If run correctly, meetings can be quite productive. They can help formulate and implement an organization’s policy, and they can provide forums to discuss and resolve issues. Unfortunately, too many meetings lack focus and fail to achieve any meaningful purpose. And in most organizations, there are simply too many meetings, and they last too long. As a result, there’s less time to get work done. Meetings reportedly take up approximately 35 percent of the workday for middle managers1 and up to 60 percent of the day for top executives.2

When I was president of Fidelity Investments, I could easily have spent every hour of every day at meetings. Everyone wanted to talk to me about their problems and plans. They included the members of my management team, the top executives from the various marketing divisions, the risk and compliance functions, and the system development units, as well as outside officials from government bodies and service providers. At the same time, I wanted to meet regularly with the significant players in our investment group and our key institutional clients.

In order to satisfy the demand for meetings within my available hours, I refused many meetings and dealt with certain matters through emails, memos, or phone chats. Today, before I call any meeting, I carefully think about what I want to get out of it. If I’m not satisfied with my answer, I don’t go forward with the meeting.

There are two main reasons to have a meeting. First, you should call a meeting if you need to establish a personal relationship with someone outside your organization, such as an elected official or new customer. Second, meetings are often necessary if you want to engage people in a debate; face-to-face dialogue cannot be replaced by email or phone calls.

When managers face a tough challenge, they often call a “brainstorming” meeting. They bring in a broad swath of employees and solicit ideas on how to resolve the problem, without worrying for the moment whether ideas are good or bad. According to the theory, one person’s suggestion may inspire someone else to put forward another idea, so it’s useful to bring people together for this purpose. However, research has found that simply shouting out the first thing that comes to mind is not an effective way of generating ideas. To have an effective brainstorming session, this research concluded that you must be willing to criticize the suggestions put forward.3 This helps shape the discussion and turn raw ideas into workable proposals.

By contrast, many meetings are called simply to share information, rather than debate or discuss it. Such meetings tend to be unnecessary; usually you can accomplish this just as well via email in a fraction of the time. For example, the group at Fidelity responsible for preparing board materials wanted me to meet with it for two hours each month to review the materials. Instead, I asked them to email me the materials, along with a cover email highlighting the key issues. I then sent my comments by email to the board group. Although reviewing the material and writing the email took some time, it invariably took less than the two hours or more that I (and they) would have spent at the meeting.

Similarly, you should not call a meeting simply because “it has always been there.” At the beginning of the year, the boss may schedule a meeting every Monday to go over plans for the next week. Some weeks, the meetings may be necessary—but the boss should decide every week whether the meeting is actually needed.

Last, many in-person meetings are unnecessary in light of recent developments in videoconferencing. I used to be very put off by the regular delays in transmitting speech over video. But last year, when my two-hour flight to Minneapolis was canceled at the last minute, I was forced to hold a videoconference instead of an in-person meeting. Wow! The picture was vivid, and the voices transmitted instantaneously. My colleagues in Minneapolis agreed that I had no reason to make similar trips in the future. It’s unproductive to spend hours on air travel to meet in person when you already know the other attendees and have access to top-quality videoconferencing.

For meetings that are necessary, try to limit invitations to those who truly need to attend, thus allowing as many people as possible to avoid the meeting. In the past, I have participated in many meetings of fifteen or twenty people. That number is far too big to get anything done. Various researchers have arrived at different conclusions as to the optimal meeting size,4 but they would all agree that a meeting of seven or eight people is better than a meeting of fifteen or twenty.

Another technique for reducing the number of meetings is to ban meetings one day each month. This allows you (and any employees you manage) to catch up on work that you have been putting off in order to attend meetings. It also shows you and your employees how much work they can get accomplished without meetings. At MFS Investment Management, we instituted a policy that meetings were forbidden on the first Friday of every month.

Nevertheless, despite all attempts to reduce the number of meetings, you will be invited to meetings that seem likely to be unproductive. How can you avoid those meetings? Just say no! You can politely explain that you are too busy, have deadlines to meet, or have too much scheduled on that day.

As a busy executive, I decline many external requests by directing them to more appropriate employees in my organization. A lot of external firms want to meet with me to discuss supplying services to my firm. I refer them to the appropriate division, such as an advertising firm to the marketing division and a software firm to the systems unit. Many charities request meetings with me to request a donation. Although they may be pursuing worthwhile goals, I politely refer them to an employee responsible for vetting corporate contributions.

Declining invitations for internal meetings may require a little more tact. Politely emphasize to your colleague that the reason for saying no has nothing to do with the content of the event—or the person making the request—and everything to do with your crammed schedule. Be clear that you would like to attend such a meeting, and express regret about the conflict. For example, if a response by email is appropriate, you can reply as follows: “I am pleased that you invited me to the meeting on developing best practices for internal audits. I am a huge believer in improving the risk management of our firm. However, I must be preparing for client presentations the next day, so I will unfortunately be unable to attend. Thanks again for the invitation.”

What if the meeting is being hosted by your boss? Those requests are harder to avoid. However, if you and your boss trust each other, you should describe your situation and ask for a reprieve from your boss. In other words, negotiate! You might explain that you have several deadlines to meet and ask which items should be delayed or deleted due to attending the meetings—for instance, “I can attend this meeting, but is it okay if I complete my assigned report on Wednesday instead of tomorrow?” Either your boss will get the point and allow you to skip the meeting (or leave after the first hour), or he or she will reschedule your other work commitments.

As any professional can tell you, many meetings run too long. For instance, a colleague told me of a four-hour meeting that was dominated by two employees arguing about what section should appear first in an internal planning document! The discussion probably cost their firm several thousand dollars: their employees were getting paid, but little work was getting done. Most meetings can be completed effectively within sixty minutes, and meetings really should never run longer than ninety minutes. After meeting for an hour and a half, most participants become too tired, bored, or impatient to engage productively.

No matter how worthwhile the topic may be, lengthy meetings are unproductive because of how people pay attention—and how they don’t. Back in the 1970s, two researchers attended more than ninety college lectures and observed when students were focusing and when they had lapses.5 They noticed that students paid attention to the professor and studiously took notes for the first ten to eighteen minutes of lecture. At that point, the students’ attention would lapse: they would look at the clock, stare blankly into space, or even doze off briefly. After a brief lapse, they would refocus on the lecture. However, as the lecture continued, the lapses occurred more frequently as the students found it harder and harder to pay attention. By the end of the fifty-minute lecture, they were paying attention for only three to four minutes at a time before their attention wandered.

Given their maturity and training, I’d like to think that professionals are better able than college students to maintain focus. But the basic principle holds: attention is most concentrated at the beginning of a meeting and then gradually declines.

One way to keep a meeting to ninety minutes is simple: schedule it for ninety minutes. If you schedule a meeting for two or three hours, that is how long it will take. If you schedule a meeting for one hour on the same subject, it will still finish on schedule. As Saul Kaplan, the founder of the Business Innovation Factory, put it, “Meetings are like a gas expanding to fill all available space.” Cabletron, a cable TV company in New Hampshire, takes a more radical approach: it bans chairs in its meeting room. With everyone standing, it’s easy to enforce the company’s thirty-minute limit on meetings.6

Off-site meetings for all employees in a division or department tend to have a similar problem: although they may build team spirit and allow for in-depth discussion, they often last too long. In my experience, an off-site meeting can be done well in one day at a local hotel or college. If participants come from across the country, two days may be needed for an effective off-site because of travel logistics. Moreover, if employees travel from around the world, it is useful to surround a two-day off-site with other meetings involving those travelers. But an off-site of three or four days usually involves a significant waste of time.

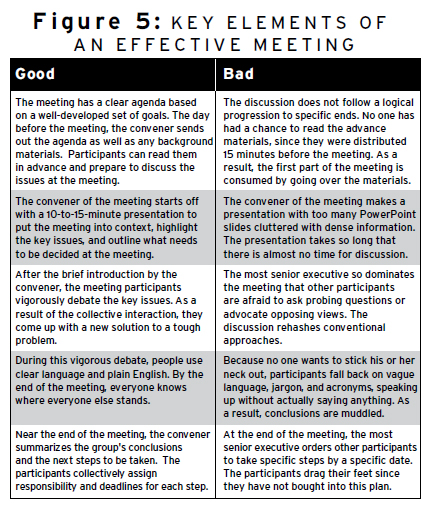

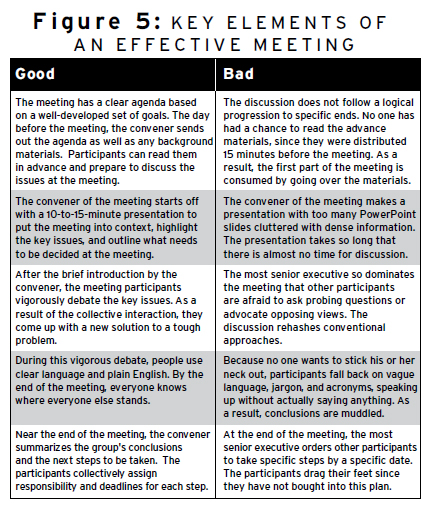

After working hard to shorten, eliminate, or avoid meetings, you should then maximize the productivity of the few meetings that you do need to attend. Take a look at figure 5 below to learn about the five main elements of an effective meeting, along with what can go wrong when these elements are absent.

Agenda and Advance Materials

How can you have meetings with more good than bad features? To begin with, every meeting needs an agenda, preferably one that spells out its purpose. Most meetings also need some background materials so everyone has a common information base. If the meeting is being run by your boss—and he or she tends to forget this step—you could volunteer to draft the advance materials yourself. This will make the meeting run more smoothly, and you will ingratiate yourself to your boss at the same time.

If the meeting is being run by a peer, you should make your attendance of the meeting conditional on receiving the agenda and the advance materials at least a day before the meeting. If the agenda and materials do not arrive or show up at the last minute, don’t go to the meeting.

Introductory Presentations

If there are no advance materials—or if participants do not have the time to read them—the convener will have to make extensive opening remarks describing the issues in detail. I have often been in meetings where the presenter starts to go through a large number of PowerPoint slides, literally reading every word on every slide. This reflects intellectual laziness—the presenter is passively transferring information from his research to his audience without distilling it. Making complicated information more concise is part of the presenter’s job.

Even useful presentations become boring if they last too long. Just like students at a college lecture, employees won’t be able to pay attention for more than twenty minutes. In order to hold their attention beyond that point, the mode of the meeting should change from a presentation to a discussion. Such a change in the middle of the meeting effectively “resets” people’s attention clock, helping them refocus on the subject under discussion.7

What should you do, then, when the leader of the meeting ignores this advice and keeps plowing through PowerPoint slides, even when the group has a solid understanding of the issues at hand? This requires some diplomacy. As the leader of the meeting, I usually make a polite remark after the initial fifteen to twenty minutes, such as “You’ve made some really interesting points, so please make sure that we all have enough time to discuss them.” If the presenter does not get the hint, I might become more pointed: “Perhaps you could finish up in a few minutes, so we could begin the discussion.” If the presenter still persists with a robotic march through PowerPoints, I often find myself tempted to take a cue from an old movie and start yelling, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!”8

In April 2010, newspapers such as the New York Times, the Daily Mail, and the Guardian reported on a particularly complicated PowerPoint slide. The slide, presented to U.S. generals in Afghanistan, depicted a dense flowchart tracing how each of 119 factors, such as “Perception of Coalition Intent & Commitment” and “Ins. Provision Of Gov’t & Services,” affected one another. At the time, General Stanley McChrystal, then the commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, quipped, “When we understand that slide, we’ll have won the war.”9

I had intended to include a copy of the slide in this book. However, its creators, a consulting firm, declined to give me the rights to reprint it. Although the slide has been widely published, their email claimed that “client confidentiality agreements” prevented them from letting me reprint the image. So if you want to take a look at the slide, you’ll have to find it yourself. That shouldn’t be too hard—you might type “Afghanistan PowerPoint” into a search engine.

Sometimes, however, long-winded presentations are not the leader’s fault. The leader of the meeting may have done everything right—he or she sent out advanced materials and is prepared to enter into vigorous debate. But everyone else in the room hasn’t fulfilled their end of the bargain by reading the advance materials. So the leader finds it necessary to make a longer opening presentation than he or she had planned.

If this happens to you when you’re leading a meeting, strategically call your colleagues’ bluff. Proceed on the assumption that the advance materials have been read, and begin a debate after a few introductory remarks. This will doom the present meeting to failure (so maybe you should pick a meeting that’s not crucial). But you can bet that before the next meeting, the other participants will do their homework.

Promoting Vigorous Debate

The potential domination of a meeting by the most senior executive is a complex problem. Most bosses underestimate the huge impact of any opinion they express to their employees. I was at a meeting with Ned Johnson, the chairman of Fidelity, when he made an offhand remark about the location of a large tree near a company office. Within three days, the tree was moved several hundred yards at a cost of more than $200,000. When Ned heard the cost, he was dumbfounded that his remark had been interpreted as a command.

On the other hand, a boss has to keep the meeting on track. An unstructured and leaderless meeting is likely to be chaotic and unproductive. In leading a meeting, you should follow the agenda and encourage everyone to talk.

That’s why again I use the rebuttable hypothesis (see chapter 2, “Focus on the Final Product”) to reach a proper balance: it allows the boss to focus the meeting without dominating it. I might say, “Here is the area where we need to do something. But it is a difficult area, and there are several ways to address this problem. Now, this is my tentative view on the approach we should take, but I could be wrong. I want you to feel free to disagree and offer alternatives.” Then I have to hold up my end of the bargain: I have to be willing to discard or modify my hypothesis if someone comes up with a better idea.

In certain cultures, however, you should recognize that subordinates will be extremely reluctant to disagree with any proposal made by a senior official. To get the discussion started, you could arrange in advance for someone to lead off the debate. Or you could go around the table and ask everyone to question one aspect of the proposal.

Even in the United States, I recommend that you appoint someone in every meeting to play devil’s advocate. That person’s job is to argue against what is being proposed by emphasizing the negatives, such as tough competitors or regulatory hurdles. In that manner, the meeting avoids the problem of “in-house baseball,” where everyone agrees on a proposal without careful analyses of the counterarguments. I’ve attended too many meetings that proceeded as if the firm faced no serious competitors or resource constraints.10

We’ve all been to meetings where two chatterers distract everyone else by having an annoying side conversation. As the leader of a meeting, don’t be afraid to call out your colleagues. In most cases, it’s enough to shoot the offenders a quick glare—knowing that they’ve been caught, they usually end their side conversation. If you can’t catch their attention, discreetly pass them a short written note: “Your conversation is distracting everyone else.” If they still don’t get the message, stop the meeting and politely ask that everyone give the meeting their full attention.

Similarly, I consider a ringing cell phone to be a serious offense. It is disruptive, not to mention quite embarrassing to the owner—especially if the ringtone is a lively Top 40 hit. So before starting every meeting, ask people to put their phone on vibrate. If someone is expecting a really important call that truly can’t be missed, he or she can leave the meeting room when the phone vibrates.

Using Plain Language

Many meetings are unproductive because participants use a lot of jargon that obscures the real issues. Quite often, people use buzzwords as fallbacks—making it sound as though they have something substantive to say when they actually don’t.

For instance, consider the word “synergy.” In making presentations to investors, many CEOs try to justify a proposed merger or acquisition by saying it is “synergistic” or that the combination will result in “synergies.” When professional investors hear any version of this magic word, they usually sell the stock. Why? Because if the CEO had a good reason for the merger, such as reducing costs or acquiring patents, he or she would have said so. By invoking “synergies,” the CEO is signaling that he or she does not have a clear reason for doing the deal and is just trying to put a positive spin on a poorly understood transaction.

Another vacuous phrase that I try to eliminate is “think outside the box.” Roughly speaking, this phrase is a general exhortation for you to dream up a totally new and creative approach to a problem—a quite reasonable concept. However, it has evolved into such a cliché that it has lost all meaning. Today, it is a fallback phrase that merely means thinking beyond the tried and true. In my experience, if a manager keeps asking his colleagues to “think outside the box,” you can be quite sure that he or she is thinking firmly inside the box.

Similarly, don’t get bogged down by using obscure acronyms. There are some common acronyms such as ASAP (as soon as possible) and NYSE (New York Stock Exchange) that are generally understood. And every organization has its well-known shorthands for departments and procedures. It’s perfectly okay to use the acronyms that everyone knows by heart. But when the penchant for acronyms goes too far, it effectively excludes newcomers from the conversation.

I recently attended a meeting in Washington, D.C., where several people referred to the EGTRRA. Later I found out that “EGTRRA” stood for the Economic Growth and Tax Relief and Reconciliation Act of 2001, better known as one of the “Bush tax cuts.” I later went to an initial meeting at a company where the conversation revolved around OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) for ICDs (implantable cardioverter-defibrillators). Since those acronyms were not intuitively obvious to me, I had a hard time following the discussion. To help newcomers get up to speed, every organization should compile a list of acronyms that are peculiar to that industry or company and make that list freely available.

Getting Buy-In from Everyone

A meeting needs a proper ending: an agreement on actions to be done by certain people at certain times. That follow-up should be recorded in a list and distributed to all participants. But the list will be effective only if it reflects the collective consensus of the meeting, rather than the “word from on high” handed down by the boss.

At the end of a meeting, I always ask, “What are the action items, who’s going to do them, and when will they be delivered?” I want the participants to agree on the action items and set their own timetable for the deliverables. At most, I gently suggest that their timetables include a margin of error to allow for the possibility of unforeseen delays or problems.

By letting the participants create their own follow-ups and time schedule, I’m trying to create a sense of ownership in them. This principle is known as the “IKEA Effect,” named for the home furnishings retailer whose products are notoriously difficult to assemble. The IKEA Effect states that by forcing consumers to play an active role in the assembly of their dresser or bookshelf, they will value the product more highly than if it were assembled in store.11 In a similar fashion, by creating their own deadlines, employees will be more motivated to meet them. Indeed, I find that meeting participants often set more aggressive deadlines for meeting follow-ups than I would have requested.

1. Think hard about whether you really need to call a meeting. You can share information just as effectively via email or a phone call.

2. Politely decline meetings that will not advance your priorities or seem as though they will be unproductive.

3. Try to limit your attendance at your boss’s unproductive meetings by diplomatically explaining your workload.

4. Keep meetings as short as possible—schedule no more than ninety minutes at the maximum.

5. Hand out materials to be read one day before the meeting so that people have a chance to actually read the material.

6. Limit your opening remarks at meetings to fifteen to twenty minutes. Do not bore your audience to death with too many PowerPoint slides.

7. After the introduction, organize vigorous debate on the key points. The most powerful executive in the room must be willing to be challenged.

8. Keep jargon to a minimum at meetings—don’t use the word “synergy”!

9. Develop a list of commonly used acronyms so that newcomers can easily participate in the discussion.

10. At the end of the meeting, ask participants to collectively decide who should do each task and when each task should be completed.