IN AUGUST 1812, THOMAS JEFFERSON WROTE TO A FRIEND EXPRESSING THE LONG-standing American belief that Canada could be easily plucked from the British Imperial lion's paw. “The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec,” he wrote, “will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us experience for the attack on Halifax the next, and the final expulsion of England from the American continent.”

Others doubted the notion of a quick occupation of Canada by the United States. The Yankee, a Boston newspaper, complained in 1812 that the belief that the British colony would be rapidly overcome by America's might “had taken deep root in Washington … and will not be easily exterminated.” It went on to question the supposition “that the show of an army, and a few well directed proclamations would unnerve the arm of resistance, and make conquest and reconciliation synonymous.” By the time Jefferson penned his August letter, it was already apparent that the United States was not going to succeed in achieving an easy victory in waging what many Americans were calling a “second war for independence.” Indeed, the War of 1812 did not turn out to be the romp Jefferson had envisaged.

“The moment chosen for the war,” wrote James Madison in 1827, “would, therefore, have been well chosen with a reference to the French expedition against Russia; and although not so chosen, the coincidence between the war and the expedition promised at the time to be as it was fortuitous.” It is true that Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812 was the linchpin for America's war strategy against Britain. In May 1812, 650,000 French and allied soldiers concentrated on Russia's border. The world expected the confrontation to commence that summer and all were convinced that France would be victorious; the Madison administration used the invasion as an opportunity to declare war on the British.

Critics of the administration's military establishment and policies, which they derisively termed “a defense worthy of Republicans,” pointed out that the United States was in no condition to fight Great Britain alone. A puny navy could not challenge the Royal Navy, and an army that was small, scattered around the country, under-trained and poorly led, had no chance of waging a successful campaign. But the government in Washington felt confident that the looming Franco-Russian conflict would be just the diversion America needed to aid her in achieving a favorable settlement of her grievances against Britain.

Madison's strategy for a land war called for an American incursion into Canada just as Napoleon's forces marched into Russia. Madison reasoned that after Russia had been subdued by the French, the British would be driven out of Spain and Portugal, and the United Kingdom itself threatened by a Gallic invasion force. As a result, the British would have to keep the bulk of their army and navy at home to ward off the enemy menace, leaving Canada's defenses weak and vulnerable.

At sea, Madison anticipated that the miniscule US Navy would early on be destroyed, captured, or shut-up in American ports by the Royal Navy. He toyed with keeping the few warships the country had in harbor and employing them as floating batteries. However, he changed his tune after being confronted by a number of his senior naval officers. Instead of acting as immobile gun emplacements, the government sanctioned their use as commerce raiders. An additional element of the American naval strategy would be to unleash hundreds of privateers, authorized under letters of marque, to hunt down enemy merchant vessels in an attempt to ruin Britain's seagoing trade, thus pressuring her to come to the peace table.

Napoleon's invasion of Russia in June 1812 was to be the linchpin for America's war strategy against Britain. A French victory, believed the Madison administration, would divert Britain's military resources.

On the economic front, the United States deployed trade restrictions, collectively known as the restrictive system, composed of embargoes, non-importation and non-intercourse laws. Although this economic coercion system failed in its goal in the years prior to the altercation with Britain, it was revived and put in place during the War of 1812. This is not surprising considering that President Madison had been the chief architect of the restrictive system during the Jefferson administration. The restrictive system proved ineffective, however, since Britain's economy was far less dependent on American commerce than the Republicans imagined, and widespread illegal trading between US citizens and Britain during the war—that is, smuggling—flourished across every American border and coastline.

The United States also waged a diplomatic effort to influence the course of the war. Hoping to prove that all Americans wanted were concessions regarding maritime issues, not war, the Madison administration gave the British hints of its true intentions and desires. Shortly after declaring war, the British Ambassador to the United States, Augustus J. Foster, was sent terms for peace. Critically, the US never clarified its position on Canada during the war, whether it intended to annex the colony or not. However, it seems highly unlikely that once taken, America would ever relinquish all of Canada; the political backlash in the country would have swept the Republicans from office. Furthermore, to promote peace with Britain, Madison wrote to his ambassador in Paris to spread the notion that if the United States and Britain could resolve their differences, “the full tide of indignation with which the [American] public mind here is boiling will be directed against France. War [against France] will be called for by the nation almost una voce.” The reason for this paradoxical stance—starting the war, but trying to end it as soon as it began—lay in the fact that American success in the conflict always relied on her ability to successfully carry the fight to the enemy, and in that regard she fell woefully short during the entire conflict.

With a strategy determined, the United States turned to the instruments needed to carry out its implementation: the regular army, the militia, the navy and privateers. Except for the navy, all would prove entirely inadequate for the martial task America had set for itself. The seeds for this condition had been planted years before.

Speaking during his 1801 inaugural address, President Thomas Jefferson declared that “a well-disciplined militia, [was] our best reliance in peace, and for the first moments of war, till regulars may relieve them …” With these words, the nation's chief executive assured the country that it did not need a standing army and that its safety would be realized by a citizenry trained and organized in arms. When he came to the presidency, the regular United States Army had a strength of 248 officers, 3,794 enlisted men in four infantry and two artillery regiments, two companies of mounted dragoons, and a small engineer corps. By late 1802, Jefferson had reduced the Army's size to a mere 3,040 officers and men in two infantry regiments and one artillery regiment, and an engineer contingent made up of seven officers and ten cadets. Almost a third of the Army's officers had been dismissed! By diminishing its size so drastically, Jefferson intended to prevent a standing army from becoming an instrument of any political party, as the Federalists had attempted to make it. However, under the Republican Party, it was uncertain whether it would be retained as any kind of instrument at all.

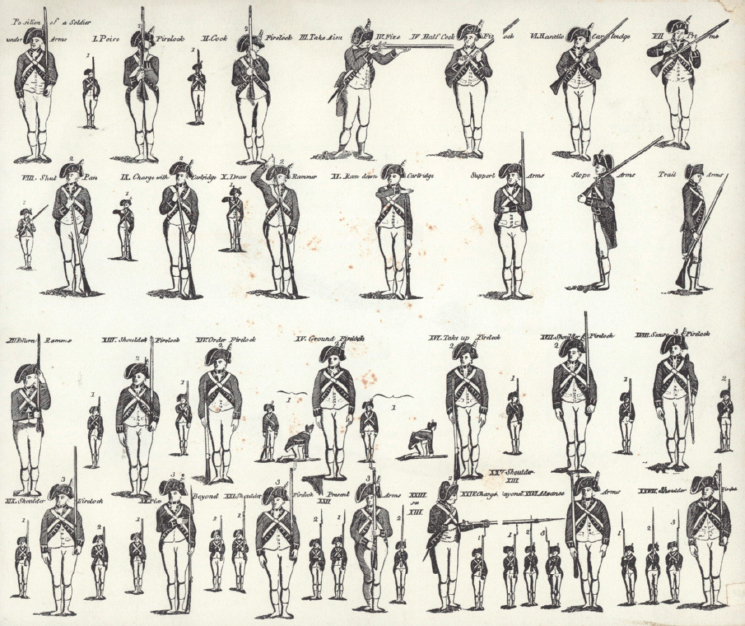

American Manual of Arms of 1802 showing drill exercises for the US Army.

The years of Jefferson's administration saw the army little used except for several exploration expeditions and road building projects. Although he objected to a permanent military establishment, Jefferson wanted its officers to be both educated and useful to American society in fields other than just the military art. To that end, he asked Congress to establish in March 1802 the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, an institution which would serve as the country's first engineering school, and provide the army with intellectual direction and doctrine.

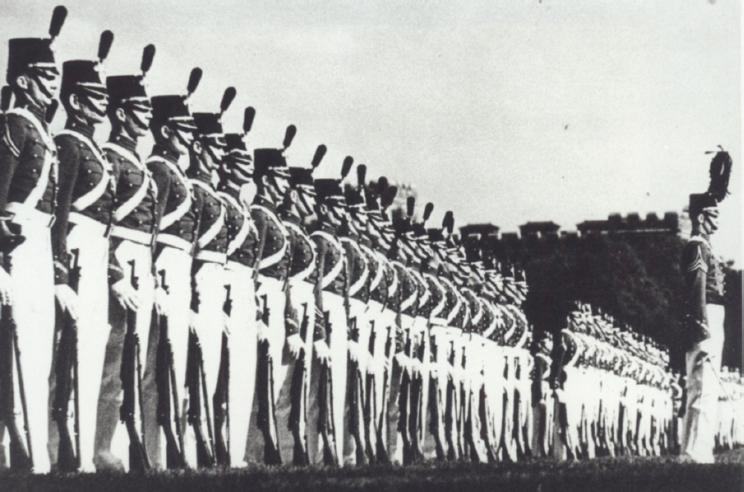

West Point Officer Cadets on parade in early 19th century-style uniforms. Although Jefferson severely reduced the size of the US Army, he did oversee the establishment of the US Military Academy at West Point in 1802.

West Point aside, the Commander-in-Chief was an indifferent administrator for whom the army stood on the margins of his concerns. The result was that pay was low, medical supplies, rations and clothes ran short, resulting in abysmal morale among the officers and men. When the Leopard-Chesapeakeincident occurred in 1807, the army's strength was below 2,400 men. The national uproar over the Chesapeake Affair stirred such anti-British feelings that Jefferson reluctantly secured authorization from Congress in 1808 to raise five new regular regiments of infantry and one each of artillery, riflemen and light dragoons. The aim was to have a force of 10,000 men under arms, but recruitment was so torpid that by 1812 the Army could only muster 6,744 souls.

Compounding the problem of a government that consistently deprived the armed forces of funds and manpower, the United States Army was poorly served by careless leadership. Jefferson's Secretary of War was Henry Dearborn, who eagerly joined with Jefferson in slashing military expenditures during his tenure. Paradoxically, he toyed with certain innovations in the Army, including promoting the use of the Model 1803 Harper's Ferry Rifle and the first US horse artillery. A passionate Republican politician, Dearborn was too close to the administration to shield the army from the cost cutting and indifference that hobbled it so badly under Jefferson.

If Dearborn was so thrift driven, he was at least moderately capable, something that cannot be said of his replacement. When James Madison came to the Presidency in 1809, he named Dr. William Eustis as his Secretary of War. The Cambridge, Massachusetts-born Eustis was a physician who had served during the American Revolutionary War as a volunteer surgeon. He lacked meaningful military experience, and like Dearborn before him pursued frugality to extremes. Some of these measures included doing away with the fledging mobile horse artillery company, and his refusal to authorize for cost-cutting reasons the purchase of fruits and vegetables for sick soldiers. He did, however, advocate increasing the size of the army, and the creation of a superintendent of ordnance, a commissary general, and a quartermaster general's department to better supply and move the army. Unfortunately, these sensible reforms, passed by Congress in early 1812, were not in place when hostilities commenced that June. Eustis and his 11 clerks in the department were overwhelmed by their many responsibilities, and his lack of managerial skill only compounded his organization's inability to cope with them. Describing the Secretary's failings, a Pennsylvania Congressman concluded Eustis was “a dead weight in our hands…. His unfitness is apparent to everybody but himself.”

US soldiers in 1813. Left to right: Drummer, US Infantry, wearing British coatee, part of consignment captured by American privateer; Private, US 16th Infantry; Field Officer, 28th US Infantry; (kneeling) Private, 6th US Infantry, wearing summer uniform and the regiment's distinctive bucktail in cap; Private, 17th Infantry, lacking his black coatee. Painting by Ed Dovey.

US soldiers in 1814. Left to right: Fifer, US Infantry, again wearing captured British coatee; Sergeant, 18th Infantry, winter dress including woollen trousers; Lieutenant, 18th Infantry; (seated) Private, 25th Infantry, in famous gray coatee, his haversack painted blue as waterproofing; Private, 7th Infantry. Painting by Ed Dovey.

The process of appointing field grade officers—generals and colonels—was an unmitigated disaster. Madison had to choose between naming Revolutionary War veterans in their 50s and 60s, none of whom had ever reached beyond the rank of colonel, or un-trained and untried politicians who had to be unabashed Republicans. The former, according to General Winfield Scott, “had generally, sunk into either sloth, ignorance, or habits of intemperate drinking.” Scott went further by describing many of his fellow officers as “swaggers, dependents, decayed gentlemen and others fit for nothing else … totally unfit for any military purpose whatever.” The political generals chosen by the President were in many instances recommended by Republican Congressmen, who unfortunately, “pressed upon the Executive their own particular friends and dependents.” The result was that few of the new officers had any experience of war. One senior general in the United States Army at the start of the conflict was James Wilkinson, financial swindler, confidence man, and traitor to his country, who had the distinction of never having won a battle or lost a court martial. The added irony was that he represented the very officer type the Jeffersonian political establishment so dreaded.

The officers, bad or good, at the start of the war led enlisted men for the most part who were inexperienced in war. Enlistments were for five years, and pay—for privates $5, non-commissioned officers $9, officers up to $20 per month, usually months in arrears assured that the pool of recruits was always slim. Short-term volunteers were raised but never in sufficient numbers. Only six such regiments were created and the general opinion of their army comrades was that the volunteers were little better than organized bandits who freely engaged in desertion and robbery.

Jefferson's cherished plan to use the militia as the nation's initial and principal defense force never came to fruition. Under the Militia Act of 1792, every free white male between the ages of 18 to 45 was eligible to be in the militia. While each member supplied his own weapon and equipment, the states were to organize them in military formations. Under the law, militiamen were obligated to serve the federal government only three months in any one year. In 1804, all but three states reported that they could raise a total of 525,000 militiamen in time of war. New England and the Western Territories were best prepared. The Carolinas could arm half their men, but the other states were lucky if they could supply weapons to one-fifth of their militia. Several states had laws forbidding their militia contingents from leaving the state. Worse, militia officers were state political appointees who put their political expediency above military concerns.

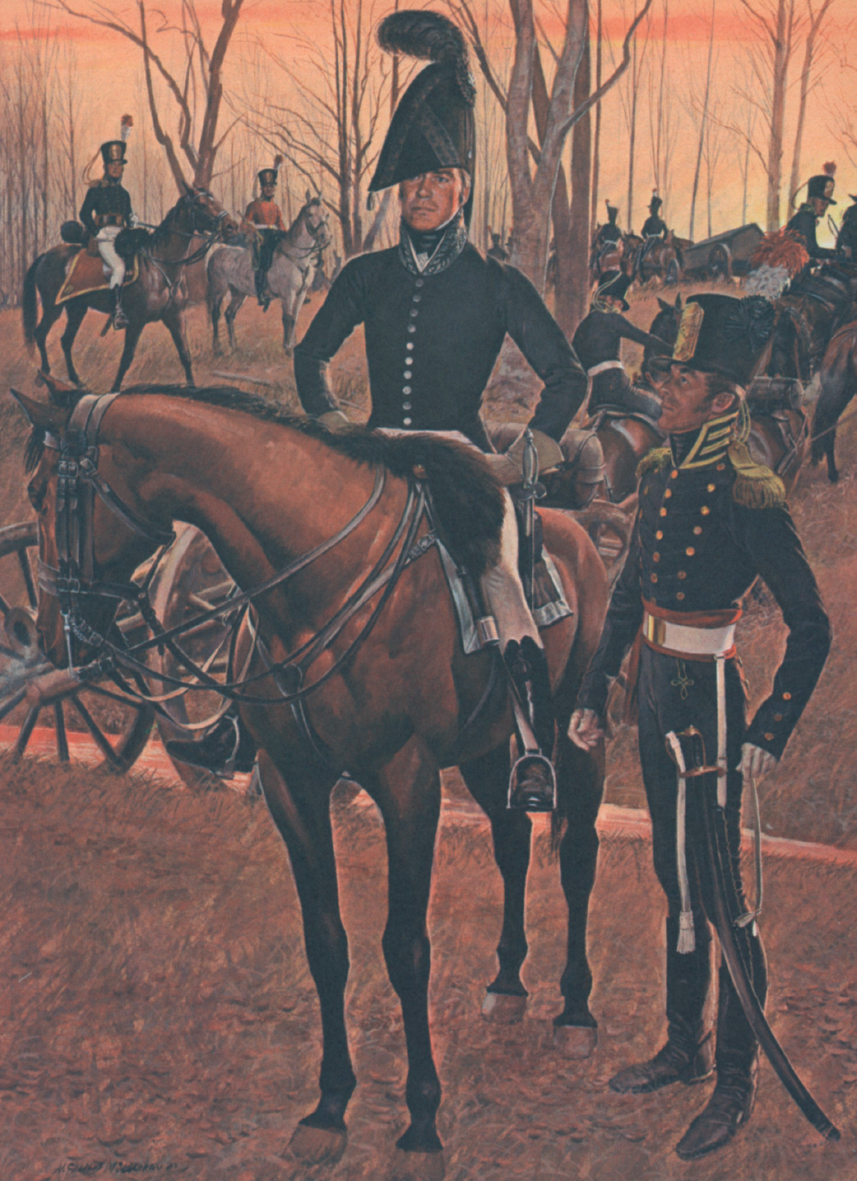

US Medical Corps Officer (left) and Light Artillery Sergeant on campaign in 1812. Painting by H. Charles McBarron.

In April 1812, with war coming ever closer, Congress requested the states to field 80,000 militiamen for federal service. The governors of New England refused! Their excuse was that their state's territory was not in danger of foreign invasion and therefore there was no legal reason their militia should be mobilized. Beyond this indifference to serving their country, militias were costly and ill-trained. In writing to President Madison on September 30, 1812, Henry Dearborn, now appointed a general, stated that “The expenses of the Militia are enormous, and they are of little comparative use, except at the commencement of war, and for special emergencies. The sooner we can dispense with their services, the better.” During the war, a staggering 450,000 militiamen were at one time or another mustered into United States service, but due to refusal to cross state lines, poor leadership and equipment, only half of this vast number ever saw combat.

Supplying the army was carried out by civilian contractors who were more interested in making a profit than properly filling the needs of the military. The result was that troops went without the basics such as clothes, shoes and other vital equipment for months at a time, and the food they got was usually of poor quality and scant quantity.

In the medical field, doctors attached to the army were few, and in an era of primitive med ical science most did not have the skills to combat disease or treat battle wounds properly. Epidemic diseases such as dysentery, typhoid fever, pneumonia, as well as infections, proved fatal to many soldiers during the war. Medicines were always in short supply, and those who survived their wounds or bouts of disease usually did so in spite of their treatment.

The Army had better luck when it came to its small arms, ammunition and cannon. A department to oversee ordnance was in place by 1812 and ran smoothly during the war. With established federal armories at Springfield, Massachusetts and Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and with additional factories built after 1812, the manufacture and repair of muskets and rifles and production of ammunition was unimpeded. Cannon were purchased from private foundries, such as the one operated in Connecticut by Eli Whitney.

In contrast to the Army, the US Navy entered the War of 1812 with a surprisingly high degree of professionalism and technological superiority. The country's youngest military service was authorized by an Act of Congress in March 1794, in response to attacks on American merchant vessels by North African pirates during the Barbary Wars. It had expanded between 1798 and 1805, but no new frigates had been launched since 1800. Saddled with the parsimonious and pacifist Jefferson administration, the blue water navy had to fight for every dollar of appropriations from a government which spent much of its limited budget on gunboats for harbor defense, not on an ocean-going fighting force. As a result, American naval strength was small, and hampered by a lack of navy yards that could adequately maintain the ships. Consequently, expectations for the effectiveness, and even the survivability of the tiny United States Navy were extremely low at the start of the War of 1812, but they would prove their doubters wrong.

In January 1812, the US Navy had only 14 commissioned warships: three 44-gun frigates, three smaller armed frigates sporting 28 to 38 guns, two 18-gun sloops, six brigs with 12 to 16 cannon each, with two more refitted frigates mounting 38 guns added to that number during the year. Opposing these were over 500 active duty combat vessels of the British Royal Navy. But unlike the Army, the American Navy was stiffened by about 500 career officers, many of whom had seen combat against the French in the Quasi-War of 1798–1800 and the Barbary Pirates of North Africa. Most were young men in their 30s and 40s, like David Porter Jr. and John Rogers, whose bombast and egotism reflected their high level of confidence and fighting spirit. Others such as William Bainbridge, “had all of [Stephen] Decatur's pride and vanity and touchy sense of honor with none of his dash,” were nonetheless formidable naval fighters. Stephen Decatur was the hero of the Barbary Wars with a string of naval victories to his name.

With all this combat service, there was no dearth of skilled and experienced sailors. The Navy listed 5,230 on its rolls, 2,346 of them fighting crews, the rest stationed in dockyards, coast defenses, and the Great Lakes. The term of service was for one year and pay ranged from $6 to $18 a month depending on job skills. As part of the Navy, a 1,000-man Marine Corps was authorized, but it never reached a strength of more than 500 during the war. Its members served as port and ship security and as naval landing parties.

Despite the severe size differential between the US and British navies, the Americans had some distinct advantages that counted strongly in combat. American ship crews were larger than their British counterparts, and American frigate design made for faster craft with greater maneuverability to buttress the considerable punch of their superior 24–pounder guns.

Despite the anticipation of war with Britain, Congress and the President made no effort to expand their fleet, even though the Navy Department warned that it would require 12 ships-of-the-line, each carrying 74 cannon, and 20 frigates to adequately safeguard the American coastline. Initial victories in 1812 spurred the administration to initiate a new naval building program intended to construct six 44-gun frigates and four 74-gun shipsof-the-line, but none of these were either completed or saw service during the war.

Besides the operations of the Navy, the United States resorted to privateering with great success. Most privateers were merchant traders, the largest contingent coming from Massachusetts, with some 150 vessels acting under letters of marque; that is, commissions to commit hostile acts against enemy shipping. Their reward for this blend of patriotism and profit was the money they made from the capture of enemy goods and ships. About 526 ships of all types and sizes, usually armed with one or two long guns, and able to race across coastal waters, were loosed upon British shipping. The best ship model used for this venture was the two-masted Baltimore clipper schooner. America's privateers, raiding the seas of North and South America and Europe, proved to be the most effective weapons aimed at British trade during the war.

USS Constellation clashes with FrenchL'Insurgente in February 1799 during the Quasi War of 1798–1800. Such undeclared warfare against the French Republic meant that American seamen were far more combat experienced than their army compatriots. Painting by John W. Schmidt.

“For this government,” wrote Lord Liverpool, Britain's Prime minister in June 1812, “the American War, in truth, is little more than an annoying distraction, albeit at a time we can ill afford it.” Engaged in a fight for its very existence against Revolutionary France and the Emperor Napoleon, British national attention had been exclusively focused on that struggle since 1793, while maintaining its economic influence around the world.

Of primary concern in North America were its several colonies north of the United States border: Lower Canada (modern Quebec); upper Canada (present day Ontario); Nova Scotia; New Brunswick; Newfoundland; prince Edward Island; and Cape Breton Island. Making up today's nation of Canada, these British colonies by the early 19th century had developed a thriving economy based on the fur trade, fisheries, wheat farming and lumber. The last was of vital interest to Britain, since as European-sourced ship building timber and masts became restricted, Canadian sources of this raw material made up the shortfall. Here was a vast supply of wood needed by the Royal Navy and the world's largest merchant fleet to keep it afloat; the defense of this important strategic supply was perhaps the most powerful motivating factor for keeping Canadian colonies in British hands.

The question for the United Kingdom in 1812 was how best to preserve these holdings against the young Republic to the south. In October 22, 1811, official instructions to Sir George Prevost, Governor-in-Chief and supreme military commander in British North America, were very specific. In case of war with the United States, British forces in Canada were not to commence offense operations, “except for the purpose of preventing or repelling Hostilities or unavoidable Emergencies.” Thus, the initial British strategy for the protection of Canada from American attack was set. It was a realistic decision based on the fact that the war against Napoleon was straining British imperial resources to the limit.

With the population of the USA at seven and a half million, versus only about 500,000 British subjects living in Canada, the manpower odds against the latter were crushing. Only about 7,000 troops were stationed in the area in 1812, a vast region stretching 1,300 miles from the Atlantic Ocean to Lake Michigan. Nor could additional soldiers be easily found. The bulk of the British Army under the Duke of Wellington was tied up in the Iberian Peninsula fighting the French. Since January 1812, he had been successfully driving the enemy from large parts of Spain. To take troops away from him at this critical juncture would have weakened his momentum and given the French an opportunity to recover. Furthermore, the transfer of men and material from Spain to Canada—a distance of over 3,000 watery miles—would have taken months, by which time Canada might have already fallen to the Americans.

Stephen Decatur boards a Barbary Pirate gunboat in 1804. Decatur's heroic victories were an inspiration to American naval commanders in the War of 1812. Painting by Dennis M Carter.

Another salient reason for the British to remain on the defensive was the attitude of many of its inhabitants—the fiercely independent French-speaking Canadians, and the Americans residing in the provinces. Some of the 80,000 residents of Upper Canada were Loyalist refugees from the American Revolution who had no sympathy for the United States, but there were many more westward moving Americans who either had little interest in the coming conflict or were actively pro-American. Lower Canada contained the largest centers of population, such as Montreal and Quebec. The settlers of this region were overwhelmingly French, and their loyalty as the conflict approached was uncertain. Overall, Canadian demographics demanded a defensive stance, at least at the war's beginning.

On the high seas, the British plan was to sweep American war vessels from the ocean, but the European war kept much of the Royal Navy confined to a role of blockading French ports, greatly reducing the number of British ships available to tackle the American Navy and its privateers. Control of the Great Lakes was another objective of the Royal Navy. Denying their use to the enemy would be a key part of its overall defensive strategy, which would greatly impede any American incursion into Canada, and then, when an offensive was finally assumed, serve as a watery highway into American territory. Along the US coast, British naval strategy, hand-in-hand with its objective of destroying American commerce, envisioned creating a “wooden wall” of ships in order to blockade enemy warships and privateers in port. In the process, it hoped to strangle American seaborne trade by preventing cargo from entering or leaving the United States.

“There, it all depends upon that article whether we do the business or not.” Thus declared the Duke of Wellington on the eve of the battle of Waterloo—“that article” being the British regular infantryman. At the start of 1812, there were only 5,600 British regulars serving in Canada. These troops would remain the backbone of the defense of British North America for the entire war. They would give outstanding service during the conflict due to their training, esprit, and familiarity with the country and peoples of the area. While a small reinforcement of regulars trickled into the theater in 1813, it would not be until the close of the European war against France that tens of thousands more British soldiers, mostly from Wellington's army, were sent to North America.

Among the British regular units found in Canada at the start of hostilities were the 8th (King's) Regiment, the 41st, 49th (both having been in Canada for a decade and a half), the 98th, 99th, 100th Regiments of Foot, the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion, and 450 gunners of the Royal Artillery Regiment. Also counted in the ranks as regulars were the 104th Regiment of Foot (New Brunswick Fencibles), the Royal Newfoundland Regiment of Fencible Infantry, the Canadian Fencibles, and the Nova Scotia Fencibles. These Fencible formations were Canadian-raised colonial regular units within the British Army establishment, trained on the British model, and led by British officers. Another fine fighting force raised in Canada, this one from among Scottish settlers, was the Glengarry Light Infantry Regiment, which saw much action in Upper Canada during the war.

Lower Canada raised 6,500 men for military duty in early 1812. Their members were in the majority French Canadians who, as one British officer put it, “perhaps did not love the English Government or people, but they loved the Americans less.” The Canadian Voltigeurs was one of the area's units mustered in and was listed as one of the British regular forces on the Army Returns.

Regular soldiers in British service were traditionally recruited from the laboring class. Pay ranged from one shilling a day for a private, to a shilling and 2-1/4 pennies for an infantry corporal, and a shilling and 6-3/4 pennies for a sergeant. Deductions for lodgings while on the march and other “necessaries” soon reduced the soldier's wages to a pittance. What made them so formidable in combat, especially compared to their American counterparts, was the intensity of their training, iron discipline, and being well equipped and led.

The line officers commanding British soldiers were recruited from the privileged class and could obtain higher rank, at an official rate of purchase, up to the grade of Lieutenant- Colonel. Most British officers, from ensigns to army generals, were not professionally trained in the arts of war, but coming from a sporting class, they instinctively provided the inspiration and leadership required to command men in battle. Furthermore, war, like sporting events, included competition, and success in war meant promotion, honor and glory. Those officers who served in colonial stations, like Canada, were usually not financially able to buy their way into a prestigious regiment serving in England or Spain. As a result, many of these men were keen on making the Army their vocation and excelling at it. The result was a high proportion of good combat leaders facing the Americans in the War of 1812.

Fortunately for Great Britain, the senior officers in command of the army in Canada at the start of the War of 1812 were up to the task of defending their charge. They were professional soldiers capable of organizing, training and leading troops in battle, as well as competent to deal with the problems of civil administration. They ranged from the cautious Brigadier-General Sir George Prevost to the extremely audacious Major-General Isaac Brock, the prudent Major-General Roger Sheaffe, the detached Major-General Baron Francis de Rottenburg, and the persistent Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond. They also had the singular advantage of facing American generals in 1812 who were poor military leaders due to inexperience, and in some cases pure incompetence.

Besides the British Army Regulars and trained colonial units, Canada possessed a considerable militia force, at least on paper: 11,000 men from Upper Canada; 54,000 from Lower Canada—termed Lower Canadian Sedentary Militia; 12,000 from Nova Scotia; the New Brunswick militia 4,500 men strong; and small contingents from the other Atlantic provinces of Newfoundland, Prince Edward and the Cape Breton Islands. According to General Prevost, the militia, especially from Lower Canada, was “a mere posse, ill armed and without discipline.” Regardless of Prevost's opinion, these French-Canadians were a sturdy lot, good hunters, excellent marksmen, and adept at Indian-style skirmishing in the vast Canadian forests. At the commencement of the war, most of the militia did not possess uniforms but wore homespun clothes. Five battalions of Lower Canadian militia were raised in 1812 and did good service during the conflict. The Upper Canadian militia provided eight battalions of 4,000 men prior to the war, a number largely filled by revenge-seeking Loyalist refugees from the United States.

Like that of the United States, Canadian militia forces were present in virtually every major engagement of the war. Besides their combat role, they served as garrison troops as well as providing labor for the construction and repair of fortifications. While surprised at the reliability of the militia during the war, British authorities still had to contend with their high desertion rate, a problem never satisfactorily solved during the conflict.

One other force available to help the British fight for Canada was the Indians. After their defeat by William Henry Harrison at the battle of Tippecanoe, on November 6, 1811, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh led his people to join the British at Amherstburg, also known as Fort Malden, on the northwest shore of Lake Erie. There, he and his people came under the authority of the Indian Department, which was charged with carrying on diplomatic and military relations with all Indian tribes in British North America. Its staff of 100 lieutenants, captains and interpreters was responsible for securing military cooperation between the Indians in Upper and Lower Canada and the military by providing instructors and support for the Native American contingents fighting with the British. Tecumseh's 600 warriors were a welcome addition to the British defense of Upper Canada in 1812, and proved their worth before the year was out.

Lord Liverpool, British Prime Minister during the War of 1812. Based on portrait by Thomas Lawrence.

Of vital aid to any defense of Canada was the Royal Navy. But when America declared war on Britain, its naval power was fully committed to the struggle against Napoleon. In September 1812, three months after America and Britain went to war, the Royal Navy had no more than 79 warships in the western hemisphere. These included 11 ships-of-the-line, 34 frigates, and about the same number of smaller schooners, sloops and brigs. Moreover, this paltry force was spread thinly, escorting merchant shipping, protecting the Saint Lawrence River, chasing American war vessels, and hunting enemy privateers. Thus, the British Admiralty could not effectively in the first six months of the war blockade the America coastline in order to render United States naval forces impotent, or cut American trade.

The Royal Navy had 1,000 warships in its arsenal with over 550 operational at any one time. Consuming a quarter of Britain's annual budget, the Navy was the most professional and well-trained maritime force in the world. In 1812, its fleets were manned by over 113,600 sailors, but the insatiable need for more seamen never abated. Yet the largest navy in the world did have its weaknesses.

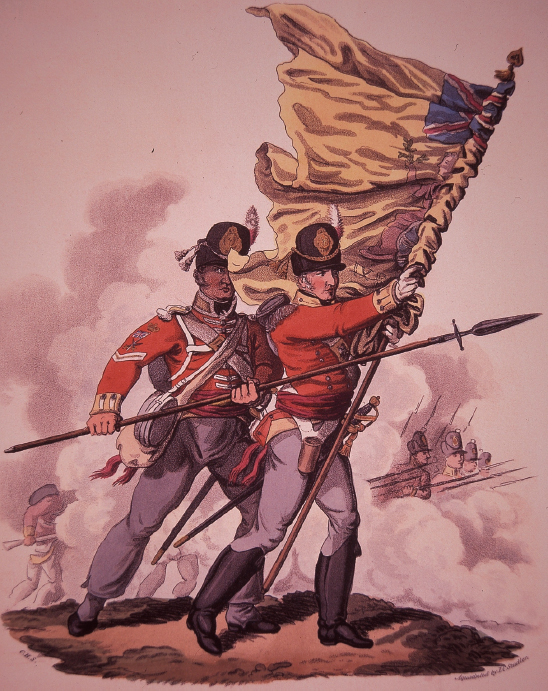

British Army Ensign and Colour Sergeant. Print published in 1813.

Desertion from ships by their crew was endemic, and no amount of impressment or flogging ever solved the problem. The result was that even with higher wages being paid to common seamen after the naval mutinies of the 1790s, the Navy had to habitually man its fleets with smaller than required complements.

After its victory at the battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the Royal Navy concentrated on economic warfare against France by blockading the French coast. Such a task required a large number of vessels, and after 1805 these were mass-produced, based on a smaller ship design, with less armament and crew than the newer and technically more advanced American frigates. The result was an imbalance in combat capability when, early in the war, one-on-one battles occurred between American and British warships.

If British ship designs were not the best to fight the Americans in 1812, and the dearth of crewmen was an impediment to the proper performance of a ship, there was little to complain about when it came to officers of the Royal Navy. They came from all classes of British society: the aristocracy, the professions, business and commerce, navy families and merchant traders. There was no purchase of rank in the navy—six years at sea and passing a seamanship examination was the qualification demanded before receiving an officer's commission. Merit and practical experience was the key to the Royal Navy's leadership excellence and dominance of the world's oceans.

In tandem with the activities of the blue water navy, British occupation of the Great Lakes was vital to the defense of Canada in 1812. Under the command of the Provincial Marine, the small colonial-operated squadrons that plied Lake Ontario, Lake Erie and Huron were instrumental in interdicting American troop and supply movements across those waterways. It was a portent of things to come—to invade or defend Canada, the Lakes had to be secured.

On July 12, 1812, an American military force crossed the Detroit River, north of Lake Erie, and entered upon Canadian soil. Taking control of the village of Sandwich, this incursion was the opening shot in the War of 1812—a war for which America was unprepared and wanted a quick conclusion, and one in which the British were very uncertain of success. Canada was now in abeyance, and only time would tell if its defense forces could fend off the attackers.