During the Renaissance, Italian pasta was seasoned by spices of every description—spices long used in the cuisines of ancient Persia and Arabia, Southeast Asia and China. The affluent Italian’s taste for sweetness and spice was heightened by Medieval trade links with the East and Arab occupations of southern Italy. So many old Italian court recipes seem influenced by the Middle East. Sweet spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, clove and ginger were accented by pepper, perfumed with rosewater, or their sweetness took on arid/herbal overtones from generous doses of saffron. These blends, in turn, were mixed into dishes with nuts, fruits, meats and cheeses.

The ancestors of today’s filled pastas were stuffed with these combinations and then sprinkled with grated cheese, sugar, and cinnamon. On the religious calendar’s many meatless days, when one ate magro, or lean, pasta was cooked in milk or water. Broth of game or meat was the cooking medium on meat-eating, or fat (grasso) days. Those forerunners of present-day pastas evolved in remarkable settings. The Renaissance was a time of lavish banquets, a time when the foundations of modern cuisine were gradually taking shape in the noble kitchens of Italy. Her foods and manners were emulated, debated, and often envied throughout the Western world.

A typical menu of the period had a minimum of three courses, each with five to twenty or more dishes. Basic banquet etiquette called for covering tables in silky linen and changing the tablecloths up to three times during a meal. Fashion dictated centerpieces of Greek gods romping through mythical settings, the sculptures carved from sugar paste, then gilded with sheets of gold and silver and painted in bright enamels. Each place setting was marked by napkins folded to resemble sailing ships, fanciful beasts, or flowers. Washing hands with scented waters between courses was accepted ritual. Music, short plays, and dancing supplied a change of pace between courses.

Sweet and savory flavors dominated dishes throughout the meal. Sugar was expensive, a status symbol, and used lavishly. Pasta had not yet taken its place as solely a first course. It appeared from first dishes to last.

The first course always came from the credenza, or sideboard. Imagine a Welsh cupboard—like arrangement, a flat serving table backed by shelves. On those shelves your host displayed his best silver, gold, and pottery. Below, the tabletop was covered with a mosaic of room-temperature dishes arranged in perfect symmetry. Once the guests were ready, the entire collection of dishes was carried to the dining tables. There the multiple servings—green salads, bright fruits, cured meats, cold roasts, cheeses, marzipan, sweet tartlets, and perhaps pasta sprinkled with sugar, cheese, and cinnamon—were set out again in a symmetrical display.

After the first course was carried away by servants, a second service came hot from the kitchen. Great pies covered with decorated crusts and filled with meats and/or pastas were paraded before the guests. Platters of hammered silver were mounded with roasts and stews, often nested into beds of filled or ribbon pasta. At an elaborate feast there would be two, three, four, and even five of these courses from the kitchen.

The last course came again from the sideboard: vegetables dressed in vinegar and pepper, candied and fresh fruits, little cakes and pastries gilded with sugared seeds of melon or anise, savory tarts, fresh fennel to sweeten the breath, and perhaps squares of pasta filled with sugar, spices, fresh cheese and rosewater.

Descriptions of these feasts and foods of Emilia-Romagna are preserved in books and chronicles of the period. Four of them are especially useful. Two were written in the region, the other two were created by cooks native to the region, but working elsewhere.

Christofaro di Messisbugo was the scalco or major duomo to the Cardinal Hippolito d’Este at the 16th-century court of Ferrara. His two books, Banquets (Banchetti) and New Book (Libro Novo), published in 1549 and 1552, record banquets, recipes and details of kitchens and pantries. One hundred years later Carlo Nascia was cooking for the Duke of Parma, Ranuccio II, and writing his Four Banquets Destined for the Four Seasons of the Year (Li Quatro Banchetti Destinati per le Quatro Stagioni dell’Anno). Nascia’s eye for detail is limited to the kitchen. Interestingly, there are few recipes for pasta. At about the same time Bartolomeo Stefani traveled from his native Bologna across the Po River to cook for the Gonzaga family, rulers of Mantua. His small book, The Art of Cooking Well (L’Arte di Ben Cucinare), was published in 1662 with not one pasta dish. Writing a few decades after Messisbugo, Bolognese Bartolomeo Scappi chronicled the banquets of nobles and churchmen. He cooked in Rome for Pope Pius V and wrote one of the period’s most complete and extensively illustrated cookbooks containing many pasta recipes.

These records present pasta as court food, rather than food of the commoner. The white flour that produced the lightest pasta was the exclusive property of the wealthy. Today these sweet and savory recipes stand on their own as new and interesting pasta dishes. Certainly they speak of that glamorous era, but their exotic and unusual flavors fit very much into the world of the 20th century, where new tastes are embraced with such enthusiasm.

Christofaro di Messisbugo, 16th-century Ferrara cookbook author. Engraving from 1547.

Il Collectionista, Milan

Tagliatelle with Caramelized Oranges and Almonds

Tagliatelle con Arance e Mandorle

At 16th-century banquets this pasta accompanied poultry and meats. Try the combination with Christmas Capon for an important dinner. The sweet pasta makes an unexpected and very good dessert.

[Serves 10 to 12 as dessert or as a side dish with Christmas capon]

1 quart water

3 large Valencia or navel oranges

8 tablespoons (4 ounces) unsalted butter

1½ cups orange juice

2/3 cup sugar

Generous 1/8 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

6 quarts salted water

1 recipe Wine Pasta, or 1 pound imported dried tagliatelle

3 to 4 tablespoons sugar

½ to 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

2/3 cup (5 ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

1 cup whole blanched almonds, toasted and coarsely chopped

Method Working Ahead: The sauce can be made several hours ahead; cover and set it aside at room temperature. Reheat to bubbling before adding the pasta.

Preparing the Orange Zest: Bring the 1 quart water to a boil. Using a zester, remove the zest from the oranges in thin, long strips. Boil 3 minutes. Drain in a colander, rinse with cold water, and set aside.

Making the Sauce: Melt the butter in a large skillet over medium heat. Using a wooden spatula, stir in about ¼ cup of the orange juice and the 2/3 cup sugar. Melt the sugar in the butter over medium heat, frequently stirring in more spoonfuls of orange juice to keep the sauce from crystallizing (reserve about 1/3 cup for finishing the sauce). Once the sugar has dissolved, turn the heat to medium-high and stir occasionally as the mixture slowly turns amber, about 2 minutes. Once it reaches deep golden amber, blend in the pepper and two thirds of the orange zest. Cook only a second or two, to protect the zest from burning. Step back from the skillet and, at arm’s length, pour in the last 1/3 cup of orange juice. It will bubble up and possibly spatter, then will thin the sauce to the ideal consistency. Turn off the heat.

Cooking the Pasta: Have a large platter and dessert dishes warming in a low oven. (If you are serving this with the capon, the bird should be ready. Bring the salted water to a boil. Drop in the pasta, and cook until tender but still a little resistant to the bite. Drain in a colander. Reheat the sauce to a lively bubble. Add the pasta to the skillet, and toss to coat thoroughly. Turn it onto the heated platter, and sprinkle with the sugar, cinnamon, cheese, almonds, and lastly, the remaining orange zest. Mound small portions on heated dessert plates, and serve hot. Or place the capon atop the pasta, and serve.

Suggestions Wine: From Emilia-Romagna, a fruity and softly sweet Albana di Romagna Amabile (amabile is sweet), or Sicily’s white Malvasia delle Lipari. With the capon and pasta a red Recioto della Valpolicella Classico Amarone.

Menu: Offer as dessert after a meal that evokes the 16th century: Start with Modena’s Spiced Soup of Spinach and Cheese, then serve Rabbit Dukes of Modena, and a simple salad. Serve the tagliatelle and capon after “Little” Spring Soup from the 17th Century. For dessert, Marie Louise’s Crescents.

Torta di Vermicelli Carlo Nascia

Straight from the ducal banquet tables of 17th-century Parma, this thick pasta “pancake” is crisp and golden on the outside, spicy and crumbly on the inside. It is served hot, with a sugar syrup. In the time of Carlo Nascia, cook to the Duke of Parma, it accompanied savory dishes. Although for modern tastes the vermicelli cake makes a good dessert, try it too, cut into wedges and served alongside slices of roast venison, wild duck, hare, pork, or veal as they used to eat it in Parma.

[Serves 8 to 10 as dessert or side dish]

Sugar Syrup

½ cup sugar

1 cup water

Spiced Bread Crumbs and Pasta

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 cup fresh bread crumbs made from half-stale bread

¾ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1/8 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

Generous pinch of freshly ground black pepper

6 quarts salted water

10 ounces imported dried vermicelli or cappellini

6 tablespoons vegetable oil

5 tablespoons (2½ ounces) unsalted butter

Method Working Ahead: The sugar syrup can be made 1 week ahead; cover and refrigerate until needed. Prepare the bread crumbs up to several hours ahead. Let them stand, covered, at room temperature until needed.

Making the Sugar Syrup: Combine the sugar and water in a small saucepan, and boil 3 minutes, or until the sugar has completely dissolved. Set aside.

Toasting and Spicing the Bread Crumbs: In a 10-inch heavy skillet, heat the olive oil over medium heat. Add the bread crumbs and cook, stirring frequently, 4 minutes, or until golden. Take care not to burn them. Turn them into a small bowl and add the cinnamon, nutmeg, and pepper. Taste for balance. The spices should blend with no one taste standing out, except a tingle from the pepper. Wipe the skillet out with a thick wad of paper towels.

Cooking the Pasta: Bring the salted water to a boil. Add the pasta and cook 2 minutes, or until slightly underdone. Drain it in a colander, tossing to rid it of excess liquid.

Cooking the Pancake: Have a serving platter warming in a low oven. Heat half the vegetable oil and half the butter in the skillet over high heat, swirling to coat the sides of the pan. Take care not to let it smoke. Add half the pasta, arranging it a nest. Reduce the heat to medium. Spread the bread crumbs over the center of the pasta nest to within 1½ inches of the edge. Top with the rest of the pasta, completely covering the first layer and enclosing the bread crumbs. Press with the back of a spatula to gently compact the pancake.

Cook over medium to medium-low heat 10 to 13 minutes (checking occasionally for burning), or until the bottom is a deep golden brown. Place a large plate on top of the pancake, and flip it over. Now quickly heat the remaining oil and butter in the pan over high heat, taking care not to let it smoke. Slip the pancake back into the pan, lower the heat to medium, and cook as for the first side. Meanwhile, warm the sugar syrup over medium-low heat.

Serving: Slide the pancake onto the warmed serving platter, and pour the warm sugar syrup over it. Serve hot, cut into small wedges.

Suggestions Wine: A young sweet white: Moscato d’Asti, Asti Spumanti, or Moscato del Trentino.

Menu: Serve after roasted meats, poultry, or game. A Parma-inspired menu begins with small servings of Paola Cavazzini’s Eggplant Torte as a first course, then Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken, a Salad of Mixed Greens and Fennel, and then the torta. As a side dish, have the pancake with January Pork, Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary, or Christmas Capon.

A Chinese Pancake?

Although the idea of pan-fried pasta was not new in Nascia’s time, it was nonexistent in Emilia-Romagna. Nascia was a Neapolitan. Then (as now) Naples had an omelette filled with leftover pasta. The vermicelli in this recipe suggests that he might have brought this dish with him from his home. Although vermicelli had become known throughout Italy by Nascia’s time (and was often a generic name for string pastas), they represent southern cooking rather than that of Parma in the north. The fact that no eggs are used in Nascia’s torta sets loose another thread of speculation. Pan-fried noodles—sometimes stuffed, sometimes not—are frequently made in China. Considering that China possessed a sophisticated pasta culture before Christ, pan-cooked noodle cakes might have been common for centuries before Nascia’s torta. Is it possible that Nascia heard of such a dish from the traders and travelers who crossed his path at the port of Naples, or in Parma’s court? Did he then reinterpret it to suit the tastes of his employers?

Rosewater Maccheroni Romanesca

“A Fare Dieci Piatti di Maccheroni Romaneschi”

This pasta made with rosewater, bread, and sugar, in addition to flour and egg, is a 16-century recipe from Ferrara’s majordomo Christofaro di Messisbugo. More of a curiosity than a dish for our 20th-century palates, the recipe shows how pasta doughs were often flavored at the time. These are the ancestors of today’s pastas of saffron, herbs, and spices. Serve with The Cardinal’s Ragù, or sprinkle on crushed pistachio or toasted almonds along with the cheese, sugar, and spices called for below.

Romanesca, or pasta in the Roman style, is one of the many predecessors of today’s hollow maccheroni. The dough was rolled around batons and cut into short lengths to make one of the earliest recorded tubular pastas in Emilia-Romagna. This variation is an alternative offered by Messisbugo, suggesting the pasta be cut into wide strands.

[Serves 4 as a first course, or garnishes a roast serving 6]

Pasta

1 small white roll (about 2 inches in diameter), trimmed of crust and crumbled

1/3 cup rosewater

2¼ cups plus 6 tablespoons (10 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground is preferred), plus extra as needed

3 tablespoons sugar

Pinch of salt

3 eggs, beaten

6 quarts Poultry/Meat Stock, Quick Stock, or milk

Sauce

6 to 7 tablespoons (3 to 3½ ounces) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 teaspoon rosewater

¼ cup sugar

2/3 cup (2½ ounces) freshly grated Italian Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Generous sprinkling of ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon coarsely ground black pepper, or more to taste

¼ cup shelled pistachio nuts, lightly crushed (optional)

Method Working Ahead: The pasta can be made 1 day ahead. Spread it on towel-lined baskets or baking sheets, and let dry at room temperature.

Making the Dough by Hand: Soak the crumbled roll in the rosewater about 20 minutes. Mound the flour on a work surface, sprinkle it with the sugar and salt, and make a well in the center. Add the eggs and the crumbled roll with its liquid. Working with a fork, stir the eggs and roll together to blend. Then gradually stir flour into the mixture. Use a pastry scraper to mass the dough together. Once a rough dough has formed, knead it 10 minutes, or until smooth and elastic. Wrap it in plastic wrap, and let it rest at room temperature 20 minutes.

Making the Dough in a Food Processor: Combine all the ingredients in the processor and process until smooth. Knead the dough by hand about 10 minutes. Wrap in plastic wrap, and let rest at room temperature 20 minutes.

Shaping the Pasta: Line several large flat baskets with kitchen towels. Thin and stretch the dough by hand or pass it through a pasta machine, as described in Pastas. The dough should be thin enough to clearly see the outline of your hand through it. Cut it into 3/8-inch strips, and spread them on the baskets to dry.

Or, to make the maccheroni as done in Messisbugo’s day, collect some knitting needles or chopsticks to use as dowels. Cut the thinned dough into strips about ¾ inch wide and as long as the dowels. Flour the dowels and wrap the dough strips around them, pinching the edges together. Let dry about 20 minutes, and then make cuts around the dowels, creating hollow pastas about 2 inches long. Dry another 3 to 4 hours, then slip the maccheroni off the dowels. The maccheroni can be dried at room temperature several days.

Cooking the Pasta: Bring the stock or milk to a boil. Drop in the pasta and cook 1 to 5 minutes, depending upon how dry it is. Taste for doneness; it should be firm but tender enough to eat. Drain, and toss the hot pasta with the butter, rosewater, sugar, cheese, cinnamon, and pepper. Sprinkle with the nuts if desired. Serve hot.

Suggestions Wine: A sweet Albana di Romagna Amabile or Moscato d’Asti if you are serving the pasta as a first course. With meats, drink a dry red wine like Sangiovese di Romagna Riserva or Dolcetto d’Alba.

Menu: Serve as in Messisbugo’s day by spreading the sauced maccheroni on a large heated platter. Then set Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary or Christmas Capon on the pasta. Balsamic Roast Chicken is also good with it. Carve the meats on the platter so the juices flavor the pasta. Top with The Cardinal’s Ragù instead of butter, rosewater and spices. Or serve it with the topping described above as a first course before Artusi’s Delight, Rabbit Dukes of Modena, or Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit.

Sweet Tagliarini Tart of Ferrara

Torta di Tagliarini Ferrarese

From the time when pasta with sugar was a sign of high status, this tart combines them with toasted almonds in a sweet crust. It often appeared as small tartlets at the beginning of a Renaissance banquet or with the last course. Serve it today as everyone does in Modena and Ferrara—as a dessert presented to special guests and on important family occasions.

[Serves 8 to 10 as dessert]

Sweet Pastry

1 cup (4 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons (2½ ounces) cake flour

½ cup (3½ ounces) sugar

Pinch of salt

½ teaspoon grated lemon zest

8 tablespoons (4 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled, cut into chunks

3 egg yolks, chilled

1 to 2 tablespoons cold water

1 tablespoon unsalted butter (for greasing pan)

Filling

2 quarts salted water

2 ounces fresh tagliarini, cut as thin as possible, or 3 ounces imported dried fidelini or cappellini

1½ cups (6 ounces) blanched almonds, toasted

1 cup (7 ounces) sugar

3 tablespoons all-purpose unbleached flour

9 tablespoons (4½ ounces) unsalted butter, melted

½ teaspoon almond extract (see Note)

2 tablespoons Strega, Galliano, or liqueur of Moscato

3 tablespoons water

3 egg yolks

6 egg whites

Garnish

1/3 cup powdered sugar

Method Working Ahead: The pastry can be mixed 1 day ahead; wrap it and store in the refrigerator. Bake the tart 8 hours before serving. Tightly wrapped, the tart keeps in the refrigerator several days.

Making the Dough by Hand: Stir the dry ingredients together in a large bowl. Using your fingertips, rub in the butter until the mixture looks like coarse meal with a few large shales of flour-coated butter still intact.

Make a well in the center and add the egg yolks and 1 tablespoon water. Beat the egg yolks and water with a fork until smooth. Then toss with the dry ingredients until everything is moistened. Do not stir or knead because the dough can toughen. Gather the dough into a ball. If it is too dry, sprinkle with the remaining tablespoon of water, toss for a few seconds, and then gather into a ball, wrap, and chill at least 30 minutes.

Making the Dough in a Food Processor: Put the dry ingredients and the lemon zest in a food processor fitted with the steel blade, and blend for a few seconds. Add the butter and process until the mixture resembles coarse meal. Add the egg and 1 tablespoon of the cold water, and process with the on/off pulse until the dough barely gathers into small clumps. Turn the dough out onto a sheet of plastic wrap, gather it into a ball, wrap, and chill at least 30 minutes.

Making the Crust: Sprinkle a work surface with flour. Thoroughly grease a 9-inch layer cake pan with removable bottom and 1¾-inch sides with the tablespoon of butter. Roll out the dough to form a large round about 1/8 inch thick. Make sure the pastry is all of even thickness. Fit into the cake pan, bringing the dough up its sides and neatly trimming it around the pan’s rim. Because of its high sugar content, this pastry breaks easily. Just press it into the pan a piece at a time. Chill about 1 hour.

Preheat the oven to 400°F. Line the crust with foil and weight it with dried beans or rice. Bake 12 minutes. Then remove the liner and weights, prick the bottom of the crust with a fork, and bake another 8 to 10 minutes, or until it is barely beginning to color. Remove from the oven and allow to cool.

Making the Filling: Preheat the oven to 375°F. Have a 10-inch round of parchment paper handy. Bring the salted water to a vigorous boil. Drop in the pasta. Cook fresh pasta only about 10 seconds. Allow 1 minute for dried pasta. It should be tender enough to eat but still quite firm. Drain, rinse under cold water, and shake dry. Spread the pasta out on paper towels.

Coarsely chop one quarter of the almonds. Set aside. Combine the remaining almonds with the sugar and flour in a food processor, and grind to a powder (or use a hand-operated nut grater). Add 6 tablespoons of the melted butter, the almond extract, liqueur, water, and egg yolks to the food processor. Blend thoroughly. Turn into a large bowl. Beat the egg whites to form soft peaks. Lighten the almond mixture by stirring in a quarter of the whites. Then gently fold the rest of the whites in, blending thoroughly but keeping the mixture light. Slather half the filling over the bottom of the crust. Spread half the pasta over it. Then top with the remaining filling. Sprinkle the reserved almonds over the filling, top with the rest of the pasta, and drizzle with the remaining melted butter.

Baking the Tart: Lightly cover the tart with a round of parchment paper, and bake 20 minutes. Uncover and bake another 30 to 35 minutes, or until a knife inserted about 2 inches from the edge comes out clean. Cool the tart on a rack.

Serving: Slip off the side of the pan, and serve at room temperature. Sift a generous dusting of powdered sugar over the tart just before presenting.

Suggestions Wine: From Emilia-Romagna, a sweet white Bianco di Scandiano. From other parts of Italy, the Piedmont’s Caluso Passito or Malvasia delle Lipari from Sicily. Although heresy to Italian purists, France’s Château d’Yquem Sauternes complements the tart splendidly when fine Italian dessert wines are not available.

Menu: Serve after dishes from the Modena/Ferrara area, such as Balsamic Roast Chicken, Rabbit Dukes of Modena, Artusi’s Delight, Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel, or Riccardo Rimondi’s Chicken Cacciatora. For a lighter menu, serve a main dish of tagliatelle with Meat Ragù with Marsala, Risotto of Baby Artichokes and Peas, or Risotto of Red Wine and Rosemary, then the tart.

Cook’s Notes Almond Extract: Almond extract replaces the traditional bitter almonds, used for centuries to accent almond dishes. Bitter almonds, which can form harmful prussic acid, are banned in the United States. If available, the kernel found inside a peach or apricot pit can be toasted and ground with the almonds to attain a bitter almond flavor.

Idealized portrait of Lucrezia Borgia by Bartolomeo Veneto

Il Collectionista, Milan

The Misunderstood Borgia

The infamous Lucrezia Borgia is inseparable from the Sweet Tagliarini Tarts found in every Ferrara pastry shop. The Ferrarese speak of the woman as though she has just left the room. Affection for her has not diminished in the four and a half centuries since her death. Few believe she murdered her first two husbands. Everyone, from the lady waiting on you in the pastry shop to the town’s leading businessmen, explains how misunderstood she was, how her father and brother were the evil ones. Besides, even if some suspicion might have clouded her earlier marriage, once she settled down in Ferrara with her third husband, Alfonso d’Este, heir to the Este dukedom, all was well. As Duchess of Ferrara, she became a patroness of the arts, famous for her gentleness, beauty, and keen intelligence.

In 1502, the about-to-be-married Lucrezia entered Ferrara with such a lavish show of wealth that even the Este, masters of appearing richer than they actually were, were impressed. Five years were needed to calculate the value of her dowry, which included whole towns as well as jewels, furnishings, artworks and gold. Ferrara lore claims that Sweet Tagliarini Tart was created by Este court cooks for Lucrezia’s wedding feast, its tangled topping of golden pasta strands a tribute to Lucrezia’s blond hair. Different versions of the tart are found in Modena and across the Po River in Mantua, which shared much with Ferrara during the centuries of Este rule.

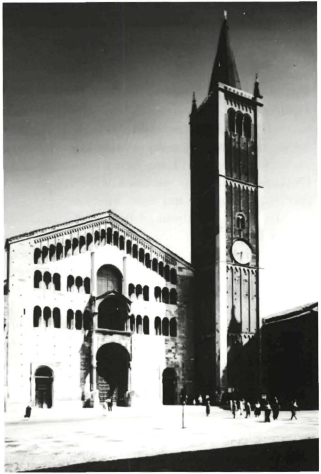

Parma’s Romanesque duomo, Saint Mary of the Assumption