OPERATIONS IN THEOLDNORTHWEST CAME TO A HEAD IN LATE 1812. AMONG these were the Americans' autumn search-and-destroy missions against the Indians in Ohio and the Indiana and Illinois Territories. They were designed to counter the attacks by Tecumseh that threatened American settlements, as well as Major-General Henry Harrison's left flank as he advanced toward Detroit. To combat this growing menace, punitive expeditions were undertaken.

One such action was led by Lieutenant-Colonel John B. Campbell, 19th United States Infantry Regiment. In mid-December 1812, he set out with 600 cavalry and infantry to destroy the Miami Indian villages along the Mississiniwa River, a tributary of the Wabash, in Indian Territory. On the 18th, his encampment on the Mississiniwa was surprised by a pre-dawn assault by Miami and Pottawatamie braves. According to Private Nathan Vernon, a member of the Pennsylvania volunteer company known as the Pittsburg Blues, the Indian attack was unleashed “as if all the fiends of the lower region had been loosed upon us.”

Musket volleys ripped the darkness while the Indians probed for weak spots in the American lines, and the soldiers rushed to shore up any position where the enemy was “playing Hell.” At daylight, the Natives drew off and the American cavalry was ordered to pursue, but most did not. One trooper so instructed recorded that “the horse soldiers feared venturing into the Heathen filled timberland and did not obey the order.” Unhindered, the enemy made good his escape. US losses were eight killed and 48 wounded; the Indians 47 killed and 75 wounded. With ammunition and food almost gone, and many men suffering from the bitter cold, Campbell started back for Grenville, Ohio, his mission unaccomplished.

“As if all the fiends of the lower region had been loosed upon us”—bitter hand-to-hand fighting as US soldiers clash with Indians during search-and-destroy mission along the Mississiniwa River.

Following Harrison's order of late December 1812, James Winchester's column reached the Grand Rapids on the Maumee River on January 10, 1813. By then, Harrison's army had been reduced to 6,300 men. Winchester's own force had fallen by one half to 1,300, due to disease and severe winter weather. According to one of his men, William Atherton, Winchester's soldiers had “nothing but hunger and cold and nakedness staring us in the face.” Additionally, his officers and men, mostly Kentuckians, felt that the 60-year-old was militarily incompetent and resented that a Tennessean had been placed over them. Winchester was in fact born in Maryland, but relocated to Tennessee after the Revolutionary War. During that conflict he had been a regular army officer. When he moved out west, he became a general of Tennessee militia and an ardent Republican, factors that explain his appointment in March 1812 as a Brigadier-General in the US Army, and commander of the new Army of the Northwest after Hull was defeated at Detroit. Superseded by Harrison, Winchester supervised the army's left wing, at which point he proved to be a military leader of minimal talent.

Although isolated by 50 miles from the rest of Harrison's army, Winchester was not concerned as he ordered the construction of a poorly located camp on the Maumee River, near today's Perrysburg, Ohio. On the 14th, he dispatched 560 men to capture the hamlet of Frenchtown (modern Monroe, Michigan), 30 miles to the north, which housed 250 Canadian militia and Indians, and a single three-pounder cannon. Reaching his objective on the 18th, Frenchtown, situated on the north bank of the frozen Raisin River, was stormed by the Americans. After taking the village, they chased their enemy into a nearby wood where the pursuers suffered 12 killed and 55 wounded as the Canadians and Indians expertly fell back, firing as they went. After the fight, Winchester moved his entire command to Frenchtown. On January 21, he heard the British were at Brownstown, 18 miles away, preparing to move against him. He dismissed the report as baseless.

At Amherstburg on the 19th, the British Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Proctor addressed his officers, declaring, “My boys, the enemy is upon us and we are going to surprise them”—by attacking Frenchtown. This quick and decisive decision by the normally cautious, methodical professional was out of character, but the right one. Proctor's birthplace was Ireland in 1763. He went from Ensign to Lieutenant-Colonel between 1781 and 1800, mostly by purchase. He was assigned to Canada in 1802, and in mid-1812 was assigned the Western District of Upper Canada by his superior, Brock.

Proctor marched 334 regulars, 212 militia, 28 sailors, and 600 Potawatomi, Miami, and Wyandot Indians, with six small artillery pieces, to Brownstown on the 21st. At dawn the next day the British halted just outside Frenchtown, dressed their lines and positioned their cannons. Alerted by the commotion, the American defenders rushed to the picket fence that passed for a defensive palisade, and commenced shooting at the Redcoats. Caught in the open, the British were cut up badly, forcing them to pull back to a wood. John Richardson, a Canadian volunteer in the 41st Foot Regiment, upon seeing British wounded being killed by American sharpshooters, screamed to his fellow soldiers that “Those wretches are killing our poor defenseless boys.” The British artillery, which was intended to clear the Yankees from their position, had 13 of its 16 members mowed down because the guns had been moved too close to the Americans. One of the gunners yelled to his comrades, “Give them canister. They cannot suffer it at this distance.” As he loaded his cannon, he was shot dead.

As the British infantry absorbed the withering enemy fire, Proctor's Indian allies poured past both sides of the town and crossed Raisin River. Soon the American line, hit by musket fire from front, flank and rear, broke, as the Kentucky militiamen fled across the water. The Indians, according to one British eyewitness, “with infernal yells followed close on the heels of the fugitives very few of whom received quarter”—finishing them off with tomahawks. Winchester was captured by the Wyandot chief. Not long after, the 385 men of the Kentucky Rifle Regiment in Frenchtown, eager to fight but without ammunition, surrendered on Winchester's order. British losses were 24 regulars and militia killed, with 161 wounded. Indian losses are unknown, while the American loss included 500 prisoners and 400 killed or massacred, 60 of these being wounded men left in Frenchtown and murdered by the Indians.

In the meantime, Harrison had arrived at the Grand Rapids with 900 men. Upon learning of Winchester's debacle at Frenchtown, he withdrew 15 miles to the south. Proctor, his force mauled in the recent contest, heeded his cautious nature and retreated back to Fort Malden. On February 1, 1813, Harrison and 2,000 men returned to the Rapids and constructed Fort Meigs on the south side of the Maumee River as an advanced base, but his effort of the last five months to reach Fort Malden had ground to a halt.

In early 1813, US President James Madison selected John Armstrong, a US Army Brigadier-General and commander of the defenses of New York City, and member of an anti-Madison faction of the Republican Party, as the new Secretary of War. Born on November 25, 1758 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he joined the Continental Army in 1775, serving at the battles of Trenton, Princeton and Saratoga. Mustered out of the army as a major, Armstrong showed a canny knack for intrigue. Moving to New York, he joined the Republican Party, supported Thomas Jefferson for President, and served as US Senator from the Empire State, as well as American Ambassador to France. As the chief administrator of the War Department, he sought to be the nation's primary military strategist by personally directing the movements of the principal armies. He also harbored presidential ambitions.

Along with a new Secretary of War came an effort to increase the size of the American army. During the first months of 1813, Congress authorized the creation of six new major-generals, eight additional brigadier-generals, and an increase in the strength of the army from 35,752 to 57,351.

Re-enactors recreate 6th US Infantry Regiment at drill.

Re-enactor holds Brown Bess musket. He recreates a British private of the 8th (King's) Regiment of Foot.

“Harrison's army is for all purposes dissolved,” wrote an officer on the General's staff in late February 1813, because, as he complained, “his Ohio and Kentucky militia finished their six months service and have happily returned home.” The War Department's new campaign blueprint for Harrison was based on control of Lake Erie. Once this was accomplished, he would transport his force by water, assuring the capture of Detroit and Malden, as well as securing the frontier. The administration decreed he could have no more than 7,000 men, since his British opposition in the area numbered no more than 2,000, and because the United States Treasury could not afford to maintain a larger force in the west.

Harrison's opponent, Henry Proctor—recently promoted to Brigadier—understood the dual threat the Americans posed to Fort Malden: Fort Meigs as a base for a land or sea assault, and Presque Isle where construction of enemy ships menaced British control of Lake Erie and thus Upper Canada. While the garrison at Meigs was weak—just 500 men through March—and Presque Isle was defenseless, Proctor did not strike by using his control of the lake to concentrate his forces for an assault on either American position. The more important target was the US naval base, which if taken would have assured British dominance of Lake Erie, and thus the safety of Fort Malden. But Proctor remained inactive, pleading he could undertake no offensive moves due to lack of supplies, transport and poor weather. He blamed his superior, the new British commander of Upper Canada, Major-General Francis de Rottenburg, for the first two impediments.

Battle of Fort Stephenson, August 2, 1813, in which the British aided by Indians led by Tecumsehattacked the fort on the Sandusky River but were repulsed.

De Rottenburg came from Poland, and gained his first military experiences in the French Army, but he moved on to the British Army and was promoted Major-General in 1810. In Canada, he exhibited proven combat leadership as well as administrative skill, and succeeded Isaac Brock as head of Upper Canada in June 1813. His first inclination after taking over responsibility was to abandon the province. He did not do so, but that initial mindset may have been the reason he failed to provide Proctor with the means to tackle Fort Meigs or Presque Isle. His performance in 1813 showed him as “the solid but un distinguished Baron [who] exhibited few signs of brilliance, originality or forceful determination.”

Proctor's reluctance to move ended on April 24, when he left Fort Malden with 984 regulars and militia, sailed down the Maumee, was joined by Tecumseh and 1,200 Indians, and landed below Fort Meigs. On May 1, his seven heavy guns commenced bombarding the American fortification, constructed of earth and heavy logs on a bluff 60 feet above the Maumee. Surrounded by the river on its north, to the east and west by deep ravines, and on its southern face by a log palisade, its garrison numbered 1,100 men and 30 cannon.

For seven days, the British bombarded the American position that had been strengthened by a traverse—a high protective wall of earth the length of the camp. According to Proctor's report, the traverse was so effective “as to render unavailing every effort of our Artillery.” Frustrated by the strong defenses, Tecumseh dared Harrison to come out and give battle, and not hide “behind logs and in the earth like a groundhog.” Harrison wisely refused, expecting a relief column of 1,200 Kentucky militiamen under Brigadier-General Green Clay any moment. With them, he planned a counterattack, taking 800 of Clay's men down the Maumee and attacking the British batteries on the north bank, while other Kentucky militia came ashore on the south side. After both groups were established on land, Harrison would lead a sortie from the fort to join them.

On May 5, the American force landed on the north shore and took the enemy guns, but before spiking them set about chasing the Indians in the area. Proctor hit back, recovered his artillery, and after a vicious fight killed 200 of Clay's men and captured 500 more. Proctor lost 50 men, not including Indians. Meanwhile, the American party that was to land on the south side of the river was prevented from doing so by the strong current, making their way instead to Fort Meigs. A third contingent tried to land on the north bank to help their beleaguered comrades, but was forced to escape to the fort. Harrison, witnessing the plight of this last group of Americans, sent out 350 men from Meigs to take an enemy battery on the south side of the river. This unit, under Colonel John Miller, succeeded in reaching and spiking the guns but had to retreat when attacked by an overwhelming number of Indians. As at Frenchtown, after the battle Americans captured on the north bank were murdered by the Indians until Tecumseh halted the massacre.

On May 9, Proctor gave up his siege and returned to Fort Malden. His Indians were leaving him, the Canadian militia clamored to be released to go home to put in their crops, and many others were down with sickness. A pause now settled over major operations in the Northwest. Harrison was ordered to assume the defensive until Lake Erie was in American hands and his army's ranks were filled. Proctor, soon promoted to Major-General, did not stir because little by way of additional men and material reached him due to pressure exerted on the British along the Niagara front.

On the Niagara front, Major-General Henry Dearborn set up camp at Four Mile Creek with 4,700 American troops poised to strike the British bastion of Fort George four miles to the east. Dearborn's new chief-of-staff was Colonel Winfield Scott. Born in Virginia on June 13, 1786, Scott was an attorney before entering the US Army in 1808 as a Captain, rising to Lieutenant- Colonel in 1812. Captured at the battle of Queenston, he was exchanged in March 1813 and promoted Colonel. His natural leadership abilities, combined with great physical bravery, indomitable will and aggressiveness made him the driving force behind the timid, unimaginative Dearborn.

Scott's plan for the capture of Fort George called for transporting troops from Four Mile Creek along the shore of Lake Ontario and landing them behind the fort. Close coordination between the army and the supporting naval force was required. Scott would command the lead elements of the attackers. Defending the area around Fort George with 1,800 British regulars, 500 militia, and 100 Indians was Brigadier-General John Vincent. Modest and well liked, the Irish-born Vincent was a capable, if not exceptional, military leader.

Fort George, Lake Ontario, captured by the Americans from the British on May 27, 1813. Now a preserved national site.

Naval cannon mounted on section of reconstructed battlements at Fort George.

At 3:00am on May 27, American troops shoved off in boats on Lake Ontario while warships silenced the two British batteries defending the landing beach. Oliver Hazard Perry directed the naval gunfire and the movement of the soldiers to shore. Vincent had determined to meet the American assault on the beach and placed almost his entire command there. Colonel George McFeely, 22nd US Infantry Regiment, was in the first assault wave and remembered that, as his men pulled for the coastline, the enemy “lay in waiting in a ravine 40 yards from the shore. They reserved their fire until our boats were within 150 yards when they opened a heavy and galling fire.” He reported that, upon reaching the shore, “the action was very close and warm for about ten minutes after we landed, when the [British] army gave way and retreated in confusion.” As the Americans hit the beach, the US Navy, according to a sailor called Myers, “kept up a steady fire with grape and canister, until the boats [small landing craft] got in shore, and were engaged with the enemy, when we threw round-shot over the heads of our men, upon the English.”

Other accounts of the initial American landings paint a picture of a hard fight to secure the beachhead. As the American advance guard, led by Scott and Perry, set foot on land, they were met by British defenders atop a 12-foot embankment who pushed them back with a bayonet charge. Scott held his nerve and led a successful countercharge that drove the enemy from the high ground. Outnumbered by the American troops coming ashore and suffering from the supporting fire of several US Navy schooners, the British, after two valiant but fruitless counterattacks, broke and left the field. Soon after, Vincent ordered the abandonment of Fort George, Chippawa and Fort Erie, and moved his command 18 miles beyond Queenston to his supply depot at Beaver Dams.

Having secured Fort George, Scott continued in pursuit of Vincent until told to terminate the chase, for fear of ambush, and return to the fort. The capture of Fort George cost the Americans 40 killed and 113 wounded, compared to a British loss of 108 killed, 163 wounded, and 115 prisoners—all regulars—as well as most of the militia captured. The British abandonment of Fort Erie freed the American naval force at Black Rock, allowing US ships safe passage to Presque Isle. However, the true objective of the operation, the elimination of Vincent's command, was not obtained and would remain a serious thorn in the Americans' side.

Had the Americans been firmer in their pursuit of Vincent after Fort George, claimed Lieutenant-Colonel John Harvey, the British army would have been “caught under a circumstance of every possible disadvantage.” One of the best British officers in North America, Harvey, General Vincent's second-in-command, was in a position to know. Destruction of Vincent's Niagara army would have left Proctor in the west isolated, and all Upper Canada exposed to American aggression. Instead, the army under Vincent would live to fight another day.

On June 1, 1813, General Dearborn decided to complete the unfinished business of eliminating Vincent's army, which had withdrawn to Burlington Heights at the western tip of Lake Ontario. He sent out 1,400 men, under Brigadier-General William Henry Winder, from Maryland to finish Vincent off. Although a Federalist, Winder was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel in the Regular Army in 1812, even though he had no military experience. After arriving near Vincent's fortified location, Winder realized that he was outnumbered and requested reinforcements.

Dearborn sent out Brigadier-General John Chandler, a Revolutionary War veteran with very limited military experience, who was a militia officer before the war. He assumed command of the expedition that had a combined force of 3,030 infantry, artillery, and cavalry. Upon studying the British position on Burlington Heights, Chandler decided not to make a frontal assault but to march from Stoney Creek to the lake, cross Burlington beach and cut Vincent's route to York.

On June 5, the Americans fought a sharp skirmish with an enemy picket formed by the Light Company of the 49th Foot, near Big Creek, forcing them to withdraw to a camp at Stoney Creek, 10 miles from Burlington Heights. The site was a good one with a 20-foot-high ridgeline to its front overlooking a grassland meadow; the American left rested on the high ground, the right was by a swamp. The troops were arranged with 800 men placed three miles from the main camp, the remainder in the encampment. The troops posted that night were as follows: the 25th US Infantry Regiment and the light troops on the right, the 23rd, 16th, and 5th US Infantry on the left. The artillery was placed in the center, but without support. Four hundred yards behind the artillery, Burn's Light Dragoons were camped. Surrounding the camp were scores of advanced pickets.

Line of British redcoat re-enactors advance against Americans in skirmish at Fort George.

Scots troops come under fire as they cross the frozen river at Ogdensburg in February 1813.

Responding to the American presence, Vincent approved Colonel Harvey's plan for a night attack with 766 men, with Harvey leading the assault. At 2:30am the British attacked, guided to their objectives by American campfires. As the British approached, some of their staff officers started to cheer in violation of Harvey's “perfect order and profound silence command.” British Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon, 49th Foot, heard the shouting and recalled, “The instant I heard their shout I considered our affair ruined.”

The alerted Americans sprang up and commenced firing at their attackers. The Redcoats returned the fire against orders—the plan of attack being a swift advance with the bayonet. However, many of the American units were still surprised by the onslaught, one officer of the 2nd US Artillery Regiment recording that, “The enemy, with Indians, surprised with horrid yelling, and attacked our advanced guard, which we composed. We were able to make but a feeble resistance as the enemy was not more than 15 yards from us and obliged us to retire in great confusion.”

Upon hearing the noise of battle, Chandler took command in the center of the American line, while Winder took over the left. Hearing firing from the right, Chandler galloped in that direction but was badly injured when his horse threw him. Limping back to the center of the line, he arrived to find his artillery had been captured by the British, and he was soon taken by the enemy as well.

At the start of the battle the British had made little headway as they exchanged fire with the more numerous US troops. The Americans, Harvey recalled, “poured a destructive fire of musketry upon us, which we answered on our part by repeated charges whenever a body of the enemy would be discerned or reached.” American Colonel James Burn said that during the one-sided firefight, “the enemy attempted by frequent charges to break our line, but without effect, being obliged to give way by the well-directed fire of our brave troops.” Entire British companies, torn by American musketry, began to retreat just half an hour after their initial assault. At this point, soldiers from the 49th Foot, under Major Charles Plenderleath, charged the center of the American line to silence the artillery that was taking its toll on the attackers. The Major lost his horse and was wounded twice, but his action retrieved British fortunes from the edge of disaster. These were the soldiers who took Chandler captive. Not long after Chandler was taken, Winder rode to the American center and was also taken prisoner.

Although the official reports differed—the Americans saying they repulsed the British, while the British claimed that the Americans were routed—it appears that both sides were in retreat at the climax of the fight, and that the British thrust at the US artillery gave them time to take away two artillery pieces and some prisoners. With their generals captured, command of the American army devolved on Colonel Burn, 2nd US Light Dragoons. He withdrew his force a mile from the battlefield to reorganize, admitting in a private letter that he was “at a loss on that occasion” as to what to do. Burn then ordered a withdrawal to Forty Mile Creek, since the army was nearly out of ammunition, and completely out of generals.

Both sides rallied by dawn, so both claimed victory even though the battle was a draw. The British commander, Vincent, had played little part in the drama since early on he was thrown from his horse, disoriented by the fall, and spent most of the day wandering in a wood several miles from the battlefield. He was discovered by his men later that day. The British marched to Stoney Creek after their demoralized, leaderless opponents vacated the spot. American losses were 17 killed, 38 wounded and 113 captured. The British lost 23 killed, 136 wounded and 55 missing.

In the second week of June, Royal Navy Captain James Yeo had gone to aid Vincent in the western part of Lake Ontario. Instead of following him, the American Commodore Issac Chauncey stayed snugly in Sackets Harbor, thus giving the British control of the lake by default. Vincent took the opportunity the American naval leader provided him by advancing from Stoney Creek east to Beaver Dams. Responding, Dearborn pulled his forces back toward Fort George, relinquishing almost all the territory the Americans held west of the Niagara River, including Fort Erie. On December 10, Fort George was abandoned by the Americans, followed on the 18th by a daring British night attack that captured Fort Niagara, on the US side of the Niagara River, and its 400-man American garrison.

With Dearborn again ill and Chandler and Winder in British captivity, Brigadier-General John Parker Boyd became de facto regional commander. Desiring to gain elbowroom and raise the spirits of the troops, Boyd dispatched a force to attack an enemy post at De Cou's House, 12 miles from American lines. Boyd had served for 20 years as a mercenary for feuding princes in India after leaving the United States army in 1789. In 1808, he rejoined the army as a colonel, and fought well at the battles of Tippecanoe and at Fort George under Dearborn. He was made Brigadier-General in the regular army in 1812.

Indian allies of the British attack Fort Dearborn (on the site of Chicago), August 15, 1813.

The force sent on the De Cou's House mission involved 575 men, including infantry, cavalry, and two artillery pieces under Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Boerstler, setting off on the night of June 23. His march put him beyond any supporting friendly units. That night, too, a woman named Laura Secord, the wife of a Canadian militia officer, had learned of the Americans' plans had gone to warn the British. The next day, upon reaching Beaver Dams, the Americans were ambushed by 465 Indians and surrounded. The fight had been going on for three hours when a detachment of British regulars under Lieutenant Fitzgibbon appeared and demanded the Americans surrender, threatening a massacre by the Indians if they continued to resist. Boerstler threw in the towel and he and his men became prisoners of war. Fitzgibbon later reported that: “Not a shot was fired on our side by any but the Indians. They beat the American detachment into a state of terror.”

The fight at Beaver Dams brought Dearborn's Niagara Campaign to an inglorious end. It also gave Secretary of War Armstrong the excuse to relieve Dearborn from command, replacing him temporarily with Boyd. No further reverses came to American arms in the summer of 1813 since the new British commander of Upper Canada—Major-General de Rottenburg—was as lacking in enterprise as his American counterparts.

“The loss of the fleet is a most calamitous circumstance,” wrote British Brigadier-General Proctor. “I do not see the least chance of occupying to advantage my present extensive position.” American control of Lake Erie completely isolated the British in Western Upper Canada from supplies and manpower coming from the east. Proctor's 900 regulars and 1,100 Indians were no match for Harrison's reported 6,000 troops. Proctor abandoned Amherstburg and Fort Malden on September 24 and took up the 70-mile march to the lower Thames River Valley as a preliminary move further east to join Vincent. Outraged with what they considered the British Crown's abandonment of their cause, Tecumseh and many of the Indians only reluctantly joined the British retreat.

After occupying Fort Malden on the 27th, the American pursuit of their enemy did not commence immediately. Harrison wanted to lead off the chase with Colonel Richard M. Johnson's 500-man well-trained and equipped Kentucky Mounted Rifle Regiment, which did not reach him until October 1. Next day the American army, 3,500 strong, moved out. By the 3rd, Johnson, supported by Perry's gunboats, was nipping at Proctor's heels despite the week's head start the British had on their pursuers. On October 5, the British and their Indian allies, including the women and children that had accompanied their supply train, took up a defensive position on the north bank of the Thames, two miles west of the village of Moraviantown. Proctor placed the 41st Foot, formed in two lines in open order formation—one behind the other 200 yards apart—on his left in a wood next to the Thames. To Ensign James Cochran of the 41st Foot, the British formation was not a reliable one, noting that “the order of the lines was neither extended nor close but somewhat irregularly between both, and the trees were not sufficiently large to afford protection.” The Indians were posted on the right on the edge of a swamp. One six-pounder cannon was planted on the road in front of the 41st. Proctor's force numbered 430 regulars and 600 braves.

American cavalry clash with British-allied Indians at the battle of the Thames, October 5, 1813.

Harrison planned to send his regulars, under Lewis Cass, against the 41st while his militia masked the Indian position. Johnson was to be held in reserve. But Johnson, the amateur soldier and sitting US Congressman from Kentucky, proposed that he be allowed to initiate a mounted charge on the spread-out Redcoats of the 41st. After receiving Harrison's bemused approval, Johnson sent his battalions straight at the British. Shouting “Remember the River Raisin!” the black-clad riders charged, were halted by enemy fire, but charged again, breaking through both British lines, then wheeled right and left to bring rifle fire on the Redcoats from the rear. Upon contact with the onrushing horsemen, according to Private Shadrach Byfield of the 41st Foot, “After exchanging a few shots our men gave way.” The lone British artillery piece never got off a shot, since it was dragged into the wood by its startled team. In five minutes, at a cost of three wounded Americans, the fight ended with the British surrendering.

Turning now to the Indians, Johnson spurred his horsemen into the swamp and was received by a deadly musket volley, which dropped most of the Kentucky vanguard and wounded Johnson. The area was too thick for effective mounted action, so Johnson ordered his men to dismount, and a furious firefight, along with many hand-to-hand combats, ensued. Tecumseh was in the act of rallying his warriors when he was killed by a musket ball. Upon his death, recalled Kentucky Private William Greathouse, the Indians “gave the loudest yells I ever heard from human beings and that ended the fight.” Reinforced by more American regiments, and with some of Johnson's men gaining their rear, the Indians broke and fled through the forest.

The Battle of the Thames was concluded in less than an hour. American losses were 12 killed and 22 wounded; the British lost 12 killed, 22 wounded, and 579 captured; the Indians 33 killed, including Tecumseh. Proctor and 246 soldiers, and the accompanying women and children, escaped to Burlington Heights, reaching there on the 17th. Fearing a further advance by the Americans, Prevost ordered the evacuation of Upper Canada up to Kingston. But Harrison, instead of continuing on, returned to Detroit. He did so because his militia's term of service was about to expire and he would not have the men to follow Proctor. It was also obvious that the British and Indians would no longer be a threat to the Northwest. By mid-October most of the latter had entered into an armistice with the United States. The fighting in the west was over. Attention now turned to the east.

Upon learning that Dearborn had been replaced by Major-General James Wilkinson, an army wag quipped that “age and fatuity were being replaced by age and imbecility.” James Wilkinson—a confident man in uniform, as well as being a paid agent of Spain—was born in Maryland on January 1, 1757. Present with Benedict Arnold during his Quebec Expedition, then a captain in the Continental Army, he was made brevet Brigadier-General in 1777 after working on Horatio Gates' staff. Charges of financial corruption caused him to leave the Army in 1781, whereupon he moved to Kentucky, then New Orleans, where he worked as a spy for the Spanish in return for being allowed by them a trade monopoly. Returning to the US Army in 1792, he was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel, then Brigadier-General in 1796—the most senior army officer in the country. As governor of the Missouri Territory he renewed his ties as a Spanish agent and plotted to create a breakaway state allied to Spain in the southwest. As head of the Seventh Military District at New Orleans, he occupied Mobile for the United States in April 1813. In July of that year he was promoted Major-General and tasked with conducting a campaign against Montreal.

The offensive was planned by Armstrong who envisioned a two-thrust operation: Wilkinson moving from Sackets Harbor in a flotilla of small craft that would transit the St. Lawrence River, while a second column marched up the Champlain River Valley into Lower Canada to rendezvous with him. The forces would then unite for the drive on Montreal, which along with Quebec, was the most important British supply and staging area in North America. The commander of the second prong of the offensive was Major-General Wade Hampton, whose hatred of Wilkinson only made the already quixotic attempt on Montreal more misguided.

Raised in South Carolina, Hampton had fought as a partisan during the Revolutionary War, distinguishing himself at the battle of Eutaw Springs. After that conflict, he amassed a huge fortune selling cotton. He won a seat in the US House of Representatives, and was then made Colonel of the Regiment of Light Dragoons. In 1809, he became a Brigadier-General and succeeded Wilkinson as commander in New Orleans, where he and Winfield Scott gained his predecessor's enmity by exposing the poor administration of his command. In March 1813 he was promoted to Major-General and was transferred from Norfolk, Virginia to Burlington, New York in preparation for an eventual attack on Lower Canada. Flatly refusing to obey orders from Wilkinson who was his senior, Hampton was talked into cooperating with him only by being promised that his orders would come through Secretary of War Armstrong.

The operation was held in abeyance until the American troops under General Boyd at Fort George could be ferried to Sackets Harbor. That was made possible after a daylong sparring match between the ships of Chauncey and Yeo's squadrons on September 28 near Burlington Bay, which resulted in the British retreat to Kingston, thus giving temporary control of Lake Ontario to the United States. Although Armstrong wanted to first take Kingston before heading for Montreal, he changed his mind upon learning on October 16 that the former had been heavily reinforced. By that same date, according to his later writings, he felt Montreal could not be taken so late in the season, and gave instructions for the preparation of winter quarters for his troops of the Northern Army, a clear admission that the invasion of Canada was being suspended. But political pressure was growing for the American Army to go on the offensive, and Armstrong and Wilkinson bent to that pressure. The invasion, which should have been shelved, was on again even though winter was near.

Wilkinson's 8,000-man army left Sackets Harbor piecemeal, starting up the St. Lawrence on October 16, with the whole to concentrate at French Creek—modern Clayton, New York. Meanwhile, Hampton had crossed into Lower Canada on September 19. Looking for water for his men, he marched his 4,000 raw recruits 40 miles west to the Chateauguay River. Waiting there for him, only 35 miles from Montreal, was Lieutenant-Colonel Charles-Michel de Salaberry, a native of Quebec. The Colonel had joined the British Army in 1792, fought in the West Indies, Ireland and Holland, and was sent to Canada in 1810.

Taking station with his force of 1,800 regulars and militia, where the 100-foot-wide, six-foot-deep water course made a sharp bend, de Salaberry set up a two-mile-deep defense with a number of wooden breastworks to the rear of an abatis—his left was shielded by the river, his right by a marsh. Across the right bank of the river, he placed 160 men to guard a ford located two miles behind his forward defense lines.

Upon Hampton's approach to the Chateauguay on October 25, he detached 2,000 men under Colonel Robert Purdy to cross the river and head for the ford behind the enemy. This force advanced only five miles before becoming disoriented, ending up not behind the Canadians but along the river opposite de Salaberry's first defensive line. During midmorning on the 26th, the Americans of Brigadier-General George Izard's 2nd Brigade took position opposite the abates. Izard made a demonstration with his 10th US Infantry Regiment, slowly reinforcing his line with other units. Reacting to this move, de Salaberry moved men to the first defensive position, stationing himself there as well. He then ordered his bugler to “sound for commence firing and a brisk little action took place.”

At 11:00am, Purdy's 1st Brigade marched for the ford, his advance elements running into a British militia company on the right side of the river. A 20-minute firefight broke out, and according to Sergeant Neff, US 4th Infantry, it was a “furious action supported with firmness on both sides when we charged the enemy and drove him off.” Actually, both parties were shaken and retreated. Hampton soon cancelled his plan to take the ford, recalled the 1st Brigade, and ordered it to pull back a few miles and re-cross to the left bank of the river.

At 2:00pm, Izard was directed to attack the enemy abatis. The general formed his three regiments in line and let loose a series of volleys. Corporal Bishop, 29th US Infantry Regiment, remembered that his unit “first halted under the brow of a hill and was ordered to load our muskets at which time the battle commenced at a very hot note.” Returning fire in front of the abatis were the Canadian Fencibles, whose aim was good, with many American wounded being hit in the head or chest. The exchange of fire then slackened as both sides turned their attention to the other side of the river.

On the right bank, as Purdy recorded, “The enemy made a furious attack on the column by a great discharge of musketry, accompanied by the yells of savages.” The order to retreat was then heard, and the 1st Brigade, abandoned by many of its officers who had left the battle previously, recoiled. Some rallied and these fended off a charge by the Canadians, pursuing them to the Chateauguay where the Americans were fired on by Canadian Voltigeurs across the river. This “checked their career,” said one soldier, “and threw them back in the greatest confusion.” After that, Purdy's outfit was out of the fight.

At 3:00pm, Hampton ordered Izard to disengage his men and retreat three miles to their camp. He failed to inform Purdy of this move, leaving the 1st Brigade isolated on the other side of the river until it crossed and joined Hampton next day. De Salaberry and his victorious command remained in their position for the next eight days just in case the Americans returned. The Canadian casualties at the battle of Chateauguay numbered five killed, 15 wounded, and four missing; the Americans lost 50 officers and enlisted men.

After this humiliation, Hampton withdrew from Canada to Plattsburg, New York and entered winter quarters. Soon thereafter, he refused to obey an order from Wilkinson to move his army to Canada and join him. He then tendered his resignation and left the army. As Hampton marched out of Canada, Wilkinson and his army, escorted by 12 gunboats and 300 small craft, marched in. Not until November 6 did the expedition, lashed by gales and snowstorms, approach Prescott, 60 miles from their starting point at Sackets Harbor.

On October 17, de Rottenburg got wind of Wilkinson's move, and dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Joseph W. Morrison, 89th Foot Regiment, with 630 men and two light artillery pieces on several schooners and gunboats, to act as a corps of observation to dog the American force. Next day, augmented by men and additional cannon, Morrison landed his 1,200 troops at Prescott, behind the Americans. The escorting gunboats, under Captain William Howe Mulcaster, Royal Navy, continued to shadow the enemy and harass the American craft on the St. Lawrence.

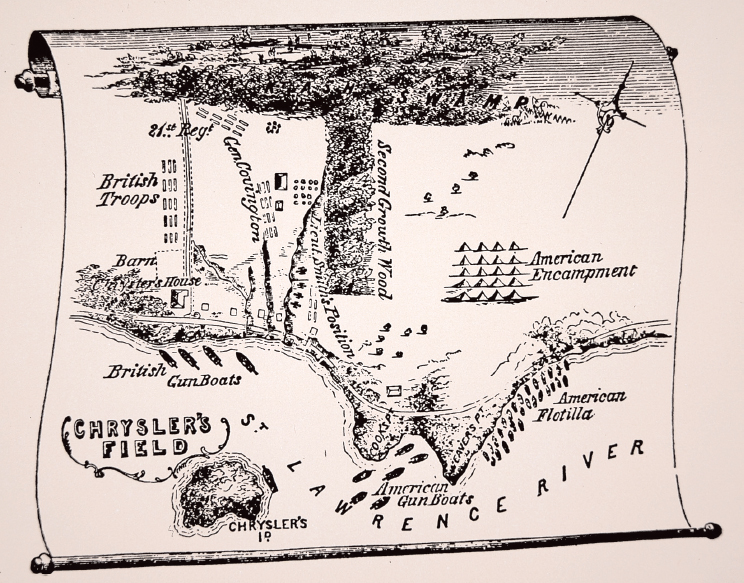

Positioned at the John Chrysler farm, Morrison took up a position in case the Americans decided to turn on him. Just to his rear was a dirt road which aided lateral movement along his line; a log fence lining it provided good cover. To his left was an impassable swampy pinewood a half-mile inland. To the front of the British were a ploughed field, two gullies, and a large ravine that bent down to the river. Morrison placed the bulk of the 89th and 49th Regiments north to south along the dirt track. Captain George W. Barnes' three companies of the 89th, two companies of the 49th, and two of the Canadian Fencibles under Thomas Pearson were placed behind the first gully; Fraser's dragoons at the ravine; Frederick Heriot's light troops above the ravine in the woods; and two guns on the right of the main line, and one with Pearson. Thirty Mohawk Indians were in the woods on the extreme British left.

On the 11th, a gray Thursday, the American army was on the north shore of the river while their boats navigated the Longue Salte Rapids. Serving as the rearguard was Boyd's division, three brigades and 3,000 men strong, with orders that “should the enemy harass the rear,” Boyd was to “turn and beat him back.” At 2:00pm, Brigadier Robert Swartout's 4th Brigade, Boyd's Division, came to the aid of American pickets being pressured by Heriot's light troops and the Mohawks. He was followed by Brigadier-General Leonard Covington's 3rd Brigade, with Colonel Isaac Coles's Brigade moving on his right. The men of the 3rd and 4th Brigades became disorganized due to the rough terrain and effective skirmishing from Heriot's men, but forced the British back. As the three American units cleared the woods, they found themselves in front of the main British line across a large open field.

Seeing the Americans leave the woods, the 49th and 89th moved forward and deployed in a line of two ranks. The approaching Americans were an imposing sight, with one Sergeant of the 49th exclaiming that “there are too many, we shall be slaughtered!” As the Americans came on, they were hit by a “heavy and galling fire” from the British artillery on the field and from Royal Navy gunboats.

The American infantry tried to form and return fire but were unable to properly do so. One US officer remarked that “we could not recover any order.” Coles's men, marching between the other brigades, became so disordered that according to Lieutenant Joseph Dwight, 30th US Infantry, the men “retreated in great disorder” under the artillery fire. Only with difficulty were the Americans rallied.

Boyd ordered Swartout and Coles to attack the British left flank. The former advanced and then began to deploy into line but became disorganized. The left flank companies of the 89th swung 90 degrees back and delivered a lethal volley at the struggling Americans, which staggered Swartout's front ranks. The shattered formation retreated, colliding with Coles's Brigade and sending the lot to the rear in panic.

Meanwhile, Covington's 3rd Brigade steered for the ravine and forced that position. Morrison, seeing the threat to his right, sent his main line to confront the US 3rd Brigade. The opposing lines closed to within 100 yards, with the Yankees firing “irregular, a pop, pop, popping all the time,” according to a British officer, while the Redcoat volleys were “all together and at regular intervals like tremendous rolls of thunder.” The exchange lasted 15 minutes before the American ranks were thinned and their ammunition exhausted. According to Colonel Cromwell Pearce, 16th US Infantry, they “deemed it proper [for the division] to return to the ravine.” The Americans—the three brigades mixed up—gained the ravine, and a stalemate between the opposing infantry ensued.

Map of battle of Crysler's Field (spelled wrongly here), November 11, 1813.

At 3:30pm, some relief was afforded the Americans by the arrival of four six-pounders, which began shooting at the 49th Foot. Tormented by the enemy fire, the 49th attacked the guns but were thrown back with loss. Morrison mentioned the attempt on the American artillery when he wrote that the 49th was “directed to charge the guns posted opposite to ours, but it became necessary within a short distance to check the forward movement in consequence of a new threat.” John Sewell, an officer in the 49th, identified the threat when he observed American cavalry “galloping up the high road” directly at the 49th's right flank.

The 2nd Light Dragoon Regiment, under Major John T. Woodford, was propelled forward in order to save the US artillery now being threatened by a renewed British attack, this time by parts of the 89th Foot. Thundering onward, they were struck by canister from British artillery, as well as musket balls from Barnes' soldiers. Shaken, the blue-clad horsemen continued on and were almost upon the 49th's right flank, when the latter swung back, and, as stated by Lieutenant Sewell, “poured in [a] volley” at them at the same time as Barnes fired into their rear. The dragoon's formation fell apart, those not shot from their saddles running for the ravine. Woodford continued to ride forward, and again according to Sewell, “leapt over the fence and was riding toward our right, but alone; some of the men rushed out to attack him with their bayonets fixed, but observing that he was unassisted he took the fence again in good hunting style and followed his men who were in good retreat.” The American riders lost 18 killed and 12 wounded. However, the charge had not been in vain as it allowed three of the four American guns to escape capture.

With the enemy cavalry gone, Morrison moved his entire force west of the ravine to continue the contest. Boyd was of another mind. Feeling he had executed his orders from Wilkinson to drive away any probing enemy, he related, “I ordered the main body to fall back, and reform where the action first commenced”—in other words, at the edge of the woods. His three brigades duly turned and marched to the forest. With a fresh supply of musket balls on hand, men and officers expected to renew the battle, but it was not to be. Boyd received an order to fall back to the American boats where the army would be moved two miles downriver and landed on the US side. His division formed a column of march and proceeded as instructed. After two hours and 20 minutes, the battle of Chrysler's Farm, the most critical battle fought during the War of 1812, was over. Montreal was never again seriously threatened. British battle losses totaled 22 killed, 148 wounded and nine missing; the American army had 102 killed, including General Covington, and 237 wounded.

Wilkinson received a letter from Hampden on the 12th that gave him the excuse to terminate the operation. Hampden's missive explained that since Armstrong did not think taking Montreal was feasible, therefore Hampton was not going to join Wilkinson in Canada. Wilkinson's army wintered at French Mills on the Salmon River. Most of the British force opposing him returned to either Prescott or Kingston. Thus the year ended with America's gains on the Niagara forfeit, the St. Lawrence Campaign a failure, and its total war effort at its nadir.