Chapter 8

Jinx and Henrietta, the other two members of the committee, came out from behind a bush where they had been hiding and ran over to Freddy.

“Freddy!” said Henrietta. “Isn’t this awful! What’ll we do?”

“Boy, oh boy!” said Jinx in an awed voice. “I know what I’m going to do. I’m going back to the house and pack up my rubber mouse and my catnip ball and beat it. I wonder if the sheriff needs a good cat down at the Centerboro jail?”

“You can’t do that,” said Freddy. “We’ve got to help him out, anyway. Maybe he’s hurt.”

“He isn’t yelling any,” said Jinx.

“Mr. Bean wouldn’t yell, even if he was hurt,” said Henrietta. “But he can’t be. That’s why we put the mattress there—so Jimmy wouldn’t hurt himself.”

“Well, come on,” said Freddy. “We’ve got to see. But what can we tell him?”

“Tell him the truth,” said Henrietta sharply, “and take our lickings.”

“Mr. Bean never licks us,” said Jinx.

“No, but it’s the way he looks at us when we’ve done something,” Freddy said. “I’d rather have the licking any day.”

“Ho, hum,” said Jinx. “No cream for a month, I suppose. Well, let’s get it over with.” Like most cats, Jinx never worried much about hard looks as long as they weren’t accompanied with broomsticks or going to bed without supper.

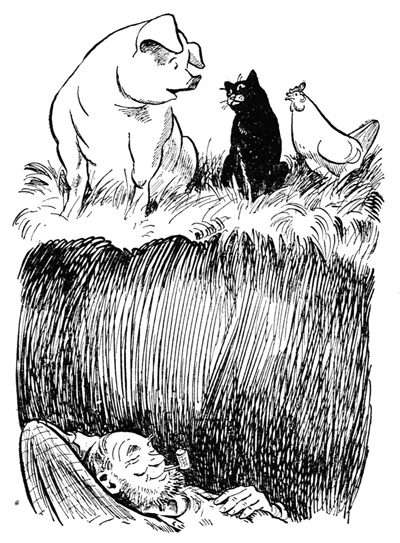

They went up unhappily to the edge of the pit and looked down. Mr. Bean was sitting comfortably on the mattress, puffing his pipe, which apparently he had kept in his mouth all the time. When their shadows fell across him he looked up, but he didn’t say anything.

Usually Mr. Bean didn’t like to hear animals talk. He said it wasn’t fitting. I suppose he meant by that that it is a little unusual to hear an animal talk, and he didn’t like unusual things much. I suppose that was why he had worn the same hat for thirty years.

“Well—Mr. Bean,” Freddy stammered, “are you—are you all right?”

Mr. Bean grunted. Then he said: “If I had a mug of cider I’d be as happy as a moth in a blanket.”

“I—I guess we don’t understand, sir,” Freddy said. “We saw you fall in, and—well, we came to help you out.”

“Preserve us and keep us!” said Mr. Bean, and a puff of smoke came out with every p. “What for? This is the first time since I started farming it, fifty years ago, that I’ve been in a place where I can look around me and not see a lot of work that has to be done. The first time I’ve been in a place I couldn’t get out of to go look for more work.” He puffed thoughtfully for a minute. “Only thing is,” he said, “I don’t know how I got here. I was chasin’ that consarned Witherspoon boy, and then I was sitting here, smoking my pipe. There must have been something between.”

“We know what it was,” said Freddy. “We’re responsible for it.”

“I give you my thanks,” said Mr. Bean.

The committee looked at one another. Mr. Bean wasn’t taking it the way they had expected him to. But maybe when they told him—

The committee looked at one another.

He looked at them shrewdly. “Better not say anything more,” he said. “If you tell me, I’ll have to do something about it, and I don’t feel like it right now. Go away, go away!” he said irritably as Freddy started to speak. “Sometimes you animals don’t know when you’re well off. But wait!” he called as they drew back. “Better send Hank up here after a spell to pull me out. I expect Mrs. B.’ll worry if I’m not home to dinner.”

The animals started back slowly towards the farmyard. “Well, I guess it’s all right,” Freddy said. “But I can’t figure out why he isn’t good and mad.”

“Maybe he fell on his head,” said Jinx. “My grandmother fell off the roof once and landed on her head, and she always acted queer afterwards. She used to have fits.”

“Don’t talk nonsense!” said Henrietta sharply. “Mr. Bean isn’t having fits. He’s enjoying himself. Goodness to gracious, I’d like to get into a nice quiet place like that myself! It would certainly be a change from that henhouse, with thirty cackling children tearing around and asking questions and always wanting something, and Charles practicing his speeches. Well, we’ve tried my plan, Freddy, and we’ve tried yours. Now let’s try Jinx’s.”

So they went back and gave Hank Mr. Bean’s message, and then they went down to Freddy’s study in the pig pen and made out a list of all the animals and birds that would be useful in carrying out Jinx’s plan. This plan was very simple. It was based on the fact that if a person is kept awake all night, he isn’t likely to be very lively the next day. If they could wake Jimmy up every half hour all night long, he wouldn’t feel much like running around and throwing stones at animals in the morning; he would probably spend most of the day sleeping. And if they did it several nights running, he would probably be willing to let them alone if they would stop bothering him. Jimmy went to bed at nine, and got up with his parents at five. That meant that he would have to be waked up fifteen times during the night.

“It means a lot of night work for all of us for a while,” Jinx said, “but if we divide it up it won’t be so bad.”

So Freddy made out a schedule on his typewriter.

9:30. Jinx yells

10:00. Freddy squeals

10:30. Charles crows

11:00. Henrietta cackles

11:30. Robert howls

12:00. Georgie yelps

12:30. Emma quacks

1:00. Hank neighs

“I don’t know about Hank,” Freddy said. “He’s so big, he couldn’t get out of sight quick enough if Jimmy was laying for him. And we’ve got to remember that he will lay for us after the first few times.”

“If Hank keeps to one side of the window he’ll be all right,” said Jinx. “Jimmy’d have to light a lantern before he could look round. Old Witherspoon doesn’t own a flashlight; he always uses lanterns.”

“But Hank’s white,” said Henrietta, “and the cows are too. I think we’d better leave them out of it.”

“Well, it’s only one o’clock, and we’re running short of animals,” Freddy said. “Some of us will have to make two trips.”

“How about Old Whibley?” said Henrietta. “He’s up most of the night anyway.” Old Whibley was the owl, who lived up in the woods with his niece, Vera. “A couple of those hoots of his will scare Jimmy right out of his nightshirt.”

“And Vera’s got a screech that will scare him right out of his skin, after his nightshirt is gone,” said Jinx. “Boy, you won’t have to put anybody on for an hour after Vera cuts loose.”

“I think they’ll do it,” Freddy said. “He’ll grump and grouch about it a lot, but he’ll do it.” And he wrote down:

1:00. Whibley hoots

1:30. Vera screeches

2:00. ?

“We’re still about five animals short,” he said. “I suppose each of us could stay and wake him up twice.”

Jinx said no, that wouldn’t do. It ought to be a different noise each time. “If it’s the same sound, he’ll know what to expect and get used to it. It’ll scare him more if he doesn’t know what to expect.”

“I wish I knew a wildcat,” said Henrietta. “That is, I wish I knew of one. I wouldn’t care to meet one personally.”

“Let’s look over the different noises,” said Freddy. “I mean, what noises haven’t we got down? Let’s see—we haven’t got twitter or chirp or buzz or growl, but they’re not scary noises. I can grunt, but a grunt is a sort of soothing sound—”

“Says you!” Jinx exclaimed. “How about ‘snort’ and ‘bellow’? And ‘bawl’? Who can we get to bawl?”

“I wish Mr. Boomschmidt’s circus was around,” Freddy said. “We could get Leo to roar. Golly, if that lion roared in Jimmy’s window—!”

“If, if, if!” said Henrietta impatiently. “We can’t work with if’s. We’ve got to use what we’ve got. Freddy, how about your going up and getting Uncle Solomon to help us out?”

“Great!” said Jinx. “That would give us ‘shriek’ and ‘scream’ all rolled into one nice horrible package. Yes, you go see him, Freddy.”

Freddy didn’t want to go. Uncle Solomon was a distant relative of Old Whibley’s, a small screech owl who lived all alone in the Big Woods. Like all owls, he was a terrible arguer. Freddy didn’t mind that so much, but nobody had ever been able to win an argument with Uncle Solomon. He could take either side of an argument—and indeed he would usually offer to change sides right in the middle of one; but whichever side he took, he always won.

Now with some arguers, if you want to persuade them to do anything, you have to start by trying to persuade them not to do it. And they will argue themselves right into doing it. But with Uncle Solomon you couldn’t ever tell where to start. But at last Freddy agreed to go see him.

So he went up into the Big Woods and rapped on the trunk of the tree in which the owl lived. “Uncle Solomon!” he called. “Can I see you a minute?”

The little owl flew down at once and perched just over Freddy’s head. And he said in his small precise voice: “That depends, does it not, on just what you mean by the word ‘see’? Do you mean that you wish to consult me upon some matter, or that you merely wish to look at me? I assume that it is the latter, since the ‘minute’ which you mention contains only sixty seconds, and is therefore hardly long enough for a consultation of any importance. Indeed it is now up, and as you have done what you wished to do—namely, seen me for a minute, I will say good morning.”

“Oh, dear!” said Freddy hopelessly, and then he got mad. “Oh, all right,” he said. “If you want to be that way about it, I’ll go home. Just forget the whole thing.” And he turned and started back.

But Uncle Solomon loved to argue—which I suppose was only natural, as he always won. And in addition, he was a lot more curious than owls usually are. Old Whibley would have said: “Good!” and flown back into his nest and gone to sleep, but Uncle Solomon gave his long tittering laugh. “Dear me, how very touchy you are, young pig! Come, come; present your case.”

So Freddy came back and told him about Jimmy and their plan for keeping him awake. He talked fast so that the owl wouldn’t be able to stop him, but Uncle Solomon was always very mannerly. He never interrupted. But when you were all through, he would begin and take your whole argument to pieces.

When Freddy had finished, he said: “I do not like boys who throw stones, and I am therefore inclined to assist you. But there are one or two points in your statement which do not appear to be logical—”

“Oh, please!” said Freddy. “If you’ll just come down! And anyway,” he said, thinking that he could perhaps turn the owl’s own method of argument against him, “how can you say that there are one or two? If there is one, there can’t be two, and if there are two, then you shouldn’t say ‘one or two’—isn’t that so?”

“Very well reasoned,” said Uncle Solomon. “But I was using the phrase ‘one or two’ in the accepted sense of ‘several.’ There are, in fact, six. And to begin with the first one:—”

“Excuse me,” Freddy cut in; “I really have to get back. I don’t want to interrupt you—”

“You do want to, or you wouldn’t,” said the owl. “And conversely, if you didn’t want to, you would. Which proves, of course, that you really don’t know your own mind.” He laughed his neat little laugh. “Correct me if I am wrong.”

“Oh, I don’t care whether you’re right or wrong,” said Freddy, “if you’ll only show up down at the Witherspoons’ at half-past two tomorrow morning, and scream in Jimmy’s window. We’re counting on you. But goodbye for now.” And he ran off. But before he was out of earshot he heard Uncle Solomon starting to tear his remarks to pieces. “Show up down at the Witherspoons’! Well, is it to be up or down—you can’t have it both ways …”

It took the rest of the morning to get all the animals lined up and persuade them to do their part, but most of them were willing, and they all felt pretty sure that after a night or two of being kept awake, Jimmy would give in. Freddy and Jinx were going to stay up all night, because not only would they have to make two visits each to the Witherspoon house, but they would have to be sure that none of the others overslept their appointed times. And Freddy was just going down to his study to take a nap until supper time when he met Mr. Bean.

“Ah!” said Mr. Bean, and stopped.

Freddy stopped too, but he didn’t say anything. For perhaps a minute they looked at each other, then Mr. Bean leaned down and slapped Freddy on the shoulder. “Smart pig,” he said. “Know enough not to make explanations.” He straightened up and looked off thoughtfully over the fields, puffing his pipe. “Got a lot of thinking done this morning,” he said, as if talking to himself. “Good place to think, down that hole. Guess we’d better keep it. Anybody wants to think, leaves word when he wants to be pulled out, then jumps in and thinks.” He bent and slapped Freddy again. “If you need any help with that Witherspoon boy, let me know,” he said, and went on towards the house.