LIEUTENANT JAMES SCOTT, AIDE TO BRITISH REAR ADMIRAL GEORGE COCKBURN, noted in his post-war recollections that his boss had long “fixed an eye of particular interest upon Washington [and that] every measure he adopted was more or less remotely connected, conceived and carried into execution” with a view to capturing the American capital. Toward that end, on July 17, 1814 he wrote to London outlining his plan. He suggested a landing at Benedict, Maryland, followed by the rapid seizure of Washington, DC, and then taking Baltimore and Annapolis.

The British blueprint to conduct more vigorous offensive operations along the US Eastern seaboard had been in the works well before Cockburn formulated his scheme, or the war against Napoleon had ended in Europe. These proposals were merely accelerated after the French Emperor's first abdication in April 1814. Thousands of British regulars from the Duke of Wellington's Peninsular Army had been transported from Europe across the Atlantic to Canada during the spring and summer of that year in preparation for increased land and naval pressure on the Americans.

To ensure this goal, the Admiralty transferred command of the North American Station from Admiral Sir John B. Warren to the more offensive minded 56-year-old Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane. A captain by the end of the American Revolutionary War, from 1790 to 1813 he served as commander of individual warships and squadrons in the English Channel, the Mediterranean, Western Atlantic and West Indies before formally replacing Warren in April 1814. Like Cockburn, Cochrane was eager to capture the enemy capital and prophesied that the town could be “either destroyed or laid under contribution.” By mid-July, Cockburn's naval force operating in the Chesapeake Bay was enlarged by the appearance of additional men-of-war and a battalion of Royal Marines. News also arrived that Cochrane was sailing from Bermuda with thousands more British troops to join him.

British Royal Artillerymen clad in blue uniforms rather than the usual scarlet. Contemporary illustration by Charles Hamilton Smith.

While the British threat to America's coastline and capital grew, the Madison administration slowly recognized the danger. On July 1, 1814, President Madison suggested that a force of 3,000 armed men be placed between Washington and the Chesapeake Bay, 50 miles to the east, and that another 10,000 militiamen be put on alert in the District of Columbia and the neighboring states. Next day, to facilitate the President's order, the 10th Military District was formed, encompassing the 200-mile-long Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, the District of Columbia, and northern Virginia between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers. Brigadier-General William Winder was given command of this new military zone. That spring, Winder had been released from British custody after his capture at the battle of Stoney Creek the year before. His appointment, over the objection of Secretary of War Armstrong, was purely political since his uncle, Governor of Maryland, would provide the bulk of the military force to defend Washington. Winder's qualifications as a soldier were summed up by Lieutenant-Colonel William Duane, Army Inspector General's Department, when he wrote that Winder “knew no more of military matters than his horse, and I am satisfied that he could not put a company in motion after two years experience.”

Over the next six weeks, Winder made no moves to fortify his charge or concoct a plan for its defense. His inertia was aided by Armstrong's refusal to concede any threat to Washington. This conceit translated into not letting available militia take the field unless there was an imminent threat of an assault on the capital. To those who foresaw an enemy descent on Washington, Armstrong berated them by proclaiming, “But they certainly will not come here [Washington]. What the devil, will they do here? No! No! Baltimore is the place, Sir. That is of so much more consequence.”

The British strategic goal in the Chesapeake was based upon the premise of creating distractions that would aid British efforts on the Canadian front. The directive from the British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies stated that the troops with Cochrane's fleet were “not to engage in any extended operations at a distance from the coast,” nor try to occupy any place permanently. Tactically, the commanders on the spot elected to go with Cockburn's plan, composed of two parts: diversionary naval raids up the Potomac River and the Eastern Shore to draw defenders away from the capital, and a march on Washington.

With a view to masking their designs on the capital, the Royal Navy chased down the Row Galley squadron of American Commodore Joshua Barney, a Revolutionary War hero, whose flimsy sail and oared barges hovered in the Patuxent River (which flowed south and east into Chesapeake Bay), constituting the only American naval defense in the area. Conveniently, this preliminary operation brought the British within a day or two's march from Washington.

On August 18, Cochrane's fleet of 46 men-of-war and transports entered Patuxent River, disgorging men and material at the small river port town of Benedict, 25 miles up from its mouth. Next day, the British ground force commander, Major-General Robert Ross, organized his troops into three brigades, one each under Colonel William Thornton, and Lieutenant-Colonels Arthur Brooke and William Patterson. His force included the 4th, 44th, 21st and 85th Light Foot Regiments, as well as 600 Royal Marines, a contingent of sailors, three artillery pieces, and Congreve rockets—a total force of 4,500 men.

British Field Officer of the Royal Engineers.

Major-General Ross, born in Dublin in 1766, embarked on a military career with the British Army in 1789, rising to the rank of Colonel in 1808 after seeing service in Holland, Egypt and Spain. From 1812–14, he fought under Wellington in the Iberian Peninsula and was made Major-General. He was seriously wounded at the battle of Orthez. While recovering from his injuries, he was named commander of the expeditionary force assigned to Admiral Cochrane's fleet in the war against the United States. Courageous, cautious, deferential, a strict disciplinarian, and loved by his men, Ross was a soldier's soldier.

On August 20, Ross set out west on foot with Cockburn's small boats on the river paralleling the army's march. The target was Barney's little flotilla at Pig Point. Cockburn's marines and sailors reached there on August 22, only to see the 17 vessels of Barney's squadron blown up by the Americans. Barney's 400 flotilla men and five cannon then marched to join the gathering Washington defenders. That day, Ross' command reached Upper Marlboro, Maryland, less than 20 miles from Washington, after covering 39 miles from Benedict in sweltering summer heat, but against no opposition. By the 23rd, Admiral Cochrane, who was becoming uneasy about the distance between the fleet and Ross' army, ordered the General to return to Benedict; but Cockburn convinced Ross to continue on to Washington.

Meanwhile, Winder had since the 18th called on all available troops to muster at Wood Yard, 12 miles east of the District of Columbia; the militia from the Baltimore region were to rendezvous at Bladensburg, Maryland, ten miles east of the capital. On the 22nd, the 10th Military District commander concentrated his forces at Battalion Old Fields (modern Forestville, Maryland), eight miles from the British then laying at Upper Marlboro, and the same distance from Washington. On the morning of August 23, the British, leaving their marines behind, started the 12-mile trek to Bladensburg. In response, Winder pulled back to Washington from his Battalion Old Fields site.

At noon on the 24th, the red-clad column sighted US troops beyond Bladensburg. They were formed on the west bank of the Anacostia River to deny the 120-foot-long bridge over the waterway to the British. The American position to the east was bordered by the river's marshy bank. Low ground sloped slightly higher to the west. The Old Bladensburg-Georgetown Road, and the Washington Post Road met 75 yards west of the bridge to form a single avenue. One mile southwest of the bridge was a ravine crossed by Turncliff's Bridge. A 600-yard-long north to south ridge, cut by several gullies, was further west. The entire area was mostly open fields, offering little concealment, dissected by fences.

Defending the west side of the river, just across from Bladensburg, was Brigadier-General Tobias Stansbury's 11th Maryland Militia Brigade. By not occupying Bladensburg, he failed to avail his men of the trenches dug there by the Americans the week before. In addition to his infantry, he set up an artillery battery on the road covering the bridge. To the right of the guns were Pinkney's Rifle Battalion; to the left-rear were a few infantry militia companies. Behind this screen, he placed the 1st, 2nd and 5th Maryland Militia Regiments, with a battery and 380 dragoons to their left. Further back on the ridge, west of Turncliff's Bridge, Winder established a third line made up of Brigadier-General Walter Smith's 1st Columbian Brigade (DC militia), on the left of the Washington Post Road. Barney's seamen, some US Marines and five artillery pieces took station to the right of the DC militia astride the road, while militia from Annapolis held a small height on Barney's right. Stansbury had ordered the span over the river destroyed but that was not done. Furthermore, the second American line was spread out too widely to effectively support the first line.

At 1:00pm, Thornton's Light Brigade, having arrived at Bladensburg ahead of the rest of the British army, was given permission by Ross to attack. This was a risky decision, since in case of a setback the unit would be unsupported. Nevertheless, the 85th Regiment and one light company of the 4th Regiment charged through Bladensburg and over the bridge, six abreast. Sergeant David Brown, 21st Foot, recalled that “the bridge was crossed under a heavy fire of musketry and artillery, with tremendous effect for at the first discharge almost an entire company was swept down.” Captain James Knox of the 85th, seeing the casualties mounting from his outfit, felt that “by the time the action is over, the devil is in it if I am not either a walking major or a dead captain.” Regardless of the losses, the British kept crossing. As American militiaman Henry Fulford wrote, the Redcoats “took no notice of [their losses] … the instant a part of a platoon was cut down, it was filled up by the men in the rear.” Once on the west bank, and Pinckney's riflemen had been dispersed, the British light troops deployed in open order and rushed Stansbury's second line, only to be pushed back to the river by a counter-charge from the 1st and 2nd Maryland Regiments.

In response, Ross threw in his recently arrived 4th and 44th Regiments, ordering their brigade commander Arthur Brooke to threaten both enemy flanks after he crossed the river. He then rushed off to personally encourage the men of the 85th Regiment. Once the 4th crossed the water, they struck the American right, while the 44th did the same on the other flank. All the while the Marylanders of the second line were being pummeled by Congreve rocket fire. The new enemy push drove Ragan's regiment from the field and endangered both wings of the 5th Maryland Regiment, causing it, and the adjoining cavalry, to flee down the Washington Post Road in great disorder.

With the entire American defense line dissolving in retreat, the British shifted their assault straight down the road at the new anchor of the American line—Commodore Barney, his naval artillery, and some US Marines. But “Wellington's Invincibles” were halted, according to the Commodore, who ordered an 18-pounder to be fired “which completely cleared the road.” Barney's cannon barked twice more at the advancing enemy who were either killed or thrown back. Avoiding the sting of the American 18-pounders on the road, the British hit Barney's right flank, receiving two ragged volleys from the Maryland militia units guarding there, before the Americans fled before the point of British bayonets.

After just having his horse shot from under him, Ross ordered a thrust at Barney's left against Colonel George B. Magruder's nervous 1st DC Militia Regiment, scattering them. Seeing this, a panicky Winder directed the infantry supporting Barney's naval guns to fall a short way back. They did, but failed to stop until they were off the battlefield. Ross took advantage of this error and sent his infantry directly at the now exposed enemy artillery's right. As the British closed on the gun position, American navy and marine officers shouted to their men, “Board 'em, board 'em”—the only close quarter combat order they knew. As the position was overrun, Barney was wounded in the hip by a musket ball and captured, while his men spiked the guns and fought their way to safety. The other artillery unit fighting alongside Barney, Major George Peter's Battery, also escaped.

The battle of Bladensburg cost the ill-trained American army of 6–7,000 men, no more than 40 killed and 60 wounded, with 120 captured, along with ten artillery pieces. Ross lost 64 dead, 185 wounded, and 107 deserted or captured. It was a contest marked by poor generalship on both sides, each commander attacking piecemeal, risking defeat in detail.

By the 25th, the American fugitives from the battle had either gone home, like Smith's 1st Columbian Militia, or were rallying, like the remnants of Barney's boatmen and newly arriving Maryland and Virginia militia, at Rockville, Maryland. The British did not pursue the Americans for more than a mile after the fight—the 95-degree heat and the fatiguing pre-battle march prevented them from doing so. However, at 6:00pm, Ross and Cockburn, escorted by Patterson's men, marched to Washington, which was entered by the Admiral and General with a 200-man patrol at 9:00pm on the 24th. While near the Robert Sewell House, looking for someone to negotiate the surrender and ransom of the city, Ross' party was fired on, losing one killed and three wounded. Ross fell from his mortally injured steed, but was unhurt. Immediately, the building from which Ross' party received the shots was stormed, but the perpetrator got away. The house was then set on fire since it had been used for hostile purposes. Ross then proceeded to set up a bivouac on Capitol Hill.

British troops march into the American capital and set fire to it on August 24, 1814.

The city Ross and Cockburn entered had been largely abandoned by its population of 8,000, many of its citizens preferring to hide in the woods rather than remain in town under British occupation. Elbridge Gerry, Jr. sarcastically wrote to his wife from the capital, days after it was occupied by Ross, saying that many tried to leave the city on the enemy's approach “but were out run by the militia.” The days leading up to the battle of Bladensburg saw the evacuation of government documents to Leesburg, Virginia, while official records and legal tender went to Frederick, Maryland. Some war material from the Washington Navy Yard had also been removed. President Madison and a small party wandered about Rockville after Bladensburg, while Winder headed for Baltimore, and Armstrong arrived at Frederick.

Once in control of the American capital, Cockburn urged Ross to burn it to the ground in retaliation for the destruction of York in Upper Canada in 1813. Ross compromised by ordering the destruction of all the public buildings only. To Captain George Gleig, 85th Foot, a veteran of the Peninsular War, the resulting firestorm so impressed him that he wrote: “Except for the burning of St. Sebastian [in Spain], I do not recollect to have witnessed at any period of my life a scene more striking or sublime.” The US Senate and House of Representatives chambers in the Capitol Building were burned by Ross's Quartermaster General, Lieutenant George De Lacy Evans, and Lieutenant James Pratt of the Navy. A number of junior officers were outraged by the order—a Captain Smith writing later that “I had no objection to burn[ing] arsenals, dockyards etc, but we were horrified at the order to burn the elegant Houses of Parliament.” On the lower floor of the House, Cockburn found Madison's copy of the receipts and expenditures of the US Government for 1810. He kept it as a memento of his triumph. Soon the rising wind blew fiery embers onto the shingle roof of the Library of Congress, dooming that edifice.

Determined to obliterate the US Supreme Court building, British arsonists piled furniture on the main floor and set it alight, but the building's brick vaulting held firm and kept the fire at bay. As the flames spread through the city, Ross accepted lodgings in the house of Dr. James Ewell. Ross and Cockburn then took 100 soldiers and sailors to the White House. At 10:30pm, the intruders found that the staff had fled and that the main dining area had been prepared to serve 40 guests. Hungry and parched, Ross and his men helped themselves to the feast. He then had his Chief Engineer, Captain Thomas Blanchard, burn the structure down. As the interior of the President's home was consumed by fire, Cockburn removed from it a chair cushion as a souvenir. An eyewitness reported how the White House was quickly engulfed in flames: “The spectators stood in awful silence, the city was alight and the heavens reddened with the blaze.” Dr. Ewell also commented on the President's house burning, horrified by the flames that burst through the windows “and mounting far above its summits, with a noise like thunder, filled all the saddened night with gloom.” However, the great sandstone walls withstood the heat and remained standing. The brick US Treasury building on the east side of the White House was then burnt. To Mordecai Booth, a US Navy Department clerk, who saw the capital in flames from near the Washington Navy Yard, it was “A sight so repugnant … so dishonorable, so degrading to the American character, and at the same time so awful.”

Anticipating its capture, the Americans had destroyed the Washington Navy Yard, including the warships Essex and Argus. The sight moved Mary Hunter, a city resident, to comment: “You never saw a drawing room so brilliantly lighted as the whole city was that night. Few thought of going to bed—they spent the night gazing on the fires and lamenting the disgrace.”

At midnight, Cockburn, after prowling around the city, came across and wrecked the office of the National Intelligencer newspaper, and was only prevented from having it fired by the pleas of some locals fearing the proposed burning would spread to their homes. A late night rainfall dampened down most of the blazes set by the British and saved great parts of the town. Next day, amid the continuing flames and petty plundering by officers, as if to assuage their guilt, a British enlisted man was apprehended for looting and shot.

Washington's destruction continued on the 25th with Ross completing the demolition of the Navy Yard, the burning of the State and War Department offices, and the Long Bridge across the Potomac River. The US Patent office was spared. Not so the Green Leaf's Point Arsenal, which due to an accident blew sky high the buildings, ammunition and 75 British soldiers carrying out its destruction. Writing home, an officer who witnessed the catastrophe stated that the carnage at the arsenal was “a thousand times more distressing than the loss we met with in the field of Bladensburg.”

A severe thunderstorm touched down that day, uprooting trees and tearing off rooftops, adding to the fiery chaos on the ground. Men, horses, even cannon, were tossed about by strong winds. Finally at 8:00pm, fearing an American attack, Ross secretly led his men out of the capital to rejoin the balance of his force at Bladensburg while Washington continued to burn and glow in the dark as the British departed. One American in Washington at the time believed that Ross had reason to be worried, writing that, “At this moment a legion of troops [such] as Colonel H [Henry “Light Horse'] Lee, could have entered Washington and have routed Ross, Cockburn, and as many of the incendiaries, drunk on the night of the conflagration, as they pleased to select.” That evening the entire British army marched out of Bladensburg, arriving at Benedict on the 29th. Two days later, it embarked on Cochrane's ships.

The British public received the news of the sack of America's capital as an example of their army and navy's military prowess, and payback for American destructive acts to private property in Canada. For many US citizens, however, the events at Washington stirred national pride and increased their support for the war and the Madison administration. It also revealed the magnitude of the British threat to many who had previously felt the conflict was not their concern. What happened at Washington determined many to protect their communities.

As the British made their way out of the capital city, two last casualties of the campaign were identified. Secretary of War Armstrong, strongly blamed for the defeat at Bladensburg and subsequent capture of Washington, resigned his post on September 4, handing over the job to James Monroe. William Winder, equally excoriated for what many were calling the “Bladensburg Races”—after the way the American defenders fled the battle area in great numbers—went on leave after the troops in Baltimore refused to serve under him. He left the army in 1815.

As reprinted in the Niles Weekly Register of September 24, 1814, London newspapers in mid- year prophesied that the British troops currently pouring into North America would “in all probability” target Washington, Philadelphia or Baltimore, “but more particularly Baltimore.” This prosperous city—at the time the third largest in the United States—sat at the head of the Patapsco River in the northern reaches of the Chesapeake Bay and was most bothersome to the British war effort. Over 250 licensed privateers operated out of the town against British merchant shipping, and she was a hotbed of pro-war sentiment. The destruction of the large amounts of naval stores held there would not only hurt the American war effort, but would also bring in profits from prize money for her conquerors.

Admiral Cochrane and General Ross embraced the idea of attacking Baltimore, since their schedule demanded preparation for a descent on the Gulf of Mexico. Furthermore, activities by Cochrane's amphibious force closer to New York, rather than continuing in Chesapeake Bay, would better relieve the pressure on Canada demanded by his government. However, just as he did before the march on Washington, Ross was convinced by Cockburn that Baltimore must be assaulted, with both of them then persuading Cochrane to follow that course.

Baltimore was in a strong position to resist an enemy attack. The port city had wealth to finance an effective defense, and a strong leader in Samuel Smith to direct it. Smith, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, a militia general prior to the conflict of 1812, a merchant and US Congressman as well as a Maryland State Senator, had the prestige and wisdom to unite the city's populace and coordinate the town's protection. By early September he had fielded 15,000 militiamen, and strengthened Baltimore's defenses at Fort McHenry, on a peninsula that projected into the harbor.

Smith correctly believed the British attack would come from the east, landing near North Point, in conjunction with a naval thrust at Baltimore Harbor. He therefore constructed a defense line covering that area on Hampstead Hill, consisting of more than a mile-long stretch of earthworks and gun emplacements, anchored by Fort McHenry.

On September 11, Cochrane's fleet moved into the Patapsco River. Upon learning this, Smith ordered 55-year-old Revolutionary War veteran Brigadier-General John Stricker's 3,000-strong 3rd Maryland Militia Brigade to move seven miles east of Baltimore to the area on Long Log Lane, below Trappe Road. Here a blocking position was set up where the land was less than a mile wide, bordered on the north by Bread and Cheese Creek, and to the south by Bear Creek. In front of the American line, which ran along a tree-lined fence, were open fields with little cover, over which the enemy would have to advance. As the night progressed, more troops joined Stricker. As he developed his land position, hulks were sunk in Baltimore's harbor channel, with armed barges behind them acting as floating gun batteries. This prevented enemy ships from dashing into the port and delivering overwhelming firepower on the town or Fort McHenry.

The next day, three miles from Stricker's encampment, the British landed at North Point over 4,000 men and eight pieces of artillery. Information from three captured American scouts mentioned a force of 20,000 ready to defend Baltimore. To this, assuming the number represented untrained militia, Ross replied, “I don't care if it rains militia.” He was convinced that he had a clear road to his objective until he reached Hampstead Hill. Before the General left to join his advance guard, he was asked if he would be returning that evening for supper. Ross reputedly answered, “I'll set up tonight in Baltimore or in Hell.”

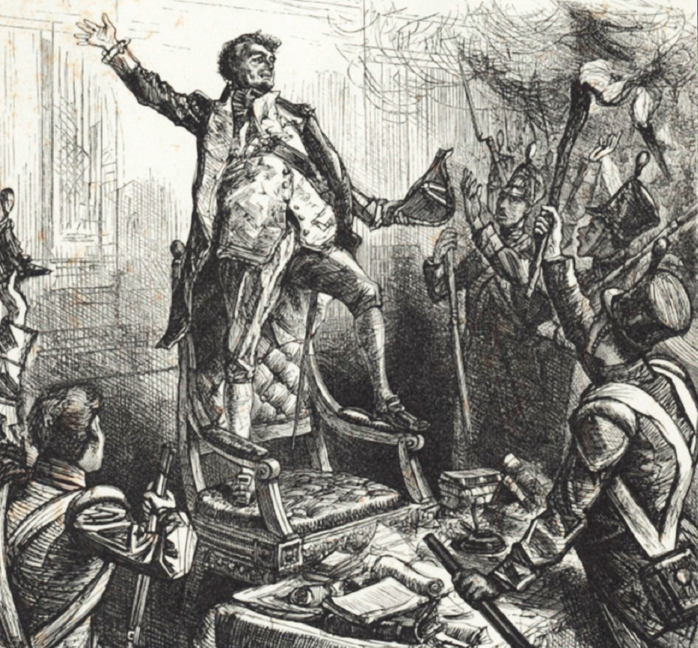

Rear-Admiral George Cockburn relishes his moment of victory by standing on the Speaker's Chair in the US House of Representatives.

The American defense at Long Log Lane was composed of the 5th Maryland Militia Regiment to the south of the road, its right connecting with some militia riflemen and cavalry, which extended the entire American right to Bear Creek; an artillery battery on the road itself; and the 27th Maryland Militia Regiment to the left of the road, placing its left flank on Bread and Cheese Creek. Stricker formed a second line 300 yards behind the first, with the 51st Maryland Regiment to the right and 39th Maryland Regiment to the left. A half a mile further back on Long Log Road was stationed the 6th Maryland Militia Regiment.

At 1:00pm, the British advance bumped into American pickets a half-mile from the American main line. A brisk skirmish ensued. Ross and Cockburn had been riding to the front when the firing began. Half an hour later, intending to bring up his main body, Ross turned in his saddle and said, “I'll bring up the column.” At that moment, he was struck through the right arm and right chest by a combination of buckshot and ball, falling from his mount mortally wounded and dying two hours later. It appears the General had been shot at by three militiamen picking peaches in front of the American line.

As Ross was carried to the rear, Colonel Arthur Brooke of the 44th moved to the front of the British column and took command—“an officer of decided personal courage but better calculated to lead a battalion, than guide an army.” He directed artillery to engage the enemy cannon, and placed his light troops to cover his entire front while an infantry line was formed. This was made up of a naval detachment positioned on the road just above Bear Creek; behind them was the 21st Foot, and then another Royal Marine contingent. To the right of the sailors and marines on the front line stood the 85th Light Foot, and to its right the 44th Foot. Around 2:30pm, Brooke sent his 4th Regiment by way of a concealed path to turn the American left flank. Stricker countered this move by moving parts of his 39th Regiment and two cannon to his left, followed by the 51st Regiment.

The British 4th reached its jump off position and charged, followed by the rest of the British line. The Maryland 51st panicked, as well as a battalion of the neighboring 39th Regiment, with both fleeing the field. But the remainder of Stricker's line held firm. Twenty yards from the American line, Brooke ordered his men to halt, fire a volley and then close with the bayonet. Lieutenant Glieg recalled that during this charge, “The Americans instantly opened a tremendous fire of grape upon us but reserved their musketry until we should get closer.” The opposing sides came together for a fierce ten-minute, close-quarter encounter, before the American line collapsed and retreated back to the position of the 6th Maryland Regiment a half-mile to the west.

Admiral Cockburn's aide, Lieutenant Scott, thought the enemy retreat was “a second edition of the Bladensburg Races.” Agreeing with Scott, Glieg concluded that “I never in my life saw a more complete rout. Horsemen, Infantry, Guns and all mixed together running like a flock of sheep, and our fellows knocking them over in dozens.” Regardless of those British officers' opinions, Stricker's men moved off the battlefield in relatively good order, and after forming line further west, were prepared to receive any following enemy. But Brooke did not pursue. He thought he was vastly outnumbered, and his men were worn out by the heat and the combat of the day. The fight, called the battle of North Point, cost the Americans 24 killed, 139 wounded and 50 captured. The British suffered 39 killed, including Ross, 251 wounded, and 50 missing.

On September 13, the British neared Hampstead Hill with its 11,000 defenders supported by 100 cannon. While an aborted attempt to turn the enemy line from the north by Brooke was going on, at 3:00pm Admiral Cochrane launched his attack on Fort McHenry, after which he planned to thrust into Baltimore Harbor and unhinge the fortified Hampstead line for the army. Half an hour later, three Royal Navy frigates, brigs, and tenders anchored five miles from the fort, while five bomb vessels—each capable of hurling 200 pound mortar shells at a rate of one every five minutes at 4,200 yards—and the rocket ship Erebus approached within two and a half miles.

Fort McHenry was commanded by Major George Armistead, a regular US Army officer. Under him 1,000 infantry and gunners manned the post with its 36 heavy cannon. The British opened fire on the fort out of range of the defenders' ordnance, which had a maximum range of 2,000 yards. Armistead later reported that even though he could not return fire since the enemy was out of range, and that “we were left exposed and thus inactive, not a man shrunk from the conflict.” As the enemy barrage rained down on the installation, one of the American 24-pounders was disabled, then a British shell crashed into the fort's main powder magazine—but fortunately proved to be a dud. Witnessing the intense bombardment of the fort, the Reverend John Baxley scribbled in his diary that “Such a terrible roar of cannon and mortars I never heard before.”

After eight solid hours of pounding the enemy position, and the American return fire slackening, Cochrane sent in three rocket vessels and the bomb ship to finish the job. They were met by heavy fire, pulled back out of range, and resumed firing. The shooting continued all night. A British landing party during the evening was put on shore to take the fort from the rear. Noticed by the defenders, it was driven back to their landing boats. At 7:00am on the 14th, after refusing to support Brooke's attack on Baltimore's land defenses—because he would have to bring his ships within range of Fort McHenry's guns—the Admiral halted the entire operation and recalled Brooke and his troops back to the fleet. Fort McHenry had been on the receiving end of 1,500 shells fired at it, 400 landing within the structure. The defenders lost four killed and 24 wounded.

It was at this time, too, that a civilian onlooker, Francis Scott Key, was so inspired to see the American fort withstanding the attack, that he composed a poem, later put to music, which became the US national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.”

After the British troops retreated from Baltimore with no enemy interference, they embarked on their transports on the 15th. For two days, the British fleet remained off North Point until it returned to the Patuxent River. Cochrane would not renew his assault on Baltimore since he had to prepare for a campaign in the Gulf of Mexico. His “invasion” of US territory at Baltimore had suffered a setback. And another such British effort, much further north, had already experienced a more serious defeat—one that would greatly contribute to the war's end.

The order, dated June 3, 1814, arrived that July marked “Secret” and was titled “Reinforcements allotted for North America and the operations contemplated for the employment of them.” It contained instructions from the British Government to Sir George Prevost, informing him that 10,000 British soldiers were being sent to Canada before the year's end to be used “to obtain, if possible ultimate security to His Majesty's possessions in North America.” It went on to give several suggestions for future operations. One that particularly stood out was the injunction that “Should there be any advance position on that part of our frontier which extends towards Lake Champlain, the occupation of which would materially tend to the security of the province, you will if you deem it expedient expel the Enemy from it, and occupy it.” With this directive in hand, and large numbers of reinforcements on their way, Prevost determined to strike at the enemy army at Plattsburg, New York, by land and water. After breaking the Americans there, he could winter on the edge of Lake Champlain—100 miles south of the Canadian border—and in the spring of 1815 threaten New York City. With peace talks about to start at Ghent, Belgium, a bold move such as this might end the war on British terms, and give Canada a new and more secure frontier.

Contemporary cartoon depicting King George III “In Mud to his Ears” in the War of 1812, caught between a Kentucky rifleman and a Louisiana Creole.

Putting his plan into effect, Prevost started to concentrate his army at Chambly, 20 miles south of Montreal, and 20 miles north of the American border. Of the 30,000 troops he would eventually command, he created a 9,700-man division of three infantry brigades as the initial spearhead for his invasion of the United States. His field force would also have his old Canadian Fencibles and Voltiguer units, 40 field guns, a number of siege pieces, 536 artillerymen, 172 Congreve rocketeers, and 340 dismounted troopers from the 19th Light Dragoons. Commanding his three infantry brigades were three Major-Generals chosen by the Duke of Wellington, all new to Canada. However, over them was placed the uninspiring Baron de Rottenburg.

Since the operation Prevost envisioned needed support from the navy to take control of Lake Champlain, and thus protect the army's supply route and flank, the Lake Champlain squadron was hurriedly strengthened. Its leader, Captain George Downie, led a force of brigs and sloops, 11 gunboats and HMS Confiance, a 37-gun frigate with long range 24 pounders—a third bigger than any American vessel, and the largest ship to sail on Lake Champlain up to that time. But all this took time, since the commander of all British naval forces on the Great Lakes, James Yeo, absorbed with operations on Lake Ontario, allotted little means to the Lake Champlain base at Isle-aux-Noix with which to build up its squadron. Furthermore, he and Prevost were not on good terms, which made military and naval cooperation on the lakes a dicey proposition throughout the entire war.

Opposing Prevost in the Champlain area was Major General George Izard, who by the end of August 1814 had 4,500 men at Chazy (12 miles north of Plattsburg) and Champlain, and another 600 working on fortifications at Plattsburg and Cumberland Head, just northeast of Plattsburg Bay. Situated on the west shore of Lake Champlain, Clinton County, New York, the town of Plattsburg was a natural gateway from Canada into the United States via the Richelieu River–Lake Champlain axis. During July, Izard concentrated his entire force around Chazy and Champlain under his second in command, Brigadier-General Macomb.

Alexander Macomb was a 32-year-old from Detroit, Michigan, but raised in New York City. A militia junior officer in the late 1790s, he entered the US Regular Army in 1801, becoming part of the elite Engineer Corps and rising to Colonel of the 3rd US Artillery Regiment by the eve of the War of 1812. After performing capably under Dearborn and Wilkinson during their campaigns of 1813, and the latter's early 1814 foray into Canada, he was promoted Brigadier-General. He briefly succeeded Wilkinson as commander of the Right Division at Plattsburg in early 1814. After Macomb was replaced there by Izard, he spent the entire summer drilling his brigade.

The impending British invasion by Prevost was such a well-kept secret that Izard was unaware of the menace through most of the summer. As a result, in July he asked the Secretary of War to be transferred to the Niagara Front, where active operations had been going on. His request was granted, but then learning of the enemy threat in early August he asked that he be allowed to remain at Plattsburg. Armstrong denied Izard's new motion, and the General left Plattsburg with 4,000 troops on August 27. Macomb was left in charge of the Plattsburg area with 3,000 US regulars and 1,500 militiamen.

“Everything is in a state of disorganization,” Macomb lamented in a letter after taking charge at Plattsburg, “works unfinished and a garrison of a few efficient men and a sick list of one thousand.” Things got worse when requests for the turnout of New York and Vermont militia moved at a glacial pace, if at all. Then, on August 31, a British infantry brigade crossed the border and camped on the north bank of the Great Chazy River—the rest of Prevost's army followed the next day. Macomb was urged by members of his staff to retreat to the south, but the General declined, determined to rely on his fortifications around Plattsburg, and he gathered his entire force to do just that.

The works Macomb planned to defend were three in number, and formed a straight line across the narrow peninsula that separated the Saranac River from Lake Champlain: Fort Brown stood just above the Saranac; Fort Moreau at the center of the peninsula; Fort Scott near the banks of Lake Champlain. Each was a large earthen emplacement fairly secure from the north, but more vulnerable from the south if they could be attacked from the rear. Two blockhouses, one covering the lower bridge over the Saranac, and the other where that river enters the lake, were also built and manned as outposts.

On September 1, Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough brought his squadron, with 820 men manning his ships, into Plattsburg Bay in preparation to meet the British naval force supporting Prevost's invasion. The young American naval officer was born in Delaware, joining the US Navy at age 17. After participating in the First Barbary War, he was made a lieutenant, then in October 1812 put in charge of the American Lake Champlain squadron, performing yeoman service throughout the war.

Macdonough picked Plattsburg Bay because the winds would be blowing against the British when they tried to enter it. Also, the confined space there would be to his advantage, due his superior number of short-range carronades. His ships had 35 carronades to Downie's 27, whereas the British had the advantage in longer-range pieces, 48 to the American's 35. Once in the bay, he formed his ships in line running northeast to southeast: the 20-gun brig Eagle at the north end, next the 26-gun Saratoga, then the 17-gun schooner Ticonderoga, and the seven-gun sloop Preble. Each ship had hawsers—cables—attached to its bow anchor and extending to the stern, and could be turned by hauling on the port or starboard hawser. Ten gunboats, with a total of 16 cannon, were placed in groups of two or three 40 yards west of the ships.

On September 4, the British army camped at the village of Chazy. Next day, the army moved toward Plattsburg in two parallel columns. On the 6th, the British right column passed East Beekmantown and engaged in a day-long skirmish with 700 New York militiamen supported by 250 regulars under Major John Wool, two artillery pieces and Macdonough's gunboats. In these brawls, the Redcoats lost 103 men, the Americans 45. Wool wrote long after the war about his rearguard actions against the British 3rd Foot Regiment along the Beekmantown Road. He recalled that though he was heavily outnumbered and hotly pressed, and his horse was shot from under him, his command “disputed every foot of ground until it arrived on the right bank of the Saranac in the village of Plattsburg.” He also claimed that he received no support from any militia until the close of the day. Regardless of Wool's successful rearguard actions, that same day Prevost's columns joined up and occupied Plattsburg, its 3,000 inhabitants having fled the borough. But he chose not to cross the Saranac River in the face of American forces on the south bank.

For the next several days, the British, while awaiting the arrival of their fleet, probed the bridges and fords over the river. They set up four artillery emplacements with the 16 heavy cannon, howitzers, and mortars that accompanied the army from Canada. The first salvos from theses were fired on the American works on the 11th. That day, Downie's squadron, with a total of 917 men, sailed from its base at Isle-aux-Noix, its final departure delayed due to the work that needed to be completed on HMS Confiance. With her sailed the 16-gun brig Linnet, the 11-gun sloops Chu and Finch, and 11 gunboats sporting guns.

On September 11, Downie sailed into Plattsburg Bay, hampered by the wind as he tacked northward into the bay. The battle, starting at 9:00am, quickly broke down into two segments: Eagle, Saratoga and seven gunboats against Confiance, Linnet and Chub at the north end of the line; Ticonderoga, Preble and three gunboats facing Finch and four gunboats—the other eight British gunboats never getting into battle. Fifteen minutes into the contest, Chub had her sails and rigging so damaged that she drifted out of control through the American line and surrendered. On the other end of the line, Finch was so badly hurt by Ticonderoga and Preble that she lost control and struck a reef on Grab Island and surrendered. Meanwhile, the American Preble ran aground, leaving Ticonderoga to finish the battle fighting four British gunboats, which repeatedly without success tried to board her.

On the opposite end of the American line, Eagle was pounded by Linnet and Confiance. Eagle then retired behind Saratoga, allowing the two British ships to devote their full attention to the latter. During this phase of the battle, Macdonough was wounded and the British commander, Downie, killed. Saratoga turned on her hawsers to bring her port guns to bear on Confiance. The British vessel attempted the same maneuver to bring her undamaged starboard side into action, but failed. As she tried to swing about, Asa Fitch, the purser on Saratoga, recalled how his ship fired her undamaged battery stuffed to the muzzles with handspikes at Confiance, with the result that, “Where it had been black with men the moment before, scarcely one man could now be seen.” Confiance, battered and unable to fire, surrendered at 11:00am. Twenty minutes later, after being pounded by Saratoga, the Linnet struck her colors. By this time most of the British gunboats had fled the scene.

U.S. Capitol after burning by the British. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

American cartoon accusing British of paying American Indians for scalps. This was not true and the British paid the Indians to bring in prisoners alive. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

On the day after the fight, Macdonough sent a message to Secretary of the Navy William Jones, stating, “The Almighty has been pleased to grant us a signal victory on Lake Champlain in the capture of one Frigate, one brig and two sloops of war of the enemy.” The battle cost the Americans 52 killed and 58 wounded; the British 54 dead, 116 injured. At day's end, both fleets lay shattered in the bay, not a sail of either functioning, and the Americans barely saving their main prizes, the floundering Confiance and Linnet.

It had been a fierce encounter, with HMS Confiance receiving 105 shots to her hull and almost sinking, while USS Saratoga sustained 55 hits. Julius Hubbell of Chazy remembered that “The firing was terrific, fairly shaking the ground, and so rapid that it seemed to be one continuous roar, intermingled with spiteful flashing from the mouths of the guns, and dense clouds of smoke soon hung over the two fleets.” After viewing the wrecked Confiance, he found her “absolutely torn to pieces” with mutilated bodies everywhere on her deck.

As the naval battle raged, Prevost ordered his 1st and 3rd Infantry Brigades of 4,000 men to assail the ford at Pike's Cantonment. After the British column became lost, they arrived at the crossing an hour later and rushed over the ford, dispersing 400 American militia guarding it, then waited for the rest of the army to pass to the south bank. While doing so, the British were under American artillery fire, with Captain James H Wood, Royal Artillery, being almost hit by a round shot that “stupefied me for some minutes and an inch or two closer would have made me shorter by the head.” At 3:00pm an order arrived, calling for a retreat from Plattsburg since the Royal Navy had lost control of Lake Champlain in that day's fight. Major-General Frederick P Robinson, in charge of the assault force, summed up the feelings of the entire British army after receiving the order to withdraw, saying, “Never was there anything like the disappointment expressed in every countenance. The advance was within shot, and full view of the Redoubts [the three American forts guarding Plattsburg area], and in one hour they must have been ours. We retired under two six-pounders posted on our side of the ford in as much silent discontent as was ever exhibited.”

Prevost's army hastily withdrew to the area around Montreal, closing down campaigning on the Lake Champlain Front for the rest of the war. His advance on Plattsburg was the first and last major offensive he conducted. Aside from the sacking of Washington, the only unqualified British achievement of 1814 was the easy occupation of the eastern third, including 100 miles of coastline, of Maine. That incursion was designed to serve as an all-British route from Quebec to Halifax. When peace was made, most of the area was returned to the United States.

Peace talks convened in August at Ghent, Belgium, with all eyes turned toward the US-Canadian frontier in anticipation of events there, which would determine the shape of the final settlement. The battle of Plattsburg vindicated that attention, but action in the Gulf Borderland also contributed its share in the making of peace.