PASTAS

Of Sacred Navels, Priest Stranglers, and the Paradise of the Poor

As early as the 14th century, trade, agriculture and strategic geographic placement made Emilia-Romagna one of Italy’s wealthiest regions. For the area’s aristocracy food was status and creativity was encouraged. Pasta became more than a single food; it became the region’s most celebrated first course.

Although each region of Italy takes pride in its own special pastas, Emilia-Romagna’s, made solely of flour and egg, are admired throughout the country. For many cooks all over Italy, they set a standard of excellence.

That excellence was no accident. It was born of wheat, trade and wealth. The region’s fertile Po River plain nourished a particularly soft and fine wheat. When blended with the area’s abundance of eggs, it became a tender pasta, best eaten fresh. Its moderate protein and starch content separated this pasta from its counterpart in southern Italy. There, wheat high in protein and low in starch produced a pasta that dried and stored well. Emilia-Romagna’s wheat yielded pasta too brittle for successful drying and storing. Hence the region’s tradition of fresh pasta began.

Pasta in Emilia-Romagna speaks of many things—traditions of birth, marriage and even death; centuries of Christmases, Easters and saints’ days, each celebrated with its special dish. Pasta speaks of geographic origin and even of a family’s social status. Pasta wittily expresses anticlerical sentiments without a word being spoken. It is steeped in legend, sometimes quite sensuous legend at that. And pasta often is so entrenched in tradition that one misstep in its preparation or presentation can outrage the most accommodating diners.

Those traditions have passed from hands to hands, through centuries of daughters watching mothers make pasta. Pasta is the food of women. Until very recently, while a woman in Emilia-Romagna could command accolades for many achievements, making superb pasta headed the list.

Almost every restaurant in the region, no matter how small or simple, has its sfoglina, a woman who comes in every morning, pours out a mountain of flour onto her work board, blends in eggs, kneads, and then hand-rolls la sfoglia, the sheet or “leaf” of golden dough. From this she fashions all the pasta served that day. She often creates enough to feed hundreds. If you showed her a food processor or a pasta machine, she would think you were mad.

The sfoglina tradition may be approaching its twilight. For years shops selling handmade pastas have supplemented the efforts of busy home cooks. As elderly sfoglinas retire and fewer young women take their places, those shops are beginning to supply restaurants. Certainly the pasta is still fresh and made by talented craftswomen; nothing less is acceptable in Emilia-Romagna. But with waning interest in the craft among young people, the region’s great culinary heritage is threatened. Handmade pasta could become a curiosity tasted only on holidays.

To celebrate the past, if not the future, this chapter reflects 500 years of Emilia-Romagna’s pasta making. You will find both classic and modern dishes. But to savor them fully, you need to understand the lively culture they evolved from.

Myth has it that pasta was poor man’s food, implying that for centuries Italian peasants survived on plates of spaghetti. Sadly that was not so in much of Emilia-Romagna. During the all-too-frequent poor harvests and famines, wheat became the exclusive property of the wealthy. The poor could get wheat only when it was abundant. Wheat pastas stretched with ground chestnuts and cornmeal still survive from those times. Polenta and beans, now eaten more out of nostalgia than necessity, were what much of Emilia-Romagna’s peasantry survived on. Pasta was really the food of the affluent until the Industrial Revolution.

Bologna’s first pasta factory was chartered by the city council on November 20, 1586. Shortly after New Year’s Day, 1587, Giovanni dall’Aglio started making “Vermicellos, Lasagnas, Macarones as they are made in Rome, Naples and Venice.”

Cookbooks of the time document court banquets where pastas with the same names were served. Recipes from those books describe doughs often flavored with rosewater, sugar, saffron and/or butter. Maccheroni “in the style of” Naples or Rome seemed to be especially chic.

Renaissance pastas often accompanied meat dishes. In Italy today, serving pasta as a side dish is culinary heresy. With very few exceptions, pasta is always a separate course. But during the 16th and 17th centuries, filled and ribbon pastas often garnished roasts and stews. Then, most pasta dishes were topped with a blend of sugar, cinnamon, and grated Parmesan-style cheese. Believe it or not, the mixture can be quite delicious, as the chapter on Renaissance pastas proves.

Sugar was a prime status symbol, displayed and used with abandon by the aristocracy. Sweet and savory flavorings were intermixed from the first courses to the last on Medieval and Renaissance menus, and were often combined in pasta fillings. Some of these still survive, like Ferrara’s cappellacci filled with sweet squash and Parmigiano-Reggiano and Parma’s old recipe for pillowlike tortelli filled with spiced fruits and chestnuts. The spirit of sweet/savory dishes lives on in the many elaborate pies of the region, pies that are seen in those magnificent still-life paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries. With their sweet crusts and fillings of savory pastas, sauces and meats, they might have been handed straight out of those old picture frames.

In the 18th century, savory and sweet parted company, with most sugared dishes presented at the end of the meal. By the early 19th century, pasta had its own place on the menu. Marie Louise, the Duchess of Parma and wife of the exiled Napoleon, prized elegant renditions of baked maccheroni cooked in the style of Naples and Spanish Aragon and served in fancy molded shapes.

Another dish favored by Marie Louise was Tortellini alla Bolognese. This is possibly the most famous and remarkable of Emilia-Romagna’s filled pastas, the centerpiece of Bolognese cuisine. First made to be served in broth, the doughnut shape allows flavorings not only to surround the tortellino, but also to flow through it for a perfectly even distribution of tastes. The meat and cheese filling needs little embellishment. Good homemade broth or a simple tossing with butter and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese is more than sufficient. Some Bolognese prefer tortellini tossed with their meaty ragù others claim the ragù overwhelms the pasta. But if pasta as a side dish is heresy in Italy, for the Bolognese tortellini salad, so common in the United States, is barbarism.

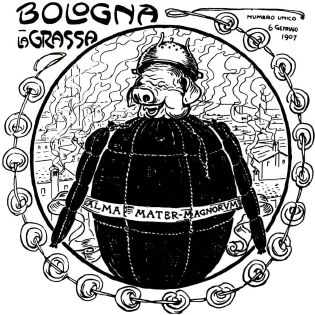

A wreath of tortellini surrounds pig and mortadella in this early 20th-century magazine cartoon of Bologna the Fat.

Il Collectionista, Milan

Although tortellini are eaten in other parts of Italy, Bologna claims them as her own. An old Bolognese legend tells of the days when the gods walked the earth, and Venus and Zeus paused for the night at a small inn near Bologna. The innkeeper was so enchanted by the goddess that just before dawn, he peeked into her bedroom. There she lay on the bed, with sheets tossed aside, sprawled in exquisite disarray. The humble man wondered how he, an illiterate, a mere cook and innkeeper, could pay compliment to such beauty. He went to his kitchen, and shortly after sunrise he emerged with a tribute to the goddess. He had modeled the little tortellino after Venus’s navel. Even now in Bologna, the pasta’s nickname is “sacred navels” (umbilichi sacri).

To this day, Bologna honors outstanding achievement in tortellini making with the Golden Tortellino, the pasta maker’s Oscar. Tortellini are stuffed with a varying blend of sautéed pork, veal, beef, and/or capon, along with prosciutto, mortadella, and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. Their delicacy is easily overpowered by complicated or highly seasoned sauces. One exception is Bologna’s tortellini pie. This holdover from the most baroque era of the Renaissance combines the pasta with an array of sauces and meats, all enclosed in a decorated sweet crust. The result brings alive an extraordinary taste of the past. Grand pies like these are reserved for holidays and special occasions.

The intricacy of the tortellino’s shape and the rich ingredients of its filling suggest the pasta began as court food. Eventually tortellini filtered down the economic scale to the middle class of merchants, land owners and professionals, and finally to the tables of laborers and peasants. Until roughly 50 years ago, the poor ate tortellini only during holiday celebrations. They usually saw meat (other than pancetta, salt pork and salami) only at Christmas and Easter. Even then, quantities were small, the meat was tough, and it needed long simmering. For these people who had so little, tortellini were a way of stretching limited amounts of precious meat. A half pound of boiled meat fills enough tortellini to feed twelve, and the meat’s broth is a delicious cooking medium for the pastas. The combination must have been more than merely filling and satisfying, it must have tasted of pure luxury.

Some Italian writers claim tortellini existed as far back as the early 10th century, but actual evidence is hard to come by. Cookbooks of the 16th and 17th centuries mention filled pastas called tortelletti and other variations on the word torta, which means cake or turnover. But thus for none of the early recipes describe its unusual shape. Tortellini shaped as we know them today were definitely eaten in Bologna by the 1830s. Vincenzo Agnollotti, Marie Louise’s cook, gives a recipe for tortellini alla Bolognese in his 1834 cookbook. Late-19th-century cookbook author Pellegrino Artusi describes three different tortellini in detail (“all’ Italiana,” “alla Bolognese,” and a last one stuffed with pigeon) in his Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well. He even supplies an illustration of the pasta’s actual size: the pasta was cut into discs 1½ inches in diameter before stuffing.

Tortellini’s much larger cousins are called tortelloni. Traditionally they are meatless, stuffed with ricotta, parsley, Parmesan, egg, and nutmeg. But greater liberties are taken with this filling. Tortelloni lend themselves to imaginative treatments inspired by a cook’s mood and inclination.

Mood and inclination combine with strong local tradition to confound anyone set on standardizing pasta in Emilia-Romagna. For the past 2,000 years so much of the region was broken up into separate and ever-changing political entities. Every province, often every town, has its own history and its own renditions of the region’s pastas. Sometimes the name changes while the pasta stays the same. Or the pasta and its filling, shape, or sauce change while the name remains the same. Hopeless but delicious confusion takes hold for anyone trying to decipher all the local subleties.

For example, tortellini and tortelloni keep their names as you go north to Modena. To the east of Bologna in Ferrara, big tortelloni become cappellacci (“big hats”), always filled with sweet squash, nutmeg, and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

South of Bologna, in Romagna, the same shape becomes cappelletti (“little hats”—even though, confusingly, the pasta may be large or small). The filling changes with location. There are at least four versions of cappelletti between the Romagna towns of Ravenna, Rimini, Forlì and Faenza, a distance of 37 miles. Some are totally meatless; others blend several meats with cheese. Each is supported by strong local tradition. Never tell a Riminese that his meatless cappelletti remind you of Bologna’s meat-filled tortellini. By regional reasoning they are two entirely different pastas.

No matter what the local variations are, however, making tortellini or cappelletti on Christmas Eve is a rite that has united women from Modena to Rimini for at least 150 years. The ritual begins when the entire family gathers for an afternoon of stretching, filling, and shaping pasta. The finished pastas are then spread on a cloth-covered table where they will rest—as though on an altar, as one chronicler of regional folkways put it. On Christmas afternoon they “die nobly” in capon broth. When the big tureen of tortellini/cappelletti is brought forth from the kitchen, the feast of Christmas officially begins.

Tortellini are not found north of Modena. In Parma rectangular tortelli have some of the significance of Bologna’s tortellini. They can be filled with sweet squash, cabbage, potato, spiced fruit or chestnuts, but Tortelli d’Erbette, rectangles of pasta stuffed with ricotta, Parmigiano-Reggiano, and mild greens, are the most popular.

Anolini are Parma’s other specialty. These small discs or half moons are filled with the braising juices of a beef pot roast cooked up to three days, butter-toasted bread crumbs, and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. Anolini are always served in broth.

When anolini move north to neighboring Piacenza, they pass through several mutations. Out on the banks of the Po in Piacenza province, they are stuffed with roast veal, pork and brains, cut with zigzag edges instead of smooth ones, and called by a new name, marubei.

Reggio adds chicken giblets to Piacenza’s filling and calls the same disc shape cappelletti. These look nothing like Romagna’s cappelletti, but they too have always been holiday food. An old saying indicates how special meat-filled pastas were: “Making love and cappelletti are the paradise of the poor.” Along Reggio’s Po embankment paradise includes a little local Lambrusco added to a deep soup plate before the hot broth and cappelletti are ladled in. The dish now tastes like an entire meal.

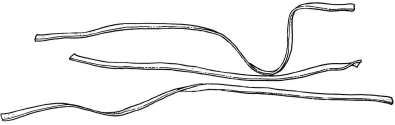

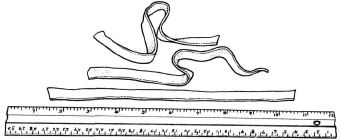

Strozzapreti look like thick, twisted tagliatelle. They were first made in Romagna long ago, when the village priest always ate for free at the local trattorie. A thick, heavy pasta was served to fill him up so he could not devour too much of the next course, which was a far more expensive commodity—meat. Strozzapreti translates as “priest stranglers.” They have different dialect names and slightly different shapes all the way from Romagna down to southern Italy.

Gramigna (“little weeds”) are small wiry cords of pasta with a narrow hole running through them. The process of making them by pressing dough through a hand-operated extruder has not changed in 200 years. Braised sausage is the traditional accompaniment.

It has been said that garganelli makes slaves of women. The first time I made them, I understood why. An egg pasta flavored with Parmigiano-Reggiano and nutmeg is cut into small squares. Each square is shaped into a ribbed hollow tube with points at either end by rolling two opposing corners of the square over each other around a dowel. The ribs are pressed into the dough by rolling the dowel over a small grooved board. The result resembles a ribbed quill (penne) pasta. Garganelli are delicious, but imagine a woman rolling one or two at a time when hundreds are needed for family dinner!

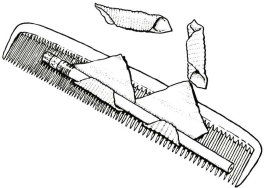

Garganelli owe their creation to hemp. They were first made near Castel Bolognese, about 25 miles south of Bologna, and are rarely eaten much farther south. Hemp flourished on that particular part of the Po plain, and every house had its hemp loom. Originally, the ribs were pressed into garganelli by rolling the pasta over the loom’s comb.

Modena, to the north, had hemp too. There garganelli are called maccheroni al pettine (“maccheroni of the comb”). Sometimes the comb was replaced by a little square frame with rough hemp cording stretched across it. Today small plastic washboards are sold to achieve the same result.

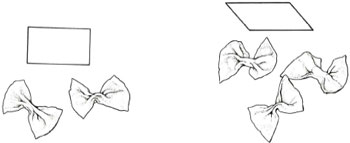

Stricchettoni are rectangles of pasta pinched in the center to make bows. Like garganelli, they are made with egg, nutmeg, and Parmigiano-Reggiano, along with pepper, and in some parts of Romagna, lemon zest. Near Modena parsley is used instead.

In Romagna stringhetti are made the same way, with the addition of lemon zest, and are cut on the diagonal before pinching.

Although not native to the region, spaghetti are well liked in Romagna. The people of Emilia rarely eat them. The pasta will always be purchased dried and boxed, made only with durum wheat and water.

Although maccheroni (today defined as dried commercial pasta made of flour and water, often in hollow shapes) have never approached the popularity of fresh egg pasta, they have been used in the region since at least the 16th century.

Tagliatelle are cut into long ribbonlike strips from rolled and thinned sheets of dough. They are one of the few pastas that retain the same name throughout the region. This golden egg pasta was supposedly first created in the 16th century by Bolognese cook Maestro Zefiramo, who was inspired by Lucrezia Borgia’s blond tresses. The infamous beauty was entertained in Bologna to honor her marriage into Ferrara’s illustrious Este family. The most versatile of pastas, tagliatelle (from tagliare, to cut) are the traditional partner to meat ragùs. One of the earliest mentions. I have found of them is in 1557, but no doubt they existed before then. When sheets of egg pasta are cut very thin they become tagliarini, taglioline and other diminutives of tagliare.

In the early 1970s, Bologna’s chapter of Italy’s gastronomic society, the Italian Academy of the Kitchen (Accademia Italiana della Cucina), attempted to define and standardize tagliatelle’s dimensions. No two cooks cut them the same size, and Italy’s pasta manufacturers have sidestepped standardization of shapes for centuries. After much research and debate, the Academy declared to the world that tagliatelle are 8 mm wide and .6 mm thick (5/16 inch wide and 1/32 inch thick). To ensure that there could be no doubt about its proper measurements, the official tagliatelle was cast in solid gold. On April 16, 1972, pasta’s “golden rule” was given a place of honor in Bologna’s city hall.

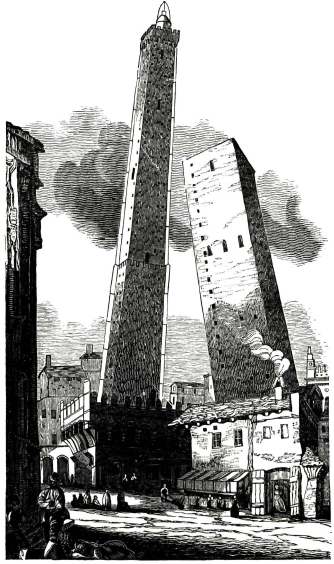

But this is only half the story. Eight millimeters wide is the easy expression of the real measurement. Bologna’s symbol to the world is her two leaning Medieval towers. Out of respect for the early origins of the tagliatelle, its true measure is 1/12,270 the height of the tallest of the two towers, La Torre degli Asinelli.

Exacting measurements or no, pasta in Emilia-Romagna is pure pleasure. I can think of no more enticing way of sharing the region’s culinary heritage than by inviting you to enjoy these recipes.

Bologna’s leaning medieval towers, the taller Asinelli and the shorter Garisenda

Homemade Pasta in the Style of

Emilia-Romagna

The mystique of fresh pasta has been exaggerated to the point that many cooks feel it must be made at the very last moment. Pasta is far better made an hour or more ahead, as it settles and collects itself with standing, resulting in a better texture.

In Emilia-Romagna pasta is often made in the morning, to be eaten later in the day. I prefer using filled pastas the same day they are made, but when pressed I have found that refrigerating them for 12 to 24 hours did no harm, except with very moist fillings that can make the pasta gummy. Unfilled pastas taste freshest when eaten within 6 to 8 hours of being rolled and cut, but are still delicious and light after drying for a week at room temperature.

Since each of the following recipes is made with the same method, I have given four lists of ingredients and one set of instructions. You can find more information on flour in A guide to Ingredients, and advice about store-bought pasta in Pastas.

Pasta all’ Uovo

[Makes enough for 6 to 8 first-course servings or 4 to 6 main-course servings,

equivalent to 1 pound dried boxed pasta]

4 jumbo eggs

3½ cups (14 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

Pasta Verde

[Makes enough for 6 to 8 first-course servings or 4 to 6 main-course servings,

equivalent to 1 pound dried boxed pasta]

2 jumbo eggs

10 ounces fresh spinach, rinsed, stemmed, cooked, squeezed dry, and finely chopped; or 6 ounces frozen chopped spinach, defrosted and squeezed dry

3½ cups (14 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

Egg Pasta with Parmigiano-Reggiano

Cheese and Nutmeg Villa Gaidello

Pasta Villa Gaidello

[Makes enough for 6 to 8 first-course servings or 4 to 6 main-course servings,

equivalent to 1 pound dried boxed pasta]

4 jumbo eggs

¼ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon each freshly ground black pepper and nutmeg, or 1½ teaspoon grated lemon zest

1½ cups (6 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

3 cups (12 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

Pasta al Vino

[Makes enough for 6 to 8 first-course servings or 4 to 6 main-course servings,

equivalent to 1 pound dried boxed pasta]

2 jumbo eggs

½ cup dry white wine

3½ cups (14 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground is best)

Making the Dough

Light, delicate pasta comes from working the dough as much as possible to develop the elasticity of the flour’s protein, or gluten. Kneading and then gradually rolling, stretching, and thinning the dough lengthens the gluten strands, producing tender and resilient pasta. Shortcutting the process results in heavy noodles. There is nothing difficult here, but like any craft the pleasure of achievement comes from learning a few basics and then practicing. Take time to work the dough well and it will pay you back tenfold in dining pleasure.

Measuring the Flour: Weighing flour on a scale is easier and more accurate than measuring by cups. Pour the flour onto the scale and you are done. If your scale is too small to neatly hold all the flour, set a medium-size paper bag on it and pour flour into the bag. There is no mess, and the bag can be used again and again.

If measuring flour by the cup is the only method available, keep in mind the following: Spoon it from the flour sack into your measuring cup and then level with the flat side of a knife blade. Resist the temptation to tamp or tap the cup before you level. A leveled cup of untamped flour weighs 4 ounces, the measure used in these recipes.

On wet and humid days a little more flour may be needed; on dry days a little less. Judge this by the feel of the dough: it should be pliable, elastic, and not too stiff.

It is better to err on the side of too much liquid than too much flour. Kneading extra flour into an overly moistened dough is much easier than working in more liquid. If you think your flour is particularly dry because of the climate or time of year, add an additional tablespoon or two of beaten egg.

Working by Hand

Equipment:

A roomy work surface, 24 to 30 inches deep by 30 to 36 inches wide. Any smooth surface will do, but marble cools dough slightly, making it less flexible than desired.

A roomy work surface, 24 to 30 inches deep by 30 to 36 inches wide. Any smooth surface will do, but marble cools dough slightly, making it less flexible than desired.

A pastry scraper and a small wooden spoon for blending the dough.

A pastry scraper and a small wooden spoon for blending the dough.

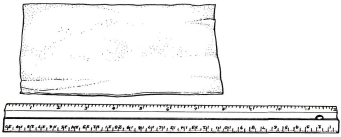

A wooden dowel-style rolling pin. In Italy, pasta makers use one about 35 inches long and 2 inches thick. The shorter American-style pin with handles at either end can be used, but the longer it is, the easier it is to roll the pasta. Long dowel pins and long American-style rolling pins can be found or ordered at kitchenware shops.

A wooden dowel-style rolling pin. In Italy, pasta makers use one about 35 inches long and 2 inches thick. The shorter American-style pin with handles at either end can be used, but the longer it is, the easier it is to roll the pasta. Long dowel pins and long American-style rolling pins can be found or ordered at kitchenware shops.

Plastic wrap to wrap the resting dough and to cover rolled-out pasta waiting to be filled. It protects the pasta from drying out too quickly.

Plastic wrap to wrap the resting dough and to cover rolled-out pasta waiting to be filled. It protects the pasta from drying out too quickly.

A sharp chef’s knife for cutting pasta sheets, or whatever cutter or equipment is specified for special shapes.

A sharp chef’s knife for cutting pasta sheets, or whatever cutter or equipment is specified for special shapes.

Cloth-covered chair backs, broom handles, or specially designed pasta racks found in cookware shops for draping the ribbon pastas. Ribbon or filled pastas can be spread on large flat baskets (inexpensive, and usually sold as cheese servers) that have been covered with a single layer of kitchen towel. The porosity of the basket and cloth helps the pasta dry evenly and protects pastas with moist fillings from becoming gummy.

Cloth-covered chair backs, broom handles, or specially designed pasta racks found in cookware shops for draping the ribbon pastas. Ribbon or filled pastas can be spread on large flat baskets (inexpensive, and usually sold as cheese servers) that have been covered with a single layer of kitchen towel. The porosity of the basket and cloth helps the pasta dry evenly and protects pastas with moist fillings from becoming gummy.

Mixing the Dough: Mound the flour in the center of your work surface. Make a well in the middle. Add the eggs, along with any liquids and flavorings. Using a wooden spoon, beat together the eggs and any flavorings. Then gradually start incorporating shallow scrapings of flour from the sides of the well into the liquid. As you work more and more flour into the liquid, the well’s sides may collapse. Use a pastry scraper to keep the liquids from running off and to incorporate the last bits of flour into the dough. Do not worry if it looks like a hopelessly rough and messy lump.

Kneading: With the aid of the scraper to scoop up unruly pieces, start kneading the dough. Once it becomes a cohesive mass, use the scraper to remove any bits of hard flour on the work surface—these will make the dough lumpy. Then knead the dough about 3 minutes. Its consistency should be elastic and a little sticky. If it is too sticky to move easily, knead in a few more tablespoons of flour. Continue kneading 10 minutes, or until the dough has become satiny, smooth, and very elastic. It will feel alive under your hands. Do not shortcut this step. Wrap the dough in plastic wrap, and let it relax at room temperature 30 minutes to 3 hours (when I am rushed I skip this step, with no ill effect on the pasta).

Stretching and Thinning: If using an extra-long rolling pin work with half the dough at a time. With a regular-length rolling pin, roll out a quarter of the dough at a time. Keep the rest of the dough wrapped. Lightly sprinkle a large work surface with flour. The idea is to stretch the dough rather than press down and push it. Shape it into a ball and begin rolling out to form a circle, frequently turning the disc of dough a quarter turn. As it thins out, start rolling the disc back on the pin a quarter of the way toward the center and stretching it gently sideways by running the palms of your hands over the rolled-up dough from the center of the pin outward. Unroll, turn the disc a quarter turn, and repeat. Do twice more.

Stretch and even out the center of the disc by rolling the dough a quarter of the way back on the pin. Then gently push the rolling pin away from you with one hand while holding the dough sheet in place on the work surface with the other hand. Repeat three more times, turning the dough a quarter turn each time.

Repeat the two processes as the disc becomes larger and thinner. (If you make pasta frequently, your body will develop a rhythm with the dough. You’ll find that your instincts will take over, with your hands and the pasta leading the way while your mind is freed for relaxation. It is a calming experience, and for some as soothing as meditation.)

The goal is a sheet of even thickness. For lasagne and filled pastas such as tortellini, anolini, and Tortelli of Cabbage and Potato the sheet should be so thin that you can clearly see your hand through it and can see colors, for instance a bright photograph. For tagliatelle, tagliarini, and other flat ribbon pastas, the dough can be a little thicker. Do not take too long in thinning and stretching as the dough starts drying out. Too-dry dough stiffens, stretches poorly, becomes lumpy, and cooks unevenly.

Cutting: Once the dough destined for tagliatelle or other ribbon-style pastas reaches its desired thickness, spread it out on a flat surface and dry 20 minutes, or until leathery in texture (turn it over several times to encourage even drying). To cut, roll up the pasta jelly roll fashion and slice it to the desired width. For special shapes, see Pastas. Instructions for filled pastas can be found in their respective recipes.

A Reliable Old Formula: An “Egg of Pasta”

Many old regional recipes simply refer to so many “eggs of pasta,” meaning 1 egg and the flour it absorbs, enough for a very generous serving of ribbon pasta. The most commonly used formula is 100 grams, or 3½ ounces (¾ cup plus 2 tablespoons), flour per egg. Of course this varies slightly with the flour’s moisture, the climate, the size of the egg, and its absorption capabilities.

I use 1 jumbo egg, instead of the more usual “large,” per 3½ ounces of flour. This moister dough builds up greater elasticity, making lighter pasta. One “egg” of my dough makes 1½ to 2 servings of ribbon pasta and much more of filled ones.

Working with Machines

Using a food processor to mix the dough and a pasta machine to thin and stretch it shortens the work time by about 30 percent. I am referring to the type of pasta machine, made of stainless steel, that has two parallel rollers with adjustable settings for thinning the dough, a hand crank (that can be fitted with an electric attachment if desired), and cutters for making wide or thin pastas.

It is true that the pebbly texture of hand-rolled pasta combines beautifully with sauces. For example, a juicy ragù melts into and joins with hand-rolled tagliatelle but slips off the slicker surface of machine-thinned noodles. Pasta purists in Emilia-Romagna consider it heresy to use a machine for stretching and thinning. But my goal is to coax you into making fresh pasta. If you find rolling by hand tedious or daunting, by all means use the pasta machine.

Note: Please do not use machines that take the dough ingredients in at one end, blend them, and then extrude finished pasta out the other end. The dough is rarely worked enough to form light, supple pasta.

Equipment: You will need the same tools as outlined in Working by Hand, with the exception of the blending implements and the rolling pin. In selecting a pasta machine, look for a sturdy one whose narrowest setting produces a very sheer pasta. Some machines’ thinnest settings still yield pasta that is too thick (Atlas brand is one). Two brands I have had success with are Altea and Imperia.

More pasta can be thinned at one time in a pasta machine equipped with extra-wide rollers. These machines are expensive and often must be ordered through commercial kitchenware suppliers. But if you make pasta often and want to cut work time, the wider rollers are handy to have.

Mixing the Dough in a Food Processor: Make sure the ingredients are cool, because a processor can overheat the eggs and the flour. Place the liquids and any seasonings in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. With the machine running, add the flour through the feed tube. Process until the dough forms a ball on the blade. It should be a bit sticky. (If it is too sticky, break it up into small clumps, sprinkle it with flour, and process again.) Now process 30 seconds, wait about 1 minute so the dough can cool, and process another 30 seconds. Remove the dough from the processor and knead it by hand a few moments to check the consistency. It should be satiny, smooth, and very elastic. At this point the dough can be stretched and thinned immediately, or covered in plastic wrap and left at room temperature up to 3 hours.

Stretching and Thinning with a Pasta Machine: Work with a quarter of the dough at a time, keeping the rest wrapped. Lightly flour the machine rollers and the work surface around the machine. Set the rollers at the widest setting. Flatten the dough into a thick patty. Guide it through the rollers by inserting one end into the space between the two rollers. Turn the crank handle with one hand while holding the upturned palm of your other hand under the sheet emerging from the rollers. Keep your palm flat to protect the dough from punctures by your fingers.

As the emerging sheet lengthens, guide it away from the machine with your palm. Pass the dough through the rollers five to six times, folding it in thirds each time. Then set the rollers at the next, narrower setting and pass the dough through three times, folding it in half each time. Repeat, passing it through three times at each successively narrower setting. Repeated stretching and thinning builds up elasticity making especially light pasta. If the sheet becomes too long to handle comfortably, cut it in half or thirds and work the pieces in tandem.

Don’t worry if at first the dough tears, has holes, is lumpy, or is very moist. Just lightly flour it by pulling the dough over the floured work surface. (Take care not to overdo the flouring, or the dough may get too stiff.) As you keep putting it through the rollers, it will be transformed from slightly lumpy and possibly torn to a smooth, satiny sheet with fine elasticity.

How Thin?: Different machines have different numbers of settings. Tagliatelle and ribbon pastas should be a bit thicker than lasagne and pastas for fillings. Usually the thinnest setting on a machine will be thin enough for you to see color and shape through it; this is perfect for lasagne and filled pastas. If it is so thin that the dough tears easily, however, stop at the next to last setting. The setting above the one for filled pastas is fine for tagliatelle and tagliarini.

Making the Shapes

Whether you have made the pasta by hand or with machines, do cut it by hand for a more authentic finish.

Garganelli: Hollow ribbed cylinders resembling quill pen points.

Use Villa Gaidello pasta, thinned until you can see color through the sheet. Have on hand a dowel about 3/8 to 5/8 inch in diameter (a round pencil works well), and a sterilized comb or the bottom of a flat woven basket. Work with a quarter of the dough at a time. Keep all but a small portion covered with plastic wrap. Cut the pasta into 1½- to 1¾-inch squares.

Make two garganelli at a time by setting two pieces close together with a corner of each square pointing toward you. Flour the dowel, and lay it across the two pieces. Roll it so the opposite corners overlap and seal, forming hollow tubes with quill-like points at both ends. Then roll the dowel over the comb or basket to make grooves in the dough. Slip the garganelli from the dowel, and arrange them in a single layer on towel-covered flat baskets to wait for cooking. Continue until all the dough is used.

Make garganelli with friends. Equip everyone with dowels or pencils, and combs or baskets, and you will have piles of pasta in no time.

Serve them in Poultry/Meat Stock, or with sauces like roasted peppers, peas, and cream, Winter Tomato Sauce, or The Cardinal’s Ragù.

Gramigna (“Little Weeds”): Wiggly cords of egg pasta made by forcing the dough through a special hand-operated press that pierces a narrow hole down their centers. Short of having your own gramigna press, this form can be simulated by rolling Egg Pasta to about 1/8 inch thick and then cutting strands about 3/16 inch wide by about 2½ inches long.

Lasagne: Large rectangles made from Egg Pasta for Lasagne Dukes of Ferrara, Lasagne of Wild and Fresh Mushrooms or from Spinach Egg Pasta for Lasagne of Emilia-Romagna. Roll thin enough for color and form to be seen through the dough, and cut into rectangles about 4 by 8 inches.

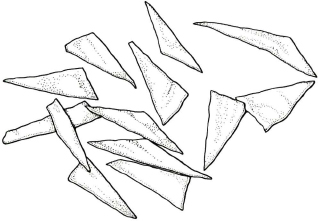

Maltagliati (“Badly Cut”): Cut rolled-up Egg Pasta at an angle to form uneven triangles and diamonds. Often used for bean soups and other country dishes.

Quadretti (“Little Squares”): Egg Pasta cut into ½-inch squares and used in broths and soups.

Stricchettoni: Bow ties in the style of Villa Gaidello. Use Egg Pasta Villa Gaidello with nutmeg, adding ½ cup chopped Italian parsley to the dough. There should be flecks of parsley, not a purée, in the pasta. If you are mixing the dough with a food processor, knead the parsley in by hand after the machine blending is finished. Cut thinned pasta sheets into rectangles about 1 by 1½ inches. Firmly pinch each rectangle in the center to make a bow shape.

Stringhetti: Bow ties in the style of Romagna. Use Egg Pasta Villa Gaidello, substituting lemon zest for the nutmeg. Cut as for stricchettoni (above), but on the diagonal forming trapezoids. Pinch in the center. Try these instead of spaghetti in Spaghetti with Shrimps and Black Olives or to replace maccheroni in Maccheroni with Baked Grilled Vegetables.

Strozzapreti (“Priest Stranglers”): These look like twisted strands of tagliatelle. Use Wine Pasta, made with water instead of wine. Roll the pasta a bit thicker than usual. Cut it into strips about 3/8 inch wide. Gently hold the top of a long strip between your palms. Slide the palms past each other, allowing the pasta to coil in opposite directions, so in profile it forms the letter “S.” Break off the coiled portion by slipping one hand down and twisting the pasta. Repeat the movement with the next portion of the strand. Do this until the strand is finished, and repeat the process with the rest of the dough. Strozzapreti are seldom perfectly neat, so do not be concerned if they appear haphazard. Spread them on a towel-lined basket.

Tagliarini: The narrowest of flat ribbon pastas. Egg Pasta is cut 1/16 inch wide and used for delicate sauces, in soups, and in the Sweet Tagliarini Tart of Ferrara.

Tagliatelle: Long flat ribbons cut just under 3/8 inch wide. That is, if you are following the “golden rule” of Bologna. In contrast to Bologna’s attempt at standardizing tagliatelle, recipes in Romagna often call for them to be cut to different widths for different sauces. This is the most versatile of pastas, substantial enough for chunky sauces, yet delicate enough for lighter ones.

Directions for shaping filled pastas appear in their respective recipes.

Storing

To Freeze or Not to Freeze: Freezing ribbon pasta does nothing to improve it. Better to dry it at room temperature and then store it in a sealed tin or plastic bag for about 2 weeks. Many filled pastas freeze well, such as tortellini, anolini, and Tortelli of Cabbage and Potato. Those with moist fillings become soggy when frozen—Chestnut Tortelli, Tortelloni of Artichokes and Mascarpone, or Cappellacci with Sweet Squash.

Cooking the Pasta

For each recipe of fresh pasta or pound of dried boxed pasta, you will need 6 to 8 quarts of boiling water seasoned with about 2 tablespoons salt (if salt is a health concern, omit it). Make sure the water is bubbling fiercely. Drop in the pasta and boil, stirring frequently, about 30 seconds to 2 minutes for fresh pastas and anywhere from 5 to 15 minutes for dried boxed examples. Taste for doneness. Perfectly cooked pasta is called al dente, meaning “to the tooth,” or still a little firm to the bite—never soft and mushy.

Once the pasta is done, drain it immediately in a large colander. Toss to rid it of excess liquid, and then blend with the sauce. Pasta, other than lasagne or others destined for baking, should never be rinsed, nor should it be partially or fully cooked ahead.

Oil in the Water?: Adding oil to the water does not protect large pastas from breaking or sticking. Rather than clinging to the pasta and making it slippery so pieces slide past each other, the oil remains on the boiling water’s surface. The best way to protect delicate pastas from breaking or big ones from sticking is to cook them in generous amounts of water, about 6 quarts per 8 ounces. Individual recipes provide specific cooking instructions.

Serving Pasta

In Emilia-Romagna today pasta is always a course unto itself, never a side dish. Even at its simplest, its texture and flavor are too complex for pairing with another dish. Whether you decide on pasta as a first course, as is traditional in Italy, or as a main dish, which is often done there as a light lunch or supper, let it stand on its own. Celebrate the pure pleasure of eating pasta with these simple guidelines:

First and foremost, pasta must be hot, so heat the dishes. The pasta will keep hot longer in shallow soup dishes than on flat plates. That traditional soup dish also makes eating the often singleminded noodles easier. Ribbon or string pastas are twirled, a few strands at a time, on the fork into neat bite-size bundles. Bracing the fork against the side of a soup dish instead of on a flat plate makes for neater dining and more elegant twirling.

If you are serving more than one pasta (as is so often done in Emilia-Romagna), offer them one after another in separate plates. Restaurants’ penchant for serving three or more pastas in tiny portions on the same plate is dining overkill. Textures and flavors become a meaningless blur.

A succession of small portions of pasta presented at a leisurely pace lets you savor each one to the full. And the cook need not be imitating an acrobatic act in the kitchen in an attempt to get several pastas out at once. Decide on the order by going from simple to complex and light to robust. For instance, start with small bowls of garganelli in Poultry/Meat Stock, then Tagliarini with Fresh Figs Franco Rossi, and finish with small portions of Pappardelle with Game Ragù.

Buying Pasta

Although logic says store-bought fresh pasta (or pasta made locally and dried) should be next best to homemade, often it is not. Do some trial tasting of fresh pastas available in your area. You may find, as I have, that some are good, but many disappoint. Doughs are often insufficiently kneaded and the stretching is done with such speed that the pasta never develops body and spring. Fresh extruded pastas like spaghetti and linguine are often heavy, as most machines in stores seem unable to work the dough with enough time and vigor to fully develop the gluten. When buying ready-made filled pastas, the dough should be sheer enough to detect the filling inside, and fillings should be delicious.

Boxed dried pasta from Italy is often preferable to commercially made fresh noodles. In Italy, dried commercial pasta and fresh pasta are not compared as better or worse, they are simply different. Having high-quality dried pasta on the pantry shelf ensures good eating when there is no time to make fresh.

The finest dried pastas are made from durum wheat (semolina is ground durum). Durum in the pasta is not the whole story, however. High-quality durum makes a springy, lively pasta, but low-quality durum produces a slack noodle.

The roughened surfaces of many dried commercial Italian pastas help hold the sauce, a characteristic much admired. When eating a good pasta, the noodle is lively and resilient in the mouth, with no sense of starchiness or heaviness. The best examples exude a wheaten flavor and are fragrant while cooking.

Flour-and-water commercial pastas are usually associated with southern Italy, while egg-and-flour pastas more strongly suggest the north. Emilia-Romagna’s dried commercial pastas are made solely with durum flour and egg.

Several excellent brands come to America from the region and can be found in specialty food stores or ordered by mail. Barilla of Parma is one of Italy’s largest manufacturers, making a wide range of shapes in a resilient, flavorful pasta. Dallari makes rough-textured, very thin, light tagliatelle, lasagne, and linguine (which, in this case, is really a tagliarini). Fini and Armando Scapinelli & Figli are two Modena companies creating pastas a bit bolder in substance, pebbly in texture, and with excellent “spring.” Although not from Emilia-Romagna, Delverde, Rusticella, Cara Nonna, and De Cecco are all good pastas. More exports should be available as our country’s interest in all things Italian keeps burgeoning. Sample new brands as you discover them to decide which are the most satisfying.

Tagliatelle with Ragù Bolognese

Tagliatelle con Ragù Bolognese

[Serves 8 to 12 as a first course, 6 to 8 as a main dish]

1 recipe Classic Ragù Bolognese or Lighter Contemporary Ragù Bolognese

10 quarts salted water

1½ recipes Egg Pasta cut into tagliatelle, or 1½ pounds imported dried tagliatelle

2 cups (8 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: Make the ragù up to 30 minutes ahead. The pasta must be cooked at the last moment and tossed with the ragù just before serving.

Making the Dish: Have a serving bowl and shallow soup dishes heating in a warm oven. Have a colander set in the sink for draining the pasta. Heat the ragù to a simmer. Bring the salted water to a fierce boil. Drop the pasta into the water and cook until tender but still a little firm to the bite. Take care with fresh pasta, as it can cook in less than a minute; dried pasta will take about 8 minutes.

Serving: Drain the pasta and toss with the hot sauce. Serve in heated soup dishes, passing the cheese separately.

Suggestion Wine: Sangiovese di Romagna is the traditional partner to Tagliatelle with Ragù Bolognese. A Sangiovese Riserva adds extra elegance. From other regions, drink a Piemontese Barbera d’Alba; or a soft and fruity Tuscan Chianti Classico or Chianti Montalbano; or a Brunello wine from young vines, the Rosso di Montalcino.

Menu: Serve in small quantities as a first course before simple roasted meats or poultry, such as Balsamic Roast Chicken. It is also often served at the beginning of elaborate holiday dinners following bowls of Tortellini in Broth Villa Gaidello and before Christmas Capon. To suit contemporary American tastes, start with a light antipasto like the Spring Salad with Hazelnuts or the Salad of Tart Greens with Prosciutto and Warm Balsamic Dressing, and then serve the Tagliatelle with Ragù Bolognese. Have fresh fruit and Sweet Cornmeal Biscuits for dessert.

Tagliatelle with Prosciutto di Parma

Tagliatelle al Prosciutto di Parma

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

5 ounces Prosciutto di Parma, sliced very thin

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 medium onions, finely chopped

6 tablespoons dry white wine

3 cups Poultry/Meat Stock, reduced to 1 cup, or 4 cups Quick Stock, reduced to 1 cup

6 to 8 quarts salted water

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut into tagliatelle or 1 pound imported dried tagliatelle

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

Freshly ground black pepper to taste

1½ cups (6 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: The sauce can be cooked up to the point of adding the stock, and then set aside up to 1½ hours (cover once the sauce has cooled). Allow about 10 minutes just before serving to cook the pasta and finish the sauce.

Making the Sauce: Trim the white fat from the edges of the prosciutto slices; chop and reserve the fat. Cut the meat into bite-size squares (do not stack the slices to cut them, as they’ll stick together), and set aside. In a large heavy skillet set over medium heat, swirl the 2 tablespoons of butter until melted and bubbly. Add the chopped prosciutto fat and the onions. Sauté the onions 10 to 15 minutes over medium heat, or until the onions are a deep golden brown. Stir often with a wooden spatula. Stir in half the prosciutto and cook 1 minute. Add the wine and simmer, uncovered, 3 minutes, or until it has totally evaporated, scraping up the brown glaze from the bottom of the skillet. Stir in the stock and heat to bubbling. Remove the pan from the heat.

Cooking the Pasta and Finishing the Sauce: Warm a serving bowl and shallow soup dishes in a low oven. Bring the salted water to a boil. Drop in the pasta and cook until tender but it still has some bite. Taste for doneness. Fresh pasta will cook in 30 seconds or more. Dried pasta takes up to 8 minutes or so. Turn the pasta into a large colander, and drain. Once the pasta is draining, quickly reheat the sauce to bubbling. Stir in the remaining 3 tablespoons butter until creamy but not fully melted (30 to 45 seconds). Add the pasta to the skillet, tossing over medium heat until thoroughly coated with sauce. Blend in the remaining prosciutto, season with pepper (salt should not be necessary), and immediately turn into the heated serving bowl. Serve, passing the cheese with the pasta.

Suggestions Wine: In Parma only one wine is sipped with prosciutto: fresh white Colli di Parma Malvasia Secco from Parma’s hills. It is low in alcohol, with some fizz, lots of fruit, and a hint of sweetness. The wine rarely leaves Parma province, and no doubt would prove too fragile to cross an ocean. Drink it there and enjoy. In the United States pair this dish with a nutty white with enough substance to back the onion sauté and stock reduction. Try a Pinot Bianco or Chardonnay from the Trentino—Alto Adige or Friuli regions.

Menu: Serve before Pan-Roasted Quail, Balsamic and Basil Veal Scallops, or any roasted or grilled meat or poultry dish not made with prosciutto. When using as a main course, either the Spring Salad with Hazelnuts or Fresh Pears with Parmigiano-Reggiano and Balsamic Vinegar makes a fine starter.

Cook’s Notes Prosciutto di Parma: See A guide to Ingredients for information on selecting a fine ham.

Tomato Variation: Tomatoes and peas are often added to this dish. Their flavors emerge best with older hams full of big, ripe flavors or with salty prosciutti. Add 2 cups of peeled and seeded fresh tomatoes, or well-drained canned tomatoes, to the onion sauté after the prosciutto has cooked for 1 minute. Omit the wine and stock. Let the tomatoes boil 3 minutes, or until thick. Heat 1 cup cooked sweet peas in the sauce just before adding the butter. Finish the recipe as described above.

Prosciutto coach, 19th-century wood engraving

Il Collectionista, Milan

Tagliatelle with Fresh Porcini

Mushrooms

Tagliatelle con Funghi Porcini

Fresh porcini are appearing more and more at specialty food markets on this side of the Atlantic. Most plentiful in autumn and spring, the mushrooms are usually imported from Italy, and are often shipped whole and frozen. My personal preference is for unfrozen porcini, with their firm, velvety texture intact. But even though defrosted mushrooms tend to be spongy, they are still delicious in this dish. Save this recipe for a time when you need a fast but elegant supper.

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

6 quarts salted water

1 to 1½ pounds fresh porcini mushrooms (smaller size preferred)

4 tablespoons (2 ounces) unsalted butter

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut for tagliatelle, or 1 pound imported dried tagliatelle

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

About 2/3 cup freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: This dish goes together in about 15 minutes and is best cooked and eaten immediately.

Sautéing the Porcini and Cooking the Pasta: Bring the salted water to a full rolling boil. Warm a serving bowl and shallow soup dishes in a low oven.

Use a damp towel to wipe away any sand and debris clinging to the mushrooms. Pay special attention to the underside of their caps. Do not immerse them in water. Cut the mushrooms into ½-inch dice. Heat the butter in a 12-inch skillet over medium heat. Raise the heat to medium-high, add the mushrooms, and sauté 3 to 5 minutes, or until browned. Lower the heat to medium and cook another 6 to 7 minutes, or until tender.

While the mushrooms are cooking, drop the pasta into the water. Boil fiercely until pasta is tender but still a little firm to the bite. Fresh pasta can cook in a matter of seconds; dried pasta can take about 8 minutes. Drain immediately in a colander. Once the mushrooms are tender, season them with salt and pepper. Add the hot pasta to the skillet and toss to blend. Add the cheese and toss to thoroughly coat the pasta.

Serving: Turn the pasta into the heated bowl, and serve immediately.

Suggestions Wine: Drink a full white like Arneis from Piemonte, Lugana of Lombardy, or Tuscany’s Montecarlo.

Menu: Serve before Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken, Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, Christmas Capon, or Rabbit Dukes of Modena. Offer as a main dish after the Salad of Tart Greens with Prosciutto and Warm Balsamic Dressing, Fresh Pears with Parmigiano-Reggiano and Balsamic Vinegar, “Little” Spring Soup from the 17th Century, or Modena’s Spiced Soup of Spinach and Cheese. Have Ugo Falavigna’s Apple Cream Tart for dessert.

Cook’s Notes Porcini Mushrooms: See A guide to Ingredients for information on porcini.

Using Olive Oil: A delicate extra-virgin olive oil from Liguria, the Veneto, or Sicily can be substituted for the butter. See A guide to Ingredients for information on olive oils.

Only Tagliatelle Will Do

I wish I had a nickel for every pound of fresh tagliatelle made in Bologna to go with Ragù Bolognese. Although ragùs are eaten with maccheroni, pappardelle, garganelli, and lasagne, tagliatelle is its most popular partner. These ribbons of egg pasta are just the right width to hold the nubbins of meat and vegetable, absorb the ragù’s juices, yet not be overwhelmed by it. In the mouth, tagliatelle and ragù taste right together; they occupy equal space on the palate and blend perfectly. Chunkier sauces often balance better with bigger maccheroni or pappardelle, and in other parts of Emilia-Romagna such choices are not questioned. But when dining in the style of Bologna, where tagliatelle was first created, only this pasta will do.

Tagliatelle with Balsamic Radicchio

Tagliatelle con Radicchio e Aceto

Balsamico

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 or 5 as a main dish]

1½ pounds radicchio (4 to 5 heads)

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 ounces thinly sliced pancetta, minced

1 large red onion, minced

2 large cloves garlic, minced

20 large fresh basil leaves, chopped, or 2 teaspoons dried basil

2/3 cup Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock, or 1/3 cup Meat Essences

14- to 16-ounce can tomatoes, thoroughly drained, or 1 pound fresh tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped

1 generous pinch freshly ground black pepper

Salt to taste

6 to 8 quarts salted water

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut into tagliatelle, or 1 pound imported dried tagliatelle

4 to 6 tablespoons commercial balsamic vinegar

1½ cups (6 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: The radicchio can be cooked up to 8 hours before serving; cool, cover, and refrigerate until ready to reheat. Finish the sauce and cook the pasta just before serving.

Braising the Radicchio: Cut the radicchio heads in half, core them, and then cut each half into six wedges. Slice into wide shreds, yielding about 12 cups. Set aside 2½ to 3 cups for finishing the sauce. Cover and refrigerate the radicchio if held more than an hour or so.

Heat the olive oil in a large sauté pan (the bigger the better, as the radicchio needs plenty of room), and cook the pancetta over medium to low heat. Stir occasionally, and adjust the heat so the pancetta slowly gives off its fat while barely browning. After about 10 minutes the pancetta will be tinged with gold and almost transparent. Turn the heat to high. Add the onion and radicchio (except the reserved portion), and cook, uncovered, stirring occasionally, until the radicchio has wilted and a dark brown glaze has formed on the bottom of the pan. Stir in the garlic and basil, and cook a few seconds. Keep the heat high and add the stock or meat essences. As the liquid comes to a boil, scrape up the brown bits from the bottom of the sauté pan but do not boil down the liquid. Crush the tomatoes as you add them to the pan. Sprinkle with black pepper. Stir the braising radicchio while it boils over high heat. After about 3 minutes it should be thick, with most of the liquid from the tomatoes cooked off. If it is still watery, cook another minute or two. Then remove from the heat, and season to taste with salt.

Cooking the Pasta: Have a serving dish and shallow soup dishes warming in a low oven. Bring the salted water to a vigorous boil. Drop in the tagliatelle, wait a few seconds for them to soften, and stir with a wooden spoon to keep the pieces from sticking. Boil about 30 seconds to 1 minute for fresh pasta and up to 8 minutes for dried, stirring frequently. Taste for doneness. When it is tender but still firm to the bite, drain immediately in a large colander.

Finishing and Serving: While the pasta cooks, quickly reheat the braised radicchio over high heat. Add the drained pasta to the pan along with the balsamic vinegar, and toss over medium heat to blend. Start with 4 tablespooons of the balsamic, adding more to taste. The vinegar should give sweet/tart flavor to the radicchio but not dominate the dish with too much acid. Toss in about half the reserved radicchio, and then turn the pasta into the serving dish. Sprinkle with the remaining raw radicchio, and serve. Pass the cheese separately.

Suggestions Wine: The tangy quality of this dish calls for a red that is all fruit and youth, like a young Sangiovese di Romagna, or a young Merlot from the Veneto or Friuli regions.

Menu: I like the Tagliatelle with Radicchio as a supper main dish. Start with a few slices of good salami and coppa or Mousse of Mortadella, serve the pasta, then offer shales of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese with the last of the wine. Dessert could be pears or clusters of grapes. Serve as a first course before Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, Pan-Roasted Quail, or almost any grilled or roasted meat or poultry not seasoned with basil or balsamic vinegar.

Cook’s Notes Radicchio: Check radicchio for bitterness by tasting near the center of a leaf. Counteract bitterness by increasing the stock to 1 cup (or Meat Essences by 2 tablespoons) and adding an additional ½ cup well-drained tomatoes.

Balsamic Vinegar: A rich, well-balanced balsamic vinegar makes this dish sing. See A guide to Ingredients for selecting vinegars.

Tagliatelle with Light Veal Ragù

Tagliatelle con Ragù Vecchio Molinetto

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

1 recipe Light Veal Ragù with Tomato

6 to 8 quarts salted water

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut for tagliatelle, or 1 pound imported dried tagliatelle

2 cups (8 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: The sauce is best eaten the same day it is cooked. Cook the pasta and toss it with the ragù just before serving.

Making the Dish: Have a serving bowl and shallow soup dishes warming in a low oven. Reheat the ragù, adding the tomatoes only 5 to 10 minutes before the sauce is tossed with the pasta.

Bring the salted water to a full boil. Drop in the pasta, and boil fiercely until tender but still pleasantly firm to the bite. Fresh pasta will take 30 seconds to several minutes. Dried pasta needs about 8 minutes. Do taste for doneness. Drain immediately in a colander, and toss with the hot ragù.

Serving: Present at the table, passing the cheese separately.

Suggestions Wine: See recommendations in the ragù recipe, Ragùs.

Menu: In addition to the menu suggestions in the ragù recipe, offer the ragù as a main dish after “Little” Spring Soup from the 17th Century, and follow with the Salad of Spring Greens. Have Frozen Hazelnut Zabaione with Chocolate Marsala Sauce as dessert.

Tagliatelle with Caramelized Onions

and Fresh Herbs

Tagliatelle con Cipolle e Erbucce

Few pasta recipes celebrate fresh herbs quite like this one. The blending of sautéed onion, cream and lively herbs is adapted from a recipe by Ido Migliari, who with his family runs Trattoria da Ido, tucked away along the canals of Ferrara’s countryside. Ido and his son gather wild salad greens from neighboring fields, then sauté them with fresh herbs to sauce tagliatelle. This version captures the fresh, bright quality of his own.

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

4 medium to large onions, chopped

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

2 large cloves garlic, minced

1½ cups Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut into tagliatelle, or 1 pound imported dried tagliatelle

6 to 8 quarts salted water

12/3 cups tightly packed fresh herbs (basil, marjoram, rosemary, sage, and thyme)

2/3 cup heavy cream

1 to 2 ounces thinly sliced Prosciutto di Parma, chopped

3 tablespoons minced Italian parsley

8 large whole scallions (green and white parts), chopped

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

2 cups (8 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: Once stock is in the sauce, the sauce can be set aside, covered, 2 to 3 hours.

Making the Sauce: Heat the oil in a large heavy sauté pan over medium heat. Add the onions and a light sprinkling of salt and pepper. Stir them to lightly coat with the oil, then cover the pan, and lower the heat to the lowest possible setting. Cook 25 to 30 minutes, or until the onions are soft and almost transparent. Once the onions’ natural sweetness has been accentuated by slow cooking, you can bring out their rich, savory side with browning. Uncover and raise the heat to medium-high or high. Sauté the onions to deep golden brown, stirring often with a wooden spatula and scraping up the brown glaze collecting on the bottom of the pan. Take care not to let the glaze burn. If necessary, lower the heat slightly. Onions will resemble a thick, amber marmalade.

Turn the heat to low and blend in the garlic. Cook, stirring often, about 5 minutes. Add the stock and simmer until reduced by about one quarter. As the stock bubbles, scrape up the brown glaze from the bottom of the pan with a wooden spatula.

Finishing the Sauce and Cooking the Pasta: Roughly chop the herbs before starting to cook the pasta (see Cook’s Notes). Bring the pasta water to a fierce boil. If using fresh pasta that cooks in almost no time, reheat the sauce as the water is heating. If using dried pasta, the sauce can be reheated while the pasta is cooking. Drop the pasta into the water, stir once it softens, and continue boiling, stirring occasionally, until a tasted piece is tender but still firm enough to have a little bite. Drain in a colander.

To finish the sauce, reheat the onion mixture over medium-high to high heat and add the cream. Stir until the cream begins to bubble. Before going to the next step, have the cooked pasta draining and hot. Warm soup dishes and a serving bowl. Stir the prosciutto, parsley, scallions, and herbs into the sauce. Cook only long enough to heat through—the fresh, uncooked taste of the herbs is important here. Season to taste with salt and pepper, and then quickly toss the sauce with the pasta and about 2/3 cup of the cheese. Serve immediately in the warmed dishes, passing the remaining cheese separately.

Suggestions Wine: An Albana Secco from Romagna, Trebbiano del Lazio from near Rome, or Tocai dei Colli Orientali del Friuli from northeastern Italy.

Menu: This stands on its own as a light main dish. Start with Garlic Crostini with Pancetta, or thin slices of salami and Balsamic Vegetables. In summer iced melon with mint, or fresh peaches sprinkled with a rich balsamic vinegar make superb endings. In cooler weather try Zabaione Jam Tart. Offer as a first course before Lamb with Black Olives, Mardi Gras Chicken, or Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel.

Cook’s Notes Olive Oil: A flowery oil like those from the Imperia area of Liguria make a backdrop for the herbs and cream. See A guide to Ingredients for information.

Fresh Herb Blend: Make the major part of the mixture fresh basil and marjoram accented by small amounts of fresh rosemary, sage and thyme. When harvesting your own herbs for this dish, remember most herbs (especially basil) peak in flavor just before flowering. Before roughly chopping the herbs, finely chop the rosemary and sage. Their assertive flavors could overwhelm the palate if eaten in larger pieces.

Tagliatelle with Radicchio

and Two Beans

Tagliatelle e Fagioli con Radicchio

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

1 pound radicchio (3 to 4 heads)

5 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 large and 1 medium onion, cut into thin strips

15-ounce can chick-peas, rinsed and drained

1¼ cups cooked borlotti, bolita, or pinto beans (16-ounce can, rinsed and drained) (see Note)

2 large cloves garlic, minced

1 cup Poultry/Meat Stock or Quick Stock

1/3 cup Meat Essences, or ½ cup Poultry/Meat Stock (see Note)

2 teaspoons imported Italian tomato paste

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

6 to 8 quarts salted water

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut into tagliatelle, or 1 pound dried imported tagliatelle

1½ cups (6 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Method Working Ahead: The sauce can be completed several hours ahead. Cool and cover it until you are ready to cook the pasta.

Preparing the Radicchio: Tear away any spoiled areas on the outer leaves. Quarter the heads vertically, core them, and then cut them horizontally into thick shreds.

Making the Sauce: Heat the oil in a 12-inch sauté pan over high heat. Add the onions and cook, tossing with two wooden spatulas, 4 to 5 minutes, or until medium gold. Push the onions to the side of the pan and add the radicchio. Cook over high heat, uncovered, 5 to 8 minutes, stirring often, until a brown glaze has formed on the bottom of the pan and the radicchio has wilted.

Turn the heat down to medium, add the chick-peas and the beans, and cook, stirring, for about 5 minutes. Add the garlic and stir about 1 minute. Blend in the stock, Meat Essences (or additional stock), and the tomato paste. Turn the heat to high, and boil 3 minutes, stirring often, to concentrate the flavors. Season the sauce to taste and keep it warm over low heat.

Cooking the Pasta and Serving: Bring the salted water to a fierce boil, drop in the pasta, and cook until tender but still a little firm to the bite. Fresh pasta will cook in 30 seconds to several minutes; dried pasta will take about 8 minutes. Drain the pasta in a colander, and toss with the hot sauce and 4 tablespoons of the cheese. Pass the remaining cheese separately.

Variation: Triangles of maltagliati pasta can be substituted for the tagliatelle.

Suggestions Wine: A young Sangiovese di Romagna, or a Salice Salentino Rosso from Apulia.

Menu: This substantial dish stands on its own as a simple main dish. If you are using it as a first course, follow with Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary or Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken.

Cook’s Notes Stock: If you are using 1½ cups stock and no Meat Essences, boil the stock in a separate pot until it is reduced by about one third before adding it to the sauce.

Meat Essences: Using Meat Essences in such a typically peasant dish like pasta and beans gives away the elegant restaurant origins of this recipe. Pasta and beans are the foods of survival; Meat Essences is the food of affluence.

Radicchio: Taste a little raw leaf near the core before cooking. If bitter, soften its impact with another 3 tablespoons Meat Essences or 1/3 cup Poultry/Meat Stock.

Radicchio is often ridiculously expensive. Save this dish for the season when less expensive radicchio is coming from local sources. Also the amount could be halved with no change to the cooking instructions. The dish will be less robust and tart, but still very good.

Borlotti Beans: These dried Italian beans are plump and colored a pink-beige with maroon to black streaks and speckles. They taste meaty and full-bodied. Find them, dried and canned, in Italian groceries and specialty food markets. The pink/brown bolita bean or the speckled pinto bean from the United States’s Southwest can be substituted when borlotti are not to be found.

Tagliatelle with Fresh Tomatoes and

Balsamic Vinegar

Tagliatelle con Pomodori e Aceto

Balsamico

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

¾ cup commercial balsamic vinegar

2 large cloves garlic, minced

1 medium to large red onion, cut into ½-inch dice

6 to 8 quarts salted water

8 large vine-ripened tomatoes (about 3½ pounds), cored and cut into bite-size pieces

2/3 cup tightly packed fresh basil leaves, minced

Generous amount freshly ground black pepper

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut for tagliatelle, or 1 pound dried imported tagliatelle

Salt to taste

1¼ cups (5 ounces) Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, shaved with a vegetable peeler

Method Working Ahead: This dish is made in almost no time. It does not benefit from being prepared ahead.

Marinating the Tomatoes: Measure the vinegar into a medium-size glass or pottery bowl. Add the garlic and onion. Marinate about 15 minutes. Set the salted water on to boil. Fold the tomatoes, basil, and pepper into the vinegar mixture and let stand 10 to 15 minutes to blend flavors.

Cooking the Pasta and Serving: Drop the pasta into the boiling salted water. Cook at a fierce rolling boil 30 seconds to several minutes for fresh pasta, and up to 6 or 7 minutes for dried. Taste to make sure the pasta is tender but still a little firm to the bite. Drain the pasta in a colander, and toss it with the tomato mixture. Season to taste, and serve topped with the shaved cheese.

Suggestions Wine: Even though balsamic vinegar can be smooth and sweet, it is acidic. The quantity used here discourages most wines. Save the wine for sipping with Parmigiano-Reggiano after the pasta.

Menu: Serve before grilled or roasted main dishes not prepared with tomatoes or balsamic vinegar, such as Herbed Seafood Grill or Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken. On hot summer nights enjoy it as they do in Modena—outdoors, served as a main dish, followed by shales of Parmigiano-Reggiano and then fresh peaches.

Cook’s Notes Balsamic Vinegar: I have adapted this dish from its Modena original using a fine commercial balsamic vinegar, the sort available throughout the United States. For information see A guide to Ingredients. If good fortune brings you a generous amount of artisan-made balsamic vinegar from Modena or Reggio, savor the dish in all its authenticity: Reduce the quantity of vinegar to ½ cup; halve the amount of garlic, onion, and basil; and use only 2 ounces of Parmigiano-Reggiano.

Tagliarini with Fresh Figs Franco Rossi

Tagliarini ai Fichi Ristorante Franco

Rossi

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course]

6 to 8 quarts salted water

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut for tagliarini, or 1 pound imported dried tagliarini

8 tablespoons (4 ounces) unsalted butter

Shredded zest of 1 large lemon

12 large ripe figs, peeled and coarsely chopped

Generous pinch of red pepper flakes

Heaping ¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 cup heavy cream

1¼ cups (about 5 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Salt to taste

Method Working Ahead: This dish comes together in a matter of minutes. The trick is not overcooking the figs. You must be cooking and draining the pasta just as the sauce is ready to be blended with it. If this seems too much of a juggle, first give your full attention to cooking the pasta. Just before draining it, start heating the butter. Then drain the pasta and quickly cook the sauce. Warm a serving bowl and shallow soup dishes in a low oven about 20 minutes ahead so they are waiting when you are ready to serve.

Cooking the Pasta: Bring the salted water to a fierce boil. If you are using dried pasta, cook it about halfway, 4 minutes. Meanwhile, melt the butter in a 12-inch heavy skillet over medium heat. If you are using fresh pasta, drop it into the water once the butter has melted.

Making the Sauce: Just before starting to cook the sauce, taste the pasta for doneness. If you feel it might be ready within a few moments, keep your eye on it and wait to cook the figs. Better to have the pasta draining a few extra minutes than to have overcooked, mushy figs.

Raise the heat under the skillet to high, add the lemon zest, and cook about 30 seconds. Add the figs and both peppers. Cook over high heat 1 minute, searing on all sides by turning them gently with two wooden spatulas.

The letter “H,” 17th-century engraving, by Bolognese artist Giuseppe Maria Mitelli

Casa di Risparmio, Bologna

Assembling and Serving: Once the figs are seared, quickly drain the pasta (if you have not already done so) and add it to the skillet with the cream. Toss the pasta with the figs and cream no more than 30 seconds. Add the cheese and toss until blended. Taste for salt. Turn the pasta from the skillet into a heated serving bowl or individual soup dishes, and serve immediately.

Suggestions Wine: A soft flowery white with some fruit and spice is needed here. In Bologna it would be a Pinot Bianco dei Colli Bolognesi. On this side of the ocean, Tocai from Italy’s Friuli region is found more easily. A well-made Chenin Blanc also works well.

Menu: In a simple menu, figs with tagliatelle are a fine prelude to Pan-Roasted Quail or Porcini Veal Chops. Create a menu echoing the Renaissance (“echo” because a typical period menu had between 30 and 100 dishes) by beginning with a few slices of Prosciutto di Parma, then offering small bowls of “Little” Spring Soup from the 17th Century, then pasta with figs, followed by Christmas Capon. Make the dessert either Paola Bini’s Sweet Ravioli or Capacchi’s Blazing Chestnuts.

Variation with Dried Figs: The fresh fig season is fleeting, especially in the middle of the United States. My dried fig variation of Franco Rossi’s dish has become a favorite supper around the Christmas holidays.

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course]

8 tablespoons (4 ounces) unsalted butter

1 pound dried California Calimyrna figs, trimmed of stems and cut into eighths

Shredded zest of 1 large lemon

Generous pinch of red pepper flakes

Generous ¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¼ cup dry white wine

1 cup heavy cream

6 to 8 quarts salted water

1 recipe Egg Pasta cut into tagliarini, or 1 pound imported dried tagliarini

1½ cups (6 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Salt to taste

Follow the directions as above, but add the figs and zest to the hot butter together. Cook the figs until their skin is golden brown. Then add the wine and boil it off. Add the cream, bring to a simmer, and then add the drained pasta and toss with sauce and cheese. Serve immediately.

Linguine with Braised Garlic and

Balsamic Vinegar

Linguine con Aglio e Balsamico

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil or unsalted butter

8 large cloves garlic, cut into ¼-inch dice

6 quarts salted water

1 pound imported dried linguine, or 1 recipe Egg Pasta cut into tagliarini

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil or unsalted butter

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

1 to 1½ cups (4 to 6 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

8 to 10 teaspoons artisan-made or high-quality commercial balsamic vinegar (if using commercial, blend in 1 teaspoon brown sugar)

Method Working Ahead: The garlic can be braised up to 8 hours ahead. Set it aside, covered, at room temperature. The dish is best finished and eaten right away.

Braising the Garlic: In a large heavy skillet, heat the 3 tablespoons oil or butter over medium-low heat. Add the garlic, and lower the heat to the lowest possible setting. Cook, covered, 5 minutes. Uncover and continue cooking over the lowest possible heat 8 minutes, or until the garlic is barely colored to pale blond and very tender. Stir it frequently with a wooden spatula. Do not let the garlic turn medium to dark brown, as it will be bitter.

Cooking the Pasta: Warm a serving bowl and shallow soup dishes in a low oven. As the garlic braises, bring the salted water to a fierce boil, and drop in the pasta. Stir occasionally. Cook only a few moments for fresh pasta, and up to 10 minutes for dried pasta. Taste for doneness, making sure the pasta is tender but still firm to the bite. Spoon about 3 tablespoons of the cooking water into the cooked garlic just before draining the pasta. Drain in a colander.

Finishing and Serving: Remove the garlic from the heat and add the hot drained pasta. Add the additional 3 tablespoons of oil or butter (the fresh taste of uncooked oil or butter brightens the dish), and toss with two wooden spatulas. Season with salt and pepper. Now toss with all of the cheese. Turn into the heated serving bowl. As you serve the pasta, sprinkle each plateful with a teaspoon or so of the vinegar.

Suggestions Wine: A simple but fruity white, like Trebbiano del Lazio or Frascati.

Menu: Serve before simple or complex dishes: Herbed Seafood Grill, Braised Eel with Peas, Christmas Capon, Beef-Wrapped Sausage, Lamb with Black Olives, or Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel. Offer as a main dish after Prosciutto di Parma, Mousse of Mortadella, Garlic Crostini with Pancetta, Chicken and Duck Liver Mousse with White Truffles, or Valentino’s Pizza. Have Riccardo Rimondi’s Spanish Sponge Cake for dessert.

Cook’s Notes Balsamic Vinegar: See A guide to Ingredients for information on selecting balsamic vinegars.

Variation with Fresh Basil: In summer add 1 cup coarsely chopped fresh basil leaves to the braised garlic a few seconds before tossing with the pasta. Let the basil warm and its aromas blossom, then add the pasta to the pan.

Tagliarini with Lemon Anchovy Sauce

Tagliarini con Bagnabrusca

[Serves 6 to 8 as a first course, 4 to 6 as a main dish]

Sauce

10 whole salted anchovies, or two 2-ounce cans anchovy filets

1 cup cold water

6 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

6 tablespoons minced Italian parsley

1 large clove garlic, minced

½ cup water