9

AFTER GATTINO WAS GONE, THE HOUSE, WHICH BEFORE had only irritated F., became hateful to her. We kept finding new things wrong with it. Ice and snow built up in a valley on the roof and, on melting, leaked into an interior wall so that the new paint ballooned in watery blisters like the marks of some loathsome skin disease. We discovered that the toilet was sinking into the bathroom floor—slowly, but with the threat that one day, when somebody sat down too heavily, it would plummet into the basement. I called Rudy to complain; he came over and made what repairs he could, but his presence made F. angrier. She’d stalk past him, tight-lipped, and lock herself in her room; then she’d be angry at me for talking to him. I’d be angry back.

“What do you want?” It seems to be the question I asked her more than any other. Only now does it occur to me what an odd question it is: F. and I had been together ten years, and you’d think that after all that time, I wouldn’t have to ask. “Do you want to move? We don’t have the money to move.” It was half true: I didn’t have the money. Perhaps I asked her if she wanted to leave, though it seems to me that given the ambiguity of the wording, I would have been afraid to.

“I don’t like being here,” she’d say, and in my memory she’d be looking not at the house or at Avondale Road, with its heedless, gnashing traffic, but at me.

The well-known symbolism of houses: The Professor’s House, The House of the Seven Gables, Bleak House, A Doll’s House, which Nora had to leave, each a metonymy for the lives that hum and gutter inside them. Swann’s house, where he lives with the deceitful Odette, whom he has made his wife now that he no longer loves her; the fashionable house of the Guermantes, where the duke humiliates the duchess in front of the dinner guests. The house of Charlus, who loves to be beaten; the house of the Verdurins, who love to climb; the house where Marcel imprisons Albertine, whom he thinks he loves. We speak of relationships, too, as contained spaces, sites of comfort or constriction. I’m in a relationship. I want out of this marriage. Really, I wasn’t sure I wanted to stay in it either. We didn’t even like the same kinds of food. Yet, at the same time, a small, shocked voice cried out inside me—but you promised! The cry of a child in a car racing past the Dairy Queen.

On some level, I understood that F.’s anger was part of her grief. It was anger at a world that had been emptied of the thing she loved. I belonged to that world. At least I was familiar and intermittently comforting, and I had some understanding of what she was feeling. Other people had none. One evening we had dinner with a writer I’d met through friends. In the course of the meal, it emerged that he’d once considered buying our house, back when it was vacant. He asked F. if she liked living in it. Astonishingly, she said nothing about the sinking toilet or the garbage left in the closets. She said only that the house had been spoiled for her by a trauma. Then she told the writer how we’d lost Gattino. The whole time, he looked at her as if waiting for more. At last he asked, “So that was your trauma, was it?” He was English, and he may have had the English distaste for promiscuous displays of feeling, especially the false kind Americans are prone to. F. and I share that distaste, or used to share it. I could have vouched that her feelings were real, that I had them too, but it would have made both of us seem pathetic.

Anyway, the question he was really asking wasn’t about authenticity but appropriateness, which varies not only from culture to culture but from person to person. The writer’s wife was holding their small daughter. She was about a year old and charming as most children are at that age, looking about her with eyes full of light, grabbing things that her parents either deftly took away or let her hold as down payments on the world of objects that would one day be hers. At the time they were thinking of buying our house, did they know that a child had been killed crossing the road outside it? And if they had known, would they have bought it anyway?

The death of a child is said to be the most terrible of all losses. It’s one of the few our culture still pays deference to. Part of that has to do with biology, the fact that our children are a part of ourselves, the tendrils we cast forward into the future. And then, of course, a child is so small and helpless, eager, clumsy, so guileless or possessed of a guile so primitive that it fools no one, which is why we find it endearing. Once we carried our children in our arms; we washed their faces for them. When it was time to cross the street, we held their hands. Even parents whose children are long grown up remember doing that; I can remember doing it for my friends’ children when they were small. I remember doing it for Wilfredo. Farther down the scale of grief is the loss of a wife or husband, a brother or sister, and after that the death of parents, which is taken almost for granted, since we’re supposed to outlive them. What’s the standard number of personal days companies give employees for the death of a parent? One, two days?

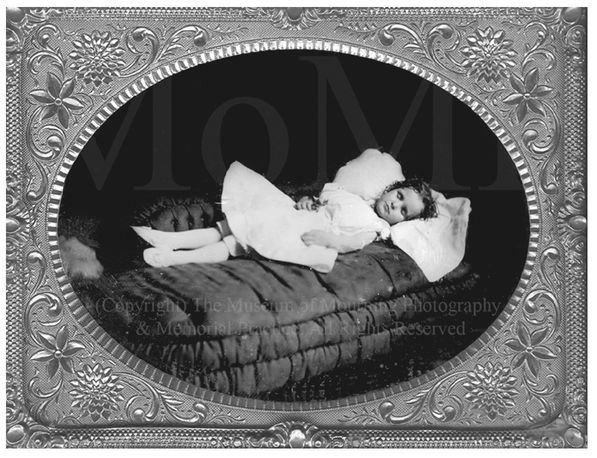

Yet the Victorians reckoned the loss of a husband as more dire than that of a child, at least judging by their dress codes. Widows were supposed to wear black crepe and full veil for two years. The first year, they wore the veil hanging over the face; the second, they were allowed to pin it back. Bereaved parents wore deep mourning for one year, after which they could transition to lighter fabrics in black, white, or gray. Widowers only had to mourn for a year. It pays to remember that Victorian women were completely dependent on their husbands, and the death of children was far more common that it is today. Hence the photographs of deceased children that were part of the decor of so many homes of the period. Often, the children are posed on the deathbed.

Copyright Museum of Mourning Photography and Memorial Practice, Oak Park, Illinois.

Where on the grief scale do you place a lost cat?

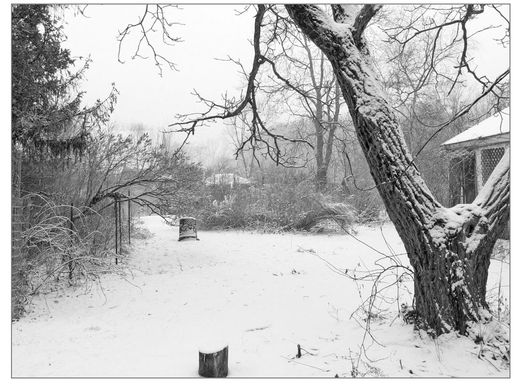

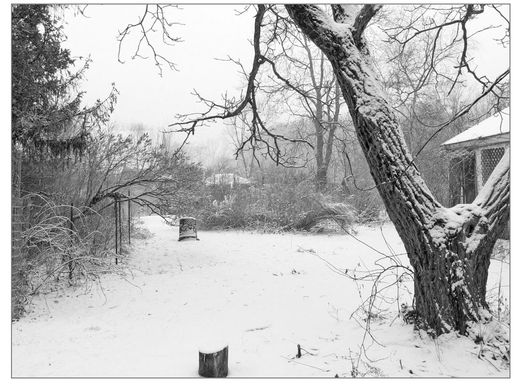

Considering what had happened to Gattino, it would have made sense to keep the other cats indoors. It was winter, so they didn’t want to go out much. Still, once or twice a day Biscuit would plant herself by the back door and, if you didn’t open it, start meowing and then tearing out her fur. Was it a spontaneous upwelling of frustration or Machiavellian blackmail, and if it was blackmail, how did she know it would work? It always did. I’d open the door; she’d step outside and turn to look back at me. I can’t say if the look was one of triumph or uncertainty; she may have wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to yank her back inside. Some days she’d bound out into the snowy garden, raising a small white explosion with each leap. At other times she was deliberate. You could tell by her paw prints. She’d step with care between the drifts and around the brittle stalks of last year’s flower beds. She’d pause to listen for the scrabbling of burrowing mice. She might inspect the perimeter of the groundhog burrow, but, wisely, she didn’t go inside it. Sometimes she climbed the plastic children’s slide that Rudy had bought for his son when he was little and took up a perch at its summit, from which she could look out at the white garden and the deer-eaten hedges that screened it from the road but would pose no obstacle to a cat that wanted to go out in pursuit of a scent or a flash of movement. Cats are cautious animals, but they are animals, and certain things summon them irresistibly. They don’t even try to resist them. They just go.

Maybe F. and I were weak or lazy, unable to resist our cats any more than they could resist the sight of a rabbit hopping across the road. But when we talked about it, we agreed that going outside made them happy—not in the panting, theatrical manner of dogs but quietly, intently, with no need to proclaim their well-being to onlookers. Going out was how they fulfilled their nature, inasmuch as we have any sense of what that nature might be. Cats are the creatures that domesticated themselves. They chose to come to us, knowing that we were where the food was. Unlike dogs, they may never have understood they were doing us a service. We just didn’t stop them from killing rats. Humans trained dogs to do what we wanted, though the argument can be made that they trained us. We allowed cats to do what they were already inclined to do. For a long time, people fed them only intermittently, believing they could get by on vermin. (In 1837, a French writer cautioned that “the cat who is not given food is feeble and malingering; as soon as he has bitten into a mouse, he lies down to rest and sleep; while well fed, he is wide awake and satisfies his natural taste in chasing all that belongs to the rat family.”) And in contrast to the vigilance and rigor involved in house training a dog, a cat has only to be shown the litter box, though it falls to its owners to scoop out the turds. Our relationship with cats is about care and affection, but it is also in a very deep way about permission. We must let them be what they are. It’s not as if we can stop them.

But one of our cats—the smallest and most vulnerable one, the one F. loved the most—had gone off and never come back. Maybe he’d gone off to fulfill his nature; maybe he’d died in one of the awful ways the psychics had laid out for us: convulsing from poison or broken in the jaws of a coyote or slowly freezing in the shadows of the wood. Before he died, he might have been hungry and afraid. He might have been lonely, a feeling he would never have known if humans hadn’t taken him in and fed him on the bitter milk of their love. F. thought a cat would understand death, even a young cat like Gattino, and she pointed to the brisk way the cats she knew had dealt with one that was dying, sniffing it once, then turning away. But then she remembered her old gray tabby weeping on the night Bitey died: in memory, the liquid in her eyes had become tears.

To truly let the thing you love be what it is means surrendering it, perhaps even to death.

In the midst of this, I was going broke; it was one of the things we fought about. We fought more or less politely, without yelling, without even getting that angry, until one or the other of us left the room, ostensibly to do something. The other one didn’t follow. That spring, I was offered a yearlong teaching job in North Carolina, and I took it. F. would stay up north with the cats; I’d send her money for rent and utilities. We’d visit each other when we could. When you factored in the second rent, I’d actually be losing money, but I couldn’t afford not to go. I was losing money where I was, mired in my torpor, teaching one day a week and selling about one magazine article a year, and at least we’d have medical insurance. F. was afraid of being alone in the house. Briefly, she threatened to get a gun. I managed to talk her out of it. She’s not good with tools or machines, and the likely outcome was that she’d shoot herself in the foot or plug Rudy some morning when he came over to chip ice from the roof. I could see her telling the cops she’d thought he was a prowler.

A temporary solution came when she was invited to a residency in Italy. I was happy for her but also envious, and I felt a little peeved at not even getting a proper chance to leave her. I wanted her to pine for me. Instead, shortly after I started teaching, my wife would be flying to Rome, then motoring up north to spend a month being plied with Prosecco, prosciutto, and figs under the cypress trees. I worried that it might make her sad to be so close to where she’d found Gattino. She said it wouldn’t: nothing could make her sadder than she already was. She said it defiantly, as if I were the one who’d asked her, “So that’s your trauma?” Eight months had passed since our cat had disappeared: she was still wearing the black veil, and she was wearing it over her face.

But who was going to care for the cats? I couldn’t take them down to North Carolina with me; my landlords there were allergic, and, anyway, I could think of few things more distressing for a cat than to be driven twelve hours in a crate and then cooped up for a year in a house full of strange, unclawable furniture. I could think of few things more distressing for a person than to be the one who drove three of them. We had to get a cat-sitter, not a once-a-day drop by but someone who’d stay in the house. Bruno was the child of friends, a big, strapping kid, raised on the Lower East Side back when it was a habitation of schizophrenics and junkies. He’d gone to the college next door and was still hanging around the neighborhood the way a lot of its graduates did, knowing that never again would they find a place where they and their ideas were taken so seriously. I flew back from North Carolina to show him around the house, which he clearly loved and was prepared to spend quality time in. He didn’t just come with suitcases but with keyboard instruments and a Mac G4 whose monitor was bigger than our TV set and what appeared to be a month’s worth of fancy groceries. He wasn’t put off when I told him to be careful sitting down on the pot. But he seemed leery of the cats. When I warned him that they might jump up on the table while he was eating and try to get at his food, his eyes widened in alarm.

“What am I supposed to do then?”

“You pick them up and put them down on the floor.”

“They’ll let me pick them up?”

I wanted to ask F. if she thought we were making a mistake, but by the time this conversation took place, she was on her way to Europe. Still, I e-mailed her what I told Bruno, figuring she’d appreciate it:

“I doubt they’ll be in a position to stop you.”

Once or twice a week, on a schedule we set up by e-mail, F. and I would Skype each other. In theory, it was more intimate than the phone, more like being together in the same place instead of calling out to each other from across an ocean. But really, it felt more remote. I couldn’t walk around the house with the phone pressed to my ear, peeling a cucumber at the sink or portioning cat food into three dishes; I had to sit at my desk, as if I were working. My wife’s face smiling uncertainly out of a letterbox on my laptop screen made me think of software. You clicked on the icon, and she came jerkily alive. She was so small, and the room behind her was such a generic room, veiled in shadow with a European light fixture on the ceiling. I’d ask her what the weather was like there. After a pause—I doubt I’d ever asked her about the weather the whole time we’d been together—she’d tell me. Then she’d ask me what it was like where I was. This was the future that had been foreseen for us when we were kids, by comic books and science fiction movies with F/X crude as a cardboard robot. We had arrived there, and nobody had told us. I don’t remember what we talked about. We weren’t nearly as expressive as we were in our e-mails, which were still full of gossip and humor and, sometimes, tenderness. The technology that made us present to each other was too intrusive, the lag between words and the moving lips that uttered them, the way her face kept freezing or shattering into a cascade of pixels. Never had I been so conscious of seeing another person. After a while, we just made faces at each other. It was more fun.

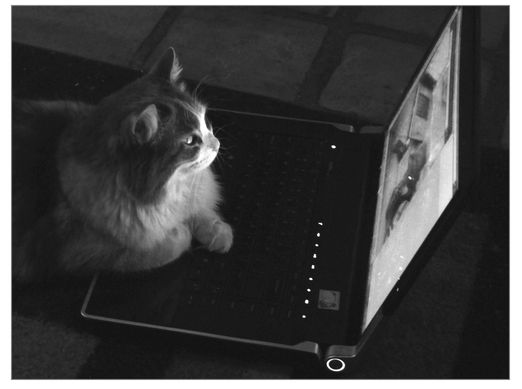

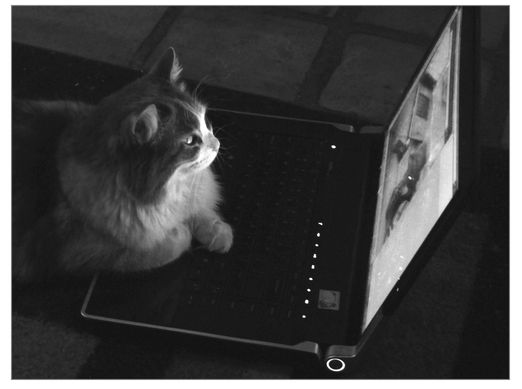

As further evidence of Skype’s inadequacy, I was once using it to talk with my twin nieces in Chicago when they asked to see Biscuit. She was right nearby so I lifted her into my lap and held her up to the webcam, and while the girls squealed with pleasure (God knows why, since they had cats of their own, big fat ones twice the size of any of mine), Biscuit was uninterested. She didn’t even sniff the screen the way she would a telephone that voices were coming out of. Stoically, she sat on my lap, squirming only a little. It was one more thing I was subjecting her to. You could chalk this up to a cat’s poor depth of visual field or to the fact that the squeaking figures on the screen had no smell (only now does it occur to me that on video feed, the girls were about the size of mice). Or you can ascribe it to an innate refinement of perception that allows a cat to distinguish between a being in the world—what Heidegger calls Dasein—and a being reconstituted in cyberspace and to ignore the one in cyberspace, which has nothing nice to give her.

Maybe what I felt when F. and I Skyped was the anxiety that arises from sensing the disjunction between those beings. Intellectually, yes, I understood that what I was seeing on the screen was in fact F., or the light that had bounced off her in her room in Italy and then been captured by a webcam, digitized, and transmitted over the Internet as packets of data, just as what I was hearing was a digital transcription of her actual voice. I didn’t think it was a special effect, though within my lifetime we may reach the point where we can no longer tell an actual person on the screen from a complex animation of that person, maybe stitched together from the billions of digital photo and video and audio samples that have been taken of her in her lifetime, the ones she posed for, the ones snatched on the sly by surveillance cameras in banks, airports, office buildings, and subway stations, not to mention the cameras that gaze impassively down on our streets, waiting for someone to bite into the vouchsafed fruit and look up with juice shining on her lips.

But the F. that I was seeing and talking with was a mediated F., an F. that had been mediated over and over. Between the image on my screen and the woman in a room in Umbria lay an uncounted number of operations, as if a gold coin of great worth had been changed into one currency after another by a series of invisible money changers, one of whom eventually gave me what he said was a sum equivalent to the value of the coin. I guess it was in dollars. But what were the transaction fees? At those moments when F.’s voice didn’t sync with the movements of her lips, what was she really saying? When her lively, changeable features were replaced by a Mondrian schematic that might be the universal skeleton of digital beings, what expression was being hidden from me? On seeing her face appear on my screen, I felt the pleasure I always felt on seeing her after some time apart, but how much of that pleasure was borrowed from memory? And if my memory had been as limited or, say, as capricious as Biscuit’s, would I have looked at F. with the same incomprehension, seeing only a tiny, smiling figure in a window the size of a credit card, with a piping voice that was almost familiar?

When we speak of love, we must speak not only of desire but delight. Desire doesn’t last very long—typically, no more than three years. Delight doesn’t always last longer than that, but it can. Studies have yet to identify its upward limit. Delight is not a condition of lack but of sufficiency, a plenty wholly independent of the circumstance of possession. You don’t have to possess the object of love to delight in it, any more than you have to possess the sun to bake voluptuously in its warmth. You can revel in the object from afar, regardless of whether she loves you back or is even aware of you crouching in your blind, camouflaged in your cloak of reeds. Just watching her is enough. I don’t desire Biscuit; I’m relieved to say I never have. But thinking of her, I visualize her busy gait, the purposeful mast of her tail, her trills and chirps of greeting. I recall the way she rubs her jowls against mine, the way she rolls onto her side and pumps her hind legs to tear the guts out of an imaginary enemy, and I’m filled with pleasure. A similar pleasure comes over me when I think of F. Her high, round forehead, which seen in profile—say, on those afternoons she used to walk down Astor Road beside me—looks as innocent and intrepid as Mighty Mouse’s. Her silent, pop-eyed grimace of mock frustration. The little grunt with which she settles into herself as she gets ready for sleep. Her Midwestern reticence and her heedless blurtings. The look of undisguised appetite she casts at a stranger’s entrée in a restaurant, as if at any moment she might reach over and help herself to a forkful of it.

These details seem to reflect something pure and unselfconscious in the object, the object as she is when she thinks no one is looking. When I see my cat or my wife, I seem to be seeing her as she truly is, free of all my wonderful, occluding ideas about her, including (in F.’s case but not Biscuit’s) the wonderful, occluding idea of desire. There’s a Zen koan that asks, What was your original face before you were born? Perhaps what I am delighting in are those unborn faces, the woman’s, the cat’s. And perhaps this pleasure, so generous and self-renewing, allows us to participate, even at a remove, in what God may have felt as he looked down at his creation and became lost in its splendor, maybe to such a degree that for a time he forgot that he created it, that it was his.

In the foregoing, of course, the words “see” and “seeing” are used figuratively as well as literally. It’s possible to delight in the love object even when one cannot actually see her, as, for example, when one is separated from the object by time or distance. Under such circumstances, one must be content with the images afforded by other faculties. One must imagine the object as she might be. One must remember her as she was.

Bruno didn’t return phone calls with the promptness one values in a cat-sitter. The first week he was at the house, I had to leave four or five messages before he called back to tell me—wearily—that the cats were fine. When we Skyped, I told F. I was beginning to think the kid was a lox. As if he’d overheard this and resolved to make a better impression, the next week he called me on a Monday evening, before I’d even begun to pester him. But when his name came up on my caller ID, I felt a twinge of unease, and the moment I heard his voice, my whole being constricted like a single great muscle in spasm.