My goal was to keep tastes, character and traditions intact, bringing you the flavors of Emilia-Romagna in all their glory. Keeping recipes authentic and their tastes true brought the inevitable difficulties encountered whenever you take the regional food of one place to another part of the world. Often products are unavailable. For instance, the young, artisan-made balsamic vinegars used by families in Reggio and Modena for salads and for cooking into dishes (as opposed to the older, artisan-made vinegars used to flavor finished dishes) are not to be had in the United States. To come close to their rich yet acidic character, I borrow a trick from a talented Modenese cook. She adds a tiny amount of brown sugar to good quality commercially produced balsamic.

When I translated recipes from Emilia-Romagna to America, often products that seemed the same were not. For example, Emilia-Romagna’s salt pork is sweeter, rounder in flavor, and far less salty than the salt pork of the United States. And it is often cured to be eaten raw. It is not exported to the U.S.A. So here in America, I substitute domestically produced pancetta for salt pork. Its slow-cure and round sweet flavor comes close to the character of Emilia-Romagna’s salt pork.

As regional cooks now do, I use olive oil as the actual cooking medium, with reduced quantities of pancetta, prosciutto, and mortadella as flavorings. Although this changes some old recipes, with their generous quantities of pork and butter, it makes them available to a whole new public both in Emilia-Romagna and here.

In recipes where generous amounts of fat were called for, I recommend discarding it after browning or skimming it off after the final cooking, leaving behind only flavor. My thanks to Paula Wolfert and her work with fats for pointing out this technique. If dietary and health concerns require that you eliminate even small amounts of pork or butter, do not omit the dish from your repertoire. Substituting olive oil for all the fats will alter the dish’s character, but not its goodness.

Wherever I felt a dish’s authenticity and quality would be lost with these changes, I left it in its original state, just as it is preserved in Emilia-Romagna.

Cream is almost nonexistent in Emilia-Romagna’s dishes. Bolognese food expert Giancarlo Roversi said recently, “Whoever introduced cream into our cooking should be guillotined.” You will find cream in desserts, but rarely in savory foods.

It is very tempting to say that there is only one way to cook a dish. But the most important thing I learned in my years in Emilia-Romagna is one way of preparing a dish was always countered with varying renditions from down the block, down the road, or across the province. So what you will find in these pages are the dishes, and the methods of making them that are the most typical of Emilia-Romagna.

Vital to keeping tastes as authentic as possible is understanding the foundation ingredients of Emilia-Romagna’s foods, knowing what to seek out and how to use it. “A Guide to Ingredients” provides this information. Note that each recipe has a “Working Ahead” section, so you can anticipate the recipe’s rhythm. Menu suggestions are extensive. They illustrate not only how a dish fits into Emilia-Romagna’s cuisine but also how it translates into American dining.

Wine suggestions offer regional wines that may be available here. They also include wines from other parts of Italy, more readily found in the United States. While drinking a wine from the same origin as the dish is a wonderful experience, Emilia-Romagna’s wines are not broadly distributed in the United States at this time. Other Italian wines make fine stand-ins.

Since recipes tell only half the story of what makes this cuisine so special, I have accompanied many of them with notes that share the legends, histories, origins, and people that shape this place and its foods.

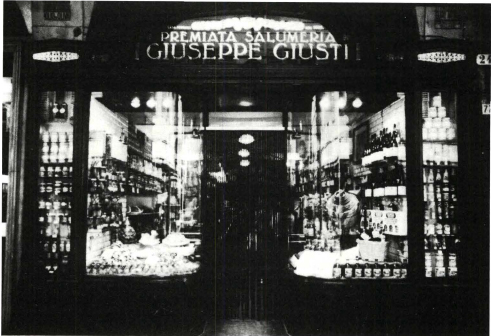

Giuseppe Giusti Salumeria, Modena