CHAPTER 5

Aiken Day School

My mother and two of her friends, Mrs. Katherine Von Stade and Mrs. Elsie Mead, founded the Aiken Day School in my great-grandfather’s former squash court for their three oldest daughters, Pam, Dolly, and Katherine. My mother, who’d gone to Brearley, as had her mother, had persuaded the New York school to help them in setting up the school, and the curriculum was demanding. I realized how well I’d been prepared when, in ninth grade, I myself entered Brearley. The support and learning that took place within those Aiken walls formed my lifelong love for knowledge of all kinds.

Having left Barnard College to marry after only one semester, for many years I imagined that a college education would open windows to marvelous worlds of ideas, skills, and people. In my forties, with all our children in school, I enrolled in Manhattanville College. After seven years, I earned a BA, and was delighted by the publication of B. H. Friedman’s biography of my grandmother, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, for which I’d done research as part of my college credits. In that same year of 1978, I became president of the Whitney Museum’s board of trustees, embarking at fifty on a new life.

As I reflect now on the 1970s and ’80s, I see that Aiken and my consciousness of our family’s position there was a primary source of the inspiration, desires, and ambition that I developed in my middle years. As a child, growing up in a distinguished family, in the biggest house in Aiken, seemed natural. I didn’t acknowledge the obligations attached to my advantage, but when I married and had children, I disregarded my connection to my renowned ancestors, wanting for my own family a simpler life.

Later still, I realized that some of the people with whom I was working at the Whitney Museum had higher expectations of me than I had for myself. When I took on my new job, I accepted responsibilities that pulled me away from my home in Connecticut. Mike’s and my interests had diverged. Once a wife and mother, I became a working woman, plunging into the captivating and competitive cultural world of New York City. In order to lead the Whitney to fulfill its role as the primary museum of American art, as envisioned by my grandmother, I at last accepted my heritage, using my background to meet the powerful and wealthy people who could help. This seemed productive and good.

Lev’s and my wing of the house had its own entrance, with a little porch from which steps descended to the back driveway. A clay tennis court was to the left, and beyond that a greenhouse by an enormous pecan tree with gray Spanish moss dripping from its branches like the beards of Chinese sages. Between the ages of four and thirteen, from mid-Sepember to mid-May, I walked down the painted blue-gray steps, turned right, my polished brown brogues rattling the small pale pebbles, and followed a short path past lawns shaded by green-black pines to a weathered gray wooden gate. Skipping across the red clay of Easy Street, I reached my school. With its wide porches and big windows, the cottage-style building, set in a grassy plot, was solid and inviting.

Joye Cottage: my bedroom

The children’s entrance

The stables

Aiken Day School, now a house, c 1970

In a large square room with windows on two sides, ten to twenty boys and girls of different ages sat at wooden desks; their number changed from month to month and from year to year according to the length of time their northern parents had chosen to stay in Aiken. A few families, like ours, were the exception; the solid core. A big blackboard was at one end of the room, behind a desk for the teacher. In the one other room on that floor, we made maps, charts, wooden and clay artifacts, and sat on the floor to paint on big sheets of shelf paper. A central staircase led to the tiny room where we studied French.

Our teachers were an important part of our lives. First, always, there was Miss Lowe. Tall, beautiful, willowy, her long braided red-gold hair coiled around her head like a crown. Her translucent skin smelled faintly of almonds; her fingernails were perfect rose-petal pink ovals. Her smile, her gentle touch, conveyed the love she gave, I was sure, to me alone. It was due to Miss Lowe’s encouragement that I learned to read at four. Whatever she taught entered my head by magical osmosis. When nice Miss Prentice tried to teach me arithmetic, the magic wasn’t there, and the numbers did not instantly fall into the right place as the letters had done. Finally, when someone took me for eye tests, they found I was nearsighted, which explained why I couldn’t see the blackboard. Even with glasses, I never really conquered my difficulty with numbers.

Schoolroom, Aiken Day School. Lev Miller, me, ?, Marianna Mead, c. 1938

Workroom, Aiken Day School

After I outgrew Miss Lowe’s classes, I visited her often. She always made me feel exceptional. That I could accomplish whatever I wanted if I did my best. How fortunate are children who receive that gift. Smoothly and capably, they emerge from childhood well rooted, and able to deal with life. I was lucky to find such kindness and wisdom in my teachers, because as much as we loved one another, my parents were often absent in body and spirit. With both the means and the imagination to enjoy their seemingly superficial lives in the ways they chose, they were busy shooting doves, quail, ducks; riding or driving on the soft clay roads; playing canasta (Mummy) and bridge (Daddy); watching or participating in lawn tennis, court tennis, horse shows, polo games, horse races, hunts; giving or attending lunches, teas, dinners; offering drinks to the many friends who dropped in before meals; reading and traveling.

The one thing that was not done was to talk about money. Earning one’s living was rarely discussed. In Old Money, Nelson Aldrich illustrates the attitude of my parents’ caste in this anecdote about Herbert Pell, a leading New Deal Democrat from an old and rich New England family:

Schuyler Parsons, Elsie Mead, Yale Dolan

Herbert Pell’s views of the hard hustle and hump of middle-class life may be judged from a story still told about him: that when a favorite niece of his one day joyfully announced that her new husband had at last found a job, Uncle Bertie replied, ‘Oh, my dear, I’m so sorry.’ The great gift of inherited wealth, in Pell’s view, was freedom, and freedom ought to be put to better use—public service, for example—than holding down a ‘job.’

Very few of my parents’ friends actually worked; at least not when they were in Aiken. There were exceptions, of course. Schuyler Parsons ran a chic, popular shop for knick-knacks, wedding gifts, and furnishings. He was a popular bachelor, a natty figure with a Van Dyke beard and a sharp wit. Schuyler’s sister Betty, originally an artist, opened a gallery in New York City remarkable for the early recognition of Jackson Pollock, Louise Nevelson, Richard Tuttle, Agnes Martin, and many others. Later, she became my friend. I learned much from Betty, whose strength belied her tiny, waif-like appearance. I admired her generous, wholehearted approach to her artists and their art, hardly aware that she herself was a talented artist. My mother’s close friend Chi Bohlen, whose brother Chip later became United States Ambassador to France and Russia, worked hard, too—she was the manager of Schuyler Parsons’ elegant shop, and during World War II served in the Office of Secret Services, the precursor of today’s CIA. The OSS was more of a club then, with a certain cachet, where spying, dangerous as it was, was also glamorous.

The rather unnatural formality between myself and my parents made me care all the more passionately for my teachers and friends. Marianna Mead, a small rosy-cheeked girl, is still vivid in my mind’s eye. Everything about her is smooth, silky, and tawny: the chestnut ringlets framing her round, freckled face; her caramel pony, Queenie; her cocker spaniel, Taffy; her brown jodhpurs, honey yellow sweater, and tan hair ribbon. She had gold-flecked eyes, a merry smile and bouncy gait—it was no wonder her boarding school nickname was Muffin.

She was my best friend throughout our childhood; really my only friend. When school let out in mid-May, I endured the loneliness of our four-month separation while I imagined her with cousins and friends enjoying a lively summer on Cape Cod. She was the youngest of six children in a gregarious, successful family from Dayton, Ohio. The Mead Paper Company, owned by her father, George, provided material security, while her mother nurtured and organized the children, who grew up to become successful adults in their various pursuits. Marianna and her husband became teachers and school administrators, and after retiring they founded a flourishing business advising parents on school and college choices. Even as a child, I recognized the difference between Elsie Mead and my own mother. Occasionally, Mrs. Mead’s drive to galvanize us into activity intimidated me, and I retreated into the comfortable lassitude—reading for hours, taking long baths—that was acceptable at home, but not at the Meads’ house. Their pulsing energy also attracted me, and I wished my parents were like Mr. and Mrs. Mead, rushing about with their children like a flock of chickadees, inviting friends for meals and weekends, playing tennis, riding, even eating dinner together. It created a dichotomy that has been with me ever since those days: a desire for activity, for a social life, and a countering need for solitude and reflection. There was no ambiguity, however, in my wish that my strict English nanny be more like Marianna’s nurse, Alice; vivacious young Alice, endlessly kind, who played with Marianna. She even laughed. I’d grown to hate the plain dresses the local dressmaker produced every fall for my plump self, envying my friend’s store-bought dresses in pretty prints with waists and swinging skirts. Marianna’s world was much more eventful than mine, and far more fun. Even Marianna’s school lunch was more exciting than mine, which always contained the same ham and cheese sandwich and dried figs, while hers was likely to have fried chicken, corn cakes, and delicious cookies and brownies. Although I was a year older than she and a grade ahead, we shared classrooms and teachers in our small schoolhouse.

Marianna Mead on Queenie, with her sister and pets, c. 1937

One of the other students, Philip von Stade, was one of eight children. Marianna and I were equally smitten by Philip’s blond curls, his teasing, his dimples. We chased him at recess, tagging him “it” over and over, not yet aware of our subconscious wish to touch him. Our schoolmates Seymour and Norty Knox, wiry and quick, were destined for great athletic success, becoming high-goal polo players whose teams consistently won international competitions. My brother, Lev, and his friends Jimmy and Timmy Laughlin, were too young to be of interest, but old enough to be nuisances. I doubt we were sorry when they transferred to the new boys’ school, Aiken Prep. It meant more attention for us from our beloved teachers.

Kitty and Nanny von Stade were the sisters of our hero Philip and of my older sister Pam’s best friend Dolly, but so much younger than Marianna and me that they didn’t really count. Claudia Wilds, the doctor’s daughter, was the only real Southerner in the little school; she spoke with more of an accent than our teachers. Her parents had less money than ours, and even her clothes were different—cut so they’d last. We couldn’t understand why she didn’t have her own horse, like the rest of us. Why she wasn’t a good rider. In the photograph I still have of Marianna, Claudia, and myself carving a Halloween pumpkin, Claudia looks sad and lost. And doubtless she was. As children can be, before learning the more subtle ways of adults, we were sometimes cruel. Prejudiced, before even knowing the word.

With Claudia Wilds, carving a pumpkin

Eithne Tabor, a tiny fiery redhead, was the daughter of the headmaster of the boys’ school. Thinking her a crybaby in the games we played at recess, we tried to exclude her, which, of course, only made things worse. “What have you been doing to poor Eithne to make her so unhappy?” our parents asked. “You should make a special effort to include her. She’s new, you know, and she’s younger than you are.” So we knew that Mr. and Mrs. Tabor complained to them, and we resented Eithne all the more.

Marianna, above all, was my constant companion. Unlike my children and grandchildren, we didn’t have play dates or sleepovers. In our small community, we necessarily followed the same routine. Marianna and I shared secrets, played games, teased Lev and his friends. We had our dogs: her golden cocker spaniel, Taffy, and my long-haired dachshund, Gili-Gili. We took tennis lessons, and we even performed tap-dances with local girls in the local school gymnasium. (We weren’t real Southerners, like our dancing partners, as a group of them made very clear one day, shouting at us from the steps of the post office, “Go home, damn Yankees!” Once out of their sight, I shed tears of shame, sorrow, and incomprehension.) We took piano lessons. We hated to practice, playing duets like “Sur La Glace A Sweetbriar” under the baleful eye of Miss Stoddard, whose one long hair, growing from a mole on her cheek, both fascinated and repelled us.

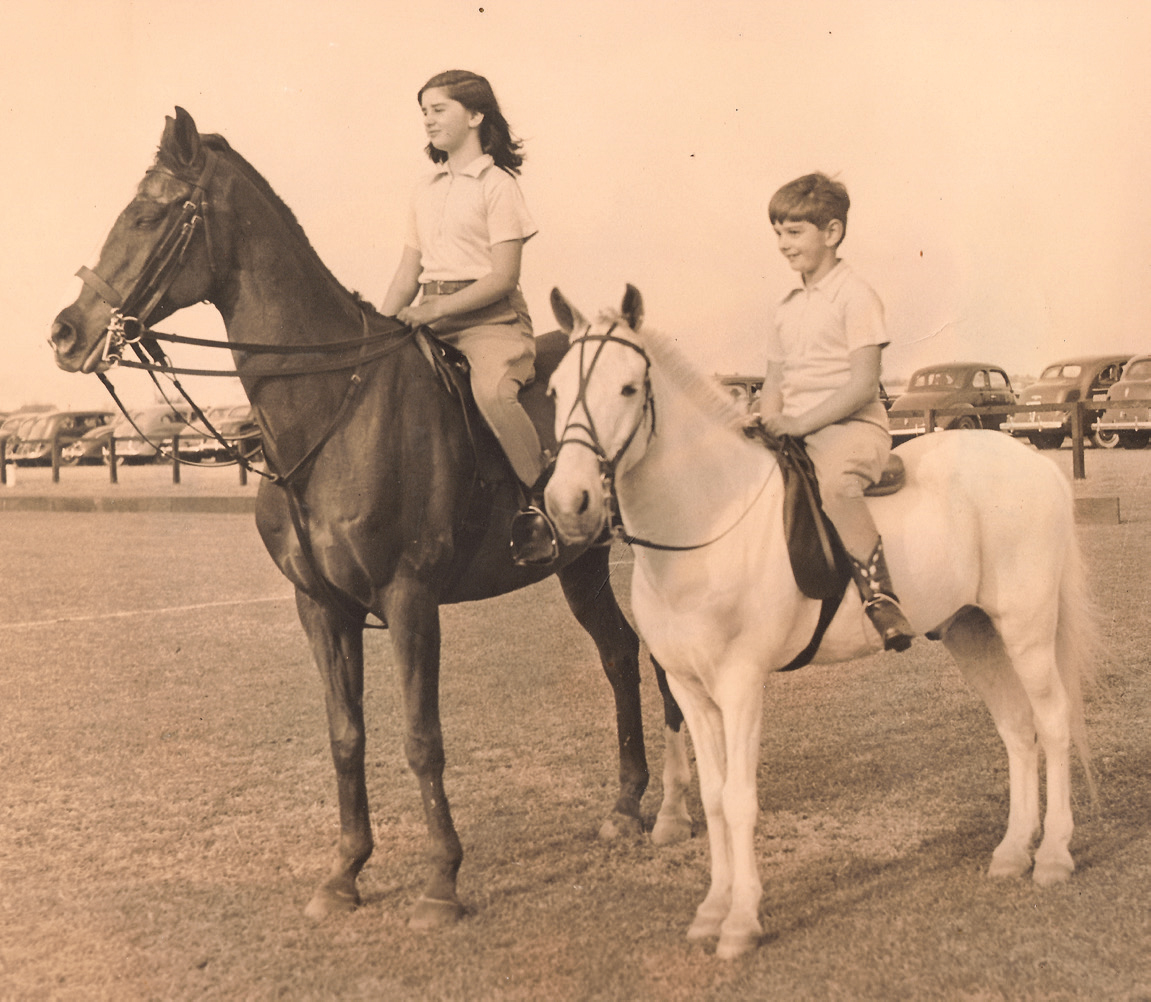

Above all, though, there was riding. We rode every day but Sunday; two or three times a week with our teacher, the other days with the grooms. Snowball, white, calm and gentle, was my first pony, followed by others more suitable for the jumping to which we all looked forward. Queenie was Marianna’s pony, a furry butterscotch with a vanilla mane and tail. On this small beauty, she galloped over soft piney trails and vaulted over big jumps.

“Legs, body, reins—Whoa!” called our teacher Gaylard in a deep, commanding voice. Squeeze the thighs. Lean the body back. Only then, a slight pressure on the bit. These were religious precepts. Leaning back, down we’d go—my pony seemed to slide on his tail as I squeezed my knees against the saddle, hoping not to plunge over his head to be trampled. Up the bank—hup! I leaned forward, sure I wouldn’t be able to grip hard enough, sure I would slide right down his tail.

Horseshow, Aiken: With Lev on Snowball and my father, c. 1937

Going home, we crossed Sand River. An old legend told of an Indian chief of the Creek Nation whose daughter had been very ill. Guided by a dream, he had her carried to a land of whispering pines through which flowed a river of sand. Here, the Indians built a village, and in the healthy climate of Aiken the princess recovered. In that same river, Snowball kicked up the fine white sand, tickling his belly. When he bucked, I was thrown into the surprisingly unyielding, cold drybed. “Whoa there!” I heard my teacher call as he chased my excited pony, catching him, and bringing him back to me, salted white, dazed. “Now, Flora, what have I told you a dozen times?”

“Hold onto the reins when I fall off, Gaylard.”

“That’s right, Flora. The next time, you’ll walk home, leading your horse. Now mount him and let’s go.”

He ignored my hot tears of shame. I mounted my pony and followed at the end of the line of riding pupils. The next time, two or three weeks later, I did walk the long trail home, leading Snowball. And the time after that, I held onto the reins.

Captain William Gaylard was in many ways the most important adult in our lives. He was not a tall man, but to us, his pupils, he was a warrior of Herculean proportions. We knew that he’d been a British cavalry officer in the Boer War. His erect posture, neatly clipped moustache, immaculate jodhpurs and tweed jacket, polished boots, silver spurs and checked cap identified him from afar, even to my nearsighted eyes. I didn’t wear my glasses when riding, afraid of breaking them when, as often happened, I fell from my pony.

Throughout those childhood years, our physical and emotional worlds revolved around horses. My budding sense of myself waxed and waned through my proficiency—or lack of it—in controlling a powerful quadruped whom I both loved and feared. My character was shaped by this, filtered through the discipline of our mentor and coach. The idea of control was the key to maturity. I recognize it as a motif running through my life. It is still with me today—the conviction, as I was taught, that I can dominate events or people. Thinking it possible, when it so clearly isn’t. Believing that if a thing is right, it will happen.

On Jackie, Lev on Snowball, c. 1937

On Redbank, Lev on Snowball, c. 1938

Much later, as president and then chair of the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art, I discovered the fallacy of my illusion. As we were raising money for a major building expansion, many trustees were losing confidence in the director with whom I’d been working closely. I continued to support this director, although the most powerful men on the board, those with the money to enable the expansion, wanted him out. In the end, the board voted to fire him. I was devastated. With a split board, the expansion was cancelled. Many artists shunned the Museum that had long been their home. After much negative publicity, attendance decreased; and the director’s career was irretrievably damaged. If I’d been wiser, some of these effects would have been lessened. By admitting that I couldn’t have my way, a compromise might have been possible. Instead, I stuck to my position, and lost. I foolishly took for granted my fantasy of entitlement, and I hurt the institution I loved.