DESSERTS

Cakes, Tarts and Pastries, Spoon Sweets, and the “Keeping Cakes” of Winter

This panorama of Emilia Romagna’s desserts spans both time and distance. It does not pretend to encompass the wealth of the region’s sweets, but rather is a sampling of each area and period. Included here are 400 years of court food, beginning in the 1500s with Cardinal d’Este’s Tart and weaving through the centuries to the contemporary Frozen Hazelnut Zabaione with Chocolate Marsala Sauce. I have borrowed as well from the vast collection of sweets marking feast days and festivals. And there are home dishes, their origins ranging from mountain villages to the farms of the Po River plain. Some are country desserts still baked in the hot coals of kitchen hearths, while others were created in the modern stainless steel kitchens of city restaurants.

Desserts in Emilia-Romagna possess almost as much diversity as do her pastas. The simplest of sweets, like fresh melon with balsamic vinegar and mint, exist side by side with the unrestrained excess of a frozen mousse of espresso, mascarpone cheese, and cream. The same pastry shop may produce the homey Ciambelle cake and sophisticated Duchess of Parma Torte. Desserts fall into several categories. Dolci is the all-inclusive term for sweets. A torta can be a cake, a tart, or a pudding in the shape of a cake.

“Keeping cakes” of winter is my own phrase for the spiced cakes of Christmas, baked in autumn and mellowed until the holidays. They are part of a category of sweets meant for long storage or maturing (dolci di lunga conservazione). Jams, conserves, cookies, candies, grape syrup, and liqueurs all fall into this group. Spoon sweets (dolci al cucchiaio) are literally spoonable custards and creams. For me, fruit dishes are part of this category, as are frozen desserts.

Chestnut dishes are under yet another heading. Although there are only three, they represent rich traditions from the hills and mountains of the region. These nuts were the flour, sweetener, and substance of many sweets in the past.

With each recipe you will find information on its traditions and ideas for serving the dish today. The menu suggestions at the end of each recipe get down to specifics, explaining how to serve the sweets with the rest of the dishes in this book.

A Note on Pastry: The tarts in this chapter share a similar pastry, a butter/sugar dough called pasta frolla. Some tarts demand a crust with more butter or sugar, and some less. In Nonna’s Jam Tart, there is yet another possible interpretation of the pastry. The butter and sugar are whipped to a fluff with flour folded in later, creating a shortbread-style crust that is light and crisp.

Shorter, sweeter crusts may break apart as you transfer them to the tart pan. But remember, no one sees the bottom of your dessert. As long as the thickness of the crust is even for proper baking, there is nothing to worry about. Just press the pieces into the pan, joining the edges by pinching them together. These fragile crusts reward with melt-in-the-mouth tenderness.

Torta Barozzi

A sensational specialty, made only in the castle town of Vignola outside Modena, Torta Barozzi is to chocolate cake what a diamond is to zircon. It looks like yet another flourless chocolate cake, but one mouthful banishes any sense of the mundane. This is a chocolate essence, moist and fudgy, with secret ingredients known only to the baker. Serve the rich cake cut in small wedges, and do tell the story of Modena’s obsession with a seemingly conventional chocolate cake.

[Makes 1 cake, serving 6 to 8]

½ cup (2 ounces) blanched almonds, toasted

2 tablespoons confectioner’s sugar

4 tablespoons cocoa (not Dutch process)

1½ tablespoons unsalted butter

3 to 4 tablespoons all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

8 tablespoons (4 ounces) unsalted butter, at room temperature

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons (4 ounces) sugar

4½ tablespoons smooth peanut butter

4 large eggs, separated

6 ounces bittersweet chocolate, melted and cooled

1 ounce unsweetened chocolate, melted and cooled

2½ tablespoons instant espresso coffee granules, dissolved in 1 tablespoon boiling water

1½ teaspoons dark rum

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

Decoration

1 tablespoon cocoa

½ tablespoon confectioner’s sugar

Method Working Ahead: The Barozzi can be baked ahead and has admirable keeping qualities. It may be slightly better tasting in the first 24 hours after baking, but the cake keeps all its flavor when tightly wrapped and stored in the refrigerator up to 3 days. It freezes well 2 months. Serve at room temperature.

Making Almond Powder: Combine the almonds, 2 tablespoons confectioner’s sugar, and 3 tablespoons cocoa in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. Process until the almonds are a fine powder.

Blending the Batter: Butter the bottom and sides of an 8-inch springform pan with the 1 tablespoon of butter. Cut a circle of parchment paper to cover the bottom of the pan. Butter the paper with ½ tablespoon butter and line the pan with it, butter side up. Use the 3 to 4 tablespoons flour to coat the entire interior of the springform, shaking out any excess. Preheat the oven to 375°F, and set a rack in the center of the oven. Using an electric mixer fitted with the paddle attachment or a hand-held electric mixer, beat the butter and sugar at medium speed 8 to 10 minutes, or until almost white and very fluffy. Scrape down the sides of the bowl several times during beating. Beating the butter and sugar to absolute airiness ensures the torta’s fine grain and melting lightness. Still at medium speed, beat in the peanut butter. Then beat in the egg yolks, two at a time, until smooth. Reduce the speed to medium-low, and beat in the melted chocolates, the dissolved coffee, and the rum and vanilla. Then use a big spatula to fold in the almond powder by hand, keeping the batter light.

Whip the egg whites to stiff peaks. Lighten the chocolate batter by folding a quarter of the whites into it. Then fold in the rest, keeping the mixture light but without leaving any streaks of white.

Baking: Turn the batter into the baking pan, gently smoothing the top. Bake 15 minutes. Then reduce the oven heat to 325°F and bake another 15 to 20 minutes, or until a tester inserted in the center of the cake comes out with a few streaks of thick batter. The cake will have puffed about two thirds of the way up the sides of the pan. Cool the cake 10 minutes in the pan set on a rack. The cake will settle slightly but will remain level. Spread a kitchen towel on a large plate, and turn the cake out onto it. Peel off the parchment paper and cool the cake completely. Then place a round cake plate on top of the cake and hold the two plates together as you flip them over so the torta is right side up on the cake plate.

Serving: Torta Barozzi is moist and fudgy. Just before serving, sift the tablespoon of cocoa over the cake. Then top it with a sifting of the confectioner’s sugar. (Or for a whimsical decoration, cut a large stencil of the letter “B” out of stiff paper or cardboard. Set it in the center of the cake before dusting the entire top with the confectioner’s sugar. Carefully lift off the stencil once the sugar has settled.) Serve the Barozzi at room temperature, slicing it in small wedges.

Suggestions Wine: In Vignola, homemade walnut liqueur (Nocino) is sipped with the Barozzi. Here, the black muscat-based Elysium dessert wine from California does well with the cake’s intense chocolate.

Menu: Serve after Modena dishes such as Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, Beef-Wrapped Sausage, Balsamic Roast Chicken, and Rabbit Dukes of Modena, or after light main dishes and first courses.

Cook’s Notes Chocolate: Use a chocolate rich in deep fruity flavors, such as Tobler Tradition or Lindt Excellence.

Peanut Butter: Peanut butter is the surprise ingredient in the cake, and an important one. I use creamy Skippy, but no doubt other brands work well too.

Whipped Cream: Although not served this way in Vignola, the Barozzi is superb topped with dollops of unsweetened whipped cream. Count on whipping 1 cup of heavy cream to serve 6 to 8.

“It’s All There on the Box”

Cracking the code of Torta Barozzi is Modena’s favorite food game. For decades local cooks have tried to unravel its mystery, without success. When a Modenese dinner party gets dull, ask about Torta Barozzi and settle back. The heat of the debate will warm you for the rest of the evening. Eugenio Gollini invented the cake in 1897 at his Pasticceria Gollini in Vignola. The cake commemorated the birthday of Renaissance architect Jacopo Barozzi, a native son of Vignola who invented the spiral staircase. Today Gollini’s grandsons, Carlo and Eugenio, still make Barozzi at the same pasticceria. Its recipe is secret, although its ingredients are stated on the cake’s box. Family members have sworn never to reveal nor change the formula. But Eugenio Gollini smiles serenely when he tells you it is all there in plain sight.

Gollini offered no clue of how peanuts—a startling and definitely non-Italian ingredient—became part of the cake. I speculate that late 19th-century cooks considered these nuts, brought from Africa, to be exotic and intriguing. Perhaps in experimenting with them, the elder Gollini discovered how good they are with chocolate. Then he might have found that peanuts puréed into peanut butter ensured a smoother and even more melting Torta Barozzi Historian Renato Bergonzini explained why the people of Vignola believe the cake’s secret eludes discovery: “Barozzi left the last step of his spiral staircase unfinished. No one knows why, and no one would presume to finish it. To imitate the torta is like trying to finish Barozzi’s staircase: impudent and foolish. Only the master himself can complete his work.” I confess to both impudence and foolishness, but also to success. This recipe comes tantalizingly close to the original.

Torta di Riso

The food of grandmothers, this baked rice pudding is scented with citron or almond. Baking burnishes it to a glowing gold and makes it firm enough to be sliced like a cake. Although made throughout the region, this rendition from Modena was shared by Catherine Piccolo of the Modena/St. Paul, Minnesota, Sister City Committee. This pudding is the dessert served after Sunday dinner in farmhouses on the Po River plain. It is pulled from the cold pantry for special guests, and is especially favored around Easter time.

[Serves 8 to 10]

3½ cups milk

1 cup (7 ounces) imported Superfino Arborio or Roma rice

1¼ cups (8¾ ounces) sugar

1½ tablespoons unsalted butter

5 large eggs, beaten

2 teaspoons grated lemon zest

¾ cup (4 ounces) high-quality candied citron, finely diced, or ¾ cup (3 ounces) blanched almonds, toasted and coarsely chopped

Method Working Ahead: The pudding can be made 1 day ahead. Wrap the dish and store it in the refrigerator until 1 hour before serving. It is equally good served warm from the oven or chilled.

Cooking the Rice: In a heavy 3- to 4-quart saucepan, combine the milk and rice. Bring to a gentle bubble over high heat. Turn the heat down to low, cover tightly, and cook 20 to 25 minutes at a very slow bubble. Stir occasionally to check for sticking. When the rice is tender but still a little resistant to the bite (it will be a little soupy), stir in the sugar. Turn it into a bowl and allow it to cool.

Mixing and Baking the Torta: Butter a 9-inch springform pan with the 1½ tablespoons butter. Preheat the oven to 350°F. Stir the eggs, lemon zest, and citron or almonds into the cooled rice. Turn into the pan, and bake 55 to 65 minutes, or until a knife inserted 2 inches from the edge comes out clean.

Serving: To serve at room temperature, cool the pudding to room temperature on a rack, and then unmold. Refrigerate if you will be holding it for longer than 2 hours. Slice into narrow wedges. Serve warm by reheating the pudding in its mold at 325°F about 20 minutes. Then release the sides of the pan and set the torta on a round plate.

Suggestions Wine: Usually no special wine accompanies the torta, just a little of the wine taken with dinner. On special occasions, I like small glasses of a chilled dry Marsala or a little Vin Santo from Tuscany.

Menu: Have a few Garlic Crostini with Pancetta as antipasto. Follow with Ferrara’s Soup of the Monastery as the main dish, and then the torta. The pudding is also a fine dessert after Riccardo Rimondi’s Chicken Cacciatora or Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel.

Cook’s Notes Citron and Substitutions: High-quality candied citron tastes sweet/tart and spicy. You can find it in large chunks in specialty food stores and Italian markets around Christmas time. If unavailable, substitute ¾ cup coarsely chopped candied pineapple, diced fine and blended with 2 teaspoons lemon juice, 1/8 teaspoon ground cinnamon, and a pinch of freshly ground black pepper. This substitution is successful in this dish, but not always in others calling for citron.

My Own Variation: I like to pour hot Fresh Grape Syrup over chilled slices of the torta.

Bensone di Modena

“Bensone always stains the tablecloth” declares an old Modena saying. Dunking the crumbling cake in glasses of sweet wine is a favorite way of eating Bensone. The cake breaks up in the wine and is eaten with a spoon.

Simple ingredients and even simpler technique create the S-shaped cake. Its crust is craggy, and the melting sugar on top looks like molten crystal. Bensone is never too sweet. It looks and tastes homemade—like a sweet, slightly crumbly biscuit.

[Makes 1 cake, serving 8 to 10]

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

2 cups (8 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

2 cups (8 ounces) cake flour

Pinch of salt

¾ teaspoon baking soda

¾ teaspoon baking powder

1 cup (7 ounces) sugar

2 teaspoons grated lemon zest

12 tablespoons (6 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into chunks

3 large eggs, beaten

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

¼ cup milk

1½ tablespoons pearl sugar (see Note) or granulated sugar

Method Working Ahead: The cake is best eaten within several hours of baking. It will keep, tightly wrapped, at room temperature 2 days.

Blending the Dough: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Grease a large baking sheet with the 1 tablespoon butter. Set a rack in the center of the oven. Make the cake in the easiest and most traditional way—by hand. Put all the dry ingredients (including the lemon zest but not the pearl sugar) in a shallow bowl. Blend them with your hands or with a fork. Rub the chunks of butter into the dry ingredients, using your fingertips, until the mixture resembles coarse meal. Make a well in the middle of the mixture, and add all the liquids. Stir them with a fork to blend. Then gradually work in the dry ingredients, using a tossing motion rather than stirring to blend the dry and moist ingredients together. Thoroughly moisten the dough, but do not worry if it is lumpy. Avoid beating the dough, as that toughens it. The dough should be lumpy, sticky, and moist.

Shaping the Cake: Sprinkle a little flour on a work surface and turn the dough out on top of it. Lightly flour your hands. Protect the dough from being overworked by just patting and nudging it into shape. Create a long, slightly flattened cylinder 3 to 4 inches wide and about 1 inch thick. Twist it into an S shape. Transfer it to the baking sheet, and sprinkle it with the 1½ tablespoons sugar. (Some Modenese cooks first brush the dough with 3 tablespoons milk.) Slip the baking sheet into the oven.

Baking and Serving: Bake 25 minutes. Then lower the heat to 250°F and bake another 25 minutes, or until a tester inserted in the center comes out clean. Transfer the Bensone to a rack. Either let it cool about 20 minutes and serve it warm, or let it cool for about 1 hour and serve it at room temperature. Cut it into ½-inch-thick slices.

Suggestions Wine: The Piedmont’s Moscato d’Asti or Freisa di Chieri Amabile is a fine wine for sipping and dunking with the Bensone. In Modena it would be a fresh and sweet Lambrusco Amabile.

Menu: This is a simple, homey dessert, excellent after country dishes like Maria Bertuzzi’s Lemon Chicken, Grilled Beef with Balsamic Glaze, Herbed Seafood Grill, Seafood Stew Romagna, or Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel. Often Bensone is taken between meals with coffee.

Cook’s Notes Pearl Sugar: These pea-size pellets of white sugar are found in specialty food stores.

Ciambelle con Marmellata

Bake fruit jam in the center of Modena Crumbling Cake and you have a sweet called Ciambelle in Emilia-Romagna. This long, low cake tastes like a cross between a soft filled cookie and a sweet biscuit.

Ciambelle embodies the simple, direct quality of the homemade cakes of generations ago. Made by almost every grandmother in Emilia-Romagna, it is also found in every pasticceria. The cake greets youngsters after school, feeds neighbors dropping in for midmorning coffee, and makes a comforting finale to family dinners. In this country I take it on picnics and to potluck suppers, and serve it at casual dinners and buffets.

[Makes 1 cake, serving 6 to 8]

Dough

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

1 cup (4 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

1 cup (4 ounces) cake flour

Pinch of salt

¼ teaspoon baking powder

¼ teaspoon baking soda

½ cup sugar

1 teaspoon shredded lemon zest

6 tablespoons (3 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into pieces

1 large egg

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

3 tablespoons milk

Filling

¾ cup Homemade Tart Jam or high-quality store-bought plum, apricot, cherry, or strawberry preserves

Decoration

2 teaspoons pearl sugar (see Note, Desserts) or granulated sugar

Method Working Ahead: Although the jam cake is best eaten within several hours of baking, it keeps 2 days if tightly wrapped and stored in the refrigerator.

Blending the Dough: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Grease a baking sheet with the tablespoon butter, and set an oven rack in the center of the oven. Make the jam cake in the easiest and most traditional way—by hand. Put all the dry ingredients for the dough, including the lemon zest, in a shallow bowl. Blend them thoroughly with your hands or with a fork. Rub the butter into the dry ingredients, using your fingertips, until the mixture resembles coarse meal. Stir the egg, vanilla, and milk together. Make a well in the middle of the dry ingredients, and add the liquids. Gradually work in the dry ingredients, tossing them with a fork rather than stirring. The idea is to thoroughly moisten the dough but not beat it, as that makes it tough. Help with your hands. The dough should be lumpy, sticky, and moist.

Shaping and Filling the Dough: Generously flour a work surface, and turn the dough out onto it. Lightly flour your hands. Pat the dough out to form a rectangle about 8 inches wide and 13 inches long. Dab the jam down the center, in a ribbon about 2 inches wide. Fold the two flaps of pastry lengthwise over the filling, overlapping slightly. Pinch the seam together down the length of the cake. Pinch the ends together so the jam can’t ooze out during baking.

Baking and Serving: Transfer the pastry to the baking sheet, and sprinkle with the 2 teaspoons sugar. Bake 25 minutes. Reduce the heat to 250°F and bake another 25 minutes. Serve the Ciambelle warm or at room temperature. Cut it into slices about ½ inch thick, and arrange them on a platter.

Suggestions Wine: A cool white Moscato d’Asti or a dry Marsala Superiore or Ambra tastes fine with the Ciambelle. Many Emilians dip it in a local Lambrusco. “La Monella” from the Piedmontese vineyard of Braida di Giacomo Bologna is a fine stand-in for good Lambrusco.

Menu: Serve after Balsamic Roast Chicken, Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, January Pork, Artusi’s Delight, Beef-Wrapped Sausage, or Lamb, Garlic, and Potato Roast.

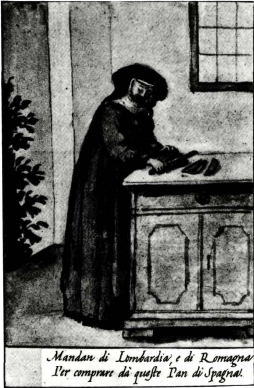

Hawker selling ciambelle in Bologna’s marketplace. Engraving by Giovanni M. Tamburini, from a picture by Francesco Curti, circa 1640.

Casa di Risparmio, Bologna

Will the Real Ciambelle Please Stand?

Codifying Ciambelle defies all logic. It translates as “ring cake,” yet this traditional recipe is for a long loaf that looks like a flattened baguette. In pastry shops throughout the region, you can find long loaves (with or without a jam filling) sitting side by side with the same pastry baked into rings. Even more confounding, some are like pound cakes while others resemble sweet buttery biscuits. Each is called Ciambelle. Seventeenth-century Bolognese engravings show street vendors hawking Ciambelle rings—they carried them strung like doughnuts on long poles. Early recipes describe sweet Ciambelle like this recipe, as well as savory ones baked without sugar. Every part of the region has its favorite version, and the name changes according to where you happen to be. What is the true Ciambelle? It is the one you are eating at that particular moment.

Torta Duchessa

Created in 1985 by pastry chefs Ugo Falavigna and Dino Paini, this torte honored the winners of Parma’s Maria Luigia International Journalism Prize. If I die and go to heaven, I know I will be served this cake as my ultimate reward. Layers of hazelnut meringue separate two buttercreams, one a zabaione scented with Marsala, the other dark chocolate with rum and espresso.

[Serves 8 to 12]

Chocolate Buttercream

8 egg yolks

1 cup (7 ounces) sugar

6 tablespoons very strong brewed espresso

¼ cup dark rum

1 ounce unsweetened chocolate, melted

4 ounces bittersweet chocolate, melted

1 cup plus 6 tablespoons (11 ounces) unsalted butter, at room temperature

Method Working Ahead: The chocolate buttercream can be made 5 days ahead. Store it, covered, in the refrigerator. Bring it to room temperature before spreading on the meringues.

Making the Chocolate Buttercream: In a metal electric mixer bowl or a medium metal bowl that works well with a hand-held electric mixer, combine the egg yolks, sugar, coffee, and rum. Whisk by hand over a pan of boiling water (not letting the bowl touch the water) 5 to 8 minutes, or until the custard is thick. It should read between 160° and 165°F on an instant-reading thermometer.

Once thickened, set the custard in its mixing bowl on the mixer, and beat it at medium speed 8 minutes, or until cool. If using a hand-held mixer, beat the same way. Then beat in the melted chocolates. Keeping the mixer at medium speed, beat in the butter, 1 tablespoon at a time, beating each addition until smooth. Scrape down the sides of the bowl from time to time. The final buttercream should be silken and fluffy. If it is too soft, chill 20 minutes and then beat to fluff it up. Keep the buttercream at room temperature if you will be using it within a couple of hours. Otherwise, cover and refrigerate.

Meringues

2 to 3 tablespoons unsalted butter

4 tablespoons all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

2 cups (8 ounces) hazelnuts, toasted and skinned

¾ cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

3 tablespoons all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

7 large egg whites (1 cup)

¼ teaspoon cream of tartar

Method Working Ahead: The nuts can be ground 1 day ahead. Once the whites are beaten, immediately fold in the nuts and bake. The baked and cooled meringues can be left on a rack at room temperature in a dry place 1 day before assembling the torte. If possible, avoid making meringues on humid days.

Making the Meringues: Butter and flour three 9-inch round cake pans. Cut circles of parchment paper to fit the bottom of each pan, and set them in place. Preheat the oven to 350°F. Grind the nuts with half the sugar, and all the flour in a food processor. The mixture should be very fine but not turned to nut butter. Beat the egg whites with the cream of tartar to form soft peaks. Gradually beat in the remaining sugar, and beat to stiff peaks. Using a large spatula, fold in the nut mixture, keeping the meringue light. Spread the mixture in the pans. Bake the meringues 22 minutes. They should be golden and almost hard, but still have a little spring when pressed. If the weather is humid or the meringues are still soft, they may need another 5 minutes of baking. Cool them in the pans on a rack 1 hour. Then run a knife around the inside of the pans to loosen the meringues. Gently turn the layers out of their pans. Carefully peel away the parchment paper. Trim any ragged edges so all the layers are the same size. Leave the meringues on a rack at room temperature until ready to use.

Zabaione Buttercream

5 egg yolks

7 tablespoons dry Marsala

¼ cup sugar

1 teaspoon dark rum

12 tablespoons (6 ounces) unsalted butter, at room temperature

Method Working Ahead: The flavors of this cream are more fragile than the chocolate cream. So store it for no more than 24 hours, covered and refrigerated, before assembling the torte. Bring it to room temperature before spreading it on the meringues.

Making the Zabaione Buttercream: Use a free-standing or a hand-held electric mixer for this buttercream. First, by hand whisk together the egg yolks, Marsala, sugar, and rum in the metal bowl of an electric mixer or a medium metal bowl that works well with a hand-held mixer. Set the bowl over a pan of boiling water, taking care that the water does not touch the bowl. Whisk 4 to 5 minutes, or until thickened. The custard should read about 160° to 165°F on an instant-reading thermometer.

Remove from the heat, and, with a mixer, whip at medium speed 8 minutes, or until cooled to room temperature. Keeping the mixer at medium speed, beat in 9 tablespoons of the butter, 1 tablespoon at a time, beating each addition until smooth. The buttercream may seem too soft, but do not worry. Add the last 3 tablespoons all at once, and beat until smooth. The buttercream should fluff up. If not, chill about 20 minutes and then beat until fluffy. Keep the buttercream at room temperature if you will be using it within a couple of hours. Otherwise, cover and refrigerate.

Chocolate Glaze

2½ ounces bittersweet chocolate

2½ tablespoons unsalted butter

2 teaspoons light corn syrup

Method Working Ahead: The glaze can be made several hours ahead and rewarmed over hot water. Since its sheen dims with refrigeration, it is best to leave the glazing for shortly before serving. Spread the glaze over the cold torte about 1 hour before presenting it at the table.

Making the Glaze: Combine all the ingredients in a small bowl set over boiling water or a double boiler. Stir until it is a smooth cream. Set aside.

Assembling the Torte: Protect the borders of a flat round cake plate by covering them with 4 sheets of wax paper. Dab about 1 tablespoon of the chocolate buttercream in the center of the plate to hold the first layer of meringue in place. Place one meringue layer in the center of the plate. Spread chocolate buttercream ½ inch thick over the meringue layer, making it a little higher around the edges. (There will be enough left to frost the sides of the torte and decorate the top.)

Set the second meringue layer upside down on the buttercream. Press gently so it sits flat. Slather all the zabaione buttercream over the meringue, spreading it a little higher near the edges. Top with the last meringue, again upside down. Then, using your palms, press the center gently to make sure the layer is straight, not dipping down or bowing up. Firm the torte by chilling it in the refrigerator about 30 minutes. Using a long metal spatula, cover the sides of the torte with a thin coating of chocolate buttercream. Spoon the remaining chocolate buttercream into a pastry bag fitted with a wide serated tip. Pipe an undulating border around the outer edge of the torte’s top layer. (There will be about ½ cup buttercream left over.) Refrigerate the torte at least 1 hour before topping it with the glaze.

Glazing and Serving: About 1 hour before serving, remove the torte from the refrigerator and carefully spoon the glaze on its top. Spread the glaze with the back of the spoon so it flows up to the buttercream border, completely covering the meringue. The glaze will harden to a bright sheen on the cold meringue. (If refrigerated, the sheen dims.) Using a wet knife, slice the torte while it is still cold. Then let it come to room temperature. To serve, slip the thin slices out of the cake and onto dessert plates.

Suggestions Wine: Usually chocolate is not accompanied by wine in Italy, but California’s Elysium dessert wine is a fine match to the torte.

Menu: Reserve the torte for special occasions. Serve it after simple but elegant dishes like Christmas Capon, Pan-Roasted Quail, Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, Rabbit Dukes of Modena, Herbed Seafood Grill, or Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary.

Cook’s Notes Chocolate: My first choice is Tobler Tradition, with Lindt Excellence second.

Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma

The Duchess of Parma

There is only one. Although many women have held the title, in Parma when you say “Duchess of Parma,” everyone knows you are referring to Marie Louise of Austria. She was the city’s most beloved ruler, and her name is on everything suggesting refinement and excellence.

As princess of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and wife to Napoleon, she was forced to make a choice. She could either go into exile with Napoleon on Elba or rule Parma with the assistance of Austrian general Adam Albert Neipperg. A dashing military man, Neipperg was tall, intelligent, and strikingly handsome. The black patch over his eye only added excitement. Historical gossip claims they were lovers even before Marie Louise had to decide between Parma and Napoleon. She chose Parma, sharing her reign with Neipperg, and the next 30 years were some of the brightest in Parma’s history. The city’s elegant neoclassic opera house is one tangible legacy of Marie Louise’s era. Some music experts say its audiences are even more demanding of singers than La Scala.

Another legacy is the city’s identifying color, “Parma yellow.” This soft golden yellow tinged with orange is always matte and velvety, never hard and flat. The opera house is Parma yellow, as are many of the town’s buildings. The color is a melding of the Hapsburg yellow of Marie Louise’s family crest and the yellow of France’s Bourbon ruling family, who held Parma during the 18th century. (Modena has its yellow, similar to Parma’s, stemming from Modena’s own long relationship with Austria.) Pastry shops share another Marie Louise legacy: influences from France and Austria that make Parma pastries more refined and intricate than most.

Marie Louise (or Maria Luigia as she is known in Parma) is still a presence in the city. Her picture is found in shops, homes, and restaurants almost as often as portraits of native son Giuseppe Verdi. The portrait you see most often is the one I like the least. In it she is young, her long narrow head looks overbred, and the blue eyes are bland. In a later portrait, painted when she was in her fifties, she is far more compelling. Experience, intelligence, and passion speak out from the pale face. The jaw and cheekbones are strong, the eyes glow. This is a woman who could rule a duchy, a duchess worthy of Parma.

Crostata di Mandorle

This tart from both Emilia and Romagna is a big circle of shortbread covered with caramelized almonds and tasting of lemon and almonds.

[Makes 1 tart, serving 8 to 10]

Pastry

1 cup (4 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

1 cup (4 ounces) cake flour

6 tablespoons (2½ ounces) sugar

Shredded zest of 1 small lemon

8 tablespoons (4 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into chunks

1 large egg, beaten

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

Filling

¼ cup water

¾ cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

Shredded zest of 1 small lemon

5 tablespoons (2½ ounces) unsalted butter

¼ cup heavy cream

3 tablespoons Anisette liqueur

1/3 cup water

3 cups (12 ounces) whole blanched almonds, toasted and coarsely chopped by hand

½ teaspoon almond extract

2 tablespoons Anisette liqueur

Method Working Ahead: The pastry shell can be baked 1 day ahead. The tart keeps well, tightly wrapped, in the refrigerator 2 to 3 days. Serve it at room temperature.

Making the Pastry in a Food Processor: Combine the dry ingredients, including the lemon zest, in a processor fitted with the steel blade. Blend 10 seconds. Then add the butter and process until the mixture looks like coarse meal. Add the egg and process only until the dough is crumbly. Gather it into a ball, wrap, and chill 30 minutes or overnight.

Making the Pastry by Hand: Stir the dry ingredients, including the lemon zest, together in a shallow bowl. Rub in the butter, using your fingertips or a pastry cutter, until there are just a few shales of solid butter left. Using a fork, toss in the egg to barely moisten the dough. Gather it into a ball, wrap, and chill 30 minutes or overnight.

Preparing the Crust: Preheat the oven to 400°F. Use the tablespoon of butter to grease an 11-inch fluted tart pan with removable bottom. Generously flour a work surface. Roll out the pastry to form a 14-inch round about ¼ inch thick (the pastry and filling are of equal thickness in this tart). Fit it into the tart pan. The dough is fragile, so do not worry if it breaks, just press the pieces together in the pan. No one sees the bottom of a tart shell. Prick it with a fork and chill 30 minutes. Line the crust with foil and weight it with dried beans or rice. Bake 10 minutes. Then remove the liner and weights, turn the temperature down to 350°F, and bake another 5 to 8 minutes, or until pale gold. Cool on a rack.

Making the Filling: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Combine the water and sugar in a 3-quart saucepan. Cook over medium heat 4 to 6 minutes, or until clear, brushing down the sides of the pan with a brush dipped in cold water. Raise the heat to high and bubble fiercely 9 to 12 minutes, or until the syrup is honey colored. Remove the pan from the heat, and stir in the lemon zest and butter. Once the butter has melted, stir in the cream, liqueur, 1/3 cup water, and almonds. Set the pan over high heat a few seconds to dissolve the caramel. Stir in the almond extract, and pour the filling into the pastry shell.

Baking and Serving: Bake 30 minutes (do not worry when the filling bubbles and seethes). Just before removing it from the oven, brush with the 2 tablespoons liqueur. Cool the tart on a rack. Slice it in wedges for serving.

Suggestions Wine: From the region, have a sweet red Cagnina of Romagna or the Veneto’s white Torcolato. Or have small glasses of the same anise liqueur flavoring the tart.

Menu: The tart makes a fine finale to a menu featuring Tagliatelle with Caramelized Onions and Fresh Herbs, Spaghetti with Anchovies and Melting Onions, Mardi Gras Chicken, Lamb, Garlic, and Potato Roast, Fresh Tuna Adriatic Style, or Pan-Roasted Quail.

Ugo Falavigna’s Apple Cream Tart

Torta di Mele Ugo Falavigna

Ugo Falavigna, of Parma’s Pasticceria Torino, sautés lemon-scented apples, spreads them in sweet pastry, and naps the fruit in silky custard before baking. In this gentle adaptation of his recipe, I have encouraged the apples to absorb even more of the lemon, bringing out the fresh taste of the fruit and making the custard seem creamier. Include the tart in any menu made without lemon, but especially when pasta and ragù are offered as a main dish.

[Makes 1 tart, serving 6 to 8]

Pastry

¾ cup (3 ounces) cake flour

¾ cup (3 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

6 tablespoons (2½ ounces) sugar

Generous pinch of salt

6 tablespoons (3 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into chunks

1 large egg yolk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 to 2 tablespoons cold water

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

Apples

5 medium Granny Smith apples

Juice of 1 large lemon

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1½ tablespoons sugar

Custard

1 cup milk

1 vanilla bean, split lengthwise

6 tablespoons sugar

2 large eggs

2 large egg yolks

Garnish

¼ cup confectioner’s sugar (optional)

Method Working Ahead: The pastry and custard can be made 1 day ahead. Cover and refrigerate them until you are ready to assemble the tart. The apples need to marinate in the lemon juice 3 to 4 hours. Serve the tart within 8 hours of baking.

Making the Pastry by Hand: Blend the dry ingredients together in a bowl. Using a pastry cutter or your fingertips, cut in the butter until only a few shales of butter are visible. Using a fork, toss in the egg yolk, vanilla, and 1 tablespoon water, moistening the pastry only enough for it to hold together when gathered into a ball. If it is too dry, sprinkle with another tablespoon of water and toss. Do not stir or knead.

Making the Pastry in a Food Processor: Combine the dry ingredients in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. Add the butter and process 30 seconds, or until the mixture looks like coarse meal. Add the egg yolk, vanilla, and 1 tablespoon water. Process with the on/off pulse until the pastry begins to gather in small clumps. If it is dry, sprinkle with another tablespoon of water and process.

Chilling and Baking Pastry: Gather the dough into a ball, wrap it in plastic wrap, and chill 30 minutes. Meanwhile, use the ½ tablespoon of butter to grease a 9-inch tart pan with removable bottom. Sprinkle a work surface generously with flour. Roll out the dough to about 1/8 inch thick, and fit it into the tart pan. Chill at least 30 minutes. While the crust is chilling, preheat the oven to 400°F. Line the chilled pastry with aluminum foil, and weight it with dried beans or rice. Bake for about 10 minutes. Lift out the weights and liner. Continue baking another 5 minutes, or until it looks dry but not browned. Cool on a rack.

Sautéing the Apples: Peel and core the apples. Cut them into ½-inch-thick wedges, and toss them in a bowl with the lemon juice. Let the apples macerate with the lemon juice 3 or 4 hours at room temperature. Heat the 3 tablespoons of butter in a large Sauté pan over medium-high heat. Turn the heat up to high as you add the apples. You want to cook off the apples’ moisture without reducing them to mush. Sauté 5 to 6 minutes, or until they have given up their moisture and started to brown. Keep turning the pieces with a wooden spatula. Sprinkle with the sugar, and remove from the heat. Cool the apples by spreading them out on a large platter.

Making the Custard: Scald the milk in a 3-quart saucepan by heating it with the vanilla bean until bubbles appear around the edge of the pan. Remove it from the heat and cool for about 15 minutes. In a medium bowl, whip the sugar and the 2 whole eggs until the mixture sheets off the whisk. Then blend in the scalded milk and turn the mixture back into the saucepan. Have a sieve and a medium bowl handy for straining the custard once it has cooked. Using a wooden spatula, stir the custard continuously over medium-low heat 5 minutes, or until it reaches a temperature of 170°F and has thickened. Do not boil. Immediately pour it through a sieve into a bowl, removing the vanilla bean. (Rinse and dry the vanilla bean for use again.) Whisk in the remaining 2 egg yolks, and let the custard cool.

Assembling and Baking the Tart: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Fan out the apple slices on the pastry in a tight spiral pattern, forming a single layer. Pour the custard over the apples. Bake 40 minutes, or until a knife inserted midway between the center of the tart and the edge comes out clean. Cool the tart on a rack. Refrigerate if holding it more than 2 hours.

Serving: Serve the tart at room temperature, dusted lightly with confectioner’s sugar if desired.

Suggestions Wine: The tart’s assertive lemon flavor does not complement wine.

Menu: The tart is excellent after any menu where lemon and apples are not used. I like it particularly after Christmas Capon, Tagliatelle with Light Veal Ragù, Lamb with Black Olives, Porcini Veal Chops, January Pork, and Pan-Roasted Quail.

Torta della Nonna

A cross between filled shortbread and fruit tart, Nonna’s (Grandmother’s) dessert has a buttery crust and a homemade jam filling. It is a homey dessert, a favorite finish to Sunday dinners in Emilia-Romagna.

Jam tarts are found throughout Italy, but this particular one reminds me of Parma and Bologna. I first tasted the sweet/tart filling at the Atti bake shop, Bologna’s favorite source for home-style sweets. There it is described as brusca, meaning tart and fresh. The crust was inspired by a dessert made by Parma hostess Elsa Zannoni.

I have taken some liberties with the recipe. By creaming the butter and sugar, and eliminating some flour in the bottom crust, the tart is shorter, crisper, and even more like shortbread. Flour added to the top crust makes it less fragile, so it can be woven into the traditional lattice. Absolutely essential to the tart’s success is having the butter between 62° and 72°F so it can fluff to maximum volume and easily absorb all the flour.

[Makes 1 tart, serving 8 to 10]

Homemade Tart Jam (makes 2 cups)

1½ cups (12 ounces) dried apricots, peaches, or pitted prunes

6 tablespoons dry white wine

3 tablespoons sugar

Pastry

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

10 tablespoons (5 ounces) unsalted butter, at room temperature

¾ cup (5.25 ounces) sugar

2 teaspoons grated lemon zest

1 cup (4 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

1 cup (4 ounces) cake flour

Glaze

1 large egg, beaten

Method Working Ahead: The jam holds in the refrigerator 2 weeks and freezes 3 months. The dough can be made 24 hours ahead; wrap and chill it in the refrigerator. The finished tart keeps well, wrapped and chilled, 1 week.

Making the Jam: In a saucepan, combine the dried fruit, wine, sugar, and enough water to cover the fruit. Let it stand 20 minutes to 1 hour. Then bring the liquid to a gentle bubble. Turn the heat to low, cover the pot securely, and cook 30 minutes, or until the fruit is very soft. Taste for sweetness, adding more sugar if desired. Set it aside to cool.

Making the Pastry: Use the 1 tablespoon butter to grease a 9-inch tart pan with a removable bottom. In a medium bowl, cream the butter, sugar, and lemon zest with an electric beater at medium speed. Take 8 to 10 minutes, fluffing the butter to three times its original volume.

Thoroughly mix the flours in another bowl. Measure out 1½ cups by spooning the flour into measuring cups and leveling it with a flat knife blade. Using a spatula, fold the 1½ cups into the creamed butter, and blend well. Take two thirds of the dough, roll it out quite thick (¼ to ½ inch), and then pat the dough into the tart pan, pressing it into the pan’s sides. Work the remaining flour into the remaining dough. Pat it into a flattened ball. Refrigerate both portions of pastry at least 45 minutes.

Baking the Crust: Preheat the oven to 375°F, and place a rack in the center of the oven. Prick the crust in the tart pan with a fork. Set on a baking sheet, bake 20 minutes, or until pale gold. Remove it from the oven and cool on a rack.

Finishing the Tart: Meanwhile, roll out the remaining dough on a floured surface to form a 10-inch circle. Cut it into long strips about ¾ inch wide. Spread the fruit filling evenly over the cooled crust. Preheat the oven to 350°F.

Create a lattice top by laying five strips across the tart, parallel to each other and spaced about ½ inch apart. Use some of the beaten egg to seal them to the rim of the baked crust. Make a diagonal lattice with five more strips, spaced ½ inch apart. Press them into the rim of the baked crust. Brush all the pastry with beaten egg.

Baking and Serving: Bake the tart on the baking sheet 45 minutes to 1 hour, or until the top is golden brown. Cool it on a rack, and cut in narrow wedges.

Suggestions Wine: On special occasions in Parma, the torta is served with the local sweet Malvasia wine. A Moscato from Sardegna or the Piedmont makes a fine stand-in. Usually the tart is eaten on its own after dinner, or in the afternoon with coffee.

Menu: Serve the tart after an elegant meal or an informal one, after Rabbit Dukes of Modena, Oven-Glazed Porcini, Seafood Stew Romagna, Riccardo Rimondi’s Chicken Cacciatora, Beef-Wrapped Sausage, or Lamb, Garlic, and Potato Roast.

Torta La Greppia

Swirls of golden zabaione cream on top, tangy jam and crisp cookie crust underneath—from Parma’s Ristorante La Greppia.

[Makes 1 tart, serving 6 to 8]

Jam Filling

1½ cups Homemade Tart Jam, made with pitted prunes and ½ teaspoon grated lemon zest

Pastry

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons (2½ ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons (2½ ounces) cake flour

6 tablespoons (22/3 ounces) sugar

¼ teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon grated lemon zest

Pinch of salt

6 tablespoons (3 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into chunks

1 large egg, beaten with 1 tablespoon cold water

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

Zabaione Cream

6 large egg yolks

½ cup plus 3 tablespoons dry Marsala

¼ cup sugar

¾ cup heavy cream, chilled, whipped until stiff

Method Working Ahead: The jam keeps, covered, in the refrigerator 2 weeks and freezes 3 months. The pastry can be baked 24 hours before assembling the tart, and the zabaione can be cooked, chilled, and refrigerated 1 day ahead. The finished tart is best served within 8 hours after it is assembled. Store it in the refrigerator.

Making the Pastry in a Food Processor: Combine the flours, sugar, baking powder, lemon zest, and salt in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. Cut in the butter until reduced to a fine crumb. Add the egg and water, and process with the on/off pulse until the mixture begins to gather together in clumps. Turn the pastry out onto a piece of plastic wrap or wax paper. Gather it into a ball, wrap, and chill at least 30 minutes.

Making the Pastry by Hand: Combine the dry ingredients in a large shallow bowl. With a pastry cutter or your fingertips, work in the cold butter until only a few long shales of butter are visible. Sprinkle the pastry with the egg and water. Toss with a fork. Mix only long enough to barely moisten the flour. Gather the pastry into a ball, wrap, and refrigerate at least 30 minutes.

Baking the Pastry: Use the ½ tablespoon butter to grease a 9-inch tart pan with removable bottom. Generously flour a work surface, and roll out the pastry to less than 1/8 inch thick. (If the weather is humid, roll the pastry between pieces of wax paper.) Fit the pastry into the tart pan, prick it with a fork, and chill at least 30 minutes. Preheat the oven to 375°F. Line the crust with aluminum foil, and weight it with dried beans or rice. Bake 10 minutes. Remove the weights and foil, and continue baking another 5 to 8 minutes, or until golden brown. Cool on a rack.

Making the Zabaione: Bring a saucepan half full of water to a boil. In a large metal bowl, whisk together the egg yolks, Marsala, and sugar. Set the bowl over the boiling water and whisk 5 minutes, or until the mixture is thick and reads 165°F on an instant-reading thermometer. Turn the zabaione into a storage container, and cool it to room temperature. Cover and chill in the refrigerator several hours or overnight. (The zabaione must be cold when the cream is folded into it.) Fold in the stiffly beaten cream shortly before assembling the tart.

Assembling and Serving the Tart: Evenly spread the jam over the crust. With a long spatula, swirl on the zabaione cream, covering the jam completely. Chill the tart until about 20 minutes before serving. Cut it into wedges.

Suggestions Wine: Small glasses of lightly chilled sweet (semi-secco or dolce) Marsala Superiore Riserva are excellent with this. This is a fine sipping Marsala that can rival a port or Madeira.

Menu: Serve after Porcini Veal Chops, Pan-Roasted Quail, Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken, or main-dish portions of Tagliatelle with Prosciutto di Parma or Tortelli of Ricotta and Fresh Greens, followed by a green salad.

Torta di Farro Messisbugo

This tart is edible time travel from the 16th century, when Ferrara bakers created the sweet in the palace kitchens of Cardinal Ippolito d’Este. Inside a sweet saffron crust plumped barley, cream cheese, orange zest, and spices bake into a subtle pudding. During the Cardinal’s time, sweets like this often appeared at the beginning of a meal with prosciutto, salads, and marzipan biscuits. Even though it is a dessert today, the tart’s grain and cheese make it nourishing enough to follow a simple main-dish salad.

[Makes 1 tart, serving 6 to 8]

Pastry

2/3 cup (2 2/3 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

½ cup (2 ounces) cake flour

2 tablespoons sugar

3 tablespoons unsalted butter, chilled

1/8 teaspoon saffron threads, soaked in 1 tablespoon cold water

1 large egg yolk

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

Filling

1/3 cup (2 ounces) whole-grain spelt or pearl barley

Generous pinch of salt

3 cups water

8 ounces fresh Italian cheese (Casatella, Raviggiolo, or Robbiola) or American cream cheese (preferably without guar gum)

2/3 cup plus 1 tablespoon (5 ounces) sugar

2 large eggs, beaten

4 tablespoons (2 ounces) unsalted butter, melted

Pinch of salt

1/8 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon grated orange zest

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 cup (5 ounces) raisins or coarsely chopped dried apricots, soaked in hot water to cover

Topping

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

1¼ teaspoons sugar

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

Generous pinch of freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons candied melon seed, candied anise seed, or toasted pine nuts

Method Working Ahead: The crust and grain can be cooked 1 day in advance. Cover both and store in the refrigerator. The finished tart is best eaten at room temperature within 8 hours after baking, but it holds well in the refrigerator 1 or 2 days.

Making the Pastry by Hand: Combine the dry ingredients in a shallow bowl. Rub the butter in with your fingertips until there are only a few crumbly shales visible. Make a well in the center of the mixture, and pour in the saffron water and the egg yolk. Use a fork to blend the liquids, and then gradually scrape in flour from the well’s walls. A pastry cutter helps blend in the last of the dry ingredients. Work the dough only long enough for it to gather into a ball. Wrap, and chill 30 minutes.

Making the Pastry in a Food Processor: Combine the dry ingredients in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. Blend in the butter. Then add the egg yolk and saffron water. Use the on/off pulse to blend the dough only long enough for clumps to form. Turn the pastry out onto a sheet of plastic wrap or wax paper. Gather it into a ball, wrap, and chill 30 minutes.

Baking the Crust: Generously flour a work surface. Butter a 9-inch tart pan with removable bottom and fluted sides with the ½ tablespoon butter. Roll out the pastry very thin, and fit it into the pan. If the weather is humid, roll it out between sheets of wax paper. Trim the excess dough leaving a 1½-inch overhang. Fold that over to the inside of the pan so the crust stands at least ¼ inch above its rim. Chill 30 minutes to overnight. Preheat the oven to 400°F. Prick the pastry with a fork. Line it with aluminum foil and weight with dried beans or rice. Bake 10 minutes. Remove the liner and weights, and bake another 5 minutes, or until pale gold. Cool on a rack.

Making the Filling: If you are using spelt, soak it overnight in cold water, then drain and turn it into a 2-quart saucepan. Cover with 2 inches of cold water. Cover the pan, and bubble gently 2 hours, or until the grain is tender. Drain well and cool. Barley needs no soaking. Simply cover it with the 3 cups water and cook, covered, at a gentle bubble 1¼ hours, or until very tender. Drain well and cool. Preheat the oven to 350°F, and set a rack in the lower third of the oven. Have a baking sheet handy. Beat the cheese and sugar until creamy. Beat in the eggs until smooth. Then blend in the 4 tablespoons melted butter and the salt, black pepper, orange zest, and cinnamon. (Eliminate the salt if the cheese is at all salty.) Stir in the drained raisins or apricots and the cooked and well-drained grain.

Baking and Serving: Set the pastry shell on the baking sheet. Pour in the filling. Spread the 2 tablespoons melted butter over the top. Slip the baking sheet into the oven, and bake 20 minutes. Sprinkle the sugar, cinnamon, pepper, and seeds or nuts over the top. Bake another 35 minutes, or until a knife inserted in the center comes out clean. Cool on a rack and serve at room temperature, sliced into small wedges.

Suggestions Wine: From Ferrara’s Bosco Eliceo wine area, drink a sweet red Fortana Amabile or from Romagna have a sweet red Cagnina or the sweet white Moscato wines of Sardinia.

Menu: For the simplest dining, have the Salad of Tart Greens with Prosciutto and Warm Balsamic Dressing as the main dish and serve the tart for dessert. The tart is excellent after any light menu not flavored with cinnamon. Ferrara’s Rabbit Roasted with Sweet Fennel, Fresh Tuna Adriatic Style, and Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, are particularly good choices. For menus suggestive of the tart’s origins, have Rabbit Dukes of Modena, Artusi’s Delight, or Christmas Capon.

Cook’s Notes Fresh Italian Cheeses: A creamy full-fat cheese, sweet with freshness, is needed in this tart. The ones listed come from Emilia-Romagna and are in their prime during their first 10 days of life. Taste available imports (whether from the region or not) for sharpness, bitter undertones, or excess salt. Better to use a fine domestic cream cheese than an import past its prime.

Old engraving of Ferrara

Farro and Spelt

Although nothing can be exactly as it was, dishes like this give us a glimpse into the past. Pastry crusts with saffron were common in the 16th century, and cinnamon, pepper, and orange flavored sweet as well as savory dishes. Typical of the period, too, was the pound each of butter and sugar that I have eliminated in this modern version. The original recipe calls for either wheat kernels, farro, or rice—a choice that appears in many recipes of the era. Farro is spelt, or emmer, two very old strains of wheat used by the ancient Romans and still found in central Italian dishes today. Although there are slight differences between the two grains, in Italy farro refers to them both. After discovering that wheat grains bake into hard kernels, I turned to spelt. Surprisingly, it closely resembles barley in flavor. To find spelt in the United States. But the even more readily available barley makes a fine alternative. The homey-sounding tart turns exotic with its topping of either candied melon seeds or anise seeds, which suggest the Arab influences on the sweets of the Renaissance. Toasted pine nuts are the third choice offered in the original recipe.

Mandorlini del Ponte

These are meringues with a difference. The egg whites are cooked before baking, making the meringue crackly instead of chewy. Chunks of toasted almond add even more crunch. This is an heirloom recipe from the village of Pontelagoscuro (Bridge of the Dark Lake) in Ferrara province. Serve the meringues whenever a light sweet is needed to round out a menu.

[Makes 30 cookies]

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

3 tablespoons all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

4 large egg whites

1 cup plus 2 tablespoons (8 ounces) sugar

2/3 cup (22/3 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

2 cups (8 ounces) blanched almonds, toasted and coarsely chopped

Method Working Ahead: The meringues are at their best eaten within a day or two of baking, but they are still very good up to 1 week later. Store them at room temperature in an airtight container.

Making the Meringues: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Use the ½ tablespoon butter to grease a cookie sheet. Sprinkle it with 3 tablespoons flour and discard the excess. Bring a saucepan half filled with water to a boil over medium heat. Using a hand-held electric mixer, whip the egg whites to soft peaks in a metal bowl. Slowly beat in the sugar. Put the bowl over the bubbling water, taking care that it does not touch the water. Beat 5 minutes at high speed, or until the whites become thick and shiny, coating the bottom of the bowl. Beat in the flour until just blended. Remove the bowl from the heat, and fold in the almonds. Drop the batter by tablespoonfuls onto the baking sheet. Bake 30 minutes, or until pale gold. Remove them immediately to a rack, and allow to cool.

Suggestions Menu: Serve the cookies with fruit or after-dinner coffee, or as dessert after a robust menu.

Gialetti di Romagna

Cornmeal and polenta have been part of Emilia-Romagna’s repertoire since corn first came from the Americas via Spain. These crunchy cookies are found throughout the southern part of Emilia-Romagna, as well as in the neighboring Veneto region. Homey looking and fragrant with cornmeal, they are superb with fresh fruit or just by themselves with espresso.

[Makes about 50 cookies]

1 cup (4 ounces) cornstarch

1 cup (5 ounces) coarse yellow cornmeal

2 cups (8 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

Generous pinch of salt

1 cup (8 ounces) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 cup (7 ounces) sugar

3 large eggs

1 tablespoon water

1½ teaspoons grated lemon zest

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Generous ½ cup (2½ ounces) raisins, soaked in hot water for 15 minutes and drained

½ cup (2 ounces) pine nuts, toasted

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

Method Working Ahead: The cookie dough can be mixed and refrigerated, tightly wrapped, overnight. The baked biscuits store well in a sealed tin about 1 week and freeze 3 months.

Making the Dough: Blend the cornstarch, cornmeal, flour, and salt in a bowl until well mixed. Combine the butter and sugar in the bowl of an electric mixer. Beat at medium speed with the paddle attachment 8 minutes, or until pale and very fluffy. A hand-held electric mixer can also be used. Beat in the eggs, one at a time, making sure the mixture is fluffy before adding the next egg. Then beat in the water, lemon zest, and vanilla. Keeping the speed at medium, beat in about 1½ cups of the dry ingredients until just blended. Then blend in another cup until barely mixed. Add the rest of the dry ingredients, along with the raisins and nuts. The dough will be thick, sticky, and soft. Cover the bowl and refrigerate 30 minutes.

Shaping and Baking: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Use the ½ tablespoon butter to lightly grease a 14 by 18-inch cookie sheet. The cookies will bake in three batches. Drop the chilled cookie dough by teaspoonfuls onto the baking sheet, spacing them 1 to 1½ inches apart. Make a crosshatch pattern on top of each biscuit by dipping a dinner fork in a glass of water, then pressing the back of the fork gently into the cookie dough, flattening it slightly. Wet the fork again, and press it into the dough at right angles to the first impression. Chill the unused dough. Bake the biscuits 20 minutes, or until they are pale blond with golden brown edges. Remove the cookie sheet from the oven, and use a metal spatula to remove the biscuits to a rack to cool. Drop another batch of the chilled dough by teaspoonfuls onto the baking sheet, and press and bake as before. Repeat with the third batch. Make sure the dough is cold when the cookies go into the oven.

Serving: Pile the Gialetti on a colorful plate, and serve.

Suggestions Wine: In Bologna, a local Lambrusco is a fine dipping medium for Gialetti. In the United States, serve them with lightly chilled dry Marsala or with espresso.

Menu: The Gialetti, served with or without fruit, are a fine finish to a rich meal. Also serve them after Romagna seafood dishes like Fresh Tuna Adriatic Style, Herbed Seafood Grill, or “Priest Stranglers” with Fresh Clams and Squid; and after main dishes like Grilled Beef with Balsamic Glaze, Lamb with Black Olives, or Lamb, Garlic, and Potato Roast. They pair beautifully with Baked Pears with Fresh Grape Syrup.

Cook’s Notes Using Cornstarch: I have found that adding cornstarch to the traditional blend of cornmeal and flour gives the cookies a pleasing tenderness.

Ravioli Dolci di Paola Bini

Tender pastry turnovers filled with winter fruits, sweet squash, and chestnuts are a specialty of Villa Gaidello, near Modena. They originated in Medieval convent kitchens. There, fresh grape syrup and fruits were cooked into a conserve called savor. Often chestnuts were blended in, just as Villa Gaidello does today. And now, as then, the ravioli are excellent with sweet wine.

Throughout Emilia-Romagna variations on this theme crop up at Christmas, just before Lent, and on local saints’ days. Each area gives the pastries its own name; tortelli, tortellini, cappelletti, or ravioli, even though their shapes seldom change. Some cooks bake the turnovers, as in this recipe, while others fry them.

Whatever the name, their sugarless fillings always recall the days when sugar was dearly priced. Then, spiced fruits and cooked-down grape syrup satisfied most sweet tooths. Today, present the ravioli at the end of special dinners, especially at Christmas time.

Pastry

1 cup (4 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

1 cup (4 ounces) cake flour

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons (4 ounces) sugar

¼ teaspoon baking powder

2 teaspoons grated lemon zest

6 tablespoons (3 ounces) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into chunks

1 large egg beaten with 2 tablespoons cold water

Filling

2 cups Fresh Grape Syrup, or 1¼ pounds seedless red grapes, stemmed

½ large quince or Granny Smith apple, cored and chopped

½ medium Bosc pear, cored and chopped

½ medium Winesap or Rome Beauty apple, cored and chopped

½ cup diced peeled butternut squash

½ cup water

2 teaspoons grated orange zest

1 teaspoon grated lemon zest

½ cup peeled roasted or canned chestnuts, crumbled

1/3 cup golden raisins

¼ cup pine nuts, toasted

1 tablespoon Strega liqueur

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

Glaze

1 large egg, beaten

Method Working Ahead: The pastry and filling can be made up to 3 days before assembling the ravioli. Once baked, the ravioli freeze well 1 month and hold in the refrigerator, well wrapped, 4 days. Reheat 5 minutes at 350°F before serving.

Making the Pastry by Hand: Combine the dry ingredients, including the lemon zest, in a bowl. Cut in the butter with a pastry cutter until the mixture resembles coarse meal. Using a fork, toss in the egg/water mixture until the dough can be gathered into a ball. If it is too dry, sprinkle with another tablespoon of water, toss, and then gather into a ball. Wrap, and chill at least 2 hours.

Making the Pastry in a Food Processor: Combine the dry ingredients, including the lemon zest, in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. Process 10 seconds. Add the butter and process until the mixture looks like coarse meal. Sprinkle with the egg mixture, and use the on/off pulse until the dough gathers in clumps. Turn it out onto a board, gather into a ball, and wrap in plastic wrap. Chill at least 2 hours.

Making the Filling: In a saucepan combine the grape syrup or fresh grapes, quince, pear, apple, squash, water, and citrus zests. Bring to a lively bubble and partially cover. Reduce the heat so the fruit is bubbling slowly, and cook 2 hours, stirring frequently, until the pieces are breaking down and very soft. Check for sticking, adding a little water if necessary. Pass the fruit through a food mill fitted with the coarse blade. Turn it back into the saucepan and cook over medium heat, uncovered, 45 minutes. Stir frequently and check for scorching. The fruit should thicken and reduce but not burn. It is ready when it thickly coats a wooden spoon. Cool, and set aside ½ cup for another use. Stir in the chestnuts, raisins, pine nuts, and Strega.

Assembling and Baking: Preheat the oven to 350°F. Use the tablespoon of butter to grease two cookie sheets. Roll out the dough on a floured board to less than 1/8 inch thick. Use a scalloped biscuit cutter to cut out 3-inch rounds. Place a teaspoon of filling in the center of each round and fold it in half, sealing the edges with a little of the beaten egg. Reroll and fill the scraps of dough. Arrange the ravioli on baking sheets, and brush them with the egg glaze. Bake the ravioli, a sheet at a time, 20 minutes or until golden brown. Cool on a rack.

Serving: Serve the ravioli piled on a colorful platter. At Christmas we arrange them on a bed of fresh pine. Some cooks moisten the ravioli with Fresh Grape Syrup.

Suggestions Wine: A sweet white Albana Amabile or Passito from Romagna is heavenly with the ravioli. Try also Malvasia delle Lipari from Sicily, or Torcolato of the Veneto.

Menu: The ravioli pair well with old-style dishes like Christmas Capon, Artusi’s Delight, Giovanna’s Wine-Basted Rabbit, and Rabbit Dukes of Modena, or after a main course of tagliatelle with Piacenza’s Porcini Tomato Sauce.

Torte Maria Luigia

Few ever guess the secret ingredient of these pastries from Parma. Enveloped in the sweet crust are tastes of vanilla, citron, and almond. The mystery lies in their filling. Cooking fresh spinach in sugar may come as a surprise to many, but sweet spinach tarts are found in Reggio, in France, and even in 18th-century England. I suspect if we could stroll through the markets of ancient Persia and India, we would find them there too. Ugo Falavigna, of Parma’s Pasticerria Torino, believes the original of this recipe came from Austria to Parma in the early 19th century. He claims it came from the court cook to Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma. Whatever their origins, the turnovers are absolutely delicious and elegant enough to end the most important of dinners. I often serve them after a frozen or fruit-based dessert with coffee in the living room.

[Makes 50 pastries]

Pastry

2½ cups (10 ounces) cake flour

2¼ cups (9 ounces) all-purpose unbleached flour (organic stone-ground preferred)

1 cup (7 ounces) sugar

Pinch of salt

1 cup plus 4 tablespoons (10 ounces) unsalted butter, cut into chunks

2 to 5 tablespoons dry white wine

1 large egg, beaten

Filling

12 ounces fresh spinach, trimmed

11/3 cups (9½ ounces) sugar

1 teaspoon dark rum

1½ cups (6 ounces) blanched almonds, toasted and finely chopped

Generous ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1/8 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1/3 cup (1½ ounces) candied citron, finely minced

1½ teaspoons vanilla extract

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

Glaze

1 large egg, beaten

¼ cup sugar

Method Working Ahead: The filling and pastry can be made 1 day ahead. Cover both and refrigerate. The pastries are best eaten within a few days of baking. Store them in a sealed tin. They also freeze well. Rid them of any sogginess after defrosting by crisping them in a 400°F oven about 10 minutes before serving.

Making the Pastry in a Food Processor: In smaller food processors, this recipe is best done in two batches. Combine the flours, sugar, and salt in a food processor fitted with the steel blade. Process a few seconds. Add the butter, processing until the mixture looks like coarse meal. Blend together 2 tablespoons of the wine and the egg. Add this to the pastry, processing with the on/off pulse only until the dough begins to gather into small crumbs. If it is too dry to be gathered into a small ball, sprinkle with another tablespoon or two of wine and process a few seconds. Wrap, and chill 30 minutes or as long as 24 hours.

Making the Pastry by Hand: Combine the flours, sugar, and salt in a large shallow bowl. With your fingertips or a pastry cutter, work in the butter until there are just a few large shales visible. Beat together 2 tablespoons of the wine and the egg. Using a fork, toss the pastry with the egg mixture. Do not overmix. Just blend until the pastry barely holds together when gathered into a ball. If it is too dry, sprinkle with another 1 or 2 tablespoons of wine and toss. Wrap, and chill 30 minutes or as long as 24 hours.

Cooking the Spinach: Fill a sink with cold water, and rinse the spinach well. Measure the sugar into a 4- to 6-quart pot. Lift the spinach out of the water and transfer it right to the pot. Set the pot, uncovered, over high heat and cook, stirring occasionally, 5 to 8 minutes. The spinach should be wilted but still bright green. Set a colander in a bowl and drain the spinach, reserving its cooking liquid. Set the spinach aside to cool. Once it is cool, squeeze out the excess moisture and finely chop.

Making the Filling: Turn the spinach cooking liquid back into the spinach cooking pot and set it over high heat. Boil, uncovered, 8 to 10 minutes, or until the bubbles are big and shiny. This means all the water has evaporated and now the sugar is totally liquified and boiling on its own. This liquid will be pale celery green and will thicken. Turn off the heat. Put the chopped spinach in the bowl that held the cooking liquid. Pour in the hot syrup from the pot, taking care that it does not spatter. Let the mixture cool. Then stir in the rum, almonds, spices, citron, and vanilla.

Shaping and Baking: Have a small bowl of water handy. Use the ½ tablespoon butter to grease a large baking sheet. Preheat the oven to 375°F. Generously flour a work surface, and roll out half the dough to a little less than 1/8 inch thick. (In humid weather roll the dough out between sheets of wax paper.) Cut it into rounds with a 3½-inch fluted biscuit cutter or a glass. If time allows, chill the rounds 30 minutes before filling them. Dip your finger in the water and moisten the edges of the rounds. Place a generous teaspoonful of filling in the center of each round. Fold the dough over so it forms a half moon, and seal the edges. Set the crescents on the baking sheet. Brush the pastries with beaten egg and sprinkle lightly with sugar. Bake in the center of the oven 25 minutes, or until the edges are golden brown. Cool the pastries on a rack, and repeat with the remaining dough.

Suggestions Wine: Serve the pastries with a sweet Malvasia or a Moscato d’Asti.

Menu: In keeping with their heritage, offer the pastries after a period meal of Almond Spice Broth, Christmas Capon, and chunks of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese with fresh fennel. They are also excellent after His Eminence’s Baked Penne or Lasagne Dukes of Ferrara.

Espresso and Mascarpone Semi-Freddo

Semi-Freddo di Espresso e Mascarpone

Semi-freddo (partially frozen) always suggests to me a cross between soft ice cream and the richest of frozen mousses. In this one, Italian meringue helps aerate the espresso cream. But mascarpone intensifies the taste and gives the espresso depth.

This style of dessert is a contemporary addition to Emilia-Romagna’s home repertoire. There, egg whites are beaten with a little sugar and folded into the mousse. But now that raw eggs are a concern in the United States, I have cooked the whites with a hot sugar syrup, creating Italian meringue. The result is even more elegant than the original. Serve partially frozen in wine glasses, or unfrozen over wedges of rum-soaked Spanish Sponge Cake.

This recipe is particularly generous. Making a smaller amount can be tricky, as electric mixers often have difficulty beating only a few egg whites. If you need only half this amount, make the entire recipe and divide it in half, freezing the other half for another time.

[Serves 10 to 12]

Espresso Custard

6 tablespoons very strong brewed espresso, or 3 tablespoons instant espresso granules and boiling water

4 large egg yolks

4 tablespoons (11/3 ounces) sugar

2 tablespoons dark rum

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

1 pound mascarpone cheese

¼ cup heavy cream

Italian Meringue

4 large egg whites, at room temperature

¾ cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

¼ cup water

Garnish

2 ounces bittersweet chocolate, shaved

Method Working Ahead: The semi-freddo freezes well 1 month. Serve it partially defrosted. It is also excellent served merely chilled within an hour or so of making. After that, the meringue begins to break down and the mousse becomes too soft.

Making the Custard: If you are using coffee granules, pour them into a glass measuring cup. Add enough boiling water to make 1/3 cup. Stir and let cool. In a large metal bowl, whisk together the egg yolks, sugar, coffee, rum, and vanilla. Set the bowl over a pan of boiling water, taking care that the bowl does not touch the water. Whisk 3 minutes, or until thick. The custard should reach 160°F on an instant-reading thermometer. Scrape it into a small bowl, cool, cover, and chill in the refrigerator. Soften the mascarpone with the cream. Fold it into the chilled custard, blending completely but keeping the mixture light.

Making the Italian Meringue: In an Italian meringue hot sugar syrup is poured into egg whites as they are beaten, cooking and stabilizing them so they will not break down when folded into desserts. The key to success is in not overbeating the whites before the sugar reaches its proper temperature of 248° to 250°F. Starting to beat the whites as the sugar syrup comes close to its final temperature guards against overbeating.

Have a candy thermometer handy. Put the whites in the bowl of an electric mixer. Pour the ¾ cup sugar and ¼ cup water into a tiny saucepan, and set over medium heat. Cook at a lively bubble 3 minutes, or until the syrup is clear. Wash down the sides of the pan frequently with a brush dipped in water. Once the syrup is clear, turn the heat to high and put the thermometer in the pan. When the syrup reaches 245°F, turn on the mixer at medium speed. Wait a few seconds and then turn the machine to high speed. By the time the syrup is at 248° to 250°F, the whites should be beaten to stiff but moist peaks and should look smooth (if they are gathering together into clumps, they are overbeaten). Continue beating the whites as you immediately pour the hot syrup into the bowl. Keep beating on high speed about 3 minutes. Then turn the mixer down to medium, and beat until the whites cool to room temperature.

Finishing and Serving: Fold the whites into the custard, keeping it light. Spoon the mixture into a container and freeze. Three hours before serving, transfer it to the refrigerator. Serve the semi-freddo in wine glasses, or scoop ovals of the mousse onto dessert dishes. Sprinkle with the chocolate shavings. To serve without freezing, spoon the mixture into an attractive serving-dish or wine glasses, and refrigerate. Serve within an hour, garnished with the chocolate shavings.

Suggestions Wine: A dry Marsala with the semi-freddo.

Menu: Serve after Pan-Roasted Quail, Lemon Roast Veal with Rosemary, Erminia’s Pan-Crisped Chicken, or other dishes made with lemon or balsamic vinegar.

Cook’s Notes Mascarpone: Mascarpone comes in two consistencies: a thick cream and a solid cheese. For this recipe, seek out the thick cream.

Zuppa Inglese di Vincenzo Agnoletti

Here frozen layers of almond mousse and chocolate cream are sealed between slivers of light sponge cake. This sumptuous dessert is easily prepared ahead (and can be doubled) and is impressive enough for the most important of dinners. Covered in swirls of whipped cream, the cake’s finishing touch is a gilding of green and red from crushed pistachios and slivers of candied cherry. Parma’s Duchess Marie Louise dined on a dessert very similar to this one in the early part of the last century. Today there is a sense of timelessness to the dish. Serve it when a menu needs a classical, polished finish.

[Serves 8]

Filling

¼ cup water

6 tablespoons (22/3 ounces) sugar

8 large egg yolks

6 tablespoons almond syrup (see Note)

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2½ ounces bittersweet chocolate, melted

1/3 cup shelled green pistachio nuts, crushed

1 cup heavy cream, whipped and chilled

Cake

1/3 cup dark rum

3 tablespoons sugar

One 9-inch square Spanish Sponge Cake

Frosting

1½ cups chilled heavy cream, whipped until stiff

2 candied red cherries, each cut into 8 slivers

¼ cup shelled green pistachio nuts

Method Working Ahead: The sugar syrup holds, covered, in the refrigerator at least 1 month. The fillings can be made 1 day ahead; store them, covered, in the refrigerator. Freeze the finished dessert up to 1 month. Unmold it, frost, and serve.

Making the Filling: Combine the water and the 6 tablespoons sugar in a tiny saucepan. Bring to a gentle bubble over medium heat. Once the liquid is clear and the sugar is melted (about 3 minutes), cook over medium heat another 2 minutes. Allow to cool. Strain the cooled syrup into a large stainless steel bowl. Whisk in the egg yolks and 3 tablespoons of the almond syrup. Set the bowl over a pot of boiling water, making sure it does not touch the water. Whisk until the custard is very thick, 2 to 5 minutes. It will reach about 165°F on an instant-reading thermometer. Whisk in the last 3 tablespoons almond syrup and the vanilla. Immediately turn the custard into the bowl of an electric mixer, and beat at medium-low speed 5 minutes. Then beat at low speed 10 minutes, or until cooled to room temperature. Scoop half the mixture into another bowl. Thoroughly blend the melted chocolate into that custard. Stir the crushed pistachios into the remaining custard. Fold half the whipped cream into the chocolate mixture. Fold the remaining cream into the almond custard. Chill the custards 3 hours or as long as 24.