Chapter 10

On the day that J. J. Pomeroy was to get his glasses, he and Mrs. Pomeroy flew down to Centerboro together. J. J. had learned to manage his new tail by this time; he no longer bumped into trees or turned unexpected somersaults in the air when he changed direction in flight. He was very pleased with the long white plumes that streamed behind him, although some of his neighbors were rather sarcastic about it. One of them, a wren who lived in the same tree, had remarked that the first time she saw J. J. fly past she thought he was coming unraveled. Mrs. Pomeroy no longer spoke to her.

Mr. Watt didn’t recognize J. J. at first. When the two birds flew in his window he tried to shoo them out, but they managed to explain and then he brought out the little spectacles he had made. He had done a beautiful job. The lenses were only about half the size of your little fingernail, and they were set in small gold frames, and the side pieces hooked together at the back of J. J.’s head. Mr. Watt put them on and adjusted them, and then he held up a mirror so J. J. could see how nice they looked.

“Good gracious!” J. J. said. “I’m quite handsome!”

“You always were, dear,” said Mrs. Pomeroy loyally.

“That may be,” said J. J., “but you must remember that I have never had a good look at myself before. I’ve tried to see myself in windowpanes, but they’re never very good, and then I was so nearsighted that I always had to get so close that my beak was against the glass. And all I could see was my eyes.”

“Such nice eyes!” murmured Mrs. Pomeroy.

“They’re the most beautifully made pair of glasses I’ve ever seen,” said Mr. Watt, who was never one to underestimate his own work.

“They’re very nice indeed,” said Mrs. Pomeroy. “But Mr. Pomeroy is a very handsome bird.”

“Sets off my glasses well,” Mr. Watt admitted.

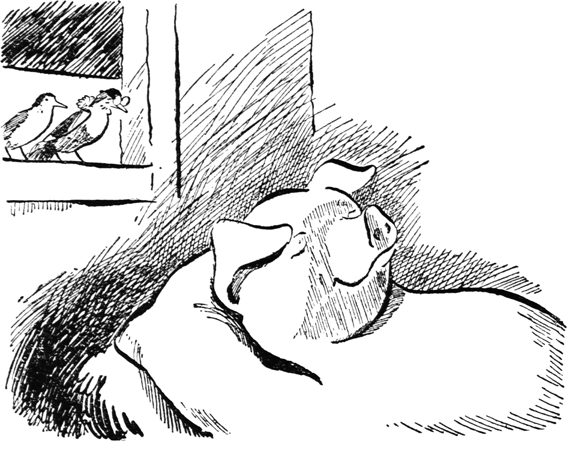

On the way back to their nest they stopped in to see Freddy and show him the glasses. Freddy was taking a nap. He had slept for two days after the animals had abandoned the yelling campaign against Jimmy, but by now he had made up all his lost sleep. This was just one of his regular naps. He always took several every day. He said it kept him on his toes. I guess Uncle Solomon would have given him a good argument about that statement.

The Pomeroys didn’t like to wake Freddy, so they flew on home. And by and by the pig woke up. He had been dreaming that the two boys, Adoniram and Byram, were still living on the farm, and that they had been kicking around the football that someone had given them, and that they had then gone up to the duck pond for a swim. “Guess I’ll go for a swim myself,” Freddy thought. He knew that the animals all expected him to go talk to Mr. Bean about Jimmy that afternoon, but he thought: “I’m all hot from sleeping so hard, and I don’t want to talk to Mr. Bean when I’m hot and sticky. I wonder why it is that it makes you just as hot to sleep hard as to work hard? I suppose it’s because even in my sleep my mind is so active.” He was pleased with this idea; it seemed to make all those naps pretty praiseworthy. He had always claimed that his best ideas came to him when he was asleep, and that his mind was at work all the time. If he perspired in his sleep, that proved it, didn’t it?

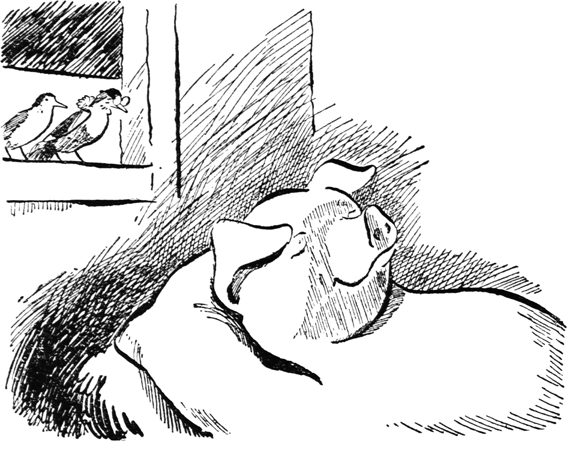

When he got to the pond, he found Alice and Emma sitting on the bank, watching Mrs. Wiggins, who was trying to learn to float. All he could see of the cow was four hoofs disappearing under the water; the rest of her had sunk.

“She always does that,” said Emma, who seemed not at all disturbed.

“But she’ll drown!” Freddy exclaimed. He ran out on the springboard which Mr. Bean had put up for the boys two summers ago and was about to dive to the rescue, when there was a great bubbling and commotion in the water, and first one horn appeared, and then the other, and then Mrs. Wiggins’s head broke the surface. It came up with a sort of bubbling roar, for Mrs. Wiggins had got to laughing under water. It isn’t a very good place to laugh. She had swallowed a lot of water and got a lot more up her nose, and she coughed and laughed and snorted and whooshed for several minutes. Freddy retreated from the springboard, and even the ducks backed away until she had got her breath again.

And then Mrs. Wiggins’s head broke the surface.

“You oughtn’t to go in swimming when you’re alone,” Freddy said. “You might have drowned.”

“I suppose I might have, at that,” said the cow. “But it’s such fun when I think I’m going to float, and then I just sink. Each time, I think: ‘Now this time, Wiggins, you’ll stay up.’ It seems so easy. And then down I go!” And she began to laugh again.

“She’s been doing it all morning,” said Emma, and Uncle Wesley waddled out grumpily from behind a clump of goldenrod where he had taken shelter, and said peevishly: “I suppose she’ll drown eventually, but in the meantime nobody else can get anywhere near the pond. I wish she’d hurry up.”

“I must say, I don’t see what fun you get out of it,” Freddy said.

“I don’t either, Freddy, but I do,” said the cow. “It just tickles me when I think I’m floating around all cool and pretty like a lump of ice cream in an ice cream soda, and then plunk!—my back hits the bottom. It’s me, thinking I’m one thing, and really being something else; that’s what makes it funny. It would be just as funny to me if it was you.”

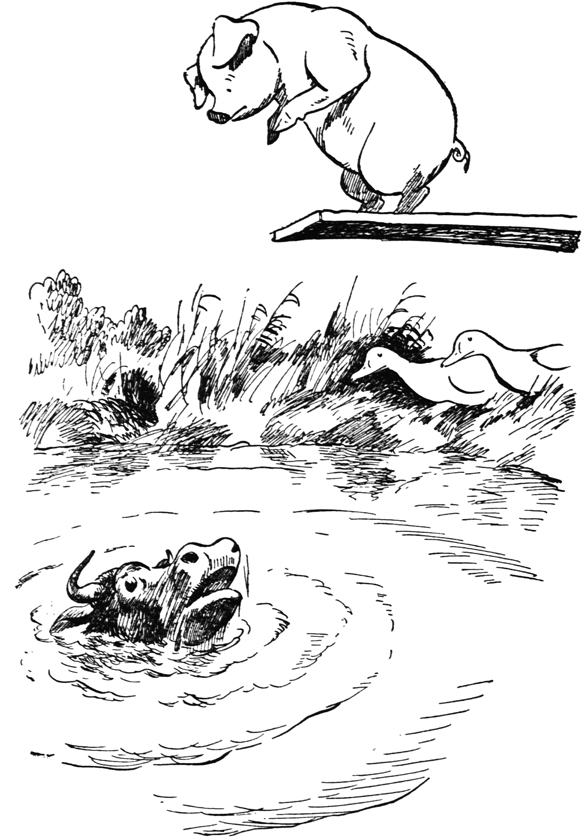

“Well, it wouldn’t be as funny to me,” Freddy said. And as Mrs. Wiggins got out on the bank, he walked out on the springboard, bounced twice, and soared up and then down in a long clean dive.

“Swan dive,” said Emma. “Very pretty, I always think.”

“Land sakes!” said Mrs. Wiggins. “There’s nothing much to that! I’ll wager I can do as good.” And before anybody could stop her, she was out at the end of the springboard. “Three jumps, and then up I go. One … two …”

Crash! The board, struck for the third time by several hundred pounds of cow, broke short off, and with a tremendous splash Mrs. Wiggins went down into the pond.

“Oh, my goodness!” said Uncle Wesley disgustedly, and waddled hurriedly back to the clump of goldenrod.

Presently Mrs. Wiggins’s head reappeared. “How’s that, Freddy?” she spluttered. “You and your swan dives! I bet you couldn’t do one like that. I bet no swan could dive hind end first, either.”

“Well, I’m glad you broke the board,” said Freddy. “This pond isn’t big enough for any animal your size to practice diving in.”

“Ought to hire herself an ocean!” came a grumble from behind the goldenrod.

“You remember, Freddy,” said Mrs. Wiggins, climbing out and shaking herself, “the games we used to play in the pond when the two boys were here? Remember the water polo games?”

Freddy remembered them very well. Byram and Adoniram had wanted to play all the games that other boys play, particularly such games as are played between opposing teams. But in the summer there weren’t enough other boys in the neighborhood to make up two teams, so they had to fall back on the animals. They had chosen up sides and tried to play baseball first. But although most of the animals could catch a ball, either with a glove or in their teeth, none of them could throw, and the only animal who could bat was Peter, the bear, and he was so strong that when he really connected with the ball he usually knocked the cover off, and then the game stopped until somebody went to Centerboro and bought a new one.

Football and basketball hadn’t worked out well either, for about the same reasons. But water polo had been a success from the start. All the animals could swim, and they could all knock a ball in the direction they wanted it to go, with hoofs or paws or heads. At first some of the smaller ones had been at a disadvantage, until a rule had been made that cows and horses could only use their heads, and not their hoofs, in hitting the ball. After that the two permanent teams—Byram’s Red Pirates and Adoniram’s Rural Commandos—had played a long series of games. Mr. Bean had even come up and umpired some of them.

“Yes, sir, those were great games,” said Freddy. “I saw that ball we used to play with just the other day, when we were up in the loft. Made me quite homesick for the old days. I started to write a poem about them. It went like this:

When I was a piglet, the grass was much greener,

Always looked as if it had just come from the cleaner,

And life was much gayer, in so many ways.

Ah, those were the days!

Now I’m old, and my joints are increasingly creaky;

My hearing is poor, and my memory’s leaky;

And I weep as I put down these sad little rhymes.

Ah, those were the times!

In my youth, I was always prepared for a frolic;

I never had pains, rheumatism or colic;

I never had aches: head, stomach or tooth.

Ah, the days of my youth!

“Good land, Freddy, you sound as if you were about ninety years old,” Mrs. Wiggins said with a laugh.

“Well, I will be some day,” said Freddy, “and then this poem will be all ready for me. Ho, hum; yes. You know, just thinking about what it will be like when I’m as old as that makes me feel pretty feeble.” He rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “I could have sworn I had a long grey beard.”

“I don’t like sad poetry,” said Emma. “Dear me, there are enough cheerful things in the world without thinking up such mournful ones to write poems about.”

“I agree with you,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “I think Freddy probably needs a good dose of sulphur and molasses to tone him up a little.”

“No, thanks,” said Freddy. “But I wouldn’t mind limbering up my creaky old joints with a good game of water polo. What do you say, Mrs. W.? Shall we round up the others, and I’ll get the ball. Of course, we haven’t got the boys to captain the teams, but …” He stopped short and stared with narrowed eyes at the cow. “Golly!” he said. “Boys.” Then he whirled and dashed off at top speed towards the barnyard. “Stay right there till I get back,” he shouted over his shoulder.

Emma sighed. “I expect he’s coming down with another idea,” she said resignedly. She knew from experience that when Freddy got one of his ideas it usually meant a lot of work, and probably trouble, for everyone.

“I’ve said before and I’ll say it again,” said Mrs. Wiggins flatly, “that all these ideas aren’t healthy. Sulphur and molasses—that’s what he needs. There isn’t an idea that a good dose of sulphur and molasses won’t cure.” And she went on to tell of boys she had known of who, thoroughly dosed with sulphur and molasses every spring, had been completely free from ideas all the rest of their lives.

While they were discussing this, Freddy ran down and got his barrel-head shield, and then he went up along the fence looking for Jimmy. And pretty soon he found him. The boy jumped up from where he had been hiding and threw a stone. “Yah!” he shouted. “Thought you were pretty smart, keeping us awake all night, didn’t you?” And he threw another. But he didn’t seem to be mad, and that was a good sign.

Freddy caught both stones on his shield. “I guess we weren’t so smart,” he said. Then he backed away until he was out of range.

“Hey, come back!” said Jimmy. “Let’s see you catch some more stones.” It seemed evident that he thought of his stone-throwing—at least when he threw them at Freddy—as more of a game than a fight.

“Can’t,” said Freddy. “Have to go.”

“Oh, come on.” Jimmy came over and leaned on the fence. “There’s a tree up here—my father doesn’t know what it is. I want to ask you about it.”

This was so clear an invitation to a truce that Freddy almost weakened. But he knew he had a better plan. “Not now,” he said. “We’re playing off a big game this afternoon, up at the duck pond. Water polo. Championship match. Red Pirates vs. Rural Commandos.”

Jimmy said: “Oh,” and looked down at the ground. “Didn’t know you played games,” he said. He dug in the grass with a bare big toe.

Freddy thought: “I’ve got him hooked. Better not say any more.” So he just waved his shield. “Be seeing you,” he called, and trotted off. A minute later when he looked back, Jimmy was still leaning on the fence, looking down at the ground.

In half an hour Freddy had got the ball and rounded up the other animals, and after he had given instructions to the two rabbits whom he was employing as spies, he and Mrs. Wiggins chose up sides. Freddy had Hank, Mrs. Wogus, Robert and John, the fox who usually spent his summers on the farm; Mrs. Wiggins had Mrs. Wurzburger, Bill, the goat, Georgie, and Freddy’s cousin, Weedly. Although they hadn’t played in a long time, they were tough experienced teams, and when they had taken their places and Jinx, the umpire, tossed the ball into the water, the pond began to boil with activity.

In the first ten minute period, Freddy’s team scored two goals. But before the second period started, Mrs. Wiggins gave her team such a stirring pep talk that in the first half minute of play, they rushed their opponents not merely off their feet but practically under water, and tied the score. Then Freddy’s team pulled itself together and held the score even until Jinx called time.

They were resting after this period when one of Freddy’s spies came up and whispered in his ear. Freddy went over to Jinx and talked to him earnestly for a minute or two. Jinx looked surprised, but he nodded. Then Freddy went back and lay down to rest again. But when it was time to get up he just lay there and closed his eyes. And when they called him again, and he was sure everybody was looking at him, he squealed feebly several times and began to pant.

They crowded around him. “Freddy!” said Mrs. Wiggins. “What is it—what’s the matter? Are you sick?”

“No, no—it’s nothing,” Freddy gasped. “I’m just exhausted, that’s all. Can’t take it—way I used to. Ah, the days of my youth!” he quoted, and moaned a little.

The animals were alarmed—all but Jinx, who knew Freddy’s plan. Hank said: “You sure look terrible, Freddy. Don’t seem as if anybody could be as sick as you look. Though I dunno, maybe they could be sicker. But they’d have to try hard.”

Freddy struggled up on one elbow. “No, no; I’m not sick. Just tired. But carry on, my friends. I insist—the game must go on.”

“There’ll only be four on our side if we go on,” said Mrs. Wogus. “We’d better stop anyway—”

But Freddy insisted. He’d be all right as soon as he’d rested a little. “Jinx, you’ll have to find a substitute for me.”

So Jinx called in a loud voice: “Anybody want to play? Anybody want to take Freddy’s place in the game?”

“There’s no sense in that,” said Robert. “Everybody on the farm that can play is here now.” But Freddy waved his hand towards the woods that came close to the bank on the far side of the pond. “There’s somebody in among those trees; I just saw him move.”

The animals looked. They hadn’t noticed him before, but now they saw Jimmy, standing under the shadow of the trees. He had been there for some time, watching the game longingly.

The animals drew together at sight of the enemy, but Freddy said in a low voice: “It’s all right; I planned this.” Then Jinx called to the boy: “Hey, you! Want to play? Come on—you’re holding up the game.”

Jimmy came slowly forward. He would have refused a polite invitation to play. But if you take it for granted that someone will do something, nine times out of ten they will do it. Jinx had seen that, and his offhand manner had turned the trick. Jimmy didn’t say anything until he reached the edge of the pond. Then he said: “I’ll get wet.”

All he had on was a pair of patched overalls, which water certainly wouldn’t have damaged much. But Freddy—who was sitting up now, though he still didn’t seem to have the use of his legs—asked Georgie to run down to the house and ask Mrs. Bean for Adoniram’s bathing trunks. While they were waiting he explained the rules to the boy. And when the trunks were brought, Jimmy put them on and the game continued.

Freddy sat on the bank and watched. Jimmy didn’t know much about teamwork. He played as if he were all alone. He never passed the ball to others on his side, and never apparently expected them to pass it to him. But all the animals knew by now what Freddy’s idea had been, and they let Jimmy play in his own way. He could learn about teamwork later.

Of course as in all games there was a good deal of laughing and shouting and complaining, and there were several disputes which Jinx had to settle. Jimmy took no part in all this, but after a little he did begin to laugh. He laughed so hard when the animals splashed the umpire for making a sour decision that he swallowed a lot of water—which by now was pretty muddy—and had to be pulled out and whacked on the back until he stopped coughing. After that he seemed to begin to feel that he was one of the crowd.

After the game—which was won of course by Jimmy’s team—the boy dried himself with a bath towel which Mrs. Bean had thoughtfully sent up with the trunks, and got back into his overalls.

“Well,” he said, “I—I’ve got to go now.”

So the animals thanked him for playing and said goodbye. As he started off towards home, he stopped and turned uncertainly back.

“When,” he said, “—when do you—” And he stopped.

“When do we play again?” said Freddy. “Oh, tomorrow, I guess, if it’s sunny. We’ll let you know.”

“Well,” said Jinx when he had gone, “this is the second time we’ve got him into the pond. But this time I guess it’s going to take.”

“We hope,” Freddy said. “Anyway, I’m glad we didn’t have to ask Mr. Bean to help us.”