CHAPTER 1

FACING REALITY

“We have forgotten that the economy is a tool to serve the needs of society and not the reverse. The ultimate purpose of the economy is to create prosperity with stability.”1

SIR JAMES GOLDSMITH,

CEO, the Goldsmith Foundation, 1994

“While America’s super-rich congratulate themselves on donating billions to charity, the rest of the country is worse off than ever…. Millions of Americans are struggling to survive. The gap between rich and poor is wider than ever and the middle class is disappearing.”2

THOMAS SCHULZ,

Der Spiegel, August 19, 2010

“That was the old curve. Then I drew the new one. It curves down: wages don’t rise; you can’t get on the property ladder. Fiscal austerity eats into your disposable income. You are locked out of your firm’s pension scheme; you will wait until your late 60s for retirement…. This generation of young, educated people is unique—at least in the post-1945 period: a cohort who can expect to grow up poorer than their parents.”3

PAUL MASON,

The Guardian, July 2012

Americans have long been proud of their economy. And why shouldn’t we be? From the time we were children, we’ve been told that we live in the best country in the world, with the most expanding and dynamic economy. We’ve been told that our economy allows Americans to enjoy a lifestyle that is the envy of the world. And we’ve been told that we live in the home of the American dream, a country that—more than any other—allows people to rise up from poverty into the ranks of the rich. But is it really true?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. These things haven’t been true for a long time. But they used to be true.

In the period from 1946 to 1972, America experienced the longest and most robust period of wealth creation the nation has ever experienced. Year after year, the economy grew substantially. Productivity growth was equally dramatic. Businesses experienced strong profits, and employees experienced steady growth in wages. It was a golden age for America, and, throughout this book, I’ll refer to this period of time as the golden age.

Most of the major industrialized countries experienced similar growth. Because of the rebuilding after World War II, and the aid afforded by the Marshall Plan, many European countries grew even faster than the United States. Every country’s experience was unique, driven by their particular circumstances, but, overall, the trend was up. Economies grew, businesses thrived, and wages expanded.

Moving into the mid-1970s, America’s economic performance suffered. Stagflation—inflation combined with minimal economic growth—eroded wages and profits, weakening business and consumer confidence. Escalating energy prices and an overly loose monetary policy were the major causes. In August 1979, President Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Board of Governors for the Federal Reserve System. Volcker is widely credited with ending stagflation by tightening credit, and by 1983 inflation was back to a relatively healthy 3.2 percent. In November 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected president and took the economy in a dramatic new direction, a direction that, with some twists and turns, has continued to this day. Throughout this book, I call this new direction Reaganomics, in honor of the man identified most closely with this new economic direction. But Reagan isn’t alone. As we’ll see, Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton did very little to change this direction. President George W. Bush doubled down on Reaganomics, and President Barack Obama, amid a gridlocked Washington, has been stymied in efforts to change it.

We’ve been living under Reaganomics since the 1980s, a span I call the Reagan era. Please be clear that I’m referring to the entire period from 1980 until now, and not just the duration of Reagan’s presidency.

I’ll define Reaganomics in detail later in the book, but for now, this brief description will suffice. Reaganomics is a version of laissez-faire capitalism that emphasizes a minimum of regulation, especially in the financial sector; a lowering of taxes, especially on the wealthiest individuals; rapid growth in government spending, especially on national defense; and an indulgent attitude toward the business community.

The Impact of Reaganomics

Economists are critical of the overall impact of Reaganomics on productivity and family prosperity. Yet millions of ordinary Americans believe it has been a positive recipe for the country, a perspective I believe ignores the big picture. As we shall see throughout this book, Reaganomics has been unkind to most Americans.

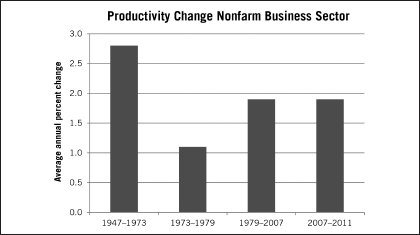

The failure of Reaganomics is not limited to income erosion. The growth in American productivity dropped precipitously over the Reagan era. Productivity growth is not discussed much in the United States (it is in some other countries, as we shall see), but it’s the single most important measure of economic performance. Productivity is commonly defined as total production divided by the number of labor hours. Raising productivity is the only way that inflation-adjusted salaries can increase on a per capita basis. During the golden age, productivity grew an average of 2.8 percent per annum; it slumped during the stagflation of the 1970s and then averaged a third lower, at 1.9 percent through 2011.

Chart 1.1.

Source: “Productivity Change in nonfarm business sector, 1947–2012, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/print.pl/lpc/prodybar.htm.

Despite the slowdown in productivity growth during the Reagan era, there was still room for both wages and profits to grow, although at more modest levels than in previous years. But that didn’t happen; average wages went flat or worse in the Reagan era. So where did the gains from rising productivity growth go? Virtually all of the gains flowed into corporate profits and into earnings at the very top of the income pyramid. To be precise, economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty have concluded that only 5 percent of earners enjoyed income gains exceeding inflation during the Reagan era, and most of that was concentrated in the earnings of the top 1 percent. That is why income disparities widened noticeably.4,5

Such a skewing of incomes over a span measured in decades is unlikely to be a chance event. Rather, it was the outcome of Reaganomics, a replay of the Gilded Age of the 1920s when the business community was also weakly regulated. Here is how Harvard professor Alexander Keyssar summarized Reaganomics:

“It’s difficult not to see a determined campaign to dismantle a broad societal bargain that served much of the nation well for decades. To a historian, the agenda of today’s conservatives looks like a bizarre effort to return to the Gilded Age, an era of little regulation of business, no social insurance and no legal protections for workers.”6

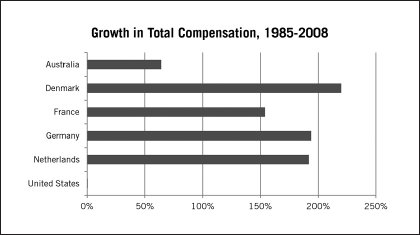

Pundits have come up with explanations for the economic outcomes of the Reagan era, including technological change and globalization. But these explanations make little sense when we consider that labor compensation in other rich democracies rose briskly.

Chart 1.2. Inflation-adjusted total labor costs per hour in dollars.

Source: “International Hourly Compensation Costs for Production Workers in Manufacturing (wages, all benefits, social insurance expenditures and labor-related taxes),” Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, http://www.bls.gov/fls/pw/ichcc_pwmfg1_2.txt, and “Private Consumption Deflators,” Economic Outlook No. 90, December 2011. OECD, Paris, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=32463#.

The problem with this line of reasoning is that other countries were also affected by these phenomena. Technology change impacted Australia. Germany, France, and Denmark are far more exposed to globalization than America is. Yet none of these countries experienced the stagnant wages that America is still facing.

The lesson is that the different outcome in America has nothing to do with these various economic forces like globalization. Instead, it has everything to do with the economic choices America’s leaders in Washington made in responding to these forces. They made different choices than leaders abroad, and so the outcomes were different. The experience abroad confirms that there is an alternative to Reaganomics. I call it “family capitalism,” and it’s what America practiced with great success in the decades following World War II.

The Alternative: Family Capitalism

Family capitalism, like Reaganomics, is based on free-market economics. But it recognizes that the market isn’t perfect. In particular, family capitalism:

▲ Understands the importance of selective government regulation, particularly in the financial sector.

▲ Puts a premium on long-term productivity growth.

▲ Recognizes and modulates the dangers of corporate influence on government.

▲ Puts a priority on long-term growth in wages as the key to family prosperity.

Based on the above principles, there are more than a dozen rich democracies around the globe practicing family capitalism. Because of data availability, I focus on eight of them: Austria, Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Throughout this book, we’ll compare the Reagan-era performance and practices of these eight countries with those of the United States. The results, I warn you, won’t be pretty.

I don’t claim that these eight countries all follow the same practices. They don’t. There are distinct difference in their economies and their politics, ranging from Sweden, where the government plays a very large role in the economy, to small-government Australia, which the conservative Heritage Foundation rates as “more free” than the United States.7 Even so, there is a similarity in economic policies and outcomes, which allows me to classify them all as Family Capitalist countries.

Further, I don’t claim that these eight countries get everything right. For example, all but Australia belong to the free trade zone embodied in the European Union, an alluring but incomplete concept that jeopardizes the future of the northern European economies. The lessons reviewed in this book are not related to these macroeconomic troubles, however, but are drawn from the internal mechanisms that Australia, Germany, and others successfully utilize to broadcast the gains from growth broadly among families within national borders. There are definitely things each of them can learn from American approaches. But, overall, the data on wage growth forces me to conclude that they get it right more often than we do. Once you review the data, I think you’ll agree.

Because most of the Family Capitalist countries are European, it’s easy to conclude this is a review of the big government aspects of northern Europe. Certainly, conservative politicians frequently caution Americans of the danger posed by the European social welfare state, and delight in accusing political targets of harboring secret ambitions to transplant that model to America. I am advocating no such thing, as the inclusion of low-tax Australia evidences. With the world’s highest median wealth, it shows that economic outcomes rather than the size of government are determinant in this book.8 As you will see, the lessons they offer have nothing to do with high or low tax rates or big or small public sectors. Moreover, family capitalism is as American as apple pie. It’s the system we practiced from the end of World War II until the 1970s, the most prosperous period of our nation’s history. If not invented here, America’s golden age certainly put wind beneath its wings as a goal eagerly adopted overseas.

How I Got Here

I bring a practical amalgam of training, background, and experience to the analyses of national economic goals and structure in What Went Wrong. My insight about the different outcomes in the United States and abroad was reached partly as a byproduct of helping establish a nonprofit organization in Europe to conduct medical research. Despite the ease of travel, few Americans beyond a tiny number of executives at multinational firms and banks have reason to develop familiarity with the Australian or northern European economies. And even fewer American scholars bother since the demise of the Cold War demoted the US study of comparative economic systems to an academic backwater.

My experiences over more than a decade of travel and consultation in Europe have provided a rare opportunity for a seasoned American economist with a background in international economic issues. I became immersed over this period in the structure, nuances, and current operation of the northern Europe economies, particularly their wage mechanisms, corporate governance, and labor market policies. I began applying typical professional standards of observation and analysis in gathering and synthesizing the information about the European economies presented here, later adding the Australian economy as well.

My career provided me a leg up in this analysis, beginning with several decades as an economist in the US Senate working for the admired Hubert Humphrey toward the end of his fruitful life. Later I joined Senator and then Treasury Secretary Lloyd Bentsen, a trade and tax expert. My work involved analysis of a wide variety of issues ranging from budgets to energy policy, taxes, and trade policy. And that experience broadened further during my several years early in the Clinton Administration at the Treasury Department. I worked primarily on budget issues involving international financial institutions including the International Monetary Fund (IMF); the development banks for Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia; and on international trade legislation (the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA). The months of work on NAFTA, in particular, sparked my interest in wages and outsourcing issues, which continued during my subsequent work at the World Bank. Work with the development banks provided me with an intensely useful education in the various models of capitalism across the globe.

After developing real estate projects for some years, I collaborated in 1998 with a senior official at the Institute of Medicine, in crafting an innovative concept to stimulate the development of medicines for neglected tropical diseases. That process included a period of conferences and meetings abroad, with the concept eventually being embraced in 1999 by the international aid group Doctors Without Borders.9 Several years of collaboration followed as the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative took shape.

Helping establish a nonprofit in Geneva with a €15 million budget and serving over the last decade on its audit committee involved considerable research of and exposure to uniquely European wage and business practices. I learned firsthand the nuts and bolts of European capitalism, an education that took on a life of its own. It has become enriched in the years since with serious scholarship, a heavy dose of statistics, and interaction with international financial and labor economists. That has enabled me to take the full professional measure of the starkly different economic goals and wage determination schemes in Reagan-era America and in the family capitalism countries.

The bottom line is this: Voters in nations such as Germany, the Netherlands, or Australia expect everyone—from the corner grocer to government officials and corporate CEOs—to prioritize family prosperity. They demand government standards and rules that prioritize rising wages nationwide, quality education and upskilling opportunities, and the creation and maintenance of high-quality jobs. Enterprise serves families—not the other way around. The three most important topics on voters’ minds are: wages, productivity, and how much of the rise in labor productivity growth flows to families.

While the family capitalism countries are rich democracies like the United States, their goals and outcomes are so dissimilar from America since the 1980s that they seem to be operating on different planets, as you will see.

Can This Be Right?

This book argues that, beginning in the 1980s, America took a wrong turn. That is why, over the next thirty years, our economy has delivered substantially less to its citizens than the eight family capitalism countries that avoided the pitfalls of Reaganomics.

That may be difficult to accept. Virtually every American has grown up believing in the superiority of our economy. We’ve felt almost contemptuous of “old Europe” and its sclerotic economic system. Surely these countries cannot be delivering what America has not—higher wage growth, higher productivity growth, and more economic opportunity?

I’ll begin making this case by addressing several issues.

First, the statistics I use are publicly available through US and foreign government agencies, including: the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the IMF, United Nation agencies, peer review professional journals, and books by respected economists from Niall Ferguson to Paul Krugman.

Second, I conclude that families in the family capitalism countries have economically overtaken American ones, a puzzling assertion since American Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is higher. Like oil-rich Norway or banking center Luxembourg, US GDP per capita is higher than the family capitalism countries, but that reveals nothing about whether that output translates into compensation for ordinary employees and families. Indeed, all nonpartisan economists acknowledge that growth in the economy since the 1980s has gone almost entirely into corporate profits and the incomes of the very richest Americans. Having relatively large energy and banking sectors adds to US GDP, but only a portion is translated into wages.

Third, some might argue that this skewed allocation of the gains from growth is temporary. The major principle of Reaganomics is that by freeing up business to maximize profitability, wealth will be created, which—ultimately—will benefit all. If you are old enough to remember the beginning of the Reagan era, you’ll recall that this was once called “trickle-down economics.” Well, thirty years on, most families are still waiting for trickle down to deliver.

It’s Not Reaganomics, It’s Globalization

Another argument is that globalization and outsourcing of jobs, not Reaganomics, are responsible for weak wages. But as I noted previously, this argument is belied by the experience of the family capitalism countries. In fact, globalization strengthens my argument. Due to the relatively high international trade intensity of the family capitalism countries, globalization has impacted them much more severely than the United States. So the difference must not be in globalization itself, but in the policies crafted in reaction to it.

The unfettered international flows of capital, technology, and goods characteristic of global integration have dramatically improved global economic efficiency. Overall, this is a good thing. But the American experience demonstrates that those same forces pose an existential threat to the high wages and living standards of the rich democracies if not remediated. This book reveals that policies to ameliorate the dangers of globalization and to maximize its benefits can succeed. And the evidence is provided by the different outcomes of policies pursued during the Reagan era by an indifferent Washington in contrast to policies by leaders in cities like Berlin, Canberra, Copenhagen, Paris, and Vienna.

Washington officials in the throes of Reaganomics refused to ameliorate the forces of global integration, leaving families like deer in the headlights; they abandoned American families to become mere commodities in hostile labor markets. Washington rejected intervention, such as reformed corporate governance or upskilling of workforces, to instead honor the dictates of the marketplace as interpreted by US multinationals and Wall Street. The impact on virtually all Americans was severe.

The erosion in US wages is mostly a consequence of quite profitable firms across America demanding large-scale wage and benefit concessions across the board, freezing total employee costs in real terms, adjusted for inflation. Nearly unique among rich democracies, American executives have been on a tear for decades, aggressively capping employee costs because—well, because they can. For a while, rising outlays for health care and other fringe benefits offset some of the wage erosion, but that ceased to be true nearly a decade ago. In contrast, overseas in the family capitalism countries (and during the golden age in America) there is an aversion by healthy companies to arbitrarily freezing or lowering the compensation of good employees.

For example, the beverage conglomerate Dr. Pepper Snapple Group in 2010 demanded $3,000 wage concessions, froze pensions, and reduced fringe and health care benefits at its Mott plant in Williamson, NY. These givebacks were demanded despite Dr. Pepper Snapple earning profits of $555 million in 2009 on sales of $5.5 billion, an enviable 10 percent profit margin during a soft year.

Like many other US employers now, Dr. Pepper Snapple didn’t bother even to intimidate employees by threatening to export jobs. Instead, the company warned of hiring replacement workers for as much as one-third less from the same Williamson area. The message was take it or leave it. What happened to the costs savings from these lower wages? Dr. Pepper Snapple increased its dividend by 67 percent in May 2010.10 Indeed, the profits of Dr. Pepper Snapple are indicative of a remarkable aspect to this dispiriting wage trend of the Reagan era. Families have experienced falling wage offers from profitable firms for the first sustained period ever in American history; yet voters, and thus Washington officials, appear indifferent to highly profitable firms like Mercury Marine or Harley-Davidson cutting wages to bolster profits.11

With little public debate, Washington policy allowed American jobs to become disposable, which allowed family prosperity to become vulnerable. Iconic firms like Apple shifted millions of jobs to cheap and subservient labor forces abroad willing to work 12-hour, six-day-a-week schedules, the ideal docile and disposable labor force in the eyes of Reagan-era American executives. This outcome was facilitated by the pecuniary foundation of US politics and an increasingly marginalized trade union movement.

When challenged, firms that have exported jobs obfuscate the facts. When the impact of offshoring jobs is pointed out, executives frequently blame the victims. They blame American employees. As an example, one Apple executive mendaciously justified his Chinese labor force this way: “The US has stopped producing people with the skills we need.”12 Well, it’s theoretically possible that Apple is really responding to the superior training of Chinese workers, rather than their $145 per month salaries, but I seriously doubt it.

In contrast, the family capitalism countries were proactive, prospering despite the tumult of global integration. They rejected trade controls, the commoditization of workers, and market fundamentalism in favor of canny mechanisms to maximize productivity and family income growth. Unhampered by ideology and buttressed with centuries of vigorous economic debate between the likes of Adam Smith and Friedrich Hayek, they focused on meeting election mandates demanding family prosperity.

It wasn’t that difficult to accomplish, because these rich democracies came armed to the existential struggle with better tools than America. They have political systems dominated by voters instead of donors, a superior hyper-competitive corporate governance structure, and an electorate strongly appreciative of the wealth free trade creates and keenly sensitive to the role of wages in driving the prosperity of the family.

Leaders in these nations reacted with dispatch, transforming the dangers of global integration into broadly based prosperity. Protectionism was avoided and even aggressively attacked when identified abroad. These nations didn’t experience an American-style stagnation of wages and offshoring of jobs. Instead, Australia and northern Europe pursued policies informed by the best and brightest trade economists of our age.

Drawing on the theories of David Ricardo, for example, economists Paul Samuelson and Wolfgang F. Stolper had concluded as early as 1941 that international trade creates long-term losers as well as winners. So leaders abroad crafted remediation: a balance of clever mechanisms maximizing the gains from globalization and broadcasting those gains to families, while minimizing its harm to jobs and wages.

This reality reveals the hollowness of complaints by American firms such as Apple that routinely warn about high American labor costs and mediocre skill levels. Adam Smith, whose book, The Wealth of Nations, marked him as the father of capitalism, had heard the same thing when writing back in the eighteenth century. Like today, profits were high, but British business leaders in 1776 nonetheless vented about high wages harming sales. Smith would have none of it.

“Our merchants and master-manufacturers complain much of the bad effects of high wages in raising the price, and thereby lessening the sale of their goods both at home and abroad. They say nothing concerning the bad effects of high profits. They are silent with regard to the pernicious effects of their own gains. They complain only of those of other people.”13

In the end, we are forced to conclude that the gap between US outcomes and those of the family capitalism countries is real. It isn’t an artifact of the data. It isn’t a sensible tradeoff between conflicting beliefs. It’s not a short-term problem that will go away. And it’s not an inevitable result of globalization. The United States simply made a fundamentally wrong turn. What could have been a temporary sidetrack became the main track—and American families are still paying the price decades later.