back down, half climbing, half leaping, and let her take him in her arms. I’ve always thought that a test of a cat’s personality is whether it enjoys this and, if not, how long it will put up with it. Bitey resisted being picked up with every claw and fang. Biscuit protested at first but could be jollied into lying still for ten seconds or so. Gattino liked it. You could carry him around like a baby.

For the most part, he got along with the other cats. It helped that he was still young. He and Biscuit used to wage mock battles, darting and rearing, he on his long legs and she on her short ones. But by now she was a full-grown cat, almost middle-aged. She lacked Gattino’s energy and appetite for play, and there were times you could see her wearying of being pounced on when she was trying to get a drink of water or having him dive at her food bowl, not to eat but to bat bits of kibble around the floor. She’d done the same when she was a kitten, but she had put away kittenish things and knew not to play with her food any more. If I were nearby, I’d clap my hands to make him leave her alone. Once I blocked him roughly with my foot and locked him in my bedroom until Biscuit could finish eating. When I let him out fifteen minutes later, his high spirits were intact and he appeared to bear me no ill will, but I find it significant that I didn’t tell F. about it.

One moment from that autumn stays with me. I was in the living room, listening to a CD I’d put on the stereo, Joni Mitchell’s Ladies of the Canyon. I hadn’t listened to it in years and was a little surprised to realize I had it, or any of her albums, on CD. She seems so much an artist of vinyl; her voice, which you remember for its birdlike high notes but which has an unexpected deep end, needs physical grooves to rise out of, and only records have those. “Woodstock” came on, and suddenly my eyes were filled with tears. I walked into the kitchen. I didn’t want the song to stop, but I needed distance from it. “What’s wrong?” F. asked. I gestured helplessly at the speakers. “I don’t know. It’s beautiful, it’s sad.” And then, “I want to get back to the garden.” I meant to say it jokingly, but my voice broke. F. started crying. “I do too.” We held each other.

Early that November, I spent a day working in the city. When I came back that night, Gattino was gone. F. had gone out to visit some friends; the cats had been in the garden. She’d considered calling him in, but she would only be away a little while, and it was still light. When she returned, the other cats were waiting by the back door. Gattino was nowhere in sight. That had been five hours ago. I told her it was too early to worry. The cats often stayed out late. We went out into the yard and called his name under the moon. I thought the problem might be that he hadn’t heard F.—her voice is soft—and I half expected him to come running in response to my manly bellow, hungry, his eye alight. It would be another thing I fixed, like F.’s laptop or the furnace that stopped putting out heat until I pushed its red reset button, which I knew how to do because of the instructions printed underneath. Of course I was forgetting the time I’d tried bleeding the radiator in my old loft. “GATTINO!” I yelled. “GATTINO!” My voice hung in the chill air. He didn’t come.

The next day I called his name up and down the road that ran behind our house. It belonged to the college next door and filed past dormitories, woods, and a theater before emptying at length into a parking lot. Once, back in the summer, when I was clearing ailanthus from the garden, I’d looked up and seen a young woman walking down that road, bare breasted and martially erect, then turn and vanish into the dorm behind us. I imagine she was doing it on a dare. The few cars that passed now were traveling slowly, and I was reassured by the thought that if Gattino had wandered off this way, he was probably safe. I don’t remember if it was that night or the next that F. looked across Avondale Road, which ran past our front door, and realized, with a start of sick fear, that neither of us had thought of searching in that direction. In the few months Gattino had been going out, we’d always shooed him back from Avondale because there was so much traffic there and it moved so fast. Many years before, not a hundred feet from the house, a car had struck and killed a little girl who was crossing on her way to nursery school. The school was now named after her.

We searched farther and farther from the house, along back roads and footpaths, in people’s yards and in a sinister abandoned barn that was always ten degrees colder than it was outside, like a morgue. We put up posters. We stuffed flyers in mailboxes and taped them to the doors of the college dorms:

At night we set traps and in the morning released the irate strays we found inside, each crouched beside an empty can of Friskies like a dragon guarding its hoard. Sometimes we speculated about how long it must take the captives to get over their initial panic and start eating. It was F. who organized us. Her earlier vagueness might have been a disguise that she had now cast off. But, really, she’d gone through most of her life alone and unaided, with her head down, applying herself to the business of survival. I’d just forgotten that. She had us call every animal shelter within fifty miles. She posted Gattino’s picture on animal-finder websites. She consulted psychics. At first only F. did this, since she believes in psychics, or half believes in them, but when one of them told her that she was sensing Gattino near a body of moving water, it was me who burned rubber to the creek a half mile away to pace its banks with an open container of cat food. I came back day after day. It didn’t matter what I believed. Once, I called a psychic myself, though she described herself—kind of sniffily—as an “animal communicator.” She told me that Gattino was dead, which I reported to F. She told me something else that I did not report: that he was a reincarnation of F.’s father, who had come back to show her how to “let go.” I still think it was a good idea to keep this to myself.

Most of the psychics told us our cat was dead. It was this that made me trust them. Somebody who wanted to rip us off would have told us that Gattino was alive and could be coaxed back if we burned some candles and left $500 in a shopping bag at the door of St. Sylvia’s. I might have done that if somebody had told me to; I might have rolled in a pile of shit on our front lawn. The one time I drew the line was when a half-literate stranger e-mailed F., having gotten her address from a shelter’s website, and told her that his friend Samuel had found Gattino and taken a fancy to him and brought him back with him to Cameroon. All we had to do was wire him the price of a plane ticket, and he’d send him home. I don’t remember whether we were supposed to pay for tickets for Samuel and Gattino or just Gattino, but “Cameroon” set off an alarm bell—so might “Belarus” or “Moldova” have done—and my misgivings were confirmed when we pasted it, along with the terms “Samuel” and “cat” into Google and found the outraged testimonies of people who had sent off the money and never seen their pets again.

In winter, we were still searching. Late at night we’d get a call from a security guard at the college who’d seen a one-eyed cat scrabbling in a dumpster. We’d throw coats on over our pajamas, drive fishtailing on the icy roads, and end up in a parking lot where a man in a down jacket shone his flashlight onto the snow. “He was just here.” We’d stand there stricken. The guard would go back to his rounds, and we’d put out a can of cat food—we spent a fortune on cat food that year—and sit in the car with the lights off, hoping that if we waited long enough, Gattino, if it was Gattino, might return. One night I caught a glimpse of a small, thin creature slinking under a parked car. It might have been a cat; it might have been a fox or a stoat. At any other time, I would have been thrilled to spot a wild animal near college dorms where kids from the city were smoking dope and reading Heidegger. But all I wanted to see was our cat. I wanted to bring him to F. like a treasure. I opened the door and stepped out slowly into the cold. I barely broke the membrane between stillness and motion. Many, many minutes later, I reached the car where the creature had hidden. I shone my light beneath it, then dropped into a crouch to see better. My knees hurt. How had I gotten so old? There was no sign of a cat.

Outside the airport it was cold, and the city’s garish carnival night was full of moving lights. Already I’d forgotten what it was like to be someplace that stayed bright after nightfall, apart from a two-block commercial strip where people went looking for action. No need to look for action here; it was everywhere, as in the interior of a spark chamber restlessly populated with subatomic fauna. Instead, you would have to look for stillness. You might not find it.

A bus took me downtown; a second one brought me across town to the railway station. I felt hopeful and eager. The feelings dimmed a little when I learned the next train wouldn’t be leaving for more than an hour. I had the impulse to call F. to tell her not to come pick me up. While waiting, I sat in a deli staring at the immense orange faces of two politicians, a man and a woman, who were debating on TV. Never had I seen teeth so huge or eyes so lambent. The volume was turned down and I was sitting too far away to read the captioning, so I focused on the debaters’ facial expressions. I might have been watching the actors in a silent movie, each holding up one or two big feelings for the audience to identify, approve of, and feel in turn. The man looked angry and, briefly, tearful. The woman, who for a pol was uncharacteristically attractive, even sexy, smiled and winked. The gesture—is a wink a gesture?—was so unexpected that I wondered if I was imagining it.

Who was she winking at? And was it a wink of flirtation or a signal that whatever she told her opponent shouldn’t be taken too seriously, she was just gaming Mr. Man, and we, the audience, were in on it? Was that why we should vote for her?

During those months we were looking for Gattino, our lives continued in some distant version. We both worked or tried to work. I screwed up a proofreading job so grotesquely that I offered to reorganize the client’s filing system for free, not because I hoped she’d rehire me—she would have had to be insane to do that—but because I wanted to feel less guilty. F. spent a lot of the time on the phone. She spoke with friends. She spoke with her sister, who she believed had psychic powers. She spoke with Wilfredo. She spoke with psychics. Sometimes she’d relay what the psychics had told her: Gattino had drunk some poisonous substance and died in agony. He’d died quietly, curling up into himself as if going to sleep. Once in a while, somebody told her that he was still alive.

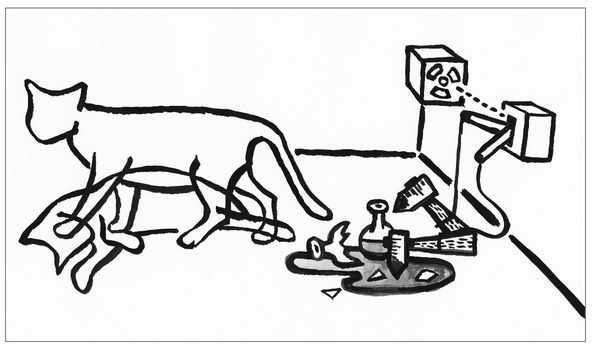

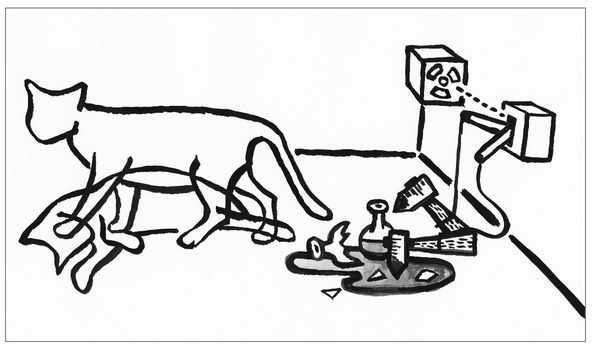

These possibilities seemed equally valid to me. I switched from one to the other with barely a cognitive jolt, and at times I seemed to hold them all in mind at once. Looking back, I’m reminded of the thought experiment of Schrödinger’s cat. The experiment is meant to illustrate the unpredictable and fundamentally unknowable behavior of particles on the quantum level. Any attempt to measure that behavior inevitably influences it. Until you look at the meter, you can’t know if a deflected electron has veered to the right or the left. Before then, you might as well speak of two ghostly electrons streaking in opposite directions or maybe a ghostly hybrid particle that moves in both directions at once. It’s only when you do the measurement that one of those phantoms evaporates and the other solidifies into a “real” particle occupying an identifiable point in space.

The physicist Erwin Schrödinger translated this paradox to the macro level. He proposed a scenario in which a cat is placed inside a steel chamber that also contains a tiny bit of a radioactive substance hooked up to a Geiger counter and a vial of cyanide. In the course of an hour, there’s a 50 percent probability that an atom of the isotope will decay. If it does, it sets off the Geiger counter, which releases a hammer that shatters the vial of cyanide and kills kitty. If the particle doesn’t decay, the cat remains alive. Schrödinger explained that one could visualize the system as “having in it the living and the dead cat (pardon the expression) mixed or smeared out in equal parts.”

As the diagram above suggests, the cat remains in this smeared, blurred state, equally alive and equally dead, until such time as an observer peers inside the chamber. The observer’s eye is what breaks the spell of indeterminacy. Perhaps our cat had become such a ghostly hybrid, not in a sealed box but in the wide world. Only when someone observed him would he solidify into life or death. For the observation to be reliable, however, it would have to be performed by someone who recognized Gattino, not as a generic cat searching for food in the cold and dark but as himself: this cat and no other. I suppose that means he would have to be observed by someone who loved him.

We were both sad, but F.’s grief was of a different order than mine. It admitted no other feeling. In my memory, she is always gazing out the window with sunken eyes. She is always walking out of the house with a sheaf of flyers that she leaves in the same mailboxes where she left some the month before, like a faithful mourner leaving flowers at a grave. My grief was more porous. At times I had the thought that we were making a huge deal about what was, after all, just a cat. I didn’t tell F. about this thought, which, even as I had it, felt petty, less indicative of moral discernment than of irritation at lost comforts. Maybe it was also about jealousy, though what could be more pathetic than a live man being jealous of a dead cat, or of a live cat and a dead one smeared out in equal parts? Maybe I wasn’t jealous so much as envious of the single-mindedness of my wife’s sorrow. Its purity was lyrical, a moment of loss extending to the farthest horizon. I could only grieve like a husband, pausing to call the oil company to schedule a delivery. It was winter, after all, and very cold, and when Rudy had told us that the heat would only cost $300 a month, he’d been full of shit.

On one of the first nights after Gattino’s disappearance, F. told me that she’d heard a voice in her head saying, “I’m scared.” Some time after that, the voice had returned. Now it said, “I’m lonely.” Late one afternoon about two months later, she told me she’d heard the voice again. It said, “I’m dying,” and then “good-bye.” When she told me this, I let out a groan. I sank to the floor. She’d looked into the chamber and shown me what was inside. We went into her bedroom and lay down together, holding each other, but some part of her felt far away. Maybe it was with Gattino. In retrospect, I can’t say how much of my grief was for our cat and how much was for F. So much of what I’d done during those months I’d done for her. It hadn’t helped. And, of course, much of that grief was probably for myself, and I clung to F. with what James Salter calls “the simple greed that makes one cling to a woman.”

That is from Light Years. A man’s wife has just walked out of the house in which they spent their marriage, and in that moment he is parted not just from her but from everything that had been his life. “A fatal space had opened, like that between a liner and the dock which is suddenly too wide to leap; everything is still present, visible, but it cannot be regained.”

The other cats seemed unaffected by Gattino’s disappearance, almost oblivious to it. Maybe Biscuit was relieved not to have him pestering her any more. In the mornings, she ate with serene concentration, chewing and swallowing, chewing and swallowing, not stopping until her dish was empty. F. said that when she’d come home that afternoon to find all the cats but Gattino waiting by the back door, Biscuit had looked especially happy.

When I think back to the time F. and I got teary eyed listening to “Woodstock,” I realize I’m not sure if it was before or after we lost our cat. I remember that it was a warm day, but that could have been soon after we moved in or the following spring. You can see what a difference that makes.