Chapter 14

Freddy woke up three times the next morning. The first time was when he dreamed that a pack of wildcats with red eyes was chasing him through an empty house. He hid in a closet to get away from them, but there was one in the closet too. He woke up with a yell. Then he sat up in bed for a while, thinking. At last he decided that it was the ice cream. He had eaten seven helpings at the jail. Or was it eight? He got up and took a little bicarbonate and went back to bed.

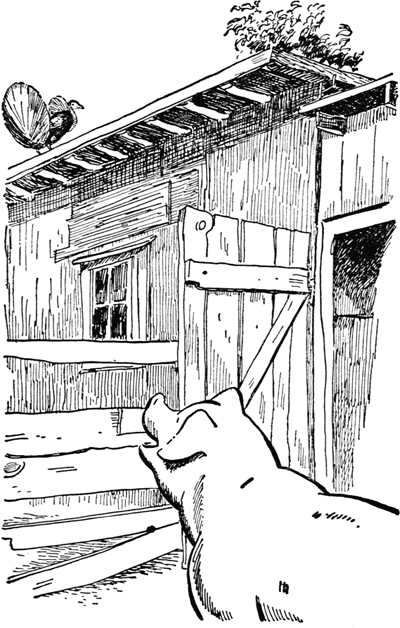

The second time was when Charles crowed, and Freddy merely turned over and went to sleep again. But the third time it was because of the sound of angry voices—Mr. Bean’s and somebody else’s. At first he thought it was the ice cream again, but after a minute he noticed that he was listening with his eyes open, so that it couldn’t be a dream. He jumped up and ran outdoors.

In the barnyard was a dilapidated old buggy, and between the thills stood Zenas Witherspoon’s horse, Jerry, wearing an old straw hat of Mrs. Witherspoon’s. And in the buggy were Mr. Witherspoon and Jimmy.

“Well, I ain’t going to have you giving my boy any of your old castoff clothes, William Bean, and I tell you that straight,” Mr. Witherspoon was saying, and he tossed a bundle at Mr. Bean’s feet. It fell apart as it struck the ground, and Freddy saw that it was the suit and the shoes that Jimmy had won at the tournament.

“I keep tellin’ you, Zenas, you old numbskull, that I didn’t give those duds to your boy,” said Mr. Bean.

“I suppose you won’t deny that they came from your house?” said Mr. Witherspoon.

“Certainly I won’t. Mrs. B., she gave ’em to the animals, to have as prizes in some contest or other. And accordin’ to your boy’s say-so, he won ’em.”

“I did; I won ’em all fair and square,” put in Jimmy sullenly.

“Well, won ’em or not, he ain’t going to wear anybody’s hand-me-downs, not my boy,” shouted Mr. Witherspoon angrily.

“Then I guess he’ll go naked,” drawled Mr. Bean, “for you ain’t ever bought him as much as a toothpick.”

“He don’t wear toothpicks!”

“Well, if he did, you wouldn’t buy him one. You’d make him go out and whittle him one off the fence. My side of the fence, too, I wager. And as for hand-me-downs—what’s he wearing now but some of your old overalls you bought back in nineteen-four? Sure, I can recognize ’em—I bought me some just like that the same year.”

“Well, what of it?” demanded Mr. Witherspoon. “They’re mine, ain’t they? They ain’t charity. I can afford to buy him what he needs.”

“You can,” Mr. Bean retorted, “but you don’t. You’ve got enough money to buy him fifty suits of gold plush, with socks and neckties to match. But you won’t even buy him enough to dress like a human being. You know what the other boys in school call him? The scarecrow. Old Zenas’s scarecrow.”

“Bah!” Mr. Witherspoon sneered. “You’re gettin’ awful enthusiastic about spendin’ somebody else’s money, William. What’s it to you, anyway? He ain’t your boy.”

“It’s nothing to me if you want to starve yourself and go round looking like something that’s been stomped on by elephants,” said Mr. Bean. “It’s nothing to me if, like folks say, you won’t ever stir your coffee with a spoon because you’re afraid of wearing out the cup. But by gravy, when it comes to makin’ a monkey and a hoot-nanny out of your own son, I’m going to tell you what I think of you!”

“And I’ll thank you to tend to your own affairs!” Mr. Witherspoon shouted. “Giddap, Jerry.” And as the old horse started to clump towards the gate: “Fancy suits and shiny shoes!” he sneered. “You put ’em back where they came from. My boy don’t need fallals and fripperies.”

“And you don’t need to holler,” said Mr. Bean. “I ain’t deaf.” He shook his head hopelessly and stooped to pick up the clothes.

But just then Mrs. Bean came out of the door. She was a small round comfortable woman with snapping black eyes, and she walked quickly over to the buggy and said pleasantly: “Good morning, Zenas.”

Mr. Witherspoon had either to stop or run over her, so he pulled up. “Good morning, ma’am,” he said.

She came up to the side of the buggy and said quietly: “Zenas, what are you going to do with all your money?”

Mr. Witherspoon stared at her. “Eh?” he said. “What?”

“You’re a rich man, aren’t you, Zenas?”

“Why …” He paused, then said defiantly: “Yes, ma’am, I am. Is there anything wrong about that?”

“No. Nothing at all. It’s nice to be rich. It’s nice to have people look at you and say: ‘There goes the rich Mr. Witherspoon.’ But there’s one thing you’ve forgotten. You don’t look like a rich man, Zenas. You look like a tramp. And so when people see you, they don’t say: ‘There goes the rich Mr. Witherspoon.’ They say: ‘There goes old Witherspoon. Look at him! I guess he hasn’t got as much money as he makes out.’”

Mr. Witherspoon’s mouth squeezed out a tight smile. “I guess the folks in this part of the country know whether I’m rich or not.”

“Some of them do,” Mrs. Bean said. “Mr. Weezer, at the bank, probably does. But even if Mr. Weezer tells everybody around here that you’re rich, how many of them believe it? ‘Rich!’ they say. ‘Don’t make me laugh! A man that can’t afford even shoes for his family!’”

Mr. Witherspoon flew into a rage. “Can’t afford—can’t afford! Just because I’m smart enough to save my money and not go throwing it around like a lunatic, you think … Why, how do you suppose I made my money? ’Twasn’t by runnin’ out and buyin’ gewgaws with every penny I made.”

“Yes, but it’s made now, Zenas,” Mrs. Bean said. “You’re like a man who starts out to build a house. He lays the foundation and runs up the frame, and he puts in the windows and doors, and he shingles the roof. But when he’s finished, he goes right on. He builds it higher and wider, he adds more rooms and more doors and windows than he could use in a hundred years, and yet he goes right on building. He forgets what he started out to do. A house is a place to live in and enjoy. Well, that’s what money is, too. You don’t just go on making it.”

“Oh, I suppose you’d have me stop, then?” Mr. Witherspoon enquired.

Mr. Bean turned his back on him and walked away. But Mrs. Bean stayed. “Well, Zenas,” she said, “you haven’t answered my question. What are you going to do with all your money?”

Mr. Witherspoon began to look rather upset. “Buildin’ houses, and putting in doors and windows,” he grumbled. “I don’t know what you’re all talking about.”

“You won’t answer,” Mrs. Bean said, “because you aren’t going to do anything with it. Sacks and sacks of it you’ve put away in the bank, and it’s no more use to you than so many sacks of last year’s maple leaves.” She bent down and picked up Adoniram’s suit, which Mr. Bean had left lying there. “I went to school with your wife, Zenas,” she said, shaking the dust off the suit. “Netty Trimble she was then, always gay and full of spirits. I haven’t seen her in ten years. Even after she stopped coming over here, because she didn’t have decent clothes to wear, I used to go over to see her. But I stopped that. She was too ashamed to have me come, ashamed of how poor she had to live. But it wasn’t for herself that she was ashamed, Zenas; it was you she was ashamed of. Had you ever thought of that?”

Mr. Witherspoon shook his head angrily. “I’ve got nothing to be ashamed of. I don’t know why you and William act so mad at me. I’ve always lived on good terms with you as neighbors, haven’t I?”

“You haven’t lived on any terms with us. You’ve been so busy piling up the pennies that you haven’t even known you had neighbors. Well, well; there’s no sense arguing. I don’t expect to change you. I was only hoping you’d let your boy have these clothes. It’s fun for boys to win things. And even though you keep him from having most of the things other boys have, I didn’t suppose you’d be mean enough to keep him from having as cheap a thing as fun.”

Mr. Witherspoon looked glum. “Good land,” he said, “if you make such a point of it as that!… Well, I don’t hold with it, I don’t hold with it at all, but … take those things, boy, if you want ’em,” he growled.

Jimmy jumped out of the buggy. He took the suit from Mrs. Bean, wrapped the shoes in it, and climbed back in.

“Thank you, Zenas.” Mrs. Bean smiled cordially and held out her hand and Mr. Witherspoon took it gingerly. Then she waved to them as they drove off.

“That Zenas!” said Mr. Bean, coming back from the corner of the porch where he had been puffing angrily on his pipe. “If he ever comes into this yard again—!”

“It’s not Zenas I’m worried about,” Mrs. Bean said. “It’s Netty, and that boy. Did you see the boy’s face when he took the things? Trying to hide his happiness from his father. Zenas is always suspicious when any of his folks look happy: he thinks maybe it’s costing him money.”

“Pity about the boy,” Mr. Bean said. “But I don’t know what we can do. I guess I’ll go think it over for a while. Maybe something’ll come to me.” And he started off towards the thinking hole, which he now used quite often.

Freddy, who had listened to the conversation from the corner of the fence, went on into the cow barn, to tell the cows the news the swallow had brought him. They listened to him in silence, and then Mrs. Wiggins said: “Yes, I expect Peter’s right about that wildcat. We’ll have to drive him off. And yet—I’m sorry, in a way. I’d taken rather a fancy to him. You see, Freddy, he dropped in to call yesterday. While you were knocking them flat with your fine clothes at that high society wedding.”

“He called here?” Freddy exclaimed.

“He waited until Mr. Bean was out of the way,” Mrs. Wogus said. “Of course that was only common sense; no farmer wants wildcats around his barns. But as Mac said to us—there are wildcats and wildcats, and he was sure that in time he could break down any foolish prejudice Mr. Bean might have against him. He was really very nice, Freddy. He told us all about his children—he said he was sorry he didn’t have any photographs of them to show us—and really he seems quite a home-loving person—a real family wildcat, if I may use the expression.”

“I guess you may,” said Freddy, “if you don’t ask me to believe it.”

“He likes our neighborhood, too,” said Mrs. Wurzburger. “He said the woods were too remote for bringing up a family. He thought a cultured community like this would be much better for them, and he wondered what we’d think about his coming down here to live.”

“He certainly got the old charm to work on you, didn’t he?” said Freddy. “And I suppose you told him you’d just love it.”

“We didn’t go quite as far as that,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “But I will say we didn’t exactly discourage him. Remember, we hadn’t heard your news about Peter and Joseph then.”

“Who else did he call on?” Freddy asked.

“Alice and Emma,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “And I believe he stopped in to see Henrietta. She wasn’t very cordial—though perhaps that’s only natural. She talked to him from the henhouse roof. But he told us—and her too—that he wants to give a little talk tomorrow afternoon to anybody that cares to come, on ‘The Wildcat as Citizen,’ or ‘The Home Life of the Wildcat,’ or something like that. We thought it might be interesting, since as he said, we farm animals don’t know much about wildcats. He said we’ve got the wrong idea about them; whoever named them ‘wild’ in the first place had done them a great injustice.”

“Quite the gentleman of the old school, isn’t he?” said Freddy. “Well, I guess you can see what he’s up to. Trying to make us think he’d be a good neighbor, so that we won’t object to his bringing his family here to live. And then, when Joseph opens his school, and the pupils begin disappearing, we’ll all say: ‘Oh, it can’t be that nice wildcat who’s making the trouble! Why, he was in here to tea only yesterday afternoon, and such a nice, mild-mannered animal you never saw!”

“I guess you’re right; he’ll have to go,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “But—” she looked hard at Freddy “—you didn’t intend to ask us to drive him away, did you?”

“I don’t know who else could tackle the job,” Freddy said.

Mrs. Wiggins shook her head. “We wouldn’t mind tackling him in the open, where we can swing our horns. But to go into the woods after him—thank you kindly!” And Mrs. Wogus and Mrs. Wurzburger shook their heads too. “Stumbling around, getting hooked in vines and creepers, and him on a limb overhead, like as not, just waiting to spring until we get stuck tight.”

“How about Jacob?” said Mrs. Wiggins. “He’s helped us before.”

“Jacob!” Freddy perked up. “By George, I think you’re right. I’ll go see him right away.”

Jacob was a wasp who lived in one of a row of wasp apartments under the eaves of the barn. When Freddy called to him he flew down and lit on the pig’s nose. He said: “I’d be delighted to help you, Freddy, but there’s the State Wasps’ Convention this week down at Binghamton and—well, you know how it is; maybe they won’t call on me for a speech at all, but after all I’m pretty prominent in a way—I mean I’ve won all those cross-country racing prizes and so on, and if they did call on me for a few words, I ought to have something ready. I’ve been throwing a few ideas together and I’ve got to whip them into shape. But if you can wait until Monday, I’ll rout out some of the boys and we’ll take care of that wildcat for you.”

There seemed to be nothing to do but to wait. Freddy went back to the pig pen but he was just going in the door when he noticed a very strange looking bird sitting on the roof. It had a sort of ruff around its neck of stiff white feathers, and its tail was a red, white and blue fan. It was certainly very striking looking, and Freddy was about to call to it when it flew down and lit beside him, and he saw that it was Mrs. Popinjay.

He noticed a very strange-looking bird sitting on the roof.

“My goodness,” he said, “you’ve certainly been out spending J. J.’s hard earned money, Mrs. P. Not that it isn’t very becoming—very fetching, in fact.”

Mrs. Popinjay cocked her head coquettishly. “Oh, Freddy! What things you say! But you ought to see some of the others. A lot of us have been down to Centerboro and Miss Peebles has been dressing us up. Then she puts us in the window, just as she did J. J., and sells us as hats. She got the idea from Mrs. Church. So many people admired Mrs. Church’s live popinjay hat at the wedding, and they all came to Miss Peebles to see if they couldn’t get one like it. So Miss Peebles spoke to J. J. and told him to bring some of his friends in to be trimmed. Of course she doesn’t really sell us; we’re just hired out. For instance, I’m Mrs. Weezer’s hat now, and when she’s going somewhere special, like a church supper or a card party, I go down so she can wear me.”

“Miss Peebles hasn’t wasted much time,” Freddy said. “The wedding was only yesterday.”

“Her store has been crowded all day long,” said Mrs. Popinjay. “I’ll bet she’s trimmed twenty bird hats today.”

“But what does she get out of it?”

“We give her half of what we make,” said the robin. “I get fifty cents for every appearance, and half of that goes to Miss Peebles.”

Freddy thought that was fair enough. “But that’s big money for a bird,” he said. “Of course you’ll want to spend some of it on a good time, but do put some aside for a rainy day. Come down to the First Animal Bank when you get the time and let me explain our Savings and Loan Service to you.”

Mrs. Popinjay chirped with amusement. “You’re getting as bad as Mr. Weezer,” she said. “Every nickel you see you want to roll it right into your bank. Well, I’ll be seeing you!” And with a flirt of her feathers she flew off.

“My goodness,” said Freddy, talking things over with Jinx a little later, “I don’t know whether all these fine clothes are such a good thing after all. That Mrs. Popinjay used to be such a quiet, modest little bird, but since she’s got all trimmed up she’s—well, she kind of poses all the time, as if she thought everybody was looking at her.”

“Yeah, I know,” said Jinx. “Kind of silly. It’s the same with her husband. When he was just plain Mr. Pomeroy I had nothing to say, for or against him, and that’s the way folks you don’t know very well ought to be. But since he got those fancy tail feathers it’s all strut and waggle. I’ve watched him. If a strange bird comes along, up he goes. ‘I’m J. J. Popinjay; maybe you’ve heard of me.’ Then he looks at ’em down his beak through those little spectacles, and the stranger kind of wilts. ‘Yes, sir; no, sir.’” Jinx held a paw up and examined his claws thoughtfully. “Some day I’m going to catch that bird on the ground, and then we’ll see what he’s like when he’s trimmed down to size again.”

“I’m just wondering,” said Freddy, “if we made a mistake in getting those new clothes for Jimmy.”

“You mean you wonder if they’ll make him into a popinjay too? I wouldn’t worry. Old Zenas will take care of that.”

Freddy shook his head. “They say fine feathers make fine birds. But I’m afraid they just make stuck-up ones. Well, we’ll have to wait and see.”