Many large firms are organized into divisions or profit centers to facilitate the efficient operation of the firm. The decentralization of decision making in this way is considered to have beneficial impact on the firm’s overall efficiency and profitability, since each division manager is judged by the profit performance of his or her division or profit center. A problem can arise, however, when one division or profit center supplies a component product (or intermediate product) to another division or profit center that uses this intermediate product as the basis for the firm’s finished product, which is sold to consumers. This transaction is essentially internal to the firm and does not take place in the market for that intermediate product, if indeed there is a market for it. If the “transfer” price is set at a relatively high level, the supplying division will make more profits and the buying division less, presuming there is competition of some sort in the market for the finished product. If the transfer price is set at a relatively low level, the opposite will prevail. The firm as a whole will wish to set the transfer price at a level which serves to maximize the profit of the firm as a whole, rather than at some arbitrary or negotiated level that may not best serve the firm’s objective.

We shall analyze the transfer pricing problem under three scenarios, first considering the case where there is no external market for the intermediate product, then considering the existence of a purely competitive external market for the intermediate

product, and finally considering the existence of an imperfectly competitive market for the intermediate product.

Transfer Pricing with No External Market. The marginalist rule, that marginal cost equals marginal revenue, determines the profit-maximizing output and price level for the firm as a whole. But if the firm has two divisions, for example, its overall marginal cost at any output level will be the sum of the marginal costs in its two divisions. Suppose a firm has two divisions, A and B. The intermediate product is produced in division A, and then packaged and marketed by division B. We suppose that each division has an upward-sloping marginal cost curve, as shown in Figure 9A-6. The vertical sum of these two MC curves is shown as the MC f curve, and the firm maximizes profit at the price P* and output level Q*.

What transfer price should be established to induce division A to produce exactly the profit-maximizing output of the intermediate product? Similarly, what transfer price will induce division B to set the market price at the level P* such that the firm’s profits are maximized? In Figure 9A-6 we show the optimal transfer price as P T , chosen to equal division A’s marginal cost at output level Q*. As a result, division A faces a horizontal demand curve at the transfer price—it can sell as much as it wants to at that price. However, it will only want to produce Q* units, since its marginal cost (MC^) equals its marginal revenue (MR^) at that output level. Thus setting the transfer price at the level P T induces division A to produce and supply exactly the optimal amount.

From the viewpoint of division B, the net marginal revenue (NMR) from the sale of the intermediate product is equal to MR f — MC g , or the market marginal revenue minus division B’s marginal cost. At output/sales level Q*, note that NMR = MC^ (because MR f = MC f at output Q*, hence MR f — MC B = MC/r — MC S = MC^).

FIGURE 9A-6. Transfer Pricing with No External Market

That is, the marketing division’s net marginal revenue equals the marginal cost of the intermediate product that it buys from division A, which is in turn is equal to the transfer price. Thus division B maximizes its profits by setting market price P* and output/sales level Q*. At any other price and output combination in the market for the finished product, division B’s NMR would either exceed or fall short of the transfer price (its effective marginal cost of the intermediate product), and its divisional profit would not be maximized.

Thus establishing the transfer price at the level P T provides the appropriate incentives for both divisions to produce and sell the firm’s profit-maximizing output level Q*. Each division maximizes its profits by producing Q* units, and the overall firm’s profits are also maximized. Any other transfer price may have higher profits for either division A or B, but would have lower profit for the firm as a whole, not to mention a shortage or surplus of the intermediate product.

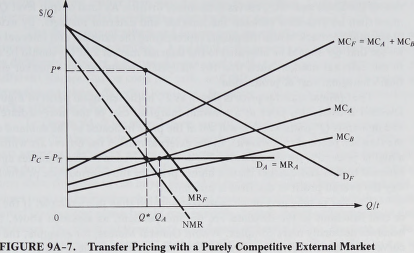

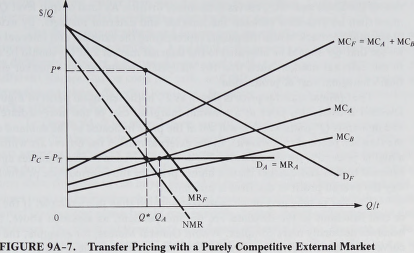

Transfer Pricing with a Purely Competitive External Market. Now suppose that the intermediate product is available from other suppliers as well as division A. Moreover, division A’s product is identical to that of other suppliers. There will be a market price for the intermediate product determined by the forces of supply and demand in that external market. In this case the transfer price must be set equal to the market price for the intermediate product. If it is set higher, division B will prefer to buy from the external market rather than from division A. If the transfer price is set below the external market price, division A will prefer to sell to the external market rather than to division B. If, at the transfer price (equal to the market price), division A wants to produce more than division B wishes to purchase, it can sell the balance in the external market. Conversely, if division B wants to purchase more than division A wishes to produce, it can buy the remainder in the external market.

In Figure 9A-7 we show the transfer price set at the external market price P c . Note that division A will wish to produce Qa units, such that MC^ = MR^. Division B will demand only Q* units, since NMR = MR f — MC B = P r at that output level. Thus division A will sell the remainder, shown by the distance Qa — Q*, in the external market for the intermediate product. Had the competitive external market price been lower, such that Q A < Q*, division B would have purchased some from division A and the remainder from the external market.

Transfer Pricing with an Imperfectly Competitive External Market. Now we suppose that the intermediate products are not identical across firms, and thus each supplier to the external market faces a downward-sloping demand curve in that market. In Figure 9A-8 we show the demand and marginal revenue curves for the external market in the middle panel of the figure. In the left-hand panel we show the net marginal revenue (NMR) curve for (the marketing) division B of the firm, which is responsible for setting the market price and output level in the market for the finished product. Division A again has two markets for its output—it can sell to either division B or it can sell to the external market. However, since the elasticities of demand are different

in these two markets in this case, division A will find it profitable to practice price discrimination between the two markets.

The analysis proceeds as in the third-degree price discrimination case. The firm will sum horizontally the marginal revenue from its markets, and equate the EMR with its marginal cost of production MC^,. But note that from the firm’s point of view it must consider only the net marginal revenue from the internal market (sales to division B), since otherwise it would be ignoring division B’s marginal cost. The intersec-

Internal market

External market

Division A

FIGURE 9A-8. Transfer Pricing with Imperfectly Competitive External Market

402 Pricing Analysis and Decisions

tion of the EMR and MC^ curves determines division A’s total output level Qa , which must then be allocated between the internal and external markets. By extending a horizontal line back across the panels representing the external and internal markets, we see that Q* should be allocated to the internal market and Q E should be allocated to the external market, such that the marginal revenue in each market equals the firm’s marginal cost of production.

The optimal transfer price is shown as P T in the left-hand panel of Figure 9A-8. Division B treats this price as a constant marginal cost of the intermediate product and demands Q* units which it will sell at the price indicated by the demand curve for the finished product (not shown). In the external market the buyers are willing to pay a higher price, P E , for the quantity Q E , and thus division A discriminates against the external buyers and charges them a higher price for the intermediate product. In this way the overall profit of the firm is maximized.

Transfer pricing gets much more complicated than this example. If the demand or cost functions of the divisions are not independent, as assumed above, the issue becomes decidedly more complex. Within General Motors, for example, the demand curves of Chevrolet, Buick, and a third division producing electrical components are interdependent because their products are either substitutes or complements for each other. On the cost side, if they compete in the same input markets, their cost functions may well be interdependent as well. Multinational firms, with divisions or profit centers in different countries, must also consider the tax rates, import and export duties, and a variety of other issues that are involved. The interested reader is referred to the literature on transfer pricing for these extensions. 2