CHAPTER 6

A CULTURE OF SELFISHNESS

“Stock-based compensation plans are often nothing more than legalized front-running, insider trading, and stock-watering all wrapped up in one package.”1

ALBERT MEYER,

Founder, Bastiat Capital

“If a worker’s rewards are based on only some of her tasks, that is where she will concentrate her effort. For example, a CEO whose compensation depends on the current stock price will try to run up the current stock price, but will ignore the long-term consequences.”2

GEORGE AKERLOF and RACHEL E. KRANTON,

Identity Economics, 2010

“If the absolute value of every top earner’s take-home pay were to fall by half, the same executives would end up in the same jobs as before.”3

ROBERT H. FRANK,

Cornell University

“Management has become obsessed with share price. By focusing on short-term moves in stock prices, managers are eroding the long-term value of their franchises.”4

JESSE EISINGER,

New York Times, June 28, 2012

There are two secrets about shareholder capitalism:

First, shareholder capitalism presumes that firms maximize profits. The truth is, it seems that relatively few firms do that. Many CEOs actually have only vague notions of exactly how to maximize profits.

Second, it turns out not to matter because of the next secret: the real goal of management is maximizing executive compensation.

I’ll let Justin Fox of the Harvard Business Review and Harvard professor Jay Lorsch explain:

“Conflict between shareholders and managers is asymmetric warfare, with shareholders in no position to prevail.”5

Because of management’s ability to control information, it was inevitable that shareholder capitalism would devolve to managerial capitalism, where enterprises in Reagan-era America neither maximize profits nor maximize shareholder returns. That has made shareholder capitalism useless as an operational philosophy.

The Myth of Profit-Maximizing Enterprises

During the golden age, US executives were paid modestly, with the rare outstanding performance rewarded with bonuses or higher salaries. Compensation was important, but so were other issues. That changed in the Reagan era. Firms nominally became profit maximizers, ostensibly managed solely for the benefit of shareholder-owners. And that outcome was to be accomplished by linking executive compensation to profits. This conceptualization of shareholder capitalism argued that management should pivot from the golden age ethos of prioritizing profits along with community and employee goals to a sole focus on profits. And it is certainly true that profits have risen sharply. But one of the first rules of economics is to follow the money. And that trail teaches us that profits and share prices have risen much less than executive compensation. Management—not shareholders—has been the big winner in Reaganomics. Indeed, economists have determined that executives don’t even bother to maximize firm profits.

The extensive research documenting this reality has been unkind to Milton Friedman’s 1953 dictate that profit maximization should drive executive suite behavior:

“Whenever this determinant happens to lead to behavior consistent with rational and informed maximization of returns, the business will prosper and acquire resources with which to expand; when it does not, the business will tend to lose resources and can be kept in existence only by the addition of resources from outside.”6

Friedman’s market determinism has been discredited. Indeed, it’s unlikely that executives could manage to maximize profits instead of executive compensation even if actually interested in doing so. A large body of management and behavioral economics research has documented that, lack of motivation aside, guiding firms turns out to be too nuanced and demanding for managers to behave ideally and consistently, as Friedman suggests. Economists Mark Armstrong and Steffen Huck of University College London, for example, concluded in 2010 that executives are little better than consumers at resisting herding and other economically irrational human tendencies.

“We present evidence—both real world and experimental—that firms … sometime depart from the profit-maximizing paradigm. For instance, firms may be content to achieve ‘satisfactory’ rather than optimal profits, firms might rely on old patterns—such as imitating the strategies of well-performing rivals, or continuing with strategies which have performed reasonably well in the past—rather than on explicit calculations of complex optimal strategies….”7

Maximizing short-term executive pay, reputational preservation, maintenance of market share, fear of hostile takeovers, friendship or annoyance with peers, or a fiercely competitive streak: all these concerns and behaviors produce suboptimal profits. That occurs also when management adopts the goal of Wall Street analysts and targets profit growth rates relative to rivals rather than to absolute profits. Or they may pointlessly price too aggressively, perhaps signaling an eagerness to discourage potential competitors from entering their market. Suboptimal outcomes are also common because management resorts to shortcuts and rules-of-thumb in dealing with their highly complex and uncertain environment. Moreover, it is simply too time consuming to determine where the profit-maximizing intersections of marginal costs and marginal revenues rest for hundreds of products in hundreds of overlapping markets, each with unique dynamics.

Far worse, it turns out that even the most informed, analytical, and competent American executives have not even bothered to clarify the proper data set required for profit-maximizing production and pricing. CEOs tend to base pricing decisions on sunk or fixed costs, even though economists have long taught MBA students that profit-maximizing price and output decisions should be dictated by marginal revenues and costs. As early as 1939, it was realized that this seminal rule is broadly flouted and may not even be known by many executives. The shift to shareholder capitalism should easily have rectified the problem, but did not. Studies as recent as 2008 confirm that this same suboptimal behavior persists, with pricing decisions by a majority of managers including considerations of fixed or sunk costs.8

Ignorance and inadequate information aside, the existential fallacy in Friedman’s philosophy is that enterprise executives are the major beneficiaries of the shift to market fundamentalism in recent decades, not shareholders or anyone else, especially not the firms they manage. Management maximizes enterprise profits beyond the immediate quarter almost by happenstance. And it is not at all unusual for enterprise leaders to mismanage firm assets, diminishing rather than enhancing longer-term firm profit prospects. These suboptimal outcomes have been most commonly identified with undue self-confidence, a typical behavioral trait of survivors in the US executive-suite derby; it makes CEOs too quick to launch ill-fated takeovers or mergers, for example, simply because they view them as likely to spike quarterly results.

Perhaps the most prominent research on this and other aspects of contemporary managerial irrationality dates from 1986, when economist Richard Roll linked such excessive merger behavior with executive suite overconfidence.9 Other researchers agreed. Over-projecting the synergistic benefits of acquisitions “could therefore be one explanation for why companies which undertake mergers seem to underperform,” noted the University College London economists Armstrong and Huck. Indeed, they concluded that there were a number of similar factors causing underperformance: “We see there are several situations in which Friedman’s (1953) critique of non-profit maximizing behavior appears to fail.”10

Managerial Capitalism

Walmart CEO Michael T. Duke is in a great hurry to open new stores. You see, his bonus is in jeopardy. In the past, the bonus was tied to same-store sales, which is the only accurate way to measure firm and management performance. But sales at existing stores are slumping. Duke’s solution? Insist that his board of directors put their thumbs on the scale: replace Duke’s bonus plan with one linked to total companywide sales, helpfully bloated by opening new stores in nations like Mexico.11

Despite being quite capable, American executives get a lot wrong today, as we are about to learn. But one thing all of them get right is superbly gaming the dysfunctional American system of corporate governance to enhance compensation while compressing wages, R&D, and investment.

We know that from sentiments of corporate leaders like GE CEO Jeff Immelt. By July 2009, he had grown embarrassed by the narcissism of American executives: “I would hate to think that the lasting impression of this generation of American business is the one that exists today.”

Former New York Times reporter David Cay Johnston noted that the new pattern of compensation that emerged with the Reagan administration is exemplified by the earlier GE CEO Welch, “whose way was to squeeze the pay and numbers of the rank and file and then richly reward executives.” Welch mentored many executives, such as John M. Trani, who subsequently endeavored to move the Connecticut firm Stanley Tools from New Britain to Bermuda to avoid paying US taxes. Johnston described the archetypal new manager Trani this way:

“He was part of a new era of corporate managers, many of them Welch acolytes, who never shook hands with anyone who got grease on theirs, even if they had wiped them clean when their one big chance came to meet the boss. They neither mingled with the people who made their company products nor did they appear to think much about their lives.”12

Was the Creation of Managerial Capitalism a Conspiracy?

A conspiracy?

It’s tempting to ascribe rising executive pay and US income redistribution since 1980 to a vast conspiracy, but it is not. Rather, it is the outcome of the business community becoming intellectually willing and politically able as Reaganomics unfolded to pursue narcissistic self-absorption in the best traditions of nineteenth-century robber barons. And no one, especially shareholders or employees, was permitted to stand in its way.

History records that the Reagan era was just the latest of America’s Gilded Ages. The first episode occurred in the three decades after 1880, when entrepreneurs such as Pierpont Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and John Jacob Astor emerged. They seized upon the quack pseudoscience offered by Yale professor William Graham Sumner, Herbert Spencer (Social Statics, 1851), and others in the afterglow of Darwinism to justify widening income disparities. Great wealth is the imprimatur of mankind’s most evolutionary fit, and the means for such evolutionary superiority to be perpetuated. This pseudoscientific logic helped assuage any guilt and deflected brickbats from critics such as Mark Twain.

During the Reagan era, similar pseudoscientific rationale was provided by the themes of shareholder capitalism, and especially by Ayn Rand. The outcome is that business leaders are constantly driving one another to garner more income. As Diane Coyle, visiting professor at the University of Manchester, wrote:

“[The] banking bonus culture validated making a lot of money as a life and career goal…. Remuneration consultants … helped ratchet up the pay and bonus levels throughout the economy.”13

“Too much” became “never enough.” In hindsight, it’s clear that CEOs pursuing their own magnified self-interest within this new environment enabled business leaders to engage in de facto class warfare as they strove to seize a larger share of the gains from growth. But class warfare was the last thing on their minds. Like the John Laws of yesteryear, their motivation was simply to increase their incomes at anyone else’s expense.

They succeeded in stagnating wages, lowering taxes, slowing investment, and weakening the social safety net—never mind the long-term interest of shareholders, the urgency of driving productivity, or the tens of millions including children lacking health care or bedding down hungry every night in their own cities. Most seem indifferent to the reality that one of every two American children will need food stamps at some point or that tens of millions live on the margins in a shadowy economic netherworld, much like subsistence farmers in some far-off, developing nation. The business community looks right through those Americans.

This pattern is sufficiently stark that the psychological framework supporting such callous behavior in robber baron periods has become a fascination for social scientists parsing the relationship of socioeconomic class and unethical behaviors. This includes researchers like Paul K. Piff at the University of California, Berkeley, lead author of a study published in the February 2012 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.14 In a series of elaborate experiments, Piff and his colleagues found a consistent difference in the reaction to ethical situations between middle- and working-class participants and upper-class participants; upper-class subjects routinely exhibited greater selfishness and unethical behavior. Displaying a sense of entitlement, upper-class folks proved more likely to lie and cheat, among other pathologies; they stole twice as much candy from children; readily deceived job candidates by withholding important information (e.g., the job was only temporary); and cheated by embellishing their scores in self-reporting competitions.

“The increased unethical tendencies of upper-class individuals are driven, in part, by their more favorable attitudes toward greed,” concluded Piff. Relatively indifferent to community standards, “Upper-class individuals are more self-focused, they privilege themselves over others, and they engage in self-interested patterns of behavior.” Sound like anyone you know or have read about?

Dysfunctional Corporate Boards of Directors

Recall the imagery of the pigs greedily exploiting the effort of others in George Orwell’s Animal Farm? A genuine and faithful incarnation is the behavior in recent decades of American executives colluding with colleagues on corporate boards of directors.

Supervisory oversight of CEOs has historically been weak in America, where boards have traditionally been widely held to be ineffective.15 But the opportunity for windfalls during the Reagan era caused traditional supine board governance to deteriorate even further. Too many CEOs are able to pick their own boards: board elections feature a management-selected list of candidates, with critics facing daunting expense and administrative barriers to landing positions on the ballot. Only rich corporate raiders like William A. Ackman of Pershing Square Capital Management can compete. Journalist Ian Austen explains:

“We forget how unusual the corporate election system is in a democracy. Ninety-nine percent of the time, shareholders are not given a choice as to who they wish to represent them on the board of directors.”16

Firm performance would benefit from visionary and even contentious boards rather than incurious ones. Instead, CEO friends and cronies are appointed to boards. CEOs also tend to join other boards, readily approving handsome compensation packages, using a practice economists term peer-benchmarking. CEO compensation is routinely set at the 90th percentile of peer firms for CEOs like Angelo Mozilo at (bankrupt) Countrywide Financial. That scheme creates an automatic escalator in executive pay.

How incestuous are board-CEO relationships? Well, a survey involving 350 of the firms comprising the S&P stock indices over 15 years by University of Michigan business professor James Westphal found that nearly 50 percent of compensation committee board members were identified by CEOs as “friends” rather than acquaintances.17 Such custom-crafted boards routinely tolerate mediocre or worse performance. Examples abound.

Amgen CEO Kevin W. Sharer finally resigned in May 2012, but his annual compensation had increased 37 percent to $21 million over his years of service—despite shareholders losing 7 percent. One of the firm’s largest shareholders, Steve Silverman, complained to Peter Whoriskey of the Washington Post in 2011:

“Members of the Amgen board are basically just rubber-stampers. Kevin put most of them on the board himself. If he’s getting paid too much—and he certainly is—they’re not going to say so.”18

A particularly egregious example was the antics of board members at Merrill Lynch in 2007. Bankrupt and headed for a fire sale at pennies on the dollar, they inexplicably decided to let the incompetent CEO, E. Stanley O’Neal, resign instead of firing him. In doing so, they dinged shareholders for $131 million in stock options O’Neal would otherwise have forfeited.19

Another example is reported by David Cay Johnston in his book Perfectly Legal, involving Eugene M. Isenberg of Nabors Industries, a large oil-drilling firm. In 2000, that firm reported sales of $1.3 billion. Amazingly, through a combination of stock options and a well-crafted compensation agreement, Isenberg received $127 million of that cash flow, or nearly 10 percent of gross revenue.20

And, there is Craig Dubow. Dubow was CEO of the media giant Gannett for six years, which ended with his resignation in 2011. It was a lush run for him: Dubow received a golden parachute worth $37.1 million, plus $16 million in cash during just his last two years. Yet, Dubow’s record was poor, with share price falling from $75, when he arrived, to $10.21

Board members supporting CEOs like these covet the relationships, perks, and pay; median remuneration for nonexecutive board members at Fortune 500 firms was $199,949 in 2008, according to the compensation firm Towers Perrin.22 Moreover, most are incurious, because few have significant personal wealth linked to their companies, while opaque board proceedings, and directors- and officers-insurance shield them from personal liability, even in bankruptcy. Compensation experts John Gillespie and David Zweig, authors of Money for Nothing, note that there were a bare 13 instances between 1980 and 2006 when outside directors settled suits with their own personal resources. Even then, punishment was mild: Enron directors “paid only 10 percent of their prior net gains from selling Enron stock.”23 Remarkably, their careers also seem unaffected by the Enron connection; four served on other boards, one taught at Stanford, and another became Chancellor at London’s Brunel University. Wendy Gramm? Well, she has resided at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, supported in part by donations from the Koch brothers (who preach there should be penalties for market failure).24

CEOs enjoy celebrities and so have tended to appoint them to boards. That’s why boards too often look like an American version of Debrett’s Peerage or at least Dancing with the Stars. The list of board members has included Lance Armstrong, skier Jean-Claude Killy, Tommy Lasorda, Fran Tarkington, and even Priscilla Presley and O.J. Simpson (on the audit committee at Infinity Broadcasting). The Lehman Brothers board included actresses, theater producers, and a retired admiral. This trend has abated in recent years with boards under more scrutiny. Yet, the innate collegiality of US board members limits contention. As Gillespie and Zweig note, board members:

“… don’t want to appear foolish by asking questions. Others don’t want to rock the board for fear of ostracism. Sometimes the desire for collegiality seems much more immediate than the need to represent shareholders who are not in the room.”25

One problem is that too many members are unqualified, lacking industry, financial, or investment expertise. Folks with excellent people skills, but lacking skill in complex financial matrices, are particularly ill-suited members. A second problem is conflicts of interest. A common technique to ensure deferential boards is for CEOs to flout the intent of NASDAQ rules that require a majority of members to have limited or no company ties. A designated “independent” member of Rupert Murdock’s News Corporation’s board, for example, is the former CEO of Murdock’s Australian subsidiary, News Limited. Another is a godfather to a Murdock grandchild. And virtually all of his board members owe careers or wealth to Murdock’s enterprises.26

The independence of such boards is nominal. Experts such as Harvard law professor Lucian Bebchuk (also director of the Harvard Program on Corporate Governance) and economist Jesse Fried are highly critical of boards for their routine endorsement of lush compensation packages for CEOs. In a 2010 analysis, for example, they concluded compensation is not set at arm’s length by such boards, but instead that CEOs essentially manipulate boards to set their own pay:

“Directors have had various economic incentives to support, or at least go along with, arrangements favorable to the company’s top executives. Collegiality, team spirit, a natural desire to avoid conflict within the board, and sometimes friendship and loyalty has also pulled board members in that direction…. Indeed, there is a substantial body of evidence indicating that pay has been higher, or less sensitive to performance, when executives have more power over directors…. Executive pay is also higher when the compensation committee chair has been appointed under the current CEO …”27

Here is a February 2010 editorial by the feisty Financial Times discussing the result of high pay:

“There is no evidence that such packages promote exceptional performance—and much to suggest they destroy the social fabric of companies as the gap between chief executives and workers soars. The clubby remuneration committees behind these preposterous packages deserve to be slung out on the street.”28

Why has the American system of supine boards persisted? An important factor is they have been credentialed by academics such as Harvard business professor Michael C. Jensen. Like Milton Friedman, who provided a veneer of intellectual gravitas for Reaganomics, Jensen’s musings on Harvard stationery have lent a patina of respectability to a compensation system riddled with conflicts of interest and market failure, with pay disconnected from performance. He wrote several academic papers in the 1980s credentialing stock options and the extremely high executive compensation they produced. Some academic colleagues disagreed, and so Jensen and a coauthor, University of Southern California professor Kevin J. Murphy, wrote in the New York Times in May 1984:

[Readers] “… must be wary of wolves dressed in sheepskin currently attacking executive compensation to achieve their own ends. Many assert that executives are overpaid and paid in a way that is independent of performance.”29

The embarrassment for Jensen and Murphy is that their academic critics have been proven correct. (To their credit, they had come by 1990 to agree with critics.) The consensus is explained by Gillespie and Zweig:

“Our initial inquiry into why so many boards seem to have failed led us quickly to this realization: … It is as if the American economy has been driving a race car without having the slightest idea of how a steering wheel works—not to mention the brakes…. Although it’s not supposed to be the case, most CEOs exercise powerful control over their boards. They dictate or greatly influence the directors’ selection and compensation, they set the boards’ agendas and committee assignments, and they control access to information. Thus, many boards come to represent executives’ interests rather than those of the shareholders.”30

Critics of board governance also included prominent conservatives such as Richard A. Posner, the federal appeals court judge quoted earlier, who has acknowledged that the market for executive compensation is dysfunctional. Writing in a 2008 dissent to a decision by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Jones v. Harris Associates, Posner concluded, “Executive compensation in large publicly traded firms often is excessive because of the feeble incentives of boards of directors to police compensation.”31

Think of the scope of the problem in weak corporate governance this way: behind every single report in the media of CEO pay not reflecting performance is a dysfunctional board. An apt analogy is the cozy search conducted by Richard Cheney for a vice presidential candidate to join Governor George W. Bush’s ticket in 2000. The outcome resembled events surrounding the antics of the board in recent years of the giant computer company Hewlett-Packard. Meg Whitman’s selection as the new CEO in 2011 was “secretly engineered” by a single board member “without putting the board or the company through the time and expense of conducting a proper search or seriously considering other candidates,” explained economics reporter Steven Pearlstein of the Washington Post.32 As Stanford law professor Donohue subsequently noted, “After what HP had gone through, you’d think the board would have been on their toes rather than asleep at the switch again.”33

Bonuses and Stock Options Are Accelerants in Rising Executive Pay

Since the 1980s, stock options have offered management the prospect of bountiful windfalls. But despite the whiff of greenbacks in the air, there was an asterisk. Those windfalls hinged on constantly improving earnings per share from one quarter to the next. It took only a New York minute for CEOs to figure it all out at the dawn of the Reagan era: management should ignore what they had been taught in business schools about focusing on productivity growth and longer-term investment, and abandon the principles that had guided American enterprise and economy in the wondrous decades after World War II. Instead, to personally strike gold, they needed to spike earnings per share over the next 90 days.

The easiest way was to switch corporate outlays from expenses (such as wages and R&D) to share buybacks and risky mergers. For American executives, the long term abruptly crystallized at three months. At the same time, management quickly mastered the trick of obfuscating and rendering opaque the system of option awards and bonuses. Australian journalist Ian Verrender explained the conjury this way:

“From an executive point of view, the brilliance of the bonus system is its sheer complexity. Each company employs different systems, imposes different hurdles, and arbitrarily alters them when conditions require.”34

Recall that senior American executives during the golden age earned about 30 times the average pay of their employees. Management pay was stable for decades before accelerating as the Reagan era unfolded, with that multiple rising to more than 300 times average employee wages now. In inflation-adjusted dollars, as depicted in Chart 6.1, compensation for the top three executives has increased fivefold since the 1980s, while real employee compensation went flat. It is now typical for a handful of senior executives at sizable firms to each average $5 million in annual pay, including bonuses and the value of stock options. Here is a startling statistic: CEOs now receive 10 percent of all corporate profits, according to Gillespie and Zweig.35

Chart 6.1. Median executive compensation received by the top three officials at the fifty largest US firms. Compensation includes salary, bonuses, long-term pay, and stock options based on the Black-Scholes value calculation of option grants.

Source: Carola Frydman and Raven E. Saks, “Executive Compensation: a New View from a Long-Term Perspective, 1936-2005,” Figure 1. Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill, Creating an Opportunity Society, Brookings Institution Press, 2009, Figure 3-10.

This new breed of American executive was quickly fingered by observers in the family capitalism countries. Here is columnist John Kay of the Financial Times in November 2009 looking back on this era:

“America has a new generation of rent-seekers. The modern equivalents of castles on the Rhine are first-class lounges and corporate jets. Their occupants are investment bankers and corporate executives…. The scale of corporate rent-seeking activities by business and personal rent-seeking by senior individuals in business and finance has increased sharply. The outcome can be seen in the growth of Capitol Hill lobbying and the crowded restaurants of Brussels; in the structure of industries such as pharmaceuticals, media, defense equipment, and, of course, financial services; and in the explosion of executive remuneration.”36

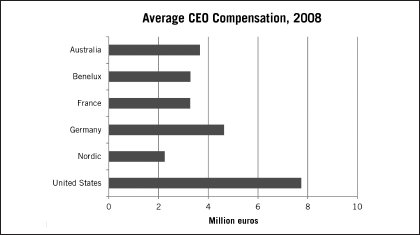

Exploding American executive pay is sharply at odds with pay patterns in any other rich democracy. Executive pay in most democracies, such as Germany, has risen far less during the Reagan era. Even in the Anglo-Saxon countries of Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, increases are dwarfed by the American experience.

The closest pay scale to America appears to be CEOs at the 100 largest firms on the United Kingdom’s major stock exchange (FTSE 100), where pay averaged 88 times employee wages in 2009.37 Elsewhere, Australian journalist Verrender notes that altogether, the top 14 executives of Japan’s biggest bank, Mitsubishi UFJ, were paid a total of $8.1 million in 2008—while Morgan Stanley CEO John Mack alone received $41.4 million in 2007 (Mitsubishi owns 21 percent of Morgan Stanley).38 Even at the most profitable firms in the world such as VW-Audi-Porsche in Europe, compensation is well below America.

The pattern is the same all across northern Europe. The CEO of Statoil, the giant Norwegian oil company, Helge Lund, for example, was paid about $1.8 million in 2010, with no share options, while Rex W. Tillerson, CEO at Exxon Mobil, received $21.7 million in 2009, including options. Tillerson’s pay alone is more than double the top nine Statoil executives combined, but is certainly not justified on pay-for-performance criteria. Statoil’s annual stock appreciation has averaged twice that of Exxon Mobil for the last decade.39

Overall CEO compensation levels in the family capitalism countries are a bit less than one-half American levels. Data gathered by the management consulting firm Hewitt Associates on remuneration for the year 2008 is reproduced in Chart 6.2.

Chart 6.2. 2010 Australia.

Source: Yann Le Gales, “French Officials Are Paid Less Than Others,” Le Figaro, March 5, 2010, and “Laws to Curb Executive Pay Soon,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 26, 2011.

Remuneration figures like these have captured voter attention abroad in nations including the United Kingdom and Australia. The concern is both with the level of pay and with the apparent disconnect between pay and performance. Even the silk-hat British Institute of Directors concluded in 2011 that “the legitimacy of UK business in the eyes of wider society is significantly damaged by pay packages that are not clearly linked to company performance.”40

The reaction to rising paydays has been stronger in Australia, where aggressive voters pushed back against large pay awards and succeeded; a 2011 law provides shareholders with the ability to readily spill or fire offending boards over executive pay. Voter attitudes there are exemplified by the journalist Verrender, writing in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“The idea that the exponential growth of corporate salaries is a global phenomenon, and that Australia has no option but to keep pace or lose top management talent, is a myth. It is an outright distortion of facts. The corporate salary race is a purely Anglo phenomenon, confined to North America, Britain, and Australia. European and Asian executives, even those running multinational corporations, are paid a fraction of the salaries paid in the Anglo sphere.”41

CEO Lemons: The Collapse of Pay-for-Performance in America

Foreign scholars describe American firms as providing “pathological overcompensation of fair-weather captains.”42 They are correct: the rise in US executive compensation of recent decades is unjustified by any performance metric, vastly outstripping indices like sales, profits, or returns to shareholders. The Clinton administration’s Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich, unearthed the smoking gun evidence:

“By 2006, CEOs were earning, on average, eight times as much per dollar of corporate profits as they did in the 1980s.”43

A vast disparity like this in trend lines is powerful evidence that executive pay suffers from market failure. There are many instances where genuine value for shareholders has been produced by well-run or visionary executive suites, justifying higher compensation. But examples abound, especially of late on Wall Street, where weak executives have also received lush compensation. Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf discussed this failure, focusing on the financial sectors in the United States and the United Kingdom, where investment management presents

“… a huge ‘lemons’ problem: in this business it is really hard to distinguish talented managers from untalented ones. For this reason, the business is bound to attract the unscrupulous and unskilled, just as such people are attracted to dealing in used cars (which was the original example of a market in lemons)…. Now consider the financial sector as a whole: it is again hard either to distinguish skill from luck or to align the interests of management, staff, shareholders, and the public. It is in the interests of insiders to game the system by exploiting the returns from higher probability events. This means that businesses will suddenly blow up when the low probability disaster occurs, as happened spectacularly at Northern Rock and Bear Stearns.”44

The syndrome is generalized across the entire American economy, and certainly not restricted to the financial sector. Indeed, a host of studies have caused compensation experts to conclude that much of the rise in executive pay across all sectors in recent decades is unjustified by performance. Their conclusions are encapsulated in this April 2011 editorial in the Financial Times:

“‘Pay for performance’ often turns into pay without performance. Incentives are easy to game and can undermine people’s intrinsic motives for doing a good job.”45

Scholars examining the failure of pay-for-performance include Virginia Commonwealth University economists Robert R. Trumble and Angela DeLowell:

“There is an inherent problem with this reward structure, though, as stock value may rise and fall independently of CEO influence…. In fact, no consistent connection has yet been made between CEO pay and corporate performance levels as measured by financial indicators such as stock price, profits, and sales.”46

Professors Alex Edmans from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania and Xavier Gabaix from the Stern School of Business at New York University concluded similar research in 2010 by noting, “Many CEOs are richly paid, even if their performance has been poor.”47 The iconic compensation expert Graef Crystal in 2009 examined the pay of 271 CEOs, using formulas he devised during his 30 years as compensation consultant to Fortune 500 firms like CBS and Coca-Cola. “Simply put, companies don’t pay for performance.”48

University of Southern California economist Murphy reached the same conclusion. While at the University of Rochester in 1990, Murphy and Jensen of Harvard parsed a database of 2,505 CEOs at 1,400 large firms over the period 1974 to 1988; they found that “in most publicly held companies, the compensation of top executives is virtually independent of performance…. Annual changes in executive compensation do not reflect changes in corporate performance.” For every $1,000 rise or fall in company value, for example, they found that CEOs received or lost a scant $3.25—a tiny 0.00325 percent equity link.49

Murphy recently updated his analysis by evaluating pay-for-performance of the top-earning 25 CEOs from 2000 to 2010 for the Wall Street Journal. Based on data drawn from company SEC filings that include all compensation, such as stock options, Murphy noted in July 2010 that performance of these lavishly paid CEOs was entirely unrelated to shareholder returns. Pay was utterly random, judged by relative or absolute share price movement. Only five ran firms that outperformed the Dow Jones stock index and four of them ran firms—AC/Interactive, Countrywide, Capital One, and Cendant—whose shareholders lost money during their tenure. And that list doesn’t include infamous losers like Michael Dell, paid $454 million while shareholders lost 66 percent of their value in recent years—much less Richard S. Fuld, who received $457 million driving Lehman Brothers bankrupt in 2008.50 Shareholders in these firms and hundreds, if not thousands, of others burdened with mediocre management endorsed by weak boards would have done better to stick their money under a mattress.

Market Failure in Executive Pay

American executives are overpaid by international standards and far too many are paid without regard to performance, benefiting from market failure in American executive pay. The statistics are persuasive. US compensation levels have been found by academic researchers such as Harvard Business professor Rakesh Khurana to exceed what would be obtainable by executives under the normal conditions of a competitive free market.51 And New York University economist Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef, an economist at the University of Virginia, examined banking industry data over the last century since 1909.52 They concluded that Wall Street pay between the mid-1990s and 2006 ranged from 30 percent to 50 percent higher than if compensation had been determined solely by the normal forces of competition.

Indeed, Professors Edmans and Gabaix found that the 250th best-paid American CEO in 2008 received $9 million—a compensation level only exceeded by a tiny few executives in any other rich democracy.53 It is inconceivable that the most richly compensated 250 American CEOs outperform almost all executives anywhere in the world. Indeed, in light of the weak US productivity and investment performance of the Reagan era, never in history has so much been paid so many for so little. The same market failure exists in the United Kingdom. Pay there, too, is disconnected from performance. A far-ranging study in 2011 by the independent blue-ribbon High Pay Commission “found little evidence that executives’ compensation is correlated with firms’ performance,” as summarized in an editorial by the Financial Times.54

The market failure in executive compensation has dulled American capitalism. Here is Stanford law professor John J. Donohue, president of the American Law and Economics Association:

“It is a terrible mistake to set up a structure where the top person walks away with millions even if the company is laid waste by their poor decision making, yet this is what’s happening. It’s a shocking departure from capitalist incentives if you lavish riches on the losers.”55

How exactly have executives been able to thwart market forces? Certainly, dysfunctional boards are a big factor along with peer benchmarking. But three other factors also appear to be responsible for even the most conscientious and shareholder-friendly boards failing to link pay with performance.56 They are why corporate governance experts Gillespie and Zweig have concluded:

“The bigger problem is the culture of boards, which doesn’t allow directors to do an effective job even if they wanted to.”57

First, Cornell economists Robert H. Frank and Philip Cook found that competition for top business talent has intensified in America in recent decades. Very minor differences in executive performance can have an enormous impact on corporate profits and share prices at large firms. Frank cites the example of a talented CEO heading a multibillion dollar firm whose “handful of better decisions each year” than his competitors can produce hundreds of millions in added profits.58 Shareholders can be convinced to offer excessive compensation in that scenario when bidding for new talent.

Second, the “anti-raiding norms” that discouraged CEO-poaching by competitors during the golden age have “all but completely unraveled,” argue Frank and Cook, producing a winner-take-all competition for top talent akin to Hollywood or the advent of free agency in baseball some years ago.59

Third, stock options became commonplace.

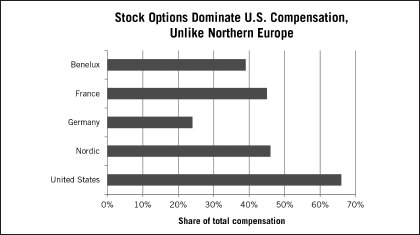

Stock Options

Around for many decades, stock options were rarely utilized by firms until the Reagan era. By the end of that president’s two terms, however, they dominated executive-suite compensation and represent two-thirds of remuneration, as noted in Chart 6.3. The use of options is even higher in instances of gargantuan paychecks: Murphy’s July 2010 Wall Street Journal analysis found that options accounted for 78 percent of the pay of the top 25 bankers he examined.60 The family capitalism countries rely notably less on options.

Chart 6.3. Total compensation is salary, bonuses, and stock options, 2008.

Source: Yann Le Gales, “French Officials Are Paid Less Than Others,” Le Figaro, March 5, 2010.

Stock options were originally envisaged as a solution to the agency problem mentioned earlier, where managers prioritize their own interest, not shareholders’. Adam Smith recognized this disconnect centuries ago, writing critically of enterprise managers:

“Directors … being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they would watch over it with the same anxious vigilance.”61

The weight of evidence is that shareholder capitalism fails to resolve the agency problem, and stock options exacerbate the failure. Indeed, options have been determined to have no persistent impact on shareholder value according to research conducted at the University of Hong Kong School of Business by Liu Zheng and Xianming Zhou. Using statistics from the Computstat® ExecuComp database, they examined the correlation between share prices and 1,337 CEO retirements; these are events when options must be exercised, but whose timing in the preceding years or months is discretionary. The control was the share price of firms headed by retiring CEOs with few option holdings. Zheng and Zhou found that share prices at firms where CEOs held large option positions exhibited abnormal spikes during the retirement period. Unfortunately for shareholders, however, the price spikes were not sustained:

“We find significant abnormal stock returns in the months surrounding CEO departure for those with high option holdings, which are reversed shortly after CEO departure…. Without any persistent effect of stock options on shareholder value, our results do not support the presumed role of options in providing managerial working incentives.”62

Options misalign managerial interests with shareholder interests in two ways. First, management doesn’t necessarily suffer economic loss from poor performance because payouts are nonetheless required under most employment agreements. In 2011, for example, corporate failures like Leo Apotheker (HP), Robert P. Kelly (Bank of New York Mellon), and Carol A. Bartz (Yahoo) received nearly $10 million in severance.63 Moreover, the availability of stock-hedging—where executives can obtain insurance at a minimal cost against losses should the price of their optioned stock fall—further negates individual blowback from negative job performances. New York Times reporter Eric Dash in February 2011 wrote that over 100 Goldman Sachs executives used such hedges to protect against losses during the meltdown and recession, including one whose hedges avoided $7 million in losses.64 Here is how corporate governance expert Patrick McGurn of RiskMetrics explained the conceptual breakdown to Dash:

“Many of these hedging activities can create situations when the executives’ interests run counter to the company. I think a lot of people feel this doesn’t have a place in compensation structure.”65

Second, pay-for-performance is rendered ineffective by the absence of meaningful clawback provisions in executive compensation agreements, and by the inclination of corporate boards to reprice options that go underwater from poor performance. Repricing has occurred in recent years by boards at Starbucks, Google, and Composite Technologies, and frequently reflect abuse of shareholders with management being rewarded regardless of performance. The smoking-gun evidence is provided by professors such as Erik Lie of the University of Iowa and Randall Heron of the University of Indiana. They examined a huge database of nearly 39,000 options granted by 7,700 companies over a ten-year period, finding a pattern of firms listing option grants on dates where share prices are at cyclical lows.66 They discovered, as David Cay Johnston explained: “Executives had an uncanny ability to have options granted to them on the days when the stock price was at its low point during each period. The timing was too perfect to be possible were the rules being followed.”67

Such perfect market timing is extremely unlikely to be random, of course; it reflects backdating, or the equally pernicious insider practice of pricing options on days when adverse corporate performance information is being released to the public. Such practices are apparently legal in most instances.68

Even worse, the prospect of giant rewards from options incentivizes fraud in a US business community already struggling mightily with ethical issues. Drawing on the sociologist Max Weber’s work on the theory of the firm as a collective that reacts rationally to prevailing systems, Nobel Laureate behavioral economist George A. Akerlof and Rachel E. Kranton explained it this way:

“The more a CEO’s compensation is based on stock options, for example, the greater is the incentive to maximize the price at which to cash in. There are at least two ways to do this: one is by increasing the firm’s true value; another is by creatively managing the firm’s books. Recent evidence shows that executives have understood and embraced the second possibility.”69

Yet boards seem unfazed, even routinely writing employment contracts enabling CEOs to receive millions when defrauding their firms. Michael Jensen and coauthor Kevin Murphy have documented the get-out-of-jail cards issued by boards to CEOs who embezzle from their corporations and shareholders. Some 44 percent of all CEO employment contracts they examined required severance payments to CEOs even if convicted and fired for cause.70

One of the most dramatic ways options delink executive reward from shareholder returns in today’s managerial capitalism is by incentivizing risky and economically dubious mergers, which produce suboptimal firm performance. American and foreign research drawing on behavioral economics provides such evidence, portraying stock-optioned American CEOs as jittery children around a candy jar, constantly calculating the prize to the exclusion of shareholder returns or much else. Research by professors Donald C. Hambrick of Penn State University, and William Gerard Sanders of Brigham Young University, for example, caused them to conclude that:

“The more that a CEO is paid in stock options, the more extreme the firm’s subsequent performance, and the greater the likelihood that the extreme performance will be a big loss rather than a big gain.”71

And the biggest losses occur when mergers go bad.

Value-Destroying Mergers Belie Shareholder Capitalism

Milton Friedman insisted in 1953 that a given pattern of managerial behavior will persist only if it is profit maximizing. That is a central dictum of what came to be shareholder capitalism. Yet Friedman’s principle does not align with facts or experience in the real world, as noted by University College London economists Armstrong and Huck. That dictum is belied by the wave of value-destroying mergers characterizing American enterprise in recent decades. Shareholder capitalism incentivizes mergers that destroy shareholder value.

It works this way: managers are rewarded for spiking share values in the current reporting quarter, affording them the opportunity to cash out options. And nothing spikes earnings per share better than a merger that dramatically enhances revenues. But what happens to shareholders, particularly those who have adopted the Wall Street mantra of “buy and hold?”

Economists Ulrike Malmendier, Enrico Moretti, and Florian Peters of the University of California, Berkeley, examined all contested US mergers between 1985 and 2009 where at least two suitors vied. Published in April 2012 by the National Bureau of Economic Research, their analysis examined market evaluations of the successful suitors (acquirors) and losing bidders before and after mergers. Their results were startling:

“After the merger, however, losers significantly outperform winners. Depending on the measure of abnormal performance, the difference amounts to 49–54 percent over the three years following the merger…. We also show that the underperformance of winners does not reflect differences between hostile and friendly acquisitions, variations in acquiror [Tobin] Q, the number of bidders, differences between diversifying and concentrating mergers, variation in targets size or acquiror size, or differences in the method of payment.”72

That is simply an enormous stock price penalty on shareholders of successful suitors. What accounts for the striking underperformance of successful suitors? The culprit was the debt taken on to effect the merger: “Specifically, winners have significantly higher leverage ratios than losers, which the market may view as potentially harmful to the long term health of the company.”

Sharply higher debt as a consequence of mergers was also fingered by University of Richmond economist Jeffrey S. Harrison and Derek K. Oler of Indiana University, who explained the consequences. They examined over 3,000 mergers and determined that enterprise debt leverage concurrently rose an average 45 percent, sufficient to require what economists call risk balancing. That means cutting spending elsewhere in the firm on expenses like R&D and wages; acquirors took on considerable new risk and were forced to pare back other investments and initiatives. Harrison and Oler concluded that management responded “to higher financial risk by reducing risk in other areas, such as new investments.”73

Such as new investments? What? You should have sat up at that, because investment is crucial to productivity growth and to raising incomes. And we will examine the quite serious implications of the Malmendier, Moretti, Peters and Harrison, and Oler’s conclusions in the next chapter.

But to conclude this chapter, let’s see how a more proactively Australia has addressed the issue of rising executive pay.

Australia: Occupy Wall Street Writ Large—with Teeth

By 2010, Australians came to realize that CEO compensation had risen excessively, approaching one-half of American levels. Worse, executive pay had become disassociated from performance. Share prices rose 31 percent on the Australian big board (the S&P/Australian 100 exchange) from 2001 to 2010, but median CEO salaries rose 131 percent and bonuses were up 190 percent. Australian executives reaped four to six times more than shareholders, a broken system just like America.

Voters became aware because the local press began highlighting abusers, such as former CEO Sue Morphet of clothing firm Pacific Brands. The firm lost A$132 million (US$135 million) in 2010 and also the valuable Kmart account; regardless, the directors granted Morphet a bonus of A$910,000 in cash atop her million-dollar salary. BlueScope Steel lost A$1 billion and announced 1,000 layoffs the same day in late 2011 that managing director Paul O’Malley and colleagues shared A$3 million in bonuses.

Over at Commonwealth Bank, a pool of A$36.1 million had been set aside for top executives if specific performance goals like superior customer service ratings vis-à-vis other banks were met. The goals and rules were clear: “In the absence of substantial and sustained improvement [in customer service], no vesting will occur at all,” read the bonus arrangement in 2008 approved by shareholders. The bank fell short, but the board ignored the restrictive language and allowed executive options to vest in 2011 anyway, including A$2.89 million to the CEO Ralph Norris. The same thing happened at giant Downer EDI engineering, and at Boart Longyear, the world’s leading mineral exploration and drilling firm where executives received pay they hadn’t earned. At each of these Big End firms, pay was disconnected from performance.74

And pay abuse was widespread: CGI Glass, an executive pay consultancy that advises investors, pinpointed as lavish the remuneration packets at 52 percent of the 700-plus firms it examined in 2009.75 Australians could have shrugged off this market failure like most Americans do. But Australia has perhaps the globe’s richest tradition of stakeholder capitalism, which includes finely tuned antennae to corporate misbehavior. I have yet to meet a docile Australian—conservative or liberal—when it comes to unwarranted executive pay. Here is how business editor Michael Pascoe of the Sydney Morning Herald described this national intolerance of abusive pay:

“Quantas’s sorry history of overpaying its CEO is as good an example as any on how out of touch Big End boards have become…. The boards genuinely can’t comprehend that they’re responsible for the obscene blowout in executive remuneration, that our society—their employees, their customers, their shareholders—are increasingly jack of it and that their remuneration committees’ excuses simply don’t hold water, let alone multimillion-dollar pay packets…. The defensive attitude of the directors’ club is understandable, though—members don’t want to consider that they’ve been incompetent, that they’ve stuffed up, that the American model of competitive overcompensation is simply wrong.”76

And that explains how David Bradbury came to implement the Occupy Wall Street agenda.

Mr. Bradbury, you see, is the powerful Assistant Treasurer and former Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasurer in Canberra; in November 2010, he echoed public opinion, warning boards that executive compensation was “out of step with community expectations.”77 Pressured by voters, the newly elected Australian Labor government of Julia Gillard responded by adding muscle to shareholder rights’ laws.

Real muscle. Bradbury demanded tighter accountability from corporate boards, because “many institutional investors are taking even greater note of how a company’s reputation is playing out in the wider community and how that contributes to value.” Australians had expectations that local corporations would reform to “lead the world in defining a new brand of corporate leadership.”

And Gillard’s government matched his tough language with an iron fist, enacting the two-strikes pay law in July 2011, which automatically jeopardizes deaf boards ignoring these expectations. If a quarter of shareholders vote against executive pay packages two years running, the board suffers the embarrassment of a mandatory resolution being automatically brought before shareholders to dissolve the board. And if a majority of shareholders then vote for dissolution, the board is spilled; firms have 90 days to conduct elections for a new board.*

With executives and directors accountable to shareholders for compensation decisions, this new law had an immediate impact. In early October 2011, the remuneration package of the first major firm, Sunbeam Appliance GUD Holdings, was rejected; more than one-quarter of shareholders were annoyed that its board had granted CEO Ian Campbell a 33 percent pay hike despite a 14 percent decline in profits. Campbell subsequently told the Sydney Morning Herald, “The board now has no option but to consult with constituents because the shareholders had redrawn the boundaries.”78 The remuneration packages at a number of other firms, including Pacific Brands and Cabcharge, were also rejected by a quarter of shareholders in the following weeks. In total some 108 companies suffered a first strike, a no vote of 25 per cent or more, against their remuneration reports in 2011.79 Australian corporate leaders, as headlined by a local paper, began acting like cats on a hot tin roof. JP Morgan analyst Gerry Sherriff put it this way: “The two-strikes rule puts greater scrutiny on boards to devise executive remuneration structures better aligned with the performance of the company.”†

In most instances, the scrutiny produced the desired moderation, with only a few firms in 2012 like Globe International actually suffering a second strike on remuneration reports, with boards being spilled and new elections required.80

Two strikes is indicative of just how seriously voters in the family capitalism countries take responsibility for their own prosperity. Australian voter expectations regarding the behavior of corporate leadership are demanding. And their goal in this episode was broader than just returning executive pay to earth; it included incentivizing management to adopt longer time horizons and eradicate the American plague of short-termism we discuss shortly. Here is how Sydney Morning Herald journalist Malcolm Maiden describes the three bottom lines of “shareholders, employees, and the community at large” that voters expect corporate boards there to meet:

“A company’s best interests are protected and advanced when the best interests of all stakeholders—including employees, customers, investors, lenders, and suppliers—are taken into account.”81

The two-strikes pay law surely makes American management uneasy. But there’s a lot worse for them ahead. It is time to explore in detail the greatest danger posed by Reaganomics, which is short-termism, and how the family capitalism countries in northern Europe have eradicated that danger. That remedy is also the most frightening nightmare lurking in the sleep of American executives: a black-box corporate governance structure that avoids value-destroying mergers, eliminates short-termism, mitigates CEO narcissism, incentivizes higher investment and productivity growth, and has produced steadily rising real wages across entire economies for decades while creating the most competitive economies on earth.

You are about to learn why America’s best economists, such as Nobel Laureate Edmund S. Phelps of Columbia University, find Reaganomics so maddening—and the real reason why a narcissistic American business community relentlessly demonizes northern Europe.