IN THE FIRE OF “THE MILITIA WAS UP” AGAINST THE CREEKS, WROTE Andrew Jackson to Governor Willie Blount of Tennessee in June 1812. “They burn for revenge,” he continued, “and now is the time to give the Creeks the fatal blow.” Jackson's comments were in response to murders of whites earlier in the year by Creek Indians, whose confederacy spanned western Georgia and eastern Alabama. Those responsible were called “Red Sticks—from their practice of carrying wands painted red denoting war—and since 1811, encouraged by Tecumseh, were resisting the Americans. Many were Upper Creeks living in central Alabama, who rejected the white man's ways and his encroachment on Indian lands. In contrast, the Lower Creeks, residing in western Georgia and eastern Alabama, adopted white culture, extensively intermarried with whites, and made accommodations with the US government. By the spring of 1813, Creek depredations against whites were numerous, and the Creek nation was near civil war, pitting pro-white Lower Creeks against the Red Sticks.

The Americans believed that the British and Spanish furnished aid to the Creeks prior to the start of the War of 1812. The British did intend to support the Indians in the event of conflict with the United States, but did not take action to incite the Creeks to war before 1814. The Spanish favored an attack by the Indians on the US as the only way to defend Spain's weakly held East and West Florida; however, neither Spain nor Britain proved willing to fully supply the Creeks with arms until after their defeat at Horseshoe Bend in 1814. As a result, during the struggle between the United States and the Red Sticks, the latter could never supply and arm more than 2,500 fighters at any one time, with only one in three warriors possessing any type of firearm.

Seeking weapons and ammunition to carry on their fight with the pro-white Creeks, 300 Red Sticks, led by Peter McQueen, an influential half-breed among the tribe, visited the Spanish at Pensacola, Florida, in early summer 1813. They received powder and lead but no guns. On his way back to western Alabama, McQueen's party was attacked by180 undisciplined militia from the Mobile area under Colonel James Caller, who wanted to forestall an Indian war by capturing the munitions before they could be distributed.

Near Burnt Corn Creek, 80 miles north of Pensacola, on July 27, 1813, Caller's men attacked the Creek pack train and its dozen drivers. One hundred Creeks, who had crossed the water before the pack train approached, counterattacked, catching the militia by surprise, regaining their supplies, and scattering the Americans. This first fight between US military forces and Creeks during the War of 1812 claimed five dead and ten wounded Americans, versus two killed and five wounded Red Sticks.

Buoyed by his success at Burnt Corn Creek, and wishing to destroy a white settlement, McQueen targeted isolated Fort Mims on the east bank of the Alabama River, 35 miles north of Mobile in Mississippi Territory (the future states of Mississippi and Alabama). The fort, the strongest in the Territory, housed 553 whites, mixed bloods, friendly Indians and Negro slaves—all the types despised by the Red Sticks as representative of pro-white Creek society. Joining McQueen was William Weatherford, born in 1780, the child of a Scottish trader and a Creek woman, who was a Creek chieftain and wealthy planter. Weatherford, known as Red Eagle during the war, later claimed he was forced to join the Red Sticks since his family was being held hostage by them. He became the Creeks' most capable military leader.

Massacre of white settlers at Fort Mims by Creek Red Sticks warriors in August, 1813.

Portrait of a Creek chief in 1820s, son of a Scots father and native mother. Many mixed-blood warriors fought on both sides during the Creek War.

Defending Fort Mims was Major Daniel Beasely, a lawyer with little military experience, and 240 militiamen and armed settlers. This force would have been enough to protect the post, except Beasely took no defensive precautions to thwart an attack. At noon on August 30, 750 Creeks assaulted the fort while the garrison was at lunch. The Indians rushed the place, a few surging through the fort's open main gate, which could not be closed due to a sand mound that had accumulated against it. Beasely was killed as he tried to shut the jammed portal. Meanwhile, other Indians wrestled the fort's rifle loopholes from the control of the defenders, making a defense of the fort's walls impossible.

The defenders fought on inside the fort, but the Indians set it on fire and cut them down “like beeves in the slaughter pen of the butcher's.” Forty whites and mixed bloods escaped the inferno; 275 whites, mixed bloods and friendly Indians were either killed or taken captive. The murdered suffered awful deaths. Captain Kennedy, head of the burial party, reported that “Indians, negroes, white men, women, and children lay in one promiscuous mass.” All were scalped and the females of every age were butchered. He went on to record, “The main building was burned to ashes, which were filled with dead bones.” As the massacre took place, Weatherford claimed he had implored that the women and children be spared, but his pleas were ignored. The attackers lost over 200 killed and wounded.

After Fort Mims, the Red Sticks had no real plan of action other than Weatherford's strategy of creating a series of strongpoints throughout the Creek territory from which the warriors could strike the enemy as he approached.

The American reaction to Fort Mims called for the invasion of the Creek confederacy by four armies from different directions, combining at the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers, where they formed the Alabama River. During their march to the rendezvous point, the several columns were to engage Red Stick forces, burn enemy villages, destroy Indian crops, and build and garrison stockades the entire length of the routes of advance. The projected three-month campaign to subdue the Creeks turned into ten due to chronic shortage of supplies and the constant turnover of militia.

The first operations against the Red Sticks occurred along the Alabama River when General Ferdinand L. Claiborne, head of the Mississippi Territorial Militia, set out from Fort Stephens in western Alabama on October 12, 1813, to clear the area of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers. He went on with his 1,200 men to capture Weatherford's hometown of Holy Ground, containing 200 houses, on December 23. Less than 50 Indians under Weatherford opposed Claiborne, and after a sharp fight he retreated with a loss of 33 Red Sticks killed, while the Americans suffered one dead and 20 wounded.

Claiborne built a number of forts on the Alabama River, which cut communication between the Creeks and the Spanish at Pensacola, and cleared the lower part of the river of the enemy. In January 1814, he had to discharge his militia, and for the rest of the war the American troops on the Alabama River were too few to undertake anything but minor raids. But control of the Alabama made possible the transit of supplies, which sustained the operations of the main forces thrown at the Red Sticks, allowing them to remain in Creek country.

The force under Brigadier-General John Floyd moved west from Georgia to the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers to join with the army moving south from Tennessee under Andrew Jackson. Floyd's command of 1,500 men (including 400 friendly Indians) advanced 60 miles from the Chattahoochee River to the hostile town of Autosse, located on the south bank of the Tallapoosa River, 20 miles above its junction with the Coosa. On November 29, he formed his force into two columns: the right bordering Calabee Creek, while the left one surrounded Autosse and an adjacent village. Severe fighting erupted at dawn, the Indians being driven back to the woods behind the towns. Their lines were finally broken after Floyd bombarded Autosse with his artillery, followed by a bayonet charge. Both villages were burned, but most of the Red Sticks escaped after losing 200 killed and scores more wounded. The white army lost 11 killed and 54 wounded, including Floyd, and many allied Indians. Floyd wrote after the battle that so many Indian dead were found in heaps near the creek that the “river near the shore was crimson with their blood.”

French Pirate Jean Lafitte offers his services to Governor Claiborne (middle) and General Jackson (right) during the battle for New Orleans—and sub se quently received a pardon for his efforts providing men for its defense.

Floyd then retreated to the east shore of the Chattahoochee, his search and destroy mission completed, but hobbled by lack of provisions and the pending expiration of most of his militiamen's term of service. Floyd took the field again in mid-January, moving 41 miles west of the Chattahoochee where he erected Fort Hull. He had 1,100 militia and 600 natives under his command.

Hoping to defeat the invaders before Fort Hull was completed, the Red Sticks struck the American encampment at night on January 27, 1814. The camp was formed in two separate squares. Floyd recalled the Indian assault: “They stole upon the sentinels, fired upon them, and with great impetuosity rushed upon our line; in 20 minutes the action became general…. The enemy rushed within 30 yards of the [two pieces of] artillery.” The initial Indian onslaught drove the soldiers from part of their camp, and the severest part of the battle centered around the cannon.

Floyd lost 21 whites killed and 128 wounded, as well as five friendly Creeks killed and 15 wounded. The Red Stick total came to 49 killed and wounded. Although repulsed, the hostiles had badly mauled the Americans and carried out their most skillful attack of the war. In mid-February, Floyd took what remained of his militia back to Georgia, leaving Fort Hull garrisoned. It became a collection point for supplies intended for Jackson's army when it reached the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers.

As part of the concentration against the Creeks, General Andrew Jackson's 2,500-strong militia force left Tennessee for Ten Islands on the upper reaches of the Coosa River on October 25, 1813. Like the other American forces engaged against the Creeks, Jackson was chronically short of food. On November 2, he ordered Brigadier-General John Coffee's 900 Tennessee Volunteers and a party of allied Indians to attack the large Creek town of Tallasahatchee, 13 miles from present day Jacksonville, Alabama.

Coffee reached Tallasahatchee early next morning and placed his command, split into two columns, in a concealed circular formation around the town. The right column consisted of volunteer cavalrymen, the left of mounted riflemen. Two companies of horsemen were sent out in the open to draw out the enemy, who, seeing the exposed mounted detachment, rushed out to attack them. These retreated, pursued by the Creeks. After coming up to Coffee's hidden right, and receiving a strong volley of fire from the mounted troopers, the Red Sticks were halted in their tracks. The cavalry then charged, followed by the American lefthand column. Soon the Creeks were enclosed in a deadly circle and were slain as they fell back among the town's houses. Red Stick losses were 186 killed, with 84 women and children taken prisoner. Coffee lost five killed and 41 wounded. The town was demolished and the expedition rejoined Jackson's main force at its new base called Fort Strother near Ten Islands.

On November 7, Jackson heard that the friendly Creek village of Talladega, 30 miles from Fort Strother and defended by 160 warriors, was under siege by 1,100 Red Sticks. Gathering 1,200 infantry and 800 horsemen, Jackson made for Talladega. At 4:00am on the 8th, he formed three infantry columns abreast, with cavalry behind the left and right columns, and an advance guard of horsemen. The army took on a crescent shape with cavalry on the right and mounted infantry on the left wing. The object was to encircle the enemy once contact was made.

As at Tallasahatchee, a small American mounted advance element drew out the besieging Creeks, who attacked them, forcing the riders to retreat. The oncoming Red Sticks unnerved a militia brigade that started to crumble before them until mounted infantry from the reserve plugged the gap and repulsed the advancing enemy. The next 15 minutes witnessed continuous firing between the Red Sticks and the American infantry as Jackson's mounted wings closed the circle on the Creeks. Realizing the trap they were in, the Indians escaped through a hole in the American line, Jackson pursuing the fugitives a few miles. Over 290 Creeks were killed, while Jackson lost 15 killed and 85 wounded.

Lack of supplies prevented the US commander from continuing his offensive operations, and the next month saw his men, on the verge of starvation, demand release from service due to expired enlistment terms. A number of times the men started home to Tennessee until stopped by Jackson and his remaining loyal troops.

After much of his army disintegrated in December 1813, Jackson gathered a force of 800 infantry, 130 mounted men and 100 Indians. Raiding south of the Coosa River from Fort Strother, he beat the Red Sticks in two minor engagements at Emuckfau and Enitachopco. During February and March he organized a new army of 2,000 infantry, including the well-trained 39th US Infantry Regiment, 700 cavalry, 600 Indians and two pieces of artillery. On March 24, he set off from Ten Islands to attack a large Creek encampment on the Tallapoosa River.

Andrew Jackson's headquarters at the Macarty house.

At the Tallapoosa, 1,000 Creeks had constructed a breastwork across the neck of a bend in the river. The barrier—ranging five to eight feet high—had a double row of loopholes that allowed enfilade fire on any attacking force. Approaching his objective on the 27th, Jackson sent his mounted troops and most of his Indians, under Coffee, two miles below the Creek breastworks in order to surround the bend on the far bank and cut off any escape in that direction. During the battle, Coffee's men swam the river, took the Creek village, and laid down fire into the backs of the Red Sticks defending the breastwork against Jackson's main attack. The occupation of an island in the river opposite the western end of the Creek fortifications by Coffee deprived the Red Sticks of a place of refuge.

In the meantime, the American army was positioned in front of the Indian works, with the artillery 80 yards away from the nearest part of the enemy position. At 10:30am, the soldiers commenced a two-hour artillery bombardment that had little effect. Musket fire was also directed at the barrier when targets presented themselves.

Fearing that Coffee's isolated men would be overwhelmed, Jackson ordered a direct charge on the breastwork. The regulars and militia surged forward and a fierce fight ensued. Major Lemuel Montgomery, 39th US Regiment, joined by Lieutenant Sam Houston, future hero and president of Texas, mounted the top of the parapet. Montgomery was shot dead while Houston, hit in the thigh by an arrow, engaged the warriors in hand-to-hand combat. The Indians broke but continued to fight desperately, since their planned retreat across the river had been thwarted by Coffee's men. The battle then became a series of mopping up operations. One group of Red Sticks gained shelter under a bluff near the river. Houston stormed the position with a few others, receiving two more wounds for his trouble. Fire was used to flush the fugitives out and they were gunned down as they tried to escape the flames.

The battle of Tohopeka, better known as Horseshoe Bend, cost Jackson's army 26 killed and 106 wounded, most of them from the US 39th. Jackson's Cherokee allies lost 18 killed and 36 wounded, while his friendly Creeks sustained five dead and 11 wounded. Red Stick casualties were 557 killed at or near the barricade, while 300 more were shot down in the river trying to flee. This was attested to by militia officer Major Alexander McCulloch, who wrote: “The Tallapoosa might truly be called the River of Blood for the water was so stained that at 10 at night it was very perceptibly bloody, so much so it could not be used.” For all practical purposes, this battle ended the Creek War, as the remaining hostiles either surrendered or fled to Florida. William Weatherford gave himself up, and Jackson, out of respect for his opponent's bravery and ability, allowed him to go free. On August 9, 1814, Jackson signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson, concluding peace with the Creeks and forcing them to cede 23 million acres—half their homeland—to the United States and move further west.

“I hasten to communicate to you,” wrote Secretary of War James Monroe to Andrew Jackson on October 21, 1814, “the directions of the President, that you should at present take no measures which would involve this Government in a contest with Spain.” In other words, the Madison administration denied the General's requests during that October to allow him to capture the Spanish held city of Pensacola. But Jackson, as of May 28 the new commander of the Seventh Military District—encompassing Louisiana, Tennessee, the Mississippi Territory and West Florida—had no fear about a war with Spain if it meant US possession of Pensacola.

On August 22 Jackson moved his district headquarters to Mobile and, in complete disregard of his government's wishes, prepared to capture Pensacola, insisting that its capture was vital for the defense of Mobile and New Orleans against the British. Neglecting the defenses of New Orleans, “Old Hickory” led a 4,500-man army to Pensacola.

On November 7, 1814, Jackson camped his army on the west side of the town, facing the place's main defenses: Fort St. Michael, on a hill 400 yards from the town's west edge, supported by several blockhouses, and Fort Barrancas, located on the west shore near the entrance to Pensacola Bay. The Spanish garrison was made up of 500 infantry, some artillery, and an unknown number of British troops. Jackson determined to surprise them by attacking from the east.

To fix Spanish and British attention away from the real point of assault, Jackson sent 500 men to demonstrate against the town from the west. Meanwhile, at 9:00am, the General marched his main body in three columns on a circuitous route out of sight of Fort St. Michael to the east side of Pensacola, three miles distant. Once positioned, the Americans charged into the city: the column made up of regulars moving along Center Street; the men of the Tennessee volunteer force entering the street to their right; while the column made up of Choctaw warriors marched on the next street along the rear of the town in view of Fort St. Michael. Artillery attached to the attackers fell behind. The US regulars were met by three volleys of enemy artillery, and musket fire from a blockhouse and residences lining the street. Some cannon fire fell on the Americans from the British ships anchored in the bay. After a spirited charge by the Americans, all these obstacles were cleared, and a counterattack by Spanish troops from Fort St. Michael was easily repulsed. This was followed by the surrender of city. The entire action lasted less than half an hour.

Jackson's triumph cost seven killed and 11 wounded, in exchange for the deaths of 14 Spanish and six others hurt. Elated by the performance of his soldiers, he remarked to Governor Blount of Tennessee, “The steady firmness of my troops has drawn a just respect from our enemies.” On the 8th, as the Americans contemplated how to take Fort Barrancas, the British saved them the trouble by evacuating the 200-man Spanish garrison and blowing up the installation before sailing away. They relocated 150 miles to the east to the mouth of the Apalachicola River from which they continued to supply the Red Sticks and harass Georgia and West Florida for the rest of the war.

The capture of Pensacola was a significant triumph in the Gulf Coast Campaign. It deprived the British of a key base from which to conduct activities in the area, and reduced their options for future operations in the Gulf. This came on the heels of a failed naval bombardment and amphibious assault on American-held Fort Bowyer, an earth and log structure at the head of Mobile Bay, on September 15. After trading short-range gunfire for two hours with the 160-man garrison and its 11 medium cannon, the British four-ship squadron had a 20-gun vessel sunk and a brig badly damaged. A 250-man British Marine and Indian party, with one artillery piece, gained the rear of the fort, but after being fired on by the defenders promptly withdrew. This small but important action cost the British 32 killed and 37 wounded, while the defenders lost four dead and five wounded. After the repulse at Mobile, followed by the fall of Pensacola, Admiral Cochrane concentrated all his plans for the Gulf campaign on a direct attack on New Orleans.

After taking Pensacola and now focusing on the importance of Mobile, because it “will be able to protect the pass from New Orleans, and prevent the enemy from cutting off our supplies,” Jackson scattered his forces to forestall any threat to Mobile. One thousand horsemen were sent to the Apalachicola River to hunt down Redcoat detachments, Red Stick holdouts, and destroy this new enemy base. He strengthened the Mobile area, including Fort Bowyer, with three regular infantry regiments, and sent General John Coffee's 1,200 volunteer mounted riflemen to Baton Rouge. By the time Jackson reached New Orleans on December 2, the city was protected by only two under strength regular regiments and some militia.

Aerial view of battle of New Orleans showing British forces attacking the Line Jackson.

The British had been considering an attack on New Orleans before the War of 1812 commenced. “Where the Americans are most vulnerable,” wrote Admiral Cochrane in April of 1812, “is New Orleans and Virginia.” In a June 20, 1814 letter, he outlined a plan to take the city with the help of Indian allies, after securing a base of operations at Mobile.

New Orleans, the wealthiest population center in the United States, situated 105 miles upstream from the mouth of the Mississippi River, was vital to the economy of the states of the South and Midwest since it served as the main entry and exit point for commercial trade in that part of the country. The British motive for seizing the place was to use it as a bargaining counter in any peace negotiations.

From the start, the operation to take New Orleans went forward in piecemeal fashion, altered by events, such as the denial to the British of the use of Pensacola or Mobile as a logistical base. Cochrane reported, “The attack made by the Americans upon Pensacola has in a great measure retarded this service [the British Gulf offensive].” Also, the large participation of Indians the British counted on never came about due to the Red Stick defeat at Horseshoe Bend. What kept the plan alive was that throughout the US Seventh Military District during the latter part of 1814, there were only some 3,000 regular troops scattered about the entire region. Local militiamen were the only other forces near the Gulf Coast.

New Orleans was a difficult target. Above the mouth of the Mississippi River, it is located on dry land but surrounded by marshes, swamps, shallow lakes and the river itself. Except for a few trails and boat channels, the marshes and swamps were impassable. Of the seven practical routes that the British Army could have used to approach New Orleans, Jackson was convinced they would come up the Mississippi River, or through Lake Pontchartrain. He therefore strengthened his defenses at those points. As for the other approaches, lack of manpower, weapons, and time to fortify them made him rely on detachments of local militia to block those avenues by felling trees and establishing a series of coastal outposts. This was done well except that Major General Jacques de Villere, of the Louisiana militia, failed to completely plug those channels of Bayou Bienvenue which extended from Lake Borgne into the General's own plantation close to the city.

By mid-December, the American force in New Orleans was meager, just 1,000 regulars from the 7th and 44th US Infantry, a few artillery companies, and 2,000 militia. Nearby were General John Coffee's 1,600 riders at Baton Rouge. A further 5,200 Tennessee and Kentucky volunteers were also marching to the city but were weeks away. Naval forces for the defense of the town consisted of six gunboats, a 12-gun schooner and a 16-gun sloop, all under the command of Commodore Daniel Patterson. Although small arms were in short supply, the navy yard at New Orleans contained a large number of heavy cannon that would play a vital role in the coming fight for the city.

From Jamaica, Admiral Cochrane's fleet entered Lake Borgne on December 13, 1814. With him were 7,500 British soldiers and marines under the command of Major-General John Keane. Facing him were five gunboats, carrying a total of 45 cannon, under the command of Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones. Next day, since the Americans were in water too shallow for the British fighting ships to reach them, 1,200 sailors and marines in 42 boats and barges—each carrying a chaser gun at its bow—rowed up the lake against the current to engage the US squadron. It took 36 hours to catch the enemy, but after a spirited two-hour fight, all the US vessels were captured. The British then made their initial landings at Pea Island. On the 23rd, a landing was made in Bayou Bienvenue, a stream 20 miles east of New Orleans. Because the Mississippi delta prevented the British ships from proceeding up the river, the landing of troops and supplies had to be conducted by boats after a 70-mile row upstream.

The lack of enough shallow draft craft was a serious obstacle to British success at New Orleans, and placed a huge cost in time and manpower on the resupply effort. British Admiral Edward Codrington wrote about the problem, stating that “about 30 miles from where the frigates were, we assembled the whole army, but the labor of effecting this with our same means [the boats alone], and transporting the necessary ammunition and provisions, is beyond description.”

After disembarking at Bayou Bienvenue with 1,800 men, Keane opted to await reinforcements instead of attacking New Orleans. He set up camp at General Villere's plantation, eight miles from the city. After learning of the enemy presence at Villere's homestead, Jackson gathered 2,131 Tennesseans under Coffee, local militia and US regulars, with two six-pounders, to engage Keane. The gunboat Carolina set sail to support the American land attack. The rest of Jackson's command, perhaps 3,000 men, was detailed to guard the area between New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain, in case Keane's force was a diversion and the real enemy advance came through the Gentilly Road.

Under a full moon, the American army neared the British camp. It was then formed with the regulars on the right next to the river, artillery in the road, and Coffee's brigade with Colonel Thomas Hind's Mississippi Dragoons on the left. At 7:30pm, the Carolina moved past the British bivouac and fired her guns at the enemy campfires until 9:00pm. The Redcoats returned fire with three-pounder cannon and Congreve rockets. Neither side inflicted much damage on the other.

Andrew Jackson directs the action at the battle of New Orleans. Painting by H. Charles McBarron.

American artillery pound British soldiers. Jackson portrayed on the right.

When the American ship opened up on the British, Coffee's men charged the enemy right, over ground crossed by ditches and fences, hoping to outflank it. The British were pushed back 300 yards, and then the 85th Light Regiment ran into Coffee's men and were thrown back by their accurate fire. In their turn, Coffee's Tennesseans fell back after his opponent rallied a new line behind an old abandoned levee, and arriving British reinforcements began to curl around Coffee's left. Along the main road, Jackson's infantry and artillery drove back the British advance posts, manned by the 95th Rifles, until British resistance stiffened and thick ground fog made control of the American units impossible. Lieutenant Glieg, 85th Light Regiment, summed up the hard nature of the action when he reported that British officers and men in small groups “fought hand to hand, bayonet to bayonet, and sabre to sabre.” Captain John Cooke of the 43rd Light Regiment concurred with Glieg, saying that “since the invention of gunpowder, there is no instance of two opposing parties fighting so long muzzle to muzzle.” To the left of the road, US regulars of the 7th and 44th pressed the enemy back. In the American center, the force of the attack surprised the British. An anonymous Louisiana militiaman wrote “That they [the British] had no patrols, and appeared to be as happy and unconcerned as if encamped in Devonshire in England.” But the militia units failed to keep up with their comrades on either wing and eventually were ordered to halt.

General Jackson and his staff at the height of the battle. In the background, American troops capture a British standard.

During the fight the American artillery was almost captured, saved only after “Old Hickory” ordered parts of the US 7th Regiment to their rescue. Fighting stopped at 9:00pm, with the American army retreating two miles back behind the Rodriguez Canal. For Keane, the cost of the first battle for New Orleans was 46 killed, 167 wounded and 64 captured. Jackson's army lost 24 killed, 115 injured and 74 prisoners. Surprised by the boldness of his opponent, and surmising that Jackson would not have attacked if he did not have a sizable force, Keane remained in place until the rest of his 6,500 troops joined him. For his part, Jackson planned to continue the fight the next day until he realized that large numbers of British reinforcements were arriving. Neither commander knew that, a few hours after the night battle had ended, the American and British delegations meeting at Ghent had signed a peace treaty, concluding the War of 1812.

Keane's inaction following the fight of the 23rd granted Jackson a few additional days to strengthen his position at New Orleans, and to receive reinforcements. He started to improve his location on the canal, which soon became known as the “Line Jackson”—an earthen breastwork extending 600 yards from the Mississippi River across the plain and a further 200 yards into a swamp on the left. Vegetation and many of the buildings fronting it were cleared to create a good field of fire.

On Christmas Day 1814, the new commander of the British land forces arrived in camp. Thirty-two-year-old Edward Pakenham, an Irish-born aristocrat, joined the British Army in 1794, seeing service in the West Indies, where he was wounded, and in Holland. Fighting under his brother-in-law, the Duke of Wellington, in the Peninsular War, he commanded an infantry division and was made Major-General. Considered tactically astute, his bravery on the battlefield endeared him to his officers and men.

On December 28, Pakenham conducted a reconnaissance in force to the American lines using two brigade columns: the right under Major-General Samuel Gibbs, the left under Keane. If possible, he planned to develop it into a full-blown assault on Jackson's position. General Coffee's men stood on the American left where the defenses were far from complete, consisting merely of an abatis reinforced with heaps of earth. Gibbs made good progress, since there was no artillery on his front, and his approach, partially shielded by woods and some plantation buildings, allowed him to outflank the American line. Meanwhile, Keane's men, advancing near the river, joined by some friendly artillery, came under increasing enemy artillery fire from the American works, as well as from a US ship in the Mississippi. He soon put his men under cover in ditches.

Having completed his examination of the American position, and deciding not to attack, Pakenham ordered Keane and Gibbs to withdraw. His conclusion from the action was that Jackson's line could not be turned from its left. Of the decision to retreat when the flanking move was on the verge of success, a British participant at New Orleans (most likely Lieutenant Glieg) called the failure to flank the Americans “contemptible” and that “one spirited dart” would have enabled his comrades to carry the enemy works from “a horde of raw militiamen, ranged behind a mud wall.” British casualties for the day numbered 40 to 50 men while the defenders incurred nine killed and nine wounded.

After the British probe of December 28, Jackson accelerated the strengthening of his defenses. On his left he extended the original earthen palisade on the plain—which was at some points 20 feet thick at the base and five feet thick at the top—to the woods with a double rampart of logs, and cleared the ground to its front for 300 yards to provide a good field of fire. At the extreme end of this, he bent the line back to a right angle to provide further protection from a flanking maneuver. Twelve artillery pieces in seven batteries studded the length of his line from the left of the Mississippi, while a three-gun battery, increased to nine guns by January 8, was positioned on the right bank. Jackson also constructed a second defense manned by Louisiana militiamen a mile behind the first with a water-filled ditch in front.

On the foggy morning of January 1, 1815, Pakenham prepared to launch two infantry columns at the “Line Jackson” after his 17 heavy cannon had hopefully suppressed the enemy artillery and breached the American position. The British bombardment continued for three and a half hours against the American line on the left bank of the river, and for another hour against the battery on the right shore. Running low on ammunition, and not appreciably silencing the enemy cannon, Pakenham cancelled the planned infantry assault. Colonel Alexander Dickson, Pakenham's chief of artillery, blamed the ineffectual artillery fire on his “men being so unprotected [from enemy artillery fire], assisted in rendering the fire less active than it otherwise would [have been].”

Pakenham's final attempt to take the Line Jackson took place on January 8. The main attack was to be made on the British right by Gibbs' 2,500-strong 2nd Brigade column, covered by light troops. Soldiers would carry scaling ladders to mount the American parapet, while a contingent of troops would guard the storming force's flank. A secondary attack was to be made by Keane's 1,460-strong 3rd Brigade, with the special mission of capturing the American two-gun redoubt in front of the enemy right. The 1st Brigade, under newly arrived Major-General John Lambert, was placed in the center of the line as a reserve. The general direction of the attack was away from most of the American artillery and toward the left. As a prelude to the main attack, Colonel William Thornton's 780 strong 4th Brigade would cross to the right bank of the Mississippi the night before and take out American positions on that side of the river. He would then be joined by an artillery detachment, which would fire on Jackson's right across the river. Twenty-six pieces of heavy artillery would be available to aid the entire effort against 4,200 Yankee defenders.

Gibbs' men moved out at 4:00am but failed to take the ladders and fascines to fill in the American ditch with them. They had to return to retrieve the material and this cost the attackers a half hour of darkness. Worse, the storming parties with the ladders entered the action piecemeal as they raced to the head of Gibbs' column to plant their ladders against the enemy works, many failing to do this after coming under American fire. Thornton's crossing the river was also delayed, adding to the breakdown of Pakenham's plan. The British attack did not commence until 6:00am as dawn broke.

British 93rd Highlanders repulsed by US marines during battle of New Orleans. Painting by Charles Waterhouse.

The attempt to take the American redoubt was successful, but the British detachment could not break through the main American position. Meanwhile, Keane veered to his right to support Gibbs with the 93rd Highland Regiment, only to be wounded as the Highlanders “fell like pins in a bowling alley,” and, according to Lieutenant Charles Gordon, “after being subjected to a most destructive and murderous fire,” which eventually cost the unit 75 percent of its numbers. Gibbs' attack fell apart as his men, without the scaling ladders, desperately tried to claw their way up the parapet from the ditch in front of it. Most were rapidly shot down. Many took shelter in the trench below the mud walls. Above them, sheltered by their earth wall, were “Tennessee riflemen arrayed at the breastwork, the best marksmen in front,” according to Lieutenant John Fort, “and the two rear ranks loading and such a blaze of fire was perhaps never seen.” Concurring, another militiaman wrote that after the Redcoats managed to move into the ditch, “all the time the deadly rifles of the Americans poured in a steady stream of fire into the British ranks, which soon, riddled through and through, fell back in disorder from the foot of the parapet.”

After the signal for the advance was given, Pakenham rode to Gibbs' column. Seeing it stationary and some of the men retreating, he rode to the head of the formation and shouted at them: “For shame, recollect you are British soldiers, this is the road you ought to take.” He was persuading the men to move forward again when he was hit in the leg by American grapeshot, killing his horse. Remounted on another steed, he was cheering his troops on when he was struck by a cannon ball that shattered his spine. Around this time, Gibbs also received a fatal wound, and unable to bear the punishment inflicted on them, his 2nd Brigade broke and fled, shortly followed by their supporting artillery.

As their commander lay dying, the 2nd Brigade's light troops, under Lieutenant-Colonel Timothy Jones on the American left, pushed hard against Coffee's 1,200 marksmen, who were “protected by thick bushes, and dealt death from behind them to British platoons whose officers were falling fast but saw no enemy.” One such officer was Jones, mortally wounded before his men retreated.

Assuming command of the army after Pakenham's death, Major-General Lambert advanced his 1st Brigade 250 yards away from the American line in order to cover the retreat of the British attacking force and meet any enemy counterattack, which never came. One member of Lambert's Brigade, Sergeant John S Cooper, recalled that as his regiment advanced into position the American firepower was fierce and about “12 files from me on my right [a soldier] was smashed to pieces by a cannon ball.” An American soldier described the scene in front of the Line Jackson as one that resembled “a sea of blood,” referring to the red clad British dead and wounded that covered the battlefield. The time was 8:30am, an hour after the battle had begun, and the contest on the east bank of the river was over.

Blockaded in port for much of the war, USS Constitution defeated two British warships—HMS Cyane and Levant—in February 1815.

At the same time, 1,300 yards across the Mississippi River, Brigadier-General David B. Morgan and his 350 Louisiana State Militia were in trouble. Thornton and his British 4th Brigade had finally crossed the river and chased away the militia a mile below the US position. As the British neared Morgan's main defensive line, Thornton described it as “a very formidable redoubt, with the right flank secured by an entrenchment extending back to a thick wood.” But there was a gap in its center and the right was exposed, and these Thornton attacked. Kentucky militiamen had arrived to reinforce Morgan, but after a brief firefight they quickly decamped. Entering the main enemy position, the Redcoats capture 12 cannon. Thornton was badly wounded in the assault.

Jackson learned of the reverse to American arms and sent 400 reinforcements over the river to remove the enemy menace. While this was transpiring, Lambert ordered Thornton back to the left bank of the river. After an hour's combat, the battle was over, at a cost to the British of 291 killed, 1,262 wounded and 484 captured or missing. Jackson suffered 13 dead, 39 injured and 19 missing. The vast majority of the British losses were inflicted by American artillery and musket fire. Only 1,200 fabled Kentucky Long Rifles had been present in the fight, spread along Jackson's entire line. By the morning of the 19th, the British army had withdrawn from the battlefield. By the end of the month, they were on board Cochrane's ships sailing out of the Gulf. On February 12, 1815, 600 troops from Cochrane's fleet took Fort Bowyer in Mobile Bay in preparation to capture Mobile as a base in lieu of New Orleans. The next day, news finally reached the fleet that peace had been made between Great Britain and the United States of America.

“If we had either burnt Baltimore or held Plattsburg,” wrote Henry Goulburn, member of the British peace delegation meeting with their American counterparts in Ghent, Belgium, on October 21, 1814, “I believe we should have had peace on [our] terms.” But the British had not gained either place, and by late 1814 the thought of another costly campaign against the United States in the following year was something His Majesty's Government wished to avoid. For the Americans' part, their nation's inability to successfully carry the war to the enemy in Canada, even with the huge advantage in manpower she possessed, meant that only through a peace treaty could she extricate herself from a financially ruinous and humiliating conflict.

The final form of the peace agreement, which took shape in November 1814, made no mention of the maritime issues that had been the main cause of the conflict in 1812. Both parties would evacuate territories belonging to the other; prisoners were to be quickly exchanged; both would conclude peace accords with the Indians; and disputes over the US-Canadian border would be settled at a future date. The US Senate ratified the Treaty of Ghent on February 15, 1815, and it went into effect on February 17 at 11:00pm.

Of the reasons given for the final settlement, the most sound is that a process of attrition finally exposed the vital national interests both sides harbored. Since there was no single decisive military turning point, and the fundamental positions of the two countries were never that far apart, each was prepared to accept the status quo before the war.

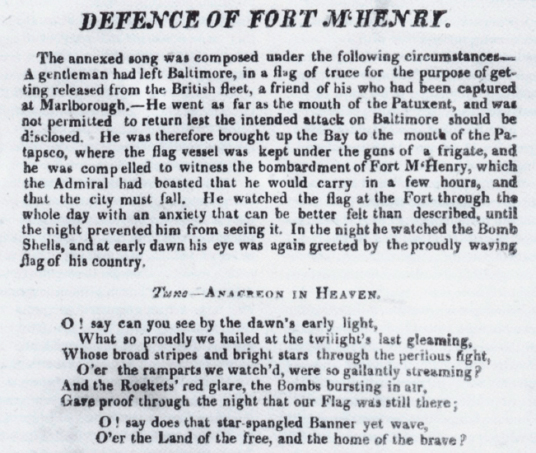

‘Home of the brave’— legacy of the War of 1812—extract from Francis Scott Key's lyrics to The Star Spangled Banner, recording the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814 and made the US National Anthem in 1931.