2 The Iroquois Family of Nations

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people envisioned themselves as being one giant family. In fact, they formed a family of nations. The name, Haudenosaunee, which is used to refer to this Iroquoian nation, means, “People of the Longhouse.” The symbolic longhouse they shared was the northeast woodlands. The Mohawk were the Guardians of the Eastern Door of the Haudenosaunee’s great figurative longhouse. The Seneca were the Guardians of the Western Door. Lineage was traced through the maternal, or mother’s side, of the longhouse family.

In descriptions of their large, extended family, the Haudenosaunee referred to the tribes within their nation as brothers. The Elder Brothers of the Haudenosaunee are the Onundagaono (Onondaga), Kanienkahagen (Mohawk), and Onondowahgah (Seneca). The Younger Brothers are the Onayotekaono (Oneida), Guyohkohnyoh (Cayuga), and Ska-Ruh-Reh (Tuscarora).

The Haudenosaunee taught their children to respect and honor both their younger and elder brother tribes. They also taught their children to be thankful for their “Three Sisters”—corn, squash, and beans. These three important food staples supported, sustained, and nurtured the growth of the Haudenosaunee nation.

Iroquois children inherited the clan symbol and ties of their mother. When a man and a woman married, the man moved from his mother’s longhouse to the longhouse of his wife. He owned only personal items, clothing, and weapons.

The true center of longhouse family relationships revolved around the fireside family. A fireside family, like a nuclear family, was made up of a mother, a father, and their children. The Iroquois family then branched out to include extended family or clan members. Tribal nationality was comprised of clans. Finally, the intertribal family of the nation was made up of the members of all of its smaller tribes, bands, or “brother” nations.

Another group of Native Americans that lived on the Atlantic Coast of North America was the Algonquians. The members of the Algonquian-language family formed alliances similar to the Iroquois Confederacy. However, these alliances were never as structured as that of the Haudenosaunees. They tended to be looser groupings of small bands of Algonquian peoples that joined together only during battle or to trade with one another.

Grand sachems, or chiefs, led Algonquian bands joined together as confederacies. The lesser chiefs of the individual tribal bands were known as sagamores. The grand sachems often served as negotiators for the sagamores. Algonquian tribes were often matrilineal; however, some, like the Mi’kmaq, were patrilineal.

Daily work was divided between the two moieties of a clan. When a member of one moiety died, the members of the other moiety would take care of the chores associated with the death of a family member. This allowed the deceased person’s immediate moiety members to attend solely to their mourning.

A group of Native American boys practice with bows and arrows. In Iroquois tribes, boys learned archery and other hunting skills at a young age. This training would serve them well when they became adults, and therefore responsible for providing food for their family.

Throughout the Northeast, women did the cooking, raised the children, and cared for the elderly members of their tribes. They did the weaving, tanning, pottery, and basket making. Women also made footwear and clothing for their families.

Women made cradleboards to make carrying their babies as they worked easier. The cradleboards were often decorated with ornate designs. Relatives and friends gave the woman special totems to hang from her child’s cradleboard. This was done in order to help keep the baby healthy and safe.

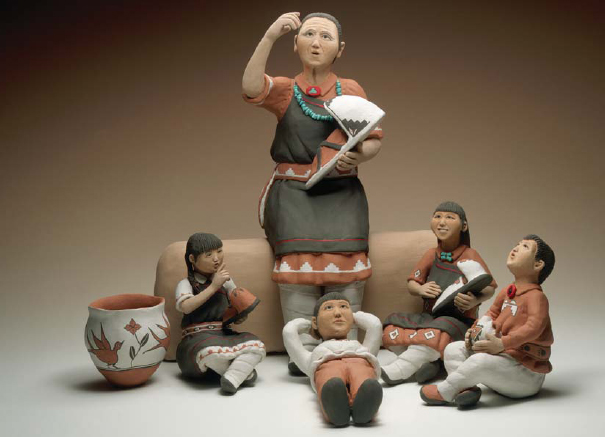

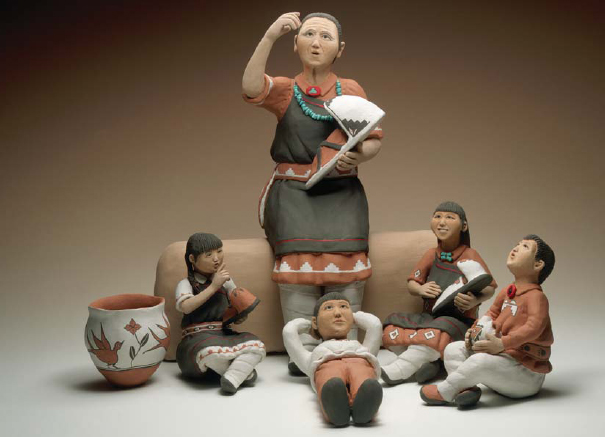

These small figures depict a Native American storyteller entertaining a group of young listeners. Storytelling was a popular pastime among the Native Americans of the northeast. Both the adult figure and the young girl to the right are holding infant children in cradleboards.

Northeastern mothers often bathed their children in cold lakes and streams. This was believed to be necessary to help ensure a young child’s survival through his or her first winter. The woodlands could be a cold and harsh place to live during the winter. Young children needed to be acclimated to the cold. Being bathed in cold water helped to acclimate the young.

The Mi’kmaq decorated their clothing with their clan symbol. They also painted it on their canoes, snowshoes, and other possessions.

The Haudenosaunee women owned all property, and a respected elder matron led each family clan. Female clan leaders chose the sachems, or clan chiefs, for their tribes. If the woman who chose a sachem became displeased with the way he was representing their people, she could have him removed from his leadership position.

Haudenosaunee women were the keepers of the “Three Sisters.” Mothers, daughters, and grandmothers sowed, tended, prayed over, and harvested the beans, squash, and corn that helped to feed their families. It was their responsibility to weed the fields and to store supplies of food for the family in underground caches.

The men of the Haudenosaunee nation hunted and trapped animals. They were brave warriors who protected their families and their nation. Haudenosaunee men were also responsible for making weapons and canoes. The clan sachems were men of the Haudenosaunee who represented their tribes at meetings of the Iroquois Confederacy. (If the men were from Algonquian tribes, then their sachems represented them at meetings of their own confederacies.)

The majority of the Haudenosaunee were divided into three main clans: the turtle, bear, and wolf clans. Animals played an important role in Haudenosaunee spiritual life. A clan’s totem animal was considered to be its kindred spirit. Animals were also often the main characters of religious and teaching stories told by the elders to the young.

Maternal uncles played an especially big role in the life of young male Haudenosaunees. Clans were linked through the mother’s bloodlines, so a young man learned his family history from his mother’s brothers. Maternal uncles were responsible for preparing their young nephews for clan life, important rituals, marriage, and the responsibilities of adult life.

Around the age of seven or eight, Haudenosaunee children were expected to begin performing chores. The chores that they were given helped ease the day-to-day workload of their fireside family. More importantly, the chores helped to prepare the children for their roles later on in life.

Young girls would help haul water and tend to the crops. They would also assist their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers with sewing and cooking. They learned to make clothing and footwear. They also learned to make cornhusk dolls and other toys for their younger siblings. Their aunts, grandmothers, and mothers shared stories and bits of wisdom with them as they worked. In this way, young girls gradually learned the skills necessary to be a responsible, productive wife and clan mother.

Haudenosaunee men were often away from home for long periods of time. Because of this, young boys were encouraged to “play” at fighting, hunting, and camping. This type of “play” helped them to learn important life skills.

Their mothers often made toy war clubs for them out of corn silk. The boys would use these soft clubs to participate in mock battles against their friends. This allowed them to learn important hand-to-hand combat skills.

To be capable providers and effective warriors, the young boys needed to perfect their use of snares, bow and arrows, blowguns, and other weapons. When their grandfathers, fathers, and uncles were home from hunting or war parties, the young boys learned how to make canoes, weapons, and tools. The elder men gave the younger men advice on how to become respected hunters, warriors, husbands, and fathers.

After a young boy killed his first deer, he was allowed to join the adult hunting parties. When he reached puberty, he was sent into the woods on a vision quest. A respected elder would often accompany the adolescent on this sacred journey.

At this time, the young man would demonstrate his physical strength, intelligence, and manliness. These were important assets, as life in the woodlands could be quite demanding. A young man would strive to demonstrate that he was capable of withstanding great challenges in order to protect and provide for his family and nation.

Around the year 1570, two influential men, Hiawatha and Deganawida, first encouraged the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca to unite. The Huron prophet Deganawida spoke of a vision of the tribes united beneath a “Great Tree of Peace.” Hiawatha, a Mohawk medicine man, traveled by canoe throughout the Haudenosaunee territories speaking about the importance of unity.

Hiawatha and Deganawida’s efforts were rewarded with the formation of the Iroquois Confederacy. This confederacy of tribes, or Iroquois nations, started out as a union of five nations. In the early 1700s, the Tuscarora joined the Haudenosaunee family of nations, bringing the number to six. Many historians now believe that the United States of America owes a debt of gratitude, not only to the Roman ideals of democracy and the republic, but also to the political models of the Haudenosaunee’s Pine Tree Sachems, Grand Council, and Grand Council Fire.

The young man might also reveal his dreams to his elder companion. The elder would consider the young man’s dreams carefully and identify the guardian spirit that was trying to show itself to the young man. The young man would then find or carve a symbol of that spirit to keep as a personal totem.

A young girl generally came of age around the same time that she became capable of bearing children. At this time, the girl’s mother would build a small wigwam outside the main village. The girl would retreat into the wigwam for several days. She would pray for the blessings of healthy children, a good husband, and a long life. She would fast during this time, drinking only water.

Delaware boys participated in a coming-of-age initiation rite called the Youth’s Vigil. A boy would enter the woods and fast for a number of days. Hopefully, he would have a vision during this time that revealed the spirit guides and forces that would protect and direct him from young manhood to old age.

For the Delaware tribe of the Algonquian people, marriage and divorce were simple matters. A man and woman who moved in together were considered to be husband and wife. If either one wanted a divorce, the man would leave the family dwelling. It was the wife’s right to retain custody of the home and children.

Family life in the woodlands culture area was not all work. Although the children owned few possessions, their parents did make toys for them. Young girls and boys used sticks to roll hoops made out of birch bark along the ground. Animal skin balls were stuffed with feathers or fur. Men and boys played a demanding game, much like modern-day lacrosse, called baggataway.

Story telling was a favorite family activity that included young and old alike. The stories shared might be exciting, funny, scary, or sad. They were most certainly always entertaining, as the Haudenosaunee were known for their oratorical skills. Family elders used these stories to teach young people the secrets of successful living and the art of story telling, so that they might pass these things on to their own children. §

A child watches from his position tied into a cradleboard. Native American women used the device to carry their children while they worked at their daily chores: planting and cultivating crops, preparing meals, and making household items.