In Emilia-Romagna, where pasta reigns as queen, the ragù sauce is king. Although meat ragùs are made throughout Italy, I know of no other region where the sauce has gained such importance. Hardly a restaurant in Emilia-Romagna omits Tagliatelle with Ragù from its menu, and it is a rare home where some form of pasta sauced with some kind of ragù is not eaten at least once a week.

Ragù is a sauce of chopped meat(s) and sautéed vegetables cooked in liquid. The liquid can be stock, wine, water, tomato, milk or cream, or a combination of several of these. What a ragù is not is a tomato sauce with meat. It is a meat sauce sometimes flavored with tomato. In Emilia-Romagna and much of northern Italy, the meat is chopped into the sauce, while in southern Italy chunks of meat are frequently cooked into a ragù and served separately from it.

Such attention is lavished on ragùs in Emilia-Romagna, with each cook creating yet another interpretation, that their scope could never be reflected in only one recipe. I have gathered a diverse collection of favorites, each expressing another dimension of ragù or an important part of the sauce’s past. But was ragù always a sauce? Where did it begin and how did it evolve? Researchers in Bologna came to one conclusion, which, in turn, led me to another.

The most famous ragù in Emilia-Romagna is Ragù Bolognese. For the people of Bologna, their meat sauce is a vital part of their culinary identity. They believe Bologna is a center of discerning taste, where the best of raw materials are combined to perfection by gifted cooks.

When Bologna’s chapter of one of Italy’s preeminent gastronomic societies, L’Accademia Italiana della Cucina, chose one recipe as the most typical example of Ragù Bolognese, it raised a furor of debate. For weeks afterward, the city’s newspapers documented heated exchanges over the validity of the sauce. Almost everyone had an opinion. Home cooks questioned every ingredient, its quantity, its tradition, its inclusion or exclusion. Bolognese restaurant cooks, who saw themselves as the keepers of Bologna’s culinary traditions, were angered over not being consulted. Historians and food experts argued over the origins of the ragù, and its legitimacy as an expression of Bologna’s kitchen.

The Academy stood its ground. For them, the recipe found in Essential Sauces and Stocks embodied the most important characteristics of the ragù. It verified their belief that Ragù Bolognese began as a humble dish in Bologna’s farm kitchens a century ago.

According to Academy members, meat was expensive then, even for farmers. The beef in this sauce often came from a milk cow grown too old for milking. Skirt steak was a cut few people wanted because, in spite of its good flavor, it was lean and tough. Slow cooking tenderized the meat. The quantity of the sauce was stretched with generous amounts of vegetables and salt pork. Because the salt pork was the cheapest of meats and always available, often there was as much of it in the pot as beef.

The recipe’s reduced cream may appear an affectation, but in fact it nearly duplicates an original ingredient, cream skimmed from cooked milk. New milk, fresh from the cow, was preserved by long heating. Gradually the cream separated and coagulated on the milk’s surface. As the cooled milk stood by the kitchen door in a covered can, the cook would reach out with a shallow cup and skim off the top cream as it was needed.

That cream, full of flavor, went a long way in enriching the sauce and eliminating the need for large quantities of broth. Although made from bones and scraps, broth was still a meat product and treasured. Using cream created a sauce so rich and filling that only a little was needed for saucing enough tagliatelle to feed a large family.

With this explanation, the Academy’s Ragù Bolognese became official by decree. After receiving more government seals, ribbons and stamps than an international peace treaty, the recipe was deposited in the town hall to stand for all time as the typical ragù of Bologna.

My own research into the ragùs of Emilia-Romagna turned me in another direction. Much evidence points toward the oldest ancestors of today’s sauces being stews created in palaces, not on farms. I believe country-style ragùs came from working people emulating the sauces of the aristocracy. Since the mid-1800s ragù has been women’s food—the food of the home cook. But its birth could have been under the hands of men—the court cooks of the 16th and 17th centuries.

The region’s Renaissance cookbooks make no mention of ragù, nor of meat sauces for pasta. But they do give recipes for stews that sound like ragùs done in the fashion of the day, with an emphasis on spices and sugar. During the early 1500s, cookbook author Christofaro di Messisbugo served up ragù-like dishes to his master at Ferrara’s court banquets. Exotic, savory and sweet, these were chunky stews composed of cut-up meats. Sometimes fruits and nuts were added. Usually the stews were cooked in a strong broth and a tart or sweet wine. Seasonings seemed more Middle Eastern than Italian—rosewater, saffron, cinnamon, ginger, coriander, plenty of black pepper, and always sugar. These creations were eaten on their own or filled elaborate pies. They were not served over pasta, at least not yet. Through the 17th and 18th centuries the stews continued evolving. The quantities of sugar diminished and the spices were toned down.

Italy’s stews shared many characteristics with France’s ragoûts of the same period. (Ragoût was and is a stewlike dish of cut-up ingredients, cooked in liquid and eaten on its own. Italy’s ragù is always a sauce.) Considering the centuries of exchanges between the two countries, Italy’s stews and France’s ragoûts probably influenced each other. The important questions are: When did Italy’s stew become ragù? Did the name come from France? And when did Italian ragù first sauce pasta?

A combination of forces came into play toward the end of the 18th century that no doubt helped the word ragoût become ragù as it emigrated from France to Italy, and to Emilia-Romagna.

In the 1700s ragoûts became fashionable food for the well-to-do French, and contained everything from meats to vegetables to nuts and even olives. At the same time, Emilia-Romagna’s affluent citizens were captivated by all things French. The French were everywhere. Parma was annexed to the court of Louis XV, and 10 percent of her population was French. Modenese nobility took French husbands and wives. Each wedding brought large entourages of French relatives and servants. Bologna traded and politicked with France. Finally, Napoleon took possession of northern Italy for France in 1796. Why not bow to the fashion of the day and call those stews ragù?

The first record of someone doing just that was in the late 18th century when Alberto Alvisi, cook to the Cardinal of Imola, near Bologna, made a sauce called “ragù for maccheroni.” It tastes like a cross between classic Ragù Bolognese and a 20th-century French brown sauce. There were still remnants of those Renaissance flavorings. The sugar is gone, but the sauce’s flavors of deeply browned meat are set off by cinnamon and black pepper.

After 1830, ragùs appear frequently in Emilia and Romagna cookbooks. By 1832, Napoleon’s widow. Marie Louise, the Duchess of Parma, was dining on a ragù of chicken and prosciutto cooked in wine and lemon. Another ragù of chicken cooked with sausage, beef and giblets was saucing a Bolognese tortellini pie (see Pastas). Merchants and landowners in Romagna were eating a variety of ragùs on their own as well as over pastas, including one much like the giblet ragù in Ragùs. In mid-century, Romagna cookbook author Pellegrino Artusi was eating maccheroni with a ragù of veal filet in a Bolognese tavern while his companions plotted the unification of Italy. Interestingly, only a few of these ragùs contain tomato.

During the late 1800s, as white flour for pasta making became more affordable because of the Industrial Revolution, ragù crossed over class lines. The less affluent imitated the wealthy but used smaller portions of less expensive meats to make their ragù. Serving it over pasta stretched the sauce. An old saying states that tagliatelle with ragù becomes two courses in one: the pasta is the first and the ragù’s meat makes the second. Tagliatelle with ragù became a popular one-dish meal.

The recipes collected here are not historical curiosities. Each is a memorable dining experience in its own right. Ragù is still alive and well, and these recipes represent the best of the living tradition.

Building a Ragù

The following technique creates ragùs full of flavor, rich without being heavy. It can do the same for stews, braisings, and non-ragù sauces. Making a ragù involves three simple steps: browning the vegetables and meats, reducing flavorful liquids over the browned foods to build up layers of taste, then covering them with liquid and simmering gently until the flavors have blended and the meats are tender.

Browning: This is the taste foundation for the ragù. Browning slowly or quickly determines whether the foundation is mellow and sweet or robust and full-bodied. Slow browning over low heat brings out the sweetness of onion and carrot, while fast browning over high heat yields punchier, more robust flavors. Browning on medium heat strikes a balance between the two. I favor medium heat for most ragùs. Once the onion begins to color, the meats are added. After throwing off liquid, they begin browning. Some cooks like meats taken to a dark crisp brown, while others prefer lighter browning. Using a saucepan instead of a sauté pan ensures leisurely browning, building up rich caramelized flavors. As the foods cook, a brown glaze, packed with flavor, develops on the bottom of the pan. Protect it from burning by lowering the heat. Nonstick cookware discourages glazing and should not be used for ragùs, sauces, sautés, braisings, or stews.

Reductions: Repeatedly pouring wine, stock, and/or water over the browned base and simmering down each addition to an essence achieves two things: First, the reductions blend the highly flavored brown glaze into the sauce. Without it, ragùs lack depth. Second, each reduction builds another stratum of flavor, giving the sauce more complexity. Adding all the liquids at the same time produces a one-dimensional ragù. Wine creates a round and tangy taste layer, providing a needed contrast to the big flavors of browned vegetables and meat. Stock reduced to almost nothing imparts more full meat flavor. Repeat the stock reduction again and again, and see how intensely aromatic the sauce becomes. Always add any tomatoes after the reductions, as they will make the ragù acid-tasting.

Simmering: Flavors mellow and the ragù’s meats cook to tenderness when they are covered with liquid and left to bubble gently for an hour or more. Remove the sauce from the heat, let it settle a few moments, and then skim off all possible fat.

Ingredients

Beef: Often used by itself in Bologna, and blended with other meats in other parts of the region. The more flavorful the cut, the tastier the ragù. Best-tasting for ragù is the hanging tender, a small cut that literally hangs off the kidney inside the left hindquarter of the steer. Hanging tenders are not easy to come by (there is only one per steer) and must be ordered from a butcher. Skirt steak is my second choice. Cut from inside the rib cage in the forequarter, this, too, must be specially ordered and is worth seeking out. More readily available and almost as good are cuts from the chuck, such as blade-cut chuck, center-cut chuck, and seven-bone chuck steak or roast.

Capon Breast: Italy’s favorite domestic poultry gives the rich character to red meats and lightens ragùs. It is worth special ordering, but if unavailable, turkey breast comes close.

Chicken Giblets: Chicken or turkey giblets are frequently the mystery ingredients used with other meats in a ragù. Although almost impossible to detect, they impart body and character to the sauce. Ragùs composed only of giblets are often balanced with the addition of porcini mushrooms.

Pork: Cuts from the shoulder and sirloin are used in ragùs throughout Emilia-Romagna. Pork sweetens the sauce and balances particularly well in combination with veal.

Sausage: Often used in the ragùs of Modena, much of Romagna, and occasionally in Reggio, the sausage is never seasoned with hot pepper. Blending small quantities of sausage with other meats adds zest and character. A ragù of only sausage is traditional with gramigna pasta.

Veal: Usually blended with other meats for lightness. One exception is the Light Veal Ragù with Tomato, where the veal and tomato combination makes for a particularly fresh-tasting sauce. Seek out “kind” veal, from calves raised organically with space to move about.

Butter: Gives sweet, rich undertones.

Pancetta and Prosciutto: Their meat and fat are so suave that they give ragùs an elegance unequaled by butter or olive oil. Even when the fat is skimmed from the finished sauce, their flavors remain.

Lard: This has always been the cheapest and most accessible fat, used in the ragùs of the less affluent. Fine lard tastes of good pork meat. Cholesterol concerns have removed it from favor.

Olive Oil: Adds subtle fruitiness to ragùs. Traditionally Bologna and Romagna used more olive oil than the rest of Emilia-Romagna. Today, health concerns are causing its popularity to spread rapidly.

Wine: Wine’s roundness and acidity bring balance to full-bodied ragùs. Always add it after the meat has browned, and slowly cook the wine away to nothing. Do not use cooking wine. Instead, cook with a wine you would drink, using either red or white—the choice is up to the cook. Red Sangiovese di Romagna and white Trebbiano are most favored in Emilia-Romagna.

Stock/Broth: Heightens meatiness. Since reductions intensify the stock’s flavor, make sure it is saltless and, ideally, homemade.

Water: Used for clear, neutral flavor, letting other ingredients shine.

Milk: For an especially mellow and sweet sauce with tender meats, use milk as the main cooking liquid, adding it after the reductions. For more subtle sweetness, add milk in small quantities during cooking. Skim milk does an admirable job.

Porcini Mushrooms: Dried mushrooms used in small quantities give a wild, woodsy flavor to a ragù. For greater intensity, include their soaking liquid in the reductions. Do not overdo; porcini can easily dominate a sauce.

Herbs and Spices: Used infrequently in ragùs and always with a careful hand.

A Little History

The Cardinal’s Ragù is one of the earliest of Emilia-Romagna’s ragùs to be served with pasta. The recipe was found in a small manuscript of fifty or so written by Alberto Alvisi. Between 1785 and 1800 Alvisi cooked for the Cardinal of Imola, Gregorio Chiaramonti. The cardinal went on to become Pope Pio VII, while Alvisi dropped into obscurity. Food historians Aureliano Bassani and Giancarlo Roversi discovered his manuscript in Bologna’s archives, and published it 180 years after the cardinal dined on this ragù.

Ragù per li Maccheroni Appasticciati

[Makes enough sauce for 1 recipe fresh pasta or 1 pound dried pasta]

2 tablespoons fat rendered from salt pork

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 medium onion, minced

1¼ pounds beef skirt steak or boneless chuck blade steak, trimmed of fat and cut into ¼-inch dice

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

41/3 cups Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

2 tablespoons all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

Method Working Ahead: The ragù holds well, covered, in the refrigerator 2 days and freezes 1 month. Skim off the fat and reheat before serving. Taste for cinnamon and pepper before tossing with the pasta. There should be a sparkle of pepper and a soft backtaste of cinnamon.

Browning the Ragù Base: Heat the pork fat and butter in a heavy 4-quart saucepan over medium-high heat. Stir in the onions and meat, turning the heat up to high. Use a wooden spatula to push apart the pieces of meat as they throw off moisture and begin to brown. Lower the heat if the meat threatens to burn, or if the brown glaze on the bottom of the pan turns very dark. Cook until the beef browns.

Reducing and Simmering: Sprinkle the ¼ teaspoon cinnamon and a little salt and pepper over the meat, and stir in ½ cup of the stock. Scrape up the brown glaze with a wooden spatula as the stock bubbles slowly over medium heat. Once the stock has cooked down to nothing, add another ½ cup of stock. Repeat the reduction once more, using another ½ cup. Blend in the flour. Then pour in the remaining stock and bring it to a very slow bubble. Partially cover the pot and cook 2½ hours, or until the meat is tender. The sauce should have the consistency of heavy cream. Add water if it thickens too much or threatens to stick and burn.

Finishing and Serving: Sprinkle the sauce with generous pinches of cinnamon and pepper. There should be a whisper of discernible cinnamon and a gentle tingle from the pepper. Serve over garganelli, tagliatelle, dried boxed pappardelle, or baked with maccheroni as described in His Eminence’s Baked Penne.

Suggestions Wine: From Emilia-Romagna, a red Barbera or Merlot from Colli Bolognesi; or Piedmont’s Dolcetto d’Alba, or a Merlot from Friuli. All are sometimes available here.

Menu: Serve as a main dish after Fresh Pears with Parmigiano-Reggiano and Balsamic Vinegar. Ugo Falavigna’s Apple Cream Tart makes a fine finish. If you are offering the ragù as a first course, begin with the pears, serve the ragù, and then have Christmas Capon, Pan-Roasted Quail, or Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel. For dessert, have Frozen Zuppa Inglese from early 19th-century Parma.

Cook’s Notes The original recipe offered the cook a choice of beef, veal shoulder, pork loin, or poultry giblets. Any of these could be substituted in equal amounts for the beef. Adding Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese overwhelms the sauce’s cinnamon and pepper, and its texture alters the ragù’s silkiness.

A Remarkable Thigh

Chunks of boned chicken thigh are an important aspect of Baroque Ragù. They became part of the recipe one day when veal was not to be had. They stayed in the dish because of their succulence and absence of fat. Thigh meat loses none of its moist goodness through long sautés and simmerings. When excellent veal is not available for stews or braisings, substitute chicken thigh. Yes, its taste is different, but it unfailingly complements the flavorings and ingredients usually cooked with veal.

Ragù de’ Nobili

[Makes enough sauce for 1 recipe fresh pasta or 1 pound dried pasta]

1½ tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

½ medium carrot, minced

½ medium stalk celery, minced

½ medium onion, minced

2 ounces pancetta, minced

4 ounces mild Italian sausage (made without fennel)

12 ounces chicken thighs, skinned, boned, and cut into ¼- to ½-inch dice

4 ounces turkey or chicken giblets, trimmed and finely chopped, or 4 ounces lean ground pork

4 ounces lean beef chuck, finely chopped

1 California bay laurel leaf

½ cup dry white wine

Generous pinch of ground cloves

1¼ cups Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

1 clove garlic, crushed

1½ tablespoons imported Italian tomato paste

¼ cup heavy cream

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Method Working Ahead: The ragù can be refrigerated, covered, up to 3 days, and frozen up to 1 month. Skim any fat from the sauce before using. If you freeze it, add the cream when reheating.

Browning the Ragù Base: Mincing the meats by hand makes for better browning and gives a silkier texture to the sauce. In a 12-inch sauté pan, heat the oil and butter over medium heat. Add the vegetables and pancetta. Leisurely sauté, stirring often, until they begin to color, about 8 minutes. Add the sausage, chicken, giblets, beef, and bay leaf. Cook over high heat 8 more minutes, or until they begin to brown. Lower the heat to medium, and continue sautéing, stirring often with a wooden spatula, 10 minutes, or until the meat is rich dark brown. It should sizzle quietly in the pan, not violently pop and sputter. Slow browning protects the brown glaze forming on the bottom of the pan.

Simmering and Finishing: Drain off fat by tipping the browned meat into a large sieve and shaking it. Put the meat back into the pan, placing it over medium-high heat. Add the wine and cloves. Cook at a lively bubble 3 minutes, or until the wine has evaporated. As the wine bubbles, use a wooden spatula to scrape up the brown glaze from the bottom of the pan. Reduce the heat to medium and add ¼ cup of the stock. Take about 3 minutes to cook it down to nothing. Stir in the garlic, tomato paste, and another ¼ cup of stock; bubble it down to nothing again. Turn the mixture into a 2½- to 3-quart saucepan.

Add the remaining stock to the saucepan and let it bubble slowly, uncovered, 30 to 45 minutes, or until the stock has reduced by about one third and the sauce is moist but not loose. Add the cream, and simmer 3 to 5 minutes. Season to taste. Allow the ragù to cool; cover and refrigerate. Defat the ragù when it is cold.

Serving: Toss the reheated ragù with cooked pasta as suggested above. Serve in heated bowls, passing freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese separately.

Suggestions Wine: A soft red like a Sangiovese di Romagna Riserva, a young Merlot from the Veneto region’s Pramaggiore or Colli Berici, Tuscany’s young Chianti Montalbano, or Chianti Classico. Or accent the delicacy of the sauce with a big white Gavi dei Gavi of the Piedmont.

Menu: Serve the ragù over tagliatelle or pappardelle as a main dish after an antipasto of Hot Caramelized Pears with Prosciutto or Spring Salad with Hazelnuts. Follow the pasta with a green salad and then Caramelized Almond Tart or Strawberries in Red Wine. Offer it in small portions as a first course before Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit or Pan-Roasted Quail. Have Nonna’s Jam Tart for dessert.

Cook’s Notes The Ragù in a Pie: This ragù is vital to An Unusual Tortellini Pie. Double the ragù recipe, cooking the sauce in a 3½- to 4-quart pot instead of the 2½- to 3-quart size mentioned above. Browning the meats will take a little longer, but a 12-inch skillet still works best.

Ragù with Polenta: For an excellent main dish, spoon a single recipe of the ragù over hot Creamy Polenta.

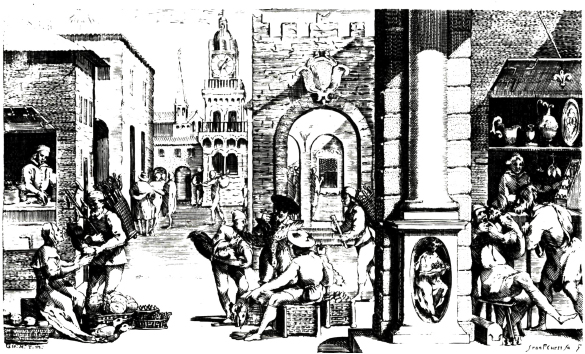

In Bologna’s marketplace, engraving by Giovanni M. Tamburini, from a picture by Francesco Curti, circa 1640

Casa di Risparmio, Bologna

Ragù Bolognese

For our modern tastes this ragù is reserved for times of special indulgence because of its generous amounts of fat. Although a fine lower-fat version follows, I urge you to sample this recipe, if only in very small portions to experience what home cooking was like a hundred years ago in northern Italy’s countryside.

[Makes enough sauce for 1½ recipes fresh pasta

or 1½ pounds dried pasta]

½ cup heavy cream

10 ounces fresh unsalted fatback or lean salt pork, cut into small dice

About 1 quart water

1 cup diced carrot (1/8- to ¼-inch dice)

2/3 cup diced celery (same dimensions)

½ cup diced onion (same dimensions)

1¼ pounds beef skirt steak or boneless chuck blade roast, coarsely ground

½ cup dry Italian white wine, preferably Trebbiano or Albana

2 tablespoons double or triple-concentrated imported Italian tomato paste, diluted in 10 tablespoons Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

1 cup whole milk

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Method Working Ahead: The ragù is best kept warm and eaten within about 30 minutes after it has finished cooking.

Cooking the Cream: Simmer the cream in a tiny saucepan until reduced by one-third. There should be about 6 tablespoons. Set aside.

Blanching the Salt Pork: Fresh fatback needs no blanching. If you are using salt pork, bring the water to boiling, add the salt pork, and cook for 3 minutes. Drain and pat dry.

Browning the Ragù Base: Sauté the salt pork or fatback in a 3- to 4-quart heavy saucepan over medium-low heat. Sauté 8 minutes, or until almost all its fat is rendered. Stir in the chopped vegetables. Sauté for 3 minutes over medium-low heat, or until the onion is translucent. Raise the heat to medium and stir in the beef. Brown 5 minutes, or until the meat is medium brown in color and almost, but not quite, crisp. Take care not to let the meat become overly brown or hard.

Simmering and Serving: Stir in the wine and diluted tomato paste, and reduce the heat to very low. It is critical that the mixture reduce as slowly as possible. Cook, partially covered, 2 hours. From time to time stir in a tablespoon or so of the milk. By the end of 2 hours, all the milk should be used up and the ragù should be only slightly liquid. Stir in the reduced cream. Toss the hot ragù with freshly cooked tagliatelle and serve.

Suggestions Wine: A young red Sangue di Giuda from Lombardy’s Oltrepo Pavese area, the Piedmont’s “La Monella” from Braida di Giacomo Bologna, a light-bodied Merlot from the Veneto, or a young Valpolicella Classico.

Menu: Serve ragù and pasta as a main dish after a light antipasto of wedges of fresh fennel for dipping into tiny bowls of balsamic vinegar, or small portions of Spring Salad with Hazelnuts. For dessert, arrange apples, pears, and grapes on a platter, along with handfuls of unshelled nuts. Tucking clusters of glossy lemon leaves, fresh bay laurel, or evergreens around the fruit and nuts makes an appealing presentation.

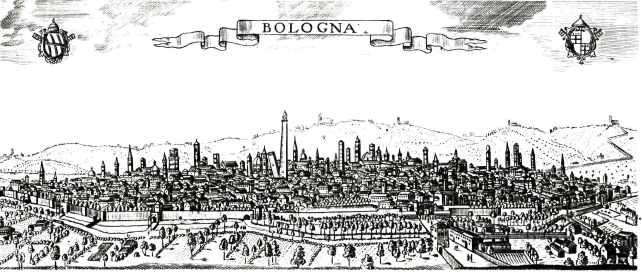

Old engraving of Bologna

A Lighter Contemporary Ragù

Bolognese

[Makes enough sauce for 1 recipe fresh pasta

or 1 pound dried pasta]

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 ounce pancetta, finely chopped

1 large carrot, finely chopped

2 small stalks celery, finely chopped

½ medium onion, finely chopped

1¼ pound beef skirt steak, or boneless chuck blade roast, coarsely ground

½ cup dry white Trebbiano or Albana wine

2 tablespoons double- or triple-concentrated Italian tomato paste, diluted with 10 tablespoons Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

1½ cups milk

Method Working Ahead: This ragù is at its best eaten within 24 hours after it is cooked. Cover and refrigerate it. Skim off the fat before reheating. The sauce can be frozen up to 1 month.

Browning the Ragù Base: Heat the oil and pancetta in a 3- to 4-quart saucepan over medium-low heat. Cook 8 minutes, or until the pancetta has rendered much of its fat but has not browned. Raise the heat to medium, stir in the chopped vegetables, and sauté 3 minutes, or until the onion is translucent. Keeping the heat at medium, add the beef. Cook, stirring frequently, 5 to 7 minutes, or until the meat is medium brown and almost, but not quite, crisp. Take care not to let the meat become overly brown or hard.

Simmering and Finishing: Add the wine and the diluted tomato paste. Stir to combine. Keep the heat very low. It is critical that the mixture reduce as slowly as possible. Cook, partially covered, 2 hours. From time to time stir in 2 tablespoons of the milk. By the end of 2 hours all the milk should be absorbed and the ragù the consistency of a thick soup.

Serving: Toss the hot ragù with freshly cooked tagliatelle, garganelli, or dried boxed casareccia or sedani maccheroni. Pass freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

Suggestions Wine: In keeping with its rural origins, wine for the ragù should be simple and direct: a young red Sangiovese di Romagna or from Umbria, a Barbera of the Bolognese hills (Colli Bolognesi) or a Piemontese Barbera.

Menu: Serve the ragù and pasta in small portions before Balsamic Roast Chicken, Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary, or Porcini Veal Chops. For lighter dining, have the ragù as a main dish after a few slices of coppa as antipasto. Make dessert Baked Pears with Fresh Grape Syrup.

Bologna’s marketplace, engraving by Giovanni M. Tamburini, from a picture by Francesco Curti, circa 1640

Casa di Risparmio, Bologna

Ragù alla Contadina

[Makes enough sauce for 1 recipe fresh pasta

or 1 pound dried pasta]

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 ounces pancetta, finely chopped

1 medium onion, minced

1 medium stalk celery with leaves, minced

1 small carrot, minced

4 ounces boneless veal shoulder or round

4 ounces boneless pork loin, trimmed of fat, or 4 ounces mild Italian sausage (made without fennel)

8 ounces beef skirt steak, hanging tender, or boneless chuck blade or chuck center cut (in order of preference)

1 ounces thinly sliced Prosciutto di Parma

2/3 cup dry red wine

1½ cups Poultry/Meat Stock, or 2/3 cup Meat Essences, or 1½ cups Quick Stock (in order of preference)

2 cups milk

3 canned plum tomatoes, drained

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Method Working Ahead: The ragù can be made 3 days ahead. Cover and refrigerate. It also freezes well for up to 1 month. Skim the fat from the ragù before using it.

Browning the Ragù Base: Heat the olive oil in a 12-inch skillet over medium-high heat. (Have a 4- to 5-quart saucepan handy to use once browning is completed.) Add the pancetta and minced vegetables and sauté, stirring frequently with a wooden spatula, 10 minutes, or until the onions barely begin to color. Coarsely grind all the meats together, including the prosciutto, in a food processor or meat grinder. Stir into the pan and slowly brown over medium heat. First the meats will give off liquid and turn dull gray, but as the liquid evaporates, browning will begin. Stir often, scooping under the meats with the wooden spatula. Protect the brown glaze forming on the bottom of the pan by turning the heat down. Cook 15 minutes, or until the meats are a deep brown. Turn the contents of the skillet into a strainer and shake out the fat. Turn them into the 4- to 5-quart saucepan and set over medium heat.

Reducing and Simmering: Add the wine to the skillet, lowering the heat so the sauce bubbles quietly. Stir occasionally until the wine has reduced by half, about 3 minutes. Scrape up the brown glaze as the wine bubbles. Then pour the reduced wine into the saucepan and set the skillet aside.

If you are using stock, stir ½ cup into the saucepan and let it bubble slowly, 10 minutes, or until totally evaporated. Repeat with another ½ cup stock. Stir in the last ½ cup stock along with the milk. (If using Meat Essences, add it and the milk to the browned meats, and do not boil it off.) Adjust heat so the liquid bubbles very slowly. Partially cover the pot, and cook 1 hour. Stir frequently to check for sticking.

Add the tomatoes, crushing them as they go into the pot. Cook, uncovered, at a very slow bubble another 45 minutes, or until the sauce resembles a thick, meaty stew. Season with salt and pepper.

Serving: Toss with freshly cooked pasta and serve immediately. Pass freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

Suggestions Wine: A red Bresciano Chiaretto from Lombardy’s Riviera del Garda, Sicily’s Cerasuolo di Vittoria, or Apulia’s velvety, full Salice Salentino Rosso.

Menu: Offer as a main dish after Fresh Pears with Parmigiano-Reggiano and Balsamic Vinegar. Follow with Salad of Mixed Greens and Fennel, and Home-Style Jam Cake. Serve in small quantities as a first course before Balsamic Roast Chicken, Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, or a lighter dish of Grilled Winter Endives. End the meal with Meringues of the Dark Lake and espresso.

Ragù degli Appennini

[Makes enough sauce for 1½ recipes fresh pasta

or 1½ pounds dried pasta]

2½ to 3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 medium onion, minced

1 small carrot, minced

2 pounds boneless venison, hare, wild boar, wild rabbit, elk, or beef, trimmed of excess fat and cut into ¼- to ½-inch cubes

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

1 large clove garlic, crushed

2½- to 3-inch sprig fresh rosemary, or 1 teaspoon dried whole rosemary leaves

3 large leaves fresh sage, or 3 large dried sage leaves

1 tablespoon imported Italian tomato paste

¼ teaspoon ground cloves

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

3 to 4 tablespoons wine vinegar

1 cup dry red wine, Barolo or California Zinfandel

2 cups Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

Method Working Ahead: The ragù holds well in the refrigerator 4 days and freezes up to 1 month. Remove any hardened fat from its surface before serving or freezing.

Browning the Ragù Base: Heat the olive oil in a 12-inch sauté pan over medium-high heat, and add the onion and carrot. Turn the heat down to medium, and cook 3 minutes, or until the onion is slightly softened but not browned. Add the meat to the pan so the pieces do not touch, and sprinkle lightly with salt and pepper. Take about 20 minutes to brown the meat on all sides, turning the pieces with a wooden spatula. Adjust the heat so as not to blacken the brown glaze forming on the bottom of the pan, and to protect the onion and carrot from burning. A leisurely browning builds up deep brown flavors.

Adding the Seasonings and Reducing: Once the meat has reached a rich dark brown color, sprinkle it with the garlic and herbs, and cook another few seconds. Stir in the tomato paste, cloves, cinnamon, and vinegar. Cook 1 minute, still over medium heat. Add ½ cup of the red wine and simmer, uncovered, over medium heat, 5 minutes, or until all the liquid has evaporated. As the wine cooks down, scrape up the brown bits on the pan’s bottom with a wooden spatula. Turn into a 4-quart saucepan, and add the rest of the wine. Concentrate the sauce’s flavor base even more by simmering it 10 minutes, or until all the liquid has cooked off. Stir frequently.

Simmering the Sauce: Add the stock, partially cover the pot, and lower the heat so it cooks with an occasional bubble. Cook, stirring now and then, 1½ to 2 hours, adding water or stock as needed to keep the meat barely covered with liquid. The cooking time varies according to the meat being used. It should be tender but not falling apart, generously moistened but not soupy. If necessary, uncover and simmer off some of the liquid. Aim for deep, robust flavors, with a suggestion of the vinegar’s tang. Add a teaspoon of vinegar if needed. Season with salt and pepper.

Serving: Defat the sauce. Toss with freshly cooked pasta and serve immediately. Pass freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

Suggestions Wine: Romagna’s Barbarossa di Bertinoro, Sangiovese di Romagna Riserva, or Bologna’s Barbera dei Colli Bolognesi di Monte San Pietro. From other parts of Italy: Tuscany’s Rosso di Montalcino (Brunello of young vines), Carmignano, or Chianti Classico. When cooked with strong game like hare, an aged Barbaresco or Barolo from the Piedmont.

Menu: Serve as a one-dish meal followed by a Salad of Mixed Greens and Fennel and chunks of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese for a savory finish.

In the tradition of feast days and special occasions, serve over pappardelle in small portions before Pan-Roasted Quail, Balsamic Roast Chicken, or Christmas Capon.

Cook’s Notes Game Cuts: The best game cuts to use here would be shoulder, rump, shank, neck, or leg.

Polenta Variation: Cook Polenta and pour it onto a heated platter. Spoon hot ragù over the polenta, and serve accompanied by freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

Grilled Polenta Variation: Slice cooled or leftover Polenta about ½ inch thick. Brush lightly with olive oil on both sides, and grill in a ribbed skillet or in a heavy frying pan until golden brown on both sides (the polenta is especially good cooked over a wood or real-wood-charcoal fire). Arrange on a heated platter and spoon the simmering ragù over the slices.

Ragù Vecchio Molinetto

[Makes enough sauce for 1 recipe fresh pasta

or 1 pound dried pasta]

4 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 medium carrot, finely chopped

1 large stalk celery, finely chopped

1 medium onion, finely chopped

1 pound boneless veal sirloin or shoulder, trimmed of fat and connective tissue, diced into ¼-inch pieces

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

2-inch sprig fresh rosemary, or ½ teaspoon dried whole rosemary leaves

½ cup dry white wine

2 teaspoons imported Italian tomato paste

1 cup water

1½ pounds canned tomatoes with their juice or full-flavored fresh tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped

Method Working Ahead: The ragù’s flavors are best the same day it is cooked. But it can be partially cooked 1 day ahead, with the tomatoes added the day it is served. Take care in reheating. If the veal overcooks, the flavors will flatten.

Browning the Ragù Base: Heat the oil over medium heat in a heavy 3½- to 4-quart saucepan. Drop in the carrot, celery, and onion. Sauté 10 minutes over medium to medium-low heat, or until the onion is very soft and beginning to color. Turn the heat to medium-high and add the meat. Stir the veal with a wooden spatula, scooping under it to keep the meat from sticking. Allow 8 to 10 minutes for the veal’s liquid to evaporate, then adjust the heat so that it is cooking slowly, taking about 20 minutes to reach deep golden brown. Stir frequently. Sprinkle the meat lightly with salt and a few grindings of pepper. Add the rosemary sprig, cook another 5 minutes, then discard it.

Reducing: Stir in the wine. Let it bubble down to nothing while you scrape up the brown glaze from the bottom of the pan. This takes 3 to 4 minutes. Blend in the tomato paste and water. Bring the ragù to a slow bubble over low heat.

Simmering: Partially cover and cook 1 to 1¼ hours, or until the meat is tender and the sauce is richly flavored. The consistency should be thick but still moist. If necessary, add a little more water during cooking. (If you are preparing the sauce ahead, stop at this point and allow it to cool; then cover and refrigerate. One of the keys to its fresh flavor is cooking the tomatoes only a short time.)

Finishing and Serving: Stir in the tomatoes and cook slowly, uncovered, 5 to 10 minutes. The meat and tomato flavors will blend, but the tomato must retain its fresh, distinctive character. Toss the ragù with fresh or boxed tagliatelle. As befits a sauce from Parma, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese is delicious with the ragù.

Suggestions Wine: A young red Merlot del Piave of the Veneto, a Sangiovese di Umbria, or a red Rincione of Sicily.

Menu: Serve in small quantities before Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken (also from Il Vecchio Molinetto), Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, or any other dish made without tomato. Serve as a main dish, beginning the meal with Salad of Tart Greens with Prosciutto and Warm Balsamic Dressing. Ugo Falavigna’s Apple Cream Tart from Parma is an ideal finale.

“Stretching the Pot”

“Stretching the pot” is a phrase I often heard from the Tuscan side of my family. This expression came to life for me years ago in the mountains above Reggio and Modena. After talking with a farmer about his crops, I was invited to join his family and friends for dinner. A sauce very similar to Game Ragù had been made to dress pasta. With the arrival of five unexpected guests, stock and water were blended into the ragù. After about 20 minutes of simmering it appeared on the table as a filling and satisfying soup, with plenty for all.

Try adding 2 quarts of stock to this sauce (after refrigerating and defatting). Serve with a bowl of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese for sprinkling over the soup and either Modena Mountain Bread or Spianata.

Ragù di Rigaglie di Pollo

One of my favorite ragùs, this sauce has an ancient lineage, dating back at least 400 years. Giblets are the last thing most of us expect to taste like a blend of well-aged beef, fine old Barolo wine, and mature prosciutto. But they do, and this sauce is one of the most distinctive I know. Its character is full-blown and robust, yet elegant and perfectly balanced on the palate. There are several interpretations within Emilia-Romagna and many more in neighboring regions, where it is sometimes called “false game sauce.” Tagliatelle bring out the ragù’s elegant side, while small hollow macaroni like penne or sedani emphasize its earthiness.

[Makes enough sauce for 1 recipe fresh pasta

or 1 pound dried pasta]

¼ cup (¼ ounce) crumbled dried porcini mushrooms

1 cup hot water

4 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 ounces lean pancetta, finely chopped

1 large onion, minced

1 small carrot, minced

1 small stalk celery, minced

2 pounds chicken or turkey hearts and gizzards, trimmed of tough tissue and cut into ¼-inch dice

2 tablespoons minced Italian parsley

1 large clove garlic, crushed

1 large California bay laurel leaf

2 large fresh sage leaves, or 2 whole dried sage leaves

1½ cups dry white wine

2 tablespoons imported Italian tomato paste

3 cups Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock (68)

1 cup drained canned tomatoes, crushed

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Method Working Ahead: The ragù can be made up to 4 days before serving. Store it, covered, in the refrigerator. It freezes successfully 1 month. Remove any hardened fat from its surface before freezing or reheating.

Preparing the Porcini: Stir the mushroom pieces into a bowl of cold water, let the particles settle, and lift out the mushrooms. Repeat with fresh water until there is no sign of grit or debris. Soak the rinsed mushrooms in the hot water while the meat is browning. Line a small sieve with a paper towel to strain the liquid.

Browning the Ragù Base: Heat the oil in a heavy 6-quart pot over medium-low heat. Add the pancetta and minced vegetables. Stir them occasionally as they cook, about 8 minutes, or until the onions are soft and clear. Raising the heat to medium-high, sauté the vegetables another 5 minutes, or until they begin to color. Turn the heat down to medium or medium-low, and add the gizzards and hearts. Brown them very slowly, taking 30 to 40 minutes. Use a wooden spatula to scoop under the meat and turn it, keeping it from sticking.

Reducing: Lift the mushrooms out of their liquid, reserving the liquid. Stir the mushrooms, parsley, garlic, bay leaf, and sage into the pot. Sauté 2 to 3 minutes over medium-low heat. Strain the mushroom liquid into the pot. Let it bubble slowly over medium-low, about 5 minutes, scraping up the brown bits clinging to the bottom of the pan. Cook until the liquid has evaporated. Blend in the wine and tomato paste. Keeping the wine at a slow bubble, reduce it to nothing. Repeat the process with 1 cup of the stock. Stir in the remaining 2 cups of stock and tomatoes. Bring to a very slow bubble.

Simmering: Partially cover the pot. Cook 1 hour, or until the gizzards are tender and the sauce is thick but not dry. Add water or more stock if necessary. Season with salt and pepper. Let the sauce cool a short while off the heat sauce, then skim off the fat.

Serving: Bring the sauce to a simmer, toss with freshly cooked pasta, and serve accompanied by freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

Suggestions Wine: A red Barbera from the region or from the Piedmont, a Sangiovese di Romagna Riserva, or a lighter-styled Barolo from the Piedmont.

Menu: Have small portions of the ragù over penne before Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken, Grilled Beef with Balsamic Glaze, or Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary. Serve as a main dish after Hot Caramelized Pears with Prosciutto. Finish with Strawberries in Red Wine.

Cook’s Notes Risotto Variation: Follow the recipe for the Classic White Risotto, adding a half recipe of Giblet Ragù once the rice is sautéed. Reduce the stock in the risotto by 2 to 3 cups. Proceed with the recipe as directed.

Ragù di Carne e Marsala

[Makes enough sauce for ¾ recipe fresh pasta

or 12 ounces dried pasta]

12 ounces turkey or chicken giblets, trimmed of tough membrane and cut into large chunks

8 ounces veal loin chop, boned and cut into large chunks

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 small to medium onion, minced

½ stalk celery, minced

½ medium carrot, minced

1 ounce Prosciutto di Parma, minced

3 ounces lean ground beef chuck

2 ounces prosciutto cotto or boiled ham, chopped

6 tablespoons dry Marsala

2/3 cup dry white wine

2/3 cup strained porcini mushroom soaking liquid (see Note)

1½ tablespoons imported Italian tomato paste

2/3 cup Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

Method Working Ahead: The ragù can be made up to 3 days ahead. Store, covered, in the refrigerator. It freezes well up to 1 month. Skim off any fat from the surface before rewarming or freezing. Reheat the sauce gently.

Browning the Ragù Base: Coarsely grind the giblets and veal together in a food processor fitted with the steel blade, or in a meat grinder. Heat the butter in a 12-inch heavy skillet over medium-high heat. Drop in the minced vegetables and Prosciutto di Parma. Sauté, stirring often with a wooden spatula, 3 minutes, or until the onion begins to pick up color. Add the ground meats, including the beef and the prosciutto cotto. Turn the heat up to high, breaking up the chunks and stirring to encourage even browning. A brown glaze should develop on the pan’s bottom. Take care not to burn it, as the glaze contributes important flavor to the sauce. The browning takes 8 to 10 minutes.

Reducing: Add the Marsala, reduce heat to medium, and bubble slowly, until all the liquid has evaporated. Keeping the heat at medium, add the white wine and cook it off as you scrape up the brown glaze. This should take about 15 minutes. Reduce the mushroom liquid and tomato paste down to nothing.

Simmering: Turn the ragù into a 3- to 4-quart saucepan. Stir in the stock, and adjust the heat so that the ragù is bubbling very slowly. Partially cover, and cook 30 to 40 minutes, until it resembles a thick soup.

Serving: Toss with freshly cooked pasta, and serve at once. Freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese is delicious with this ragù.

Suggestions Wine: A soft light-bodied red, like a young Santa Maddalena Classico from the Trentino—Alto Adige region or a young Valpolicella Classico of the Veneto.

Menu: Use the ragù in Domed Maccheroni Pie of Ferrara. Serve the ragù over tagliatelle or any small hollow pasta before a Salad of Mixed Greens and Fennel and a dessert of Sweet Tagliarini Tart of Ferrara. Or as a first course before Balsamic Roast Chicken or Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel. Have Riccardo Rimondi’s Spanish Sponge Cake filled with raspberry jam or Espresso and Mascarpone Semi-Freddo for dessert.

The pine nuts of Ravenna, from a 17th-century board game, by Bolognese artist Giuseppe Maria Mitelli

Il Collectionista, Milan

Behind the scenes at Ristorante San Domenico in Imola