THE WAR “SEEMS TO ASSUME A NEW AS WELL AS MORE ACTIVE AND INVETERATE aspect than before,” wrote Admiral Warren to the British Admiralty on October 5, 1812. His assessment was correct—the Madison administration was adamant in prosecuting the war as long as Britain refused to renounce impressments, and Yankee privateers were menacing British maritime trade from the West Indies to the St. Lawrence River. Just as enraging was the fact that the upstart American Navy had won two single-ship actions. To rectify this unexpected situation, His Majesty's Royal Navy installed a new chief of the North Atlantic Station with authority over the entire United States coastline from Maine to Louisiana, all the inland lakes, and the West Indies.

John Borlase Warren had been in the Royal Navy since 1771, starting as an able seaman. From an aristocratic family, he had been a Member of Parliament, and in 1810 was made Admiral after almost 40 years serving at every command level in the navy dating back to the American Revolution. Two years later, the 59 year-old—known more his for diplomatic and administrative capabilities than his combat skills—was placed in charge of the naval effort against the United States.

By 1813 Warren had instituted a multi-faceted program to combat American naval activities. They included sealing enemy warships and privateers in port, assuring British naval dominance on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, and creating a blockade of all principal ports south of Rhode Island, including the Mississippi, to put “a complete stop to all trade and intercourse by sea and with these ports.” At first, New England was treated differently. The British government wanted all US naval operations from those anchorages halted, but not commercial traffic. To that end, New England separatism was to be encouraged by the generous issuance of trading licenses allowing them to carry on commerce with Britain.

Safeguarding Britain's trade traffic in his area of authority was also the Admiral's responsibility. This included providing escorts for ship convoys when needed. Lastly, he was tasked with pinning down enemy ground forces along the coast through amphibious raids, so they could not be used against Canada. For this purpose, in 1813, two Royal Marine battalions were transferred from Spain and Holland—a total of 1,600 men—to work directly with the British fleet in American waters.

To accomplish the blockade of the American East Coast, Warren commanded, early in 1813, 97 warships ranging from ships-of-the-line to frigates to brigs and sloops. However, the size of the British contingent could do little against adverse weather and prevailing tide conditions, especially during the winter months of November to March, when contrary winds blew ships off their stations, and the same winds, accompanied by thick fog, enabled American warships and commerce marauders to escape port.

As Warren scrapped together an effective naval force to blockade the United States and control the inland lakes, American naval action was taking a new turn. In December 1812, Paul Hamilton was replaced by 52-year-old William Jones as Navy Secretary. Pennsylvania-born, he served in the Continental Army at the battles of Trenton and Princeton, and was later a lieutenant in the Continental Navy. During the inter-war years he was involved in the mercantile trade. As a Republican, President Jefferson offered him the position of Secretary of the Navy in 1801, but Jones declined. On January 12, 1813, he accepted the job from President Madison.

Jones fashioned his country's naval war strategy. He strengthened the impact of the country's weak coastal defense gunboats by concentrating them at the most important ports and regions, including New York, New Orleans, the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays, and the coast of Georgia. He favored single warship cruises of guerre de course—raids on commercial shipping—and wrote to his captains saying that his intention was “to dispatch all our public ships, now in port, as soon as possible, in such positions as may be best adapted to destroy the commerce of the enemy.” He felt sloops were the best type of ship for this activity and pushed for their construction. The Secretary wanted to avoid combat between the small number of US war vessels and the superior British fleet. He also put together a sound program to build up American naval power on the Great Lakes. During his tenure as navy administrator, Jones presided over a proposed expansion of the US Navy, as per Congressional legislation passed early in 1813, which envisioned adding six 74-gun capital ships, six 44-gun frigates, and six armed sloops to the fleet. It was an impressive target.

“I would give all our prizes,” wrote the commander of HMS Shannon to his wife on September 14, 1812, “for an American frigate.” For months, Captain Philip Vere Broke and his ship—the 38-gun Shannon—had “sauntered about off Boston,” blockading that port, and as his letter stressed, he was eager for a fight. On May 3, 1813, the USS President, accompanied by USS Congress, broke out of Boston harbor, even though that port had been under the watchful eye of a powerful British blockading force including Shannon. The escape of the two American vessels left one US frigate still in the harbor—the 36-gun USS Chesapeake under Captain James Lawrence. It was the Chesapeake that Broke was eager to fight.

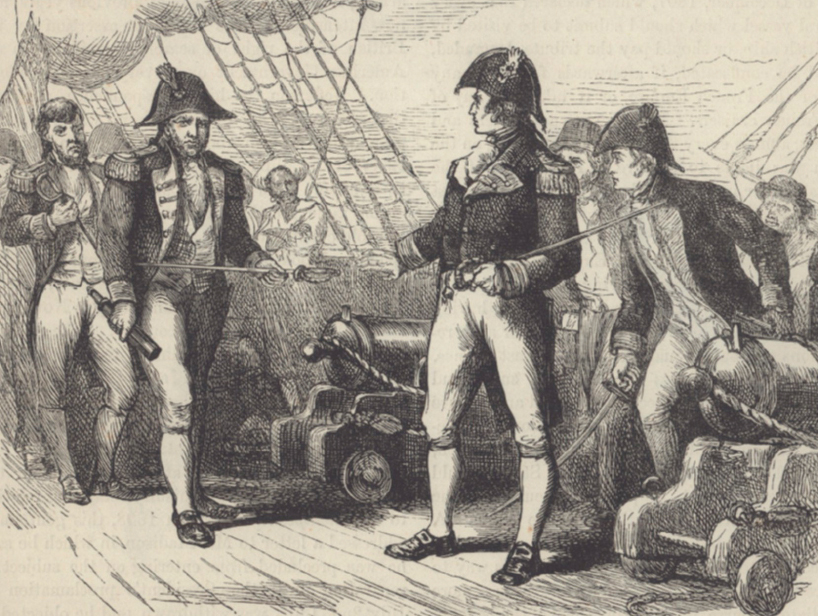

British Captain Philip Broke leads the boarding party that captures the Chesapeake.

In order to lure the American ship out of Boston, Broke wrote Lawrence a crafty and insulting letter challenging him to come out and engage in single combat with Shannon. As further inducement, Broke sent away all friendly ships in the area to assure his opponent it would be a one-on-one fight. Lawrence never received the challenge but, on his own volition, left Boston on June 1 and headed straight for Shannon seeking battle. As Chesapeake approached at 5:00pm, Broke told his crew, “Don't try to dismast her [Chesapeake]. Fire into her quarters. Kill the men and the ship is yours.” Chesapeake had the weather gauge and soon came up to her opponent, but instead of maneuvering to rake her stern, the Yankee came abreast of Shannon. At almost 6:00pm, the two vessels commenced trading heavy broadsides as Chesapeake inched parallel to her opponent. Soon both ships were damaged and Lawrence was wounded. His ship's headsail sheets were blown away, causing her to lift up into the wind, out of control, presenting her stern to the enemy and making it impossible for her to train more than a few cannon on her foe.

Captain James Lawrence, commander of the Chesapeake.

When Chesapeake's quarter galley collapsed on Shannon's bow, Broke ordered a 50 man boarding party to follow him on to the stricken American ship. The Yankee crew was also assembling a boarding party but the British captain moved quicker, and in minutes cleared Chesapeake's entire main deck. In the brutal hand-to-hand struggle, Broke was twice badly wounded by pistol ball and cutlass stroke, but was saved from fatal injury by the silk top hat he habitually wore. Before the boarding, Lawrence was mortally wounded, and before he was taken below decks he called to one of his officers, “Tell the men to fire faster. Don't give up the ship.” But exhortations were no match against the British assault, and 15 minutes after the battle commenced, Chesapeake surrendered. On June 6, she and the Shannon entered Halifax. The myth of American frigate invincibility had been dispelled by superior British gunnery. The bloody affair between Chesapeake and Shannon cost the Americans 47 killed, and 98 wounded, and the British 33 killed and 50 wounded.

The last six months of 1813 presented few bright spots for the US Navy. Captures were few and even getting out of port was difficult for American ships. After John Rodgers slipped out of Boston harbor on the President, he sailed for the West Indies, the Azores and Norway. He returned to Newport, Rhode Island that September after taking 13 prizes, including a small warship. Congress separated from President after leaving Boston. Her eight-month cruise bagged only four British ships. Stephen Decatur, leaving New York harbor in late May with United States, Macedonian and Hornet, was forced to run for New London, Connecticut, in the face of superior numbers of British vessels, and was promptly blockaded there. Constitution was trapped in Boston, Constellation at Norfolk, Virginia, and Adams in Chesapeake Bay.

Echoes of the glory days of 1812 returned with news of the exploits of the 14-gun USS Enterprise, whose commander, Lieutenant William Ward Burrows II, sailing from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, had orders “to proceed to sea on a cruise along the coast [of Maine]” to protect the coastal trade being “interrupted by small cruisers of the enemy.” On September 5, Burrows sighted the British 14-gun brig HMS Boxer, under Commander Samuel Blyth. Both ships were evenly matched. After a few hours of maneuvering out of cannon range, Burrows made straight for Boxer “with intention to bring her to close action.” Both vessels held their fire until they were running alongside one another at ten yards distance. The first exchange of cannon killed Blyth and mortally wounded Burrows. After a 15-minute duel, Boxer's rigging and topmast were gone, there was three feet of water in her hold, and she had ceased firing. The British vessel surrendered and was towed to Portland. The fight had cost the Americans three killed and 14 wounded, while Boxer lost four dead and 18 injured.

Death of Captain Lawrence on board the Chesapeake, his last instructions being: “Tell the men to fire faster. Don't give up the ship.”

Another American warship making a name for herself during a year of disappointment for the United States Navy was USS Argus, a 16-gun brig under Lieutenant Henry Allen. Leaving New York in June, Allen embarked on a commerce-destroying mission around the British Isles. In those waters, he captured 21 enemy craft, which he then burned. In response to the American's amazing success, the Admiralty sent HMS Pelican after her, under Commander John F. Maples. On August 15 they met off the Irish Coast, and although the opponents were closely matched, Argus was pummeled into surrendering after a brutal 45-minute close-action contest that might have gone either way. Argus lost six killed and 18 wounded, including the fatally wounded Allen, Pelican two dead, five wounded.

A third Yankee warship did considerable mischief during the last part of 1813. Captain David Porter, Jr. and his 32-gun frigate USS Essex had been on the prowl since it left the Delaware Capes in October 1812. Its mission was to engage in commerce raiding in the South Atlantic. Failing to rendezvous with William Bainbridge off the west coast, and then Brazil, Porter went off on his own, rounding Cape Horn and reaching Chile in March. He then set himself the mission of attacking the British Pacific whaling fleet, as well as English privateers stalking the US whaling flotilla.

Between April and October 1813, Porter took 12 enemy whalers and disrupted British whaling operations in the Galapagos Islands. After travelling to the Marquesas Islands, Porter arrived at Valparaiso, Chile, in February 1813. On March 28, after being cornered in the anchorage by two British warships for six weeks—the 36-gun Phoebe and 28-gun Cherub—Porter attempted to slip away, but lost his main topmast in a heavy squall. He was forced to enter a small bay outside Valparaiso where he was fired on by his opponent's longer-ranged guns. After enduring two and a half hours of punishing bombardment, the Essex surrendered, having lost 58 killed and 65 wounded. The British lost five killed and ten wounded.

The year 1814 saw a continuance of the war at sea. Evading the British outside Boston harbor, John Steward sailed USS Constitution to Guyana in January. For the next two months, he took only two merchantmen and an armed schooner. On one occasion, he attempted to overtake an enemy frigate, on another he escaped from two such vessels. In early April, he returned to Boston.

In late April, the first American sloop-of-war, the 22-gun USS Frolic set off for Cuba but was run down and captured. The sloop USS Peacock was much luckier, leaving New York to cruise to the Caribbean, where it captured 14 freighters. She also captured HMS Epervier, an 18-gun British brig, after a 45-minute duel, before returning to New York in October. USS Wasp, a 22-gunner under Johnston Blakely, set sail from Portsmouth in May. During her cruise, which took her to the English Channel and South America, she took 13 merchant vessels and defeated two British brigs—the Reindeer and Avon—before disappearing, mostly likely falling victim to a hurricane.

US officers on board the Chesapeake surrender their swords to Captain Broke.

During 1815, naval activity on the high seas continued, even though the final peace treaty between the United States and Great Britain was taking shape. On January 14, 1815, Decatur tried to leave New York harbor when his ship, USS President, ran aground, causing considerable damage and retarding her sailing ability. Next day, President was overtaken by three enemy ships, one of which, the 50-gun HMS Endymion, engaged her. President's heavy broadsides soon reduced the British vessel to a wreck. However, other enemy frigates came on the scene, and after belching their devastating iron broadsides into the struggling President, Decatur was forced to strike his colors.

Captain Charles Stewart, on the USS Constitution at this time, was out at sea, having departed Boston in mid-December 1814. By February 14, she was off the Spanish coast where she fought and captured two British warships—the 30-gun frigate Cyane and 18-gun sloop Levant—in the same battle. The last confrontation at sea occurred between the 18 gun USS Hornet and 18-gun HMS Penguin on March 23 in the South Atlantic. Within 25 minutes, the well-aimed fire of the American crippled her adversary.

Bitter battle between the two frigates USS Chesapeake and HMS Shannon outside of Boston on June 1, 1813.

As Secretary of the Navy, Jones wanted American privateers, in the form of ships, brigs, schooners, sloops and smaller craft, to harry the British commerce fleet. The result was the American capture of almost 1,400 vessels during the war. In contrast, warships of the US Navy took only 254 commercial and military craft during the conflict. With opportunities for legitimate shipping almost gone due to the British blockade, and the presence of British warships at sea, the American merchant marine turned to privateering with gusto. They often travelled in packs. Unlike the boxy bulk carriers of the European merchant marine, sharp-lined American brigs and schooners of less than 300 tons made good improvised privateers. Many of these privateers were large ships mounting 20 to 30 cannon. The seas around the British Isles proved to be some of the most lucrative hunting grounds for these American raiders.

Contrary to popular opinion, the successful privateer was in the minority. Of the 525 licensed privateers, only 207 ever took a prize. The most successful was the America, out of Salem, Massachusetts, which captured 41 enemy ships. Most holders of “letters of marque and reprisal” were traders whose main profit came from cargoes that successfully ran through the blockade, the letter of marque merely giving them the right to seize an enemy merchant vessel should the opportunity arise. It was a risky enterprise, as 148 American holders of letters of marque were captured, as well as two thirds of all their prize crews.

Overall, the effect of American privateers on British commercial trade was only moderate, with the number of British ships and tonnage actually rising during the war. In 1812, the British merchant marine had 20,637 ships, representing 2,263,000 tons of shipping. By 1815, the number of vessels had increased to 21,869, with total tonnage rising to 2,478,000. British imports and exports also grew from $60,000,000 and $48,000,000 in 1812, to $90,000,000 and $59,000,000, respectively, by 1815. America's guerre de course did, however, influence the final peace treaty. It softened Britain's terms for peace in light of the potential harm America could do in the future to her commercial sea trade in the form of lost profits, increased taxes and high shipping insurance rates.

On the other side of the balance sheet, by mid-1813, all along the American East Coast, foreign trade was sharply reduced and customs revenues dried up. “Commerce is becoming very slack,” reported John Hollins of Baltimore on April 8, “no arrivals from abroad, & nothing going to sea but sharp [fast] vessels.” It was not just the foreign carrying trade that was affected, but coastal commerce between the states as well. The British blockade—the “Wooden Walls” placed off the US shore by the Royal Navy—was tightening its grip.

First instituted after war was declared, the British blockade of the US coastline was the classic strategy of the dominant sea power designed to prevent enemy warships and commerce raiders from going to sea and returning to port, and the wider economic blockade aimed at suppressing all trade. Plagued from start to finish by lack of resources to make it 100 percent effective, the blockade still had a great deal of success. Regardless of Admiral Warren's inadequate force, the blockade managed in 1812 to capture 240 American ships trying to slip out to sea, the vast majority of which were merchantmen engaged in normal commerce. In 1813, the blockade became more potent; squadron-size forces combining a 74-gun man-of-war with a frigate or more were off every major American harbor to keep the dreaded US Navy's frigates in port, or vulnerable to defeat in battle if they dared emerge from harbor. Small shallow draft vessels were also present to chase coasters and privateers, as well as American gunboats. The latter routinely attacked conventional Royal Navy ships operating in the restricted waters of bays and estuaries where they could not easily maneuver.

But mixed objectives by the Admiralty hindered the blockade's results. The focus on destroying American naval forces through the diversion of fleet resources to Chesapeake and Delaware Bays under Admiral George Cockburn, and the huge number of ships used in the effort to trap enemy warships in port, such as Decatur's squadron at New York, or the Chesapeake in Boston, left holes in the blockade that, militarily, more than offset the victories gained over American warships either defeated in combat or locked up in port.

During the opening months of 1814, the blockade seemed almost nonexistent since Warren had to leave much of the coast unguarded due to the Chesapeake Campaign, and continued chronic lack of ships. However, enough blockaders remained, allowing commercial interdiction that proved a great success. Unarmed merchants no longer ran the blockade, coastal trade had almost entirely ceased, and neutrals no longer legally entered American ports.

Spring saw an increase to 85 British warships available for duty in American waters as a result of the abdication of Napoleon in April. The new head of the North American Station, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, brought increased vigor, and more men and ships, to the blockade effort. Yet the flow of enemy warships and privateers continued from the southern ports, since the admiral concentrated his resources from the Chesapeake Bay northward to the previously unblockaded New England coast. The southern coast did not receive British attention until August 1814, when several squadrons were sent down there. By the end of 1814 there were 120 Royal Navy ships, including those at Jamaica, manning the blockade. In January 1815, the Royal Navy got serious when it seized Cumberland and St. Simons Islands and created a base for disrupting coastal trade traffic.

Although extremely costly to American trade during the last two war years, the British blockade, declared in four separate stages, remained less than fully efficient during the war due to the lack of adequate numbers of men and ships, divergent British objectives, the hazards of the sea, British commitments worldwide, and the aggressive American response to it in the form of privateers. However, with conflict in Europe finally ending in mid-1815, Great Britain prepared to devote massive naval assets to the American War, which would have included enough ships and manpower to completely strangle US ocean and coastal commerce if it had the chance to be applied.

The notice in Baltimore's Weekly Register in late 1813 was quite explicit in its offer of a $1,000 reward for the head of a “notorious incendiary and infamous scoundrel, and violator of all laws, human divine, the British admiral COCKBURN—or, five hundred dollars for each ear, on delivery.” The bounty was placed in retaliation for the raids through spring and summer that year conducted by the British under Cockburn, by that time the most hated man in America, charged with every perceived atrocity committed on the East Coast.

George Cockburn, born April 22, 1772, made Lieutenant in the Royal Navy at age 21, thereafter commanding a sloop-of-war, then frigates in the Mediterranean and West Indies. In 1812 he was named Vice Admiral and assigned to be second-in-command to Admiral Warren with the North American Station. Upon arrival in the American theater, he was ordered by Warren to conduct combined operations—a natural adjunct to the British blockade—in the Chesapeake Bay region, designed to destroy enemy supplies and privateer nests, as well as bringing political pressure to bear on the US government by attacking an area which was very pro-war but might change its tune if hit hard by the conflict.

Sir George Cockburn, the British naval commander who conducted a series of destructive raids along the East Coast of America.

This siege of the American coast was possible due to the neglect that the Jefferson and Madison administrations had given to coastal and harbor defense, which was for the most part left to ineffectual gunboats, and the difficulties of navigation that was hoped would keep enemy vessels out. On land, the situation was no better, there being few regular infantry, and fewer artillery units on hand to defend coastal towns. Untrained local militiamen were ultimately depended upon, but most of the time they fled in the face of even minor British incursions.

Supported by conventional warships and smaller vessels able to penetrate the inland waterways, plus 380 sailors and Royal Marines, Cockburn conducted a campaign of burning and looting communities of anything that might aid the American cause. Frenchtown, Maryland, on the Elk River was plundered on April 29; then Havre-de-Grace, Maryland, at the entrance of the Susquehanna River was burned, even though it had no strategic importance. The towns of Georgetown and Fredericktown were torched next on May 6, after a half hour skirmish between 80 militia and British Marines involving Congreve rockets fired into the village. While these exploits cost the defenders hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost property, the British suffered only a handful of wounded for their efforts.

Moving to Virginia, Cockburn attacked Carney Island, near Norfolk, on June 22 by amphibious assault with 1,300 marines and sailors. The attack was repulsed by American naval and military forces, with a loss to the British of 177 killed, wounded and missing. The British were more successful in taking Hampton, Virginia, on June 25, but the resultant assaults, murder and looting of American civilians created an outrage in both the US and Britain.

Intending to keep a strong permanent presence in the Chesapeake Bay region, in early August, Kent Island, Maryland, was occupied by the British and used as a staging area for attacks on Annapolis, Baltimore, Washington, DC and the eastern shore of Maryland. The punitive raids spread panic and fury throughout the area, and would continue in 1814, but no matter how destructive their results they ultimately proved a strategic distraction and a diversion of limited British resources needed to complete their military and economic blockade.

When it could not make America sue for peace in 1813, the British lost faith in the combination of blockade and pinprick inland raids to get its enemy to end the conflict. The British government then, with the prospect of massive reinforcements of troops from Europe due to the fall of Napoleon, changed strategic course and determined to go on the offensive. With its newfound military strength, it would launch concerted drives on the American national capital and Baltimore from the Chesapeake area, and advance into New York State from Canada. This new strategy, it was assumed, would either win the war outright, or at the very least gain Britain favorable terms when peace was finally arranged.