“PREPARE FOR WAR” WAS THE CLARION CALL OF THE FEDERALIST PARTY. NEITHER the Federalists nor the Republicans differed over the wider objectives of American national policy during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Both political parties agreed that the highest national objectives should be economic prosperity at home while protecting the nation's rights and maintaining its neutrality abroad. What divided these political factions was the best way to achieve those ends during the series of conflicts that marked the period from 1793 to 1815.

“War is a great calamity,” said Federalist Connecticut US Congressman Benjamin Tallmadge, “and the surest way to avoid it, is to be prepared for it.” As a result, the Federalists put in place a program of financial and military preparedness in the 1790s. Closely aligned with fiscal reforms, the Federalists expanded the nation's armed forces. The standing peacetime army was increased from 840 officers and enlisted men in 1789, to 5,400 personnel by 1801. The latter year saw the navy, which had been completely dismantled at the conclusion of the American War of Independence, provided with 13 frigates in service as well as six ships-of-the-line under various stages of construction. Rounding out their defense measures, the Federalists allotted over $1 million for the protection of port cities from attack from the sea.

In the diplomatic field, the Federalists hoped to bolster national defense by advancing a pro-British foreign policy. They surmised that British naval power was both a potential threat and a shield to American trade. To neutralize the former and take advantage of the latter they pushed through Congress the Jay Treaty of 1794, an Anglo-American agreement that regulated commerce between the two nations as well as defined the rights of neutrals in time of war. The treaty stimulated an explosion of US export trade from $33 million in the year it was signed, to $94 million by 1801. An additional benefit derived from the treaty was that America gained a cordial relationship with the only European power that could menace its shores and seaborne commerce.

Despite the real prosperity Federalist policies had garnered, the party met a decisive defeat in the national election of 1800. Heavy taxation, resulting in a large national debt to support the country's defense, the public's fear of a permanent military establishment, an attempt to silence political opposition through anti-sedition legislation, a pro-British foreign policy— which alienated many Americans who still felt the effects of the revolt against the mother country—doomed the Federalists and their programs at the polls.

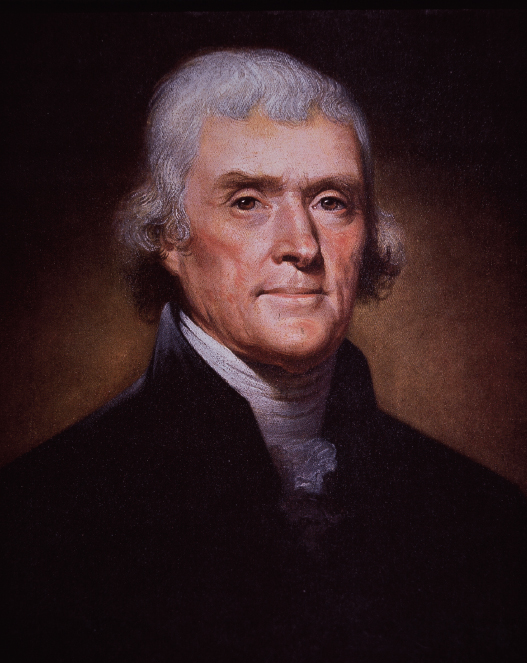

With their victory in the election of 1800, the Republican Party, under the new President Thomas Jefferson, was determined to reverse the Federalist agenda that had been in place for the past decade. All the Federalist economic policies, such as internal taxes and infrastructure spending, were rolled back in the name of economizing and paying down the national debt.

The national defense establishment did not escape the new cost cutting measures either. The peacetime army was reduced in 1802 from 5,400 to 3,300 officers and enlisted men. The result was a severe lack of training for the men and an almost nonexistent level of professionalism in the officer corps. Senior officer slots were filled with Republican political appointees with no military schooling, their only qualification being that they were loyal to the Republican Party. General Winfield Scott observed that most were “imbeciles and ignoramuses.” By 1810, the incompetence of the army's top brass was so evident and demoralizing to the rank and file soldier that one Republican politician, Nathaniel Macon, opined that “The state of that Army is enough to make any man who has the smallest love of country wish to get rid of it.”

Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States, 1801–09. During his administration, tensions rose between the US and Britain. Portrait by Rembrandt Peale.

The navy got no better treatment from the Republicans. Their mantra, according to Republican Samuel McKee, was that a nation with a navy was a nation constantly engaged in war. To prevent that, and with an eye toward limiting government expenditures, construction of all capital ships was halted, and only seven frigates were retained in service. In lieu of a viable navy, the Republican government spent $2.8 million between 1801 and 1812 on coastal defense installations. But without a reasonably sized mobile fleet, the cities of the eastern seaboard remained exposed to enemy warships and amphibious forces.

Distrustful of a standing army and navy, fearing that these fostered special interest groups that presented a danger to government, the Jefferson administration felt the need to gut the nation's defense establishment. In its opinion the most reliable and patriotic defenders of the country would not be expensive and permanently maintained regular soldiers and sailors, but state militia serving on land, and privateers on the ocean. Besides, both being democratic in character, they would pose no threat to government institutions. Equally important, they were cheap, not having to be paid until called to service, with monetary outlays ceasing when they were no longer required. The fact that, on the whole, the militia was ill-trained, poorly equipped, and miserably led, while privateers could not fight enemy warships, break hostile blockades, or protect friendly coastal centers, seemed not to concern Republican leaders. What did matter most to them was economic retrenchment, the basic Republican Party political tenet that got them into office, and in their minds, would keep them there.

The war between Great Britain and Napoleonic France resumed at the end of the 1801– 1803 Peace of Amiens. During that short-lived truce, America's trade advantages dropped by almost one half. The resumption of conflict between the two Great Powers saw American overseas commerce climb as she again became one of the largest carriers of goods between the western hemisphere and Europe. Britain's remarkable indulgence toward the increasing US-Atlantic trade dominance prompted James Monroe, the American minister to London, to report to his government in 1804 that: “The truth is that our commerce never enjoyed in any war, as much freedom, and indeed favor from this govt [British] as it now does.” However, by October of the next year, Monroe was complaining that the British were attempting “to subject our commerce at present and hereafter to every restraint in their power.” What had changed Britain's attitude toward American trade practices since Monroe's initial remarks of 1804?

British authorities had become increasingly alarmed at what they detected as unfair, even fraudulent, American trade activities and had started to strictly enforce Great Britain's maritime doctrine known as the Rule of 1756. The Rule stated that trade closed to a neutral nation in time of peace could not be opened in time of war. Its purpose was to prevent US merchants from freighting goods between France and her West Indian colonies when French vessels could not get to sea. But American shippers were able to get around the Rule by first stopping at an American port prior to continuing to or from the French West Indies, thus transforming direct trade between France and her overseas possessions into a triangular one.

Determined both to regulate and grab a share of the lucrative trade the US was reaping through the French-West Indies commercial traffic, the British declared that they would no longer allow the American practice of funneling goods through US ports as a way to evade the Rule of 1756. Soon Britain began seizing American merchant craft engaged in the re-export business, resulting in crippling financial losses to Yankee ocean commerce. British interference continued through mid-1806 until it was discontinued, but the harm to American commercial interests had been done, and the resentment by the Americans toward their British cousins did not abate.

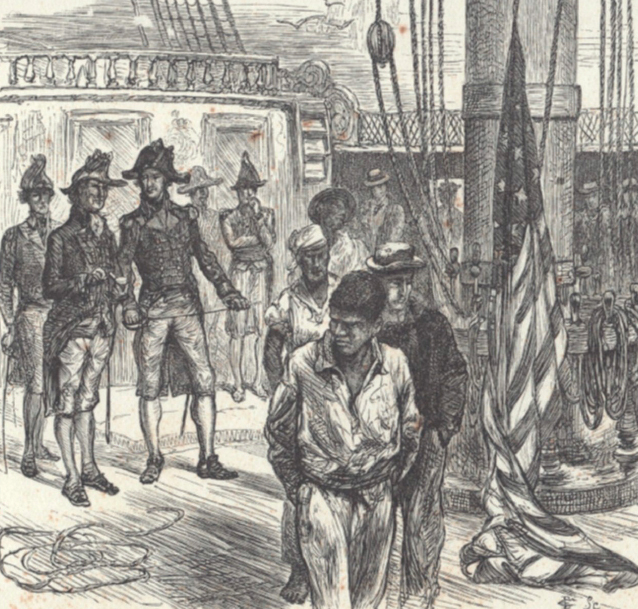

Along with the issue of the rights of neutrals to freely trade during wartime, impressments—the British practice of taking American seaman by force, claiming they were British subjects, from American ships on the high seas—caused great bitterness and friction between the two nations. During the period 1803–1812, some 6,000 American citizens were forced into British service as a result of impressment. This practice was deemed essential by Britain as the only way to maintain crew strength in the Royal Navy during its life-and-death struggle with France.

In addition to the questions of rights of neutrals to trade, and impressment, America and Great Britain argued over several other maritime issues: British methods of imposing internationally recognized blockades; the definition of what was contraband that could be seized by a belligerent from a neutral; and the common practice of British warships violating American territorial waters.

In an attempt to resolve many of these differences, Great Britain and the United States forged an agreement—the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty of 1806—that went a long way toward satisfying American concerns about securing their commercial rights. But President Jefferson considered the British commitments in the treaty minor, and since it did not include a British promise to end impressment completely, he refused to send the treaty to the US Senate for ratification. His inaction resulted in a further strain of American-British relations.

The period after the rejection of the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty witnessed a rapid deterioration of American-British relations. The first critical episode in that downward spiral came in the form of the Chesapeake affair. On June 22, 1807, the American frigate USS Chesapeake, sailing for the Mediterranean Sea and completely unprepared for combat, was attacked by HMS Leopard. The latter's intent was to capture British deserters assumed to be on board the American ship. The scheme was initiated despite the fact that the Royal Navy did not claim the right to search for or impress men on neutral warships. When the American commander refused to allow the British to board and search his craft, the Leopard opened fire, killing three and wounding 18 others. Devastated by the assault, the US ship struck her colors and permitted the British to remove the alleged deserters. Despite an offer of reparations by Britain, and a return of those sailors taken from the Chesapeake, the controversy dragged on until 1811 and continued to contribute to the growing animosity between the United States and His Britannic Majesty's government.

Impressment was one of the causes of the War of 1812. Here, American sailors are forcibly taken from the USS Chesapeake following a clash with the British frigate HMS Leopard in 1807.

Hard on the heels of the Chesapeake affair, another act by the British surfaced to complicate the already strained relations between the American Republic and British Empire. British Orders in Council—a series of dictates issued throughout 1807 designed to counter Napoleon's Berlin Decree of 1806—came into affect. The French declaration proclaimed that the British Isles were to be in a state of isolation by land and sea. The decree prohibited all commerce with British ports, while goods from either British or her colonial ports were subject to seizure. In response, the Orders in Council banned trade from ports controlled by Britain's enemies. Later, they compelled all neutral shipping to stop at British harbors to be searched, and where they were subject to capture and confiscation. In addition, they required all neutral merchants to pay duties and apply for licenses issued by Britain in order to carry on trade with the Continent.

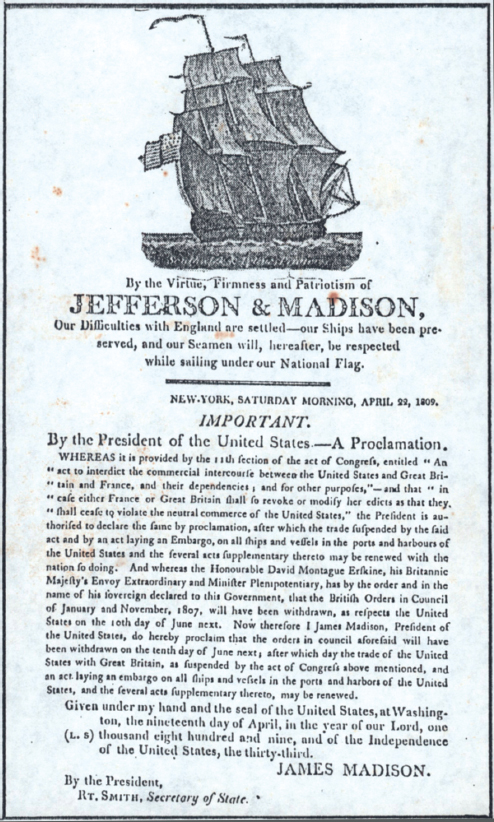

Republican broadside published in 1809, claiming that Britain would respect sailors and ships sailing under the American flag.

Responding to the Orders, France promulgated the Milan Decree in December 1807, extending to neutrals the embargo on products destined for Great Britain. American trade was thus caught in a vice formed by British and French trade restrictions. The cost to the young nation in lost shipping was significant. Between 1803 and 1807, 528 American-flagged ships were seized by the British and 206 by the French.

President Jefferson and Congress, in a flawed attempt to strike back at Britain, declared an embargo prohibiting all US ships from trading with Europe, and banned the importation of goods manufactured in England. This plan to get the British to relax her trade controls on neutral shipping was unsuccessful and caused more economic suffering in the United States than to its intended target. The Embargo Act of 1807 drove the nation into a severe depression as exports dropped from $108 million in 1807 to $22 million in 1808, which resulted in 55,000 seamen and 100,000 other workers thrown out of work.

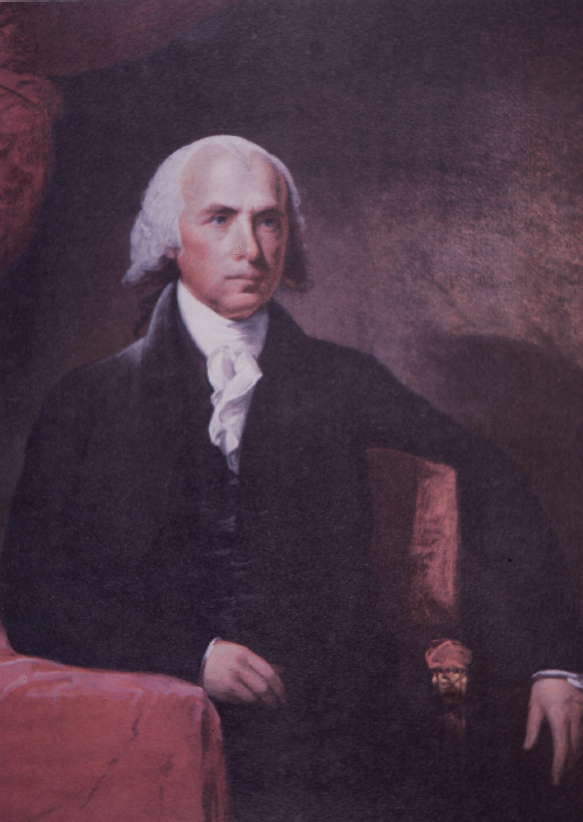

James Madison, 4th President of the United States from 1809 and during the War of 1812. Portrait by Gilbert Stuart.

In 1809, the Republican James Madison became President. In that same year, the United States Congress replaced the failed Embargo Act with the Non-Intercourse Act which reopened trade with all nations except Britain and France, but, like the Embargo Act, it did not gain concessions from the two belligerents. Britain issued additional Orders in Council in 1809 that further injured American trade. In 1810, Napoleon offered to lift French restrictions on American shipping if the British would abolish their series of Orders in Council. Instead, London in 1811 issued new edicts that curtailed the Yankees' ability to trade with the West Indies, and placed heavy levies on all goods entering the United States.

As the non-importation law continued to degrade US-British relations, events in 1811 moved the countries closer to war. The first involved the Little Belt Incident—in essence the Chesapeake affair in reverse. On May 16, the large American frigate USS President clashed with the much smaller British sloop HMS Little Belt. The resulting gunfight left nine killed and 23 wounded among the British crew. An outraged British public called for revenge, even if it meant war. “The blood of our murdered countrymen must be avenged,” said the London Courier newspaper. “The conduct of America leaves us no alternative.” On the other hand, the Americans felt that the stain on their national honor caused by the attack on the Chesapeake four years earlier had been properly wiped clean.

As the Little Belt affair pushed the two nations closer to war, America's attention was diverted from maritime disputes with Great Britain to her security and territorial expansion interests in the Old Northwest (now including Ohio, Michigan and Indiana). Around the heavily forested Great Lakes, about 50,000 Native Americans occupied the land as the Americans relentlessly pushed their settlements into the area. The Indians relied on the British in Canada to help them resist the American encroachment by supplying them with weapons, while the British counted on the natives to aid them in defending Canada in event of war with the United States. “The British cannot hold Upper Canada without the assistance of the Indians,” concluded Michigan's governor William Hull in March 1811, but the “Indians cannot conduct a war without the assistance of a civilized nation.”

Although the British counseled restraint to their Indian allies, the United States regarded the Indians as pawns in an insidious British plot to ravage the frontier. While the British viewed the natives as autonomous peoples dwelling between the British Empire and the American Republic, and therefore free to make their own alliances, the American view was that the Native Americans should be US dependents, living within a fixed boundary separating British from American sovereignty. Furthermore, the Jefferson administration had hoped to absorb the Indians into American society by transforming them from hunter-gatherers to farmers without tribal identities.

This transformation would not only wean the Indians from their reliance on martial aid from the British, but also make it easier for American settlers to obtain Indian lands, since sedentary Indian farmers would need far less land than roaming hunters. On Jefferson's orders, the territorial governors of Indiana and Michigan had pressured the tribesmen to secede millions of acres for mere pennies each. William Henry Harrison of Indiana was especially relentless in this regard. His negotiations of land cession agreements with chiefs of minor tribes, without getting approval for the sale from all the Indian leaders as required, was an open breach of prior US-Indian treaties. The result was outraged young native warriors who sought redress for their grievances against the United States through force of arms.

They turned for leadership to the charismatic Shawnee warrior Tecumseh—also known as “Shooting Star”—renowned for his statesmanship and moderation. While the 44-year-old Tecumseh worked to forge bonds of unity among the Indians of the Old Northwest, his brother, Tenskwatawa (“the Prophet”), became the spiritual head of the growing Indian coalition—an Indian confederacy Tecumseh hoped would stretch from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, forming a buffer state between Canada and the eastern United States.

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa met Harrison in August 1810 to lodge a complaint about the blatantly illegal land transactions Harrison had conducted with the Indians. This meeting, and further complaints, produced no results. Rejecting Harrison's treaties, the brothers vowed armed resistance and gathered 1,000 warriors at their main village of Prophetstown, also known as Tippecanoe, in the Wabash Valley of northern Indiana. In November 1811, Harrison marched against them with 1,000 US regular soldiers and volunteer frontiersmen. The US army made camp about two miles from the village. On November 7, it was attacked on orders from the Prophet in a surprise assault by 600 Indian braves. Tecumseh was not at Prophetstown at the time, having travelled to consult with other tribes further south.

The battle of Tippecanoe turned into a vicious hand-to-hand affair that mauled Harrison's force and cost it 68 killed and 126 wounded, but ultimately proved an American victory. The Indians, losing about 100 warriors in the fight, abandoned Prophetstown, which was burned by the Americans. Harrison then led his command back to its base at Vincennes. On his return from the south, Tecumseh gathered the remnants of his followers and joined the British at Amherstburg.

James Monroe, Secretary of State during Madison administration, later 5th President of the United States.

The battle had destroyed the nucleus of Tecumseh's nascent Indian confederacy but did not stop Indian depredations on the frontier. The Indians, with aid from the British, continued to raid over the following winter and spring. An editorial in the Lexington Reporter expressed the general sentiment of the frontier: “The British are the principal [force]— the Indians only hired assassins.” Politicians in Washington pointed to unrest on the border as another example of British duplicity and the grave danger it presented to the population of the trans-Appalachian west, thundering that it could only be extinguished by going to war with Britain.

American territorial ambitions were not confined to the Northwest. Jefferson had claimed all through his Presidency that Spanish West Florida had been part of the Louisiana Purchase, a proposition denied by France. A US-inspired revolution in September 1810 saw the brief occupation of West Florida. US troops took over Spanish East Florida in March of 1812 and left troops in the area even after President Madison, in April of that year, denied any responsibility for the incursion. Notwithstanding the President's denial in the affair, the expanding young nation would soon turn its eyes once more to Florida.

Tecumseh, chief of the Shawnee tribe, allied himself with the British against the Americans. Portrayed here wearing a British tunic and medal.

Apart from maritime issues, such as the rights of neutrals and impressment, the Indian problem and the quest for new land, America's most significant impetus for war seems to have been voiced by William Cobbett. An English journalist and political reformer, Cobbett had resided in Philadelphia from 1793 to 1800 and had become a good judge of the American character. In his opinion, the real cause for the outbreak of war between America and Britain was that, “There seemed to be wanting just such a war as this to complete the separation of England from America; and to make the latter feel that she had no safety against the former but in the arms of her free citizens.”

In other words, according to Cobbett, the War of 1812 would assure the legacy and results of the War of American Independence by revealing to the world that the United States was free, independent, self-reliant, capable, and a power to be reckoned with among the nations.

Tenskwatawa, also known as “the Prophet,” was the brother of Tecumseh, and spiritual head of the Indian coalition against the Americans.

In 1810, Chief Tecumseh defies William Henry Harrison, Governor of Indiana Territory, and declares he will seek an alliance with the British.

Contemporary cartoon depicting a disloyal Federalist editor failing to impress three Americans sailors not to go to war against Britain.

The Twelfth Congress, known to history as the War Congress, convened on November 4, 1811. Although the Republicans held commanding majorities in the United States House of Representatives and Senate, they lacked effective leadership and were racked by factionalism. This condition was dramatically transformed by the presence of a new group of 11 young Republicans called the War Hawks. Under their leader, Henry Clay from Kentucky, key House committees were packed with War Hawks or their supporters, and House rules were interpreted in order to advance their pro-war movement. The War Hawks brought the backbenchers—mostly Republicans—in both the House and Senate on board in support of their desire for a war with Great Britain, to finally resolve the tensions that had plagued America over the previous ten years.

The final decision for war was not taken up until June 1812, but major congressional proposals for preparation for conflict were passed earlier that year. They included expanding the Regular Army to 35,000 recruits, raising a 50,000 man volunteer force, refitting warships, arming all merchant vessels, and appropriating $500,000 for coastal defense. To finance the coming struggle, the government was authorized to borrow $11 million, though any taxes needed to support the conflict would not be raised until war had been declared.

On June 18, 1812, President James Madison signed the war bill. It passed the Senate by a vote of 19 to 13, and in the House 79 to 49. Hostilities between the United States of America and Great Britain had officially begun. It is quite possible that the measure was intended merely to wring concessions from the British, not start a full-blown conflict. The American government knew of the fight for survival the British were engaged in with Napoleon, as well as the vulnerability of Canada to an American invasion. The Madison administration appeared to be using the declaration of war as a negotiating tool when the President and his Secretary of State, James Monroe, laid out the American terms for peace to the British shortly after war was declared.

The British government was on notice of American preparations for war, but London, in the words of the Lord Castlereagh, British Foreign Secretary, viewed these acts of “belligerence in the United States as to be no more than party maneuvering.” But, as the middle of 1812 approached, the British became more alarmed at America's militaristic determination, and, in an effort to appease their former colonies repealed their Orders in Council on June 21.

News of the American declaration of war reached Great Britain on July 30, 1812. The British were reluctant to respond with martial measures of their own since they were confident that news of the doing away with the Orders in Council would induce America to reverse its decision. Their hopes were dashed with the American demand, and the British refusal, to suspend the practice of impressment. On October 13, His Majesty's Government issued Orders in Council, in effect a declaration of war, authorizing “general reprisals against the ships, goods, and citizens of the United States.”

The British government and people were outraged at America's action precipitating war. In their view their struggle with France was not only for national survival, but one championing liberty against French tyranny, which America should be supporting, not jeopardizing, by going to war with Britain. John W. Croker, Secretary of the British Admiralty, expressed the sense of sadness and betrayal felt in his country at the actions taken by America. “There are now two free nations,” he wrote, “Great Britain and America—let the latter be beware how she raises her parricidal hand against the parent country; her trade and liberty cannot long survive the downfall of British commerce and British freedom. If the citadel [Britain] which now encloses and protects all that remains of European liberty be stormed, what shall defend the American union from the inroads of the despot [Napoleon]?”

John Calhoun of South Louisiana, one of the Republican “War Hawks” who pushed for war against Britain in 1812.

In June 1812, President Madison and Congress sounded the call to arms. It remained to be seen how that summons would be answered by the American nation—and responded to by an enemy as powerful as the British.