“THE OFFICERS OF THE [PROVINCIAL] MARINE APPEAR TO BE DESTITUTE OF ALL energy and spirit,” was the evaluation of a report to Sir George Prevost regarding the action fought on November 10, 1812, at Kingston harbor between US and British naval forces on Lake Ontario. That engagement, in which each side suffered only one killed and a few wounded, secured American control of the lake for the remainder of the navigation season. The American attack, led by Commodore Isaac Chauncey, on Kingston, located at the point where the St. Lawrence River enters Lake Ontario, was long overdue, since the war had been in progress for ten weeks and control of the Great Lakes was vital for US operations against the Canadian border.

The Connecticut-born sailor, born on February 20, 1772, joined the US Navy in 1798 and participated in the Quasi-War as a 1st Lieutenant. His service in the war against the Barbary pirates earned him a captain's rank, and he was later head of the New York Navy Yard. In September 1812, based on his proven administrative ability, he was given command of US naval forces on Lakes Erie and Ontario. He transformed the village of Sackets Harbor (spelled Sackett's at the time) into America's main naval base on the Great Lakes, complete with shipbuilding and maintenance facilities. By late fall, he had supplemented the brig Oneida, sporting 18 32-pound short-range carronades, with four more armed schooners.

During the War of 1812, control of the Great Lakes rested with the side with the largest, most heavily armed ships. When Chauncey seized the initiative early in November, his target was the Canadian Provincial Marine's most powerful vessel, the corvette HMS Royal George, armed with 20 32-pounder carronades. Neutralizing her would give America dominance over Lake Ontario, thus cutting Upper Canada off from men and material, which could only flow to it along the St. Lawrence River via Montreal.

On November 10, Chauncey sailed from Sackets Harbor with the Oneida and six schooners, armed with a total of 63 cannon, seeking the six British ships opposing them on the lake, carrying a total of 106 guns. After destroying an enemy schooner, the US flotilla sighted Royal George and followed her into Kingston harbor. For two hours they exchanged long-range fire, with little damage inflicted on either side, before the Americans broke off the action. Although tactically inconclusive, the battle closed Kingston's port to British shipping, forcing the Provincial Marine's units to disperse to other havens. On November 26, Chauncey's advantage over the British increased with the launching of the corvette USS Madison, armed with 24 32-pounder carronades, built at Sackets Harbor in only 45 days.

Captain James Lucas Yeo of the Royal Navy was given command of British operations on the inland waters in North America in 1813.

The American success at Kingston prompted the British Admiralty to take over conduct of naval operations on the inland waters, as-signing Captain James Lucas Yeo of the Royal Navy to the job. The 30-year-old veteran, born October 7, 1782, joined the navy as a lieutenant in 1797, and made captain in 1807. His varied accomplishments included command of warships and amphibious expeditions, until his appointment on March 19, 1813 to North America. Yeo opened shipyards at Kingston and York.

At this time, Marylander Jessie Duncan Elliott, a lieuten ant in the US Navy, was tasked with establishing a naval station at Black Rock, on the Niagara River just north of Buffalo, New York. Further west on Lake Erie's south shore, 80 miles west of Black Rock, Presque Isle was being made ready as a naval base in lieu of Fort Erie, which was still in British hands.

To command the American naval presence on Lake Erie under Chauncey, Rhode Island native Oliver Hazard Perry was picked in February 1813. At the age of 17 he had been made a navy lieutenant; only five years later, he was building gunboats for the US government. Ordered to Presque Isle to construct two brigs, Perry arrived at that barren site on March 13, 1813. He remained seriously short of men and material, and the US positions at Presque Isle and Black Rock were easy prey for the forces of Lieutenant Robert Heriot Barclay.

The Scottish Barclay joined the Royal Navy in 1787 and served as acting lieutenant at the battle of Trafalgar. He lost his left arm in 1809 fighting the French. Transferring to the North American station, he was made naval commander on Lake Erie. Barclay was dissatisfied with the personnel manning his ships, composed of disgruntled Provincial Marine members and soldiers. He detested the staff Yeo had assigned him, who Barclay claimed were “the most worthless Characters that came from England.” More concerned over the strength and effectiveness of his Lake Ontario squadron, Yeo did little to adequately reinforce Barclay's weak naval contingent.

“Montreal is the principal commercial city in the Canadas,” wrote George Prevost to the British Prime Minister on May 18, 1812, “and in the event of War, would become the first object of attack.” He went on to affirm that “Quebec is the only permanent Fortress in the Canadas —it is the key to the whole and must be maintained.” Thus, did the man responsible for safeguarding British North America succinctly indicate the two cornerstones upon which the defense of Canada rested during the War of 1812.

At 44 years old, Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost assumed his position as civil and military head of Canada in September 1811. Joining the British Army in 1779, he was a Brigadier-General by 1798. Prevost commanded troops in the West Indies, including Dominica, which he successfully defended against the French in 1805. In addition to his military record, he performed well as a civil administrator of St. Lucia, Dominica and Nova Scotia. In 1811, he was made Lieutenant-General. With a background of military and political achievement, Prevost seemed the perfect choice to govern the Canadian colonies. Modern historians are divided over Prevost's generalship, some calling it timid and indecisive, others stating he was merely defense-minded. Whatever it was, Prevost continued the struggle with the United States in 1813 by following a defensive policy.

At the age of 22, Rhode Island native Oliver Hazard Perry was ordered to command the American naval presence on Lake Erie in February 1813.

While Sir George clung to a passive strategy, the new US Secretary of War, John Armstrong, planned to take offensive action in the east. Armstrong's scheme, as amended by Dearborn and Chauncey, provided for the movement of 1,700 troops from Sackets Harbor, escorted by the fleet, to attack York. Then, in conjunction with 3,000 men from Buffalo, Forts George and Erie on the Niagara River would be taken. Finally, the combined force would move on to Kingston, thus blocking the main supply artery along the St. Lawrence River from Lower to Upper Canada. York was made the initial target because the capture of the enemy ships reported there, in addition to its naval facilities, would give control of Lake Ontario to the Americans.

York—now modern Toronto and capital of Upper Canada—was the home of 500 souls. Its defenses consisted of a two-story blockhouse surrounded by a wooden stockade at its eastern end. To the west, more than a mile from the blockhouse and fronting the lakeshore, was situated one battery at the mouth of Garrison Creek, a second next to the Lieutenant Governor's house, a third, named the Half-Moon Battery, 400 yards from the Governor's residence, and the Western Battery 300 yards farther on. The town's ammunition was stored in Fort York, a little to the west of the Governor's mansion. The York garrison at the time of the American attack was 300 regulars, 350 militia and 50 Indians.

Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, civil and military head of Upper Canada, was at York at the time of the American attack. A brave but cautious general, his leadership style did not inspire his subordinates or superiors. Chauncey's squadron of 14 ships, mounting 83 cannon and carrying 1,700 US regulars and volunteers, sailed from Sackets Harbor on April 25, 1813. Brigadier-General Zebulon Montgomery Pike—a promising military commander—laid out the plan for the assault on York. He explained that Major Benjamin Forsyth's Rifle Regiment would be the first to land on the beach, and then act as a protective screen for the first wave of infantry coming ashore. After the entire amphibious corps landed, it would form column, covered on the flanks by the riflemen, and march east against the enemy artillery positions. Pike issued orders that all civilian property must be respected and that any soldier “guilty of plundering, if convicted, be punished with death.” Pike, not Dearborn—who was ill—led the mission.

At 7:00am, April 27, men of the US Rifle Regiment took to small boats for the run to shore—no more than 300 men could be moved to the landing area at a time. The American plan was to land in clear fields just west of Fort York, but strong winds pushed the boats two miles further west to a wooded coast, which afforded the defenders cover. As the Americans landed, Sheaffe ordered his Indians and the grenadier company from the 8th Regiment of Foot to meet the invaders on the shoreline. First off the boats was Forsyth, who bellowed, “Men follow me.” Lining up his men, he had them fire a volley that decimated the advancing British. The Rifle Regiment then engaged in bitter tree-to-tree firefights until the Indians fled, but the British regulars held their position. Ensign Joseph Hawley Dwight, 13th US Infantry Regiment, recalled that, “The enemy met us at the water's edge and fought us like men. The militia ran away almost at first fire. The regular [British] troops stood their ground until almost all were killed or wounded.”

American and British sailors clash in fierce close quarter fighting.

The US 15th Infantry Regiment landed after the riflemen, with bayonets fixed, under a hail of fire. Pike soon came ashore to assume personal command. His aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Donald Fraser, recalled that as he did, “the balls whistled gloriously” over our heads. As the British grenadiers were pushed back by Forsyth's sharpshooters, Sheaffe arrived with the rest of the 8th Foot, the Newfoundland Fencibles, and a few dozen militia. After falling back before the accurate American shooting, Sheaffe tried but failed to get the Fencibles to renew their advance. As losses mounted, the main body of the British retreated east with the newly arrived Glengarry Light Infantry Regiment covering their withdrawal.

Meanwhile, the American warships duelled with the four British gun batteries, and according to seaman Ned Myers of the USS Scourge, the ships were having some “sharp work with the batteries, keeping up a steady fire.” At 10:00am, Pike's column moved east along the lake road through a forest. No provision had been made by the British to block the narrow trail the Americans were moving along; instead. the Redcoats remained near the batteries while the Canadian militia milled around Garrison Creek.

By 1:00pm, the Americans had reached Fort York. US artillery commenced to fire at the fortification, while the fleet continued to engage the shore batteries. Suddenly, 300 brrels of gunpowder in the fort's magazine blew up after the retreating British rigged them for demolition, spreading debris over a 500-yard radius. The blast killed dozens of Americans and wounded over 200 others, among them General Pike, who had been observing the action from the Half-Moon Battery. He died later that day. One shocked witness recalled, “The noise of the explosion was tremendous. The earth shook and the sun was darkened. It seemed like heaven and earth were coming together.” Meanwhile, Sheaffe evacuated York and marched his men east to Kingston. Colonel Cromwell Pearce, 16th US Infantry Regiment, Pike's successor, failed to press the pursuit of Sheaffe, allowing him to escape.

On April 28, Dearborn accepted York's surrender, and although the one unfinished brig remaining there was destroyed by the British, 20 artillery pieces were captured by the Americans. Over the next two days, the town was sacked by the conquerors. The Parliament Building, Governor's mansion, and military buildings were torched, and many empty homes were robbed. There were no recorded murders or rapes. The fight for York cost the United States Army 60 killed and wounded, with another 38 killed and 222 wounded by the magazine explosion. British losses were 59 killed and 94 injured. The American expeditionary force re-embarked on May 1st and sailed for the mouth of the Niagara River, arriving there on the 8th.

Death of American Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike at the battle of York (now Toronto) on April 27, 1813. He was killed, alongside 250 US casualties, when the retreating British blew up their gunpowder stocks.

Following the loss of York, the moment seemed urgent for the British to attack the United States' most important naval asset on Lake Ontario—General Vincent's position on the Niagara was in jeopardy, the US squadron under Chauncey was not at Sackets Harbor to defend it, and the military force defending the place was weak. On May 27, Prevost and Yeo gathered from the Kingston area 800 regulars, 60 Fencibles, and a party of Indians— 900 men in total and two light cannon, all under Colonel Edward Baynes of the Glengarry Regiment. Eight warships and gunboats, mounting 82 guns and manned by 700 sailors, transported the troops.

The task force sailed from Kingston, only 36 miles from Sackets, and soon the men were ordered into the small boats that would take them ashore. However, rain and strong winds forced them back aboard their transports. Around noon on the 28th, two American schooners detected the approach of the British and sounded the alarm. The Americans spent the day calling in reinforcements to the town and putting them into defensive positions. Relying on the two gun batteries at Fort Tompkins and Fort Volunteer to deter the enemy from entering the harbor, the town's commander, Jacob Brown, placed 600 New York militia and one artillery piece southwest of the village along the water's edge behind an embankment. Behind them were 313 dismounted light dragoons and one gun. On Horse Island, connected to the mainland by a 300 yard causeway, was stationed the 167-strong Albany Volunteers with one gun. Total strength of the American garrison was 1,450 men.

As weak as the American forces were at Sackets Harbor, they were lucky to have a capable leader. Jacob Brown, a Quaker, was born in Pennsylvania on May 9, 1775. Intelligent and brave, Brown was one of the better American generals in the war and his performance at Sackets Harbor would earn him a commission as brigadier general in the US Regular Army.

At 4:30am on the morning of May 29, the British made for a cove a mile from town. From there they were to push up the lakeside wagon road above the cliffs and enter Sackets from the rear. As the British boats neared shore, Lieutenant David Wingfield of the Royal Navy recalled that enemy musket and artillery fire was unleashed on them and that “Almost every shot did execution, which for a moment staggered us.” But the British kept approaching, with their gunboats providing covering fire. Prevost brought up the rear of the landing party.

Before reaching the cove, strong winds diverted the landing force to the causeway that connected Horse Shoe Island to the mainland. After gaining the causeway, the British formed and charged across it, routing the American militia to their front. Witnessing the stampede, American Dragoon Lieutenant George Birch recalled that the “militia found the enemy pills too hard to digest and would not wait for a second dose but was making the best use of their legs and left the enemy to form and march against us.” Behind the militia, the Albany Volunteers loosed a few well-aimed volleys, then retreated back toward the dragoons.

One of the heroic American moments of the War of 1812 as Perry keeps fighting during the battle of Lake Erie by shifting his command—and his flag—to USS Niagara. Painting by William H. Powell.

The main body of the attackers started moving northeast along the lakeshore road toward Sackets while the 104th Foot, Canadian Voltigeurs, and Indians pursued the fleeing American militia. The main British column was met by the dragoons who fired disciplined volleys into the Redcoat ranks, but, being outnumbered, could not stop them. The Americans retreated to the town, taking station near a blockhouse and Fort Tompkins. Brown was somewhere to their rear trying to join them when he ran into British troops. He slipped away, spending the rest of the battle rallying his militia.

As the British column neared the west edge of Sackets Harbor, artillery fire from Fort Tompkins, just above the village, showered the troops with cannon balls, supplementing the American musketry already hitting them from the blockhouse sitting on a bluff. Prevost formed his men, not more than 300, and attacked the blockhouse and fort, even though the British ships off to their left were stilled by a lack of wind which prevented them from maneuvering into good firing positions in order to support their army comrades.

The next half hour saw a fierce firefight between the British and the dragoons, with some of the latter drawing away to the east, but a few obstinate American defenders remained to stall the enemy. In the town, Americans burned the stores and equipment at Navy Point shipyard. The British requested that the Americans surrender but the demand was rejected. Staggered by the loss in his command—over half his men were down—and the fleet unable to help, his field artillery not yet come up, and hearing that more American troops were pouring into Sackets from the east, Prevost ordered a withdrawal. The American officers at Fort Tompkins refused to give chase. By 7:30am, the Redcoats were returning to their waiting transports.

The dispirited British sailed for Kingston on May 29, having lost 46 killed and 179 wounded. In return, they captured one artillery piece and 150 prisoners. “The expedition,” confessed Prevost in a letter to his government, “has not been attended with the complete success which was expected from it.” Tactically a failure, the attack on Sackets Harbor did unnerve Commodore Chauncey enough that he was ever after reluctant to leave it unless it was strongly guarded by land and water. As a result, he based his future plans on protecting his base more than defeating the enemy.

Contemporary print version of Perry's heroic moment as he brings his flag to the Niagara, published in Philadelphia.

“It will not be amongst the least of General Proctor's mortifications,” wrote William Henry Harrison to the US Secretary of War, “to find that he has been baffled by a youth who has just passed his twenty-first year.” Harrison was reporting on the August 1–2 repulse of the British, under Henry Proctor at Fort Stephenson, located near Sandusky, Ohio by Major George Croghan, 17th US Infantry. This setback, and another failed effort at Fort Meigs in late July, along with dwindling numbers of regular troops and Indians, ended British offensive operations in the west. The next act in that theater would be the decisive battle for Lake Erie.

On July 29, 1813, Richard Barclay inexplicably withdrew his blockading force from Presque Isle, allowing Oliver Perry to bring his ships out of the port into Lake Erie between August 1st and 4th. Perry then conducted sweeps of the lake from a base at Put-in-Bay. Faced with a lack of food and pay, and knowing he would not be receiving any additional manpower for his ships, Barclay weighed anchor from Amherstburg on September 9, resolving to “sail and risk battle.” On Friday the 10th, the opposing squadrons came into contact. The British had three brigs and three schooners, with a total armament of 63 guns; the Americans had two brigs, two schooners, one sloop and four gunboats, mounting 54 cannon.

With USS Lawrence reduced to a wreck by the gunfire of two British ships, Perry was rowed half a mile away under enemy cannon fire to board the Niagara.

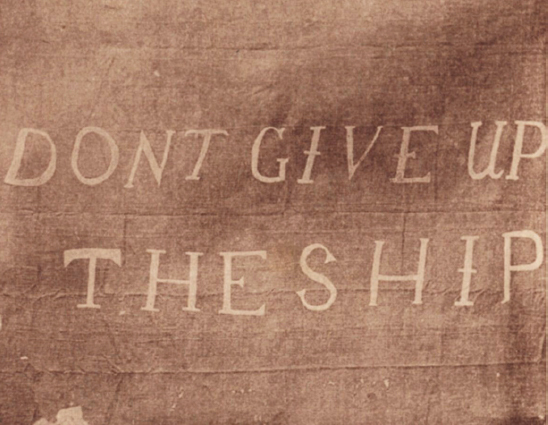

Remains of the flag that Perry first raised on USS Lawrence during the battle of Lake Erie, displaying the last words of James Lawrence of the USS Chesapeake “Don't give up the ship.”

Barclay hoped to use his longer-ranged weapons to stand off from his more numerous enemy, and pound them from a distance. That tactic could not be employed since the wind proved to be very light, giving the American force the wind advantage, which it used to rapidly close with the British. Perry admonished his captains to “engage your designated adversary, in close action, at half cable's length.” He intended to lay alongside the largest British vessels—the 11-gun Detroit and 17-gun Queen Charlotte—with his most powerful craft, the 20-gun Lawrence and 20-gun Niagara, while his other ships engaged enemy vessels of equal size. At 10:00am, Perry's ships cleared for action and he raised a dark blue flag displaying the last words of James Lawrence of the USS Chesapeake: “Don't give up the ship.”

Almost two hours later, Barclay opened fire at 2,000 yards. The two sides closed in line-ahead formation, except for the Niagara, which fell behind and did not join the fight until midday. For the next two and a half hours, the Lawrence was pummeled by the Detroit and Queen Charlotte, and reduced to a wreck with 83 of its 103-man crew killed or wounded, and her guns silenced. Perry left the Lawrence and rowed half a mile under enemy cannon fire to board the Niagara. Jessie Elliott, Niagara's skipper, left her to direct the gunboats, while Perry took charge of the ship. On the British side, Barclay, twice wounded, had to relinquish command, while five of six of his ship commanders had been either killed or disabled.

The pivotal moment in the battle occurred when Queen Charlotte passed astern of the badly damaged Detroit to engage Niagara with her starboard battery. The maneuver caused both British ships to become entangled, with Queen Charlotte's bowsprite ensnared in Detroit's mizzenmast. Unable to move or effectively return the American's fire, which was being delivered at only 100 yards with wood shattering carronades, the two British warships struck their colors at 3.00pm. Soon after, the rest of the British squadron was captured. In this Battle of Lake Erie, the Royal Navy suffered 41 killed, 94 wounded, and 306 captured, compared to an American loss of 27 killed and 96 wounded. With control of Lake Erie, the United States had effectively won the war in the west.

Perry takes the surrender of the British fleet at the battle of Lake Erie aboard the wrecked Lawrence. From painting by W.J. Aylward.