CHAPTER 12

ECONOMIC MYTHMAKING

“Workers’ leverage is gone. Companies are not creating jobs. Unions that negotiated big wage increases in the 1970s are shadows of their former selves. Cost-of-living adjustments, once commonplace, have disappeared. And the movement of jobs offshore, or the threat of it, has conditioned workers to not even ask for a raise, fearing they will join the millions already laid off.”1

LOUIS UCHITELLE,

New York Times, August 1, 2008

“The conservative response to this trend verges somewhere between the obsolete and the irrelevant. Conservatives need to stop denying reality. The stagnation of the incomes of middle-class Americans is a fact.”2

DAVID FRUM,

speechwriter, President GEORGE W. BUSH August 2008

“Insofar as Americans have any understanding of the alternative policies pursued by other affluent democracies, they mostly seem to reject those alternatives as inconsistent with America’s core cultural values of economic opportunity and self-reliance. European welfare states, they tell themselves, are bloated, ossified and hidebound.”3

LARRY BARTELS,

Vanderbilt University

“No one ever said that you could work hard—harder even than you ever thought possible—and still find yourself sinking ever deeper into poverty.”

Author BARBARA EHRENREICH,

Nickel and Dimed, On (Not) Getting By In America 2001

For most Americans, a profound symbol of the Reagan era is bankers enjoying unwarranted millions of dollars, but at a personal level, the most pervasive symbolism has been income stagnation. Voters attribute this plight mostly to globalization, with remarkably few looking to Washington for remediation. Unaware of the prosperous family capitalism countries, most American families seemingly accept their fate as preordained by inexorable market forces beyond even the power of America.

These low expectations are reinforced by Democratic Party officials, who offer underwhelming tax, trade, and spending prescriptions. Republican Party officials are worse, weakening wages and defending the status quo desired by donors with government gridlock while appealing to voters with combustible social topics. Despite the shambles made of American family economics by Reaganomics, voters see little difference between the parties. Responsibility for this austere—if not to say, discouraging—landscape rests ultimately with pay-to-play politics. But vitally important in nurturing this dismaying environment has been a handful of myths about Reaganomics.

In past centuries, implied or actual military strength maintained a particular arrangement of economic sovereignty benefiting the Roman equestrian class, Chinese dynasties (and their equivalent today), medieval lords, or Renaissance courts.4 The rise of the voting franchise in the nineteenth century altered that dynamic, requiring special pleaders to become imaginative in attracting voters. Thus, robber barons supported creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission to satisfy the farming community’s clamor for lower railroad tariffs, for example, certain in their own ability to exploit pecuniary American politics to achieve regulatory capture; the same pattern has been repeated since. Similarly, economic myth made globalization a bête noire that facilitated the stripping of economic sovereignty from families during the Reagan era. And the canard that deficits don’t matter eased the path to tax cuts. Another myth belied by American economic history is that taxes hamper growth, an important element of the supply-side canard.

The Canard of Supply-Side Economics

Tax cuts for millionaires or the business community are not political positions most voters support. Yet eager to do precisely that, President Reagan relied on message recalibration by Washington. President Reagan’s reputation as a political genius is well earned, especially in reigniting American enthusiasm and confidence. But it was a political tour de force when he and his advisors conjured the canard called supply-side economics. This is the wistful notion that tax cuts pay for themselves by sparking an economic renaissance sufficiently robust to yield new, offsetting tax revenue. No economist believes it occurs, nor does President Nixon’s harshly dismissive Secretary of Commerce, Pete Peterson.

“Federal dollars spent should be paid for out of revenue [but] … the taxing rule was eliminated in the early 1980’s by the jihad prayers of supply-side economists.”5

The notion that tax cuts work this way has been discredited time and again by US economic history; only a John Law would argue that cutting tax rates from, say, 30 percent to 15 percent will spark a sufficient boom to replace the lost tax revenue. Early acolytes brought a religious fervor, making George Gilder’s 1981 Wealth and Poverty a best-seller; media evangelist Pat Robertson argued that supply-side economics “was the first truly divine theory of money creation.”6 President Reagan himself was indifferent about whether this canard was accurate because, as former Republican US Senator Bob Packwood of Oregon explained, Reagan “wanted lower rates and didn’t care how we got there.”7

The lower taxes he and the Bush presidents implemented have not produced an economic renaissance, however, only deep national debt and a nation that consumes too much and invests too little. Even so, Reagan’s intellectual heirs even today still sprinkle supply-side pixie dust to credential tax cuts as the prescription for any and all macroeconomic ailments. And the American business community has been little better, fecklessly urging tax holidays and cuts while exploiting tax havens, which worsen the national debt.

The Myth That Taxes Affect Economic Growth

That pixie dust has been magic for some. Comprehensive US tax rates are the lowest of any rich democracy, ranging between 8 and 15 percentage points of GDP lower than Australia, Germany, and France. Indeed, since American taxes don’t provide comprehensive college or health care benefits, it would be surprising if the US did not have the lowest tax burden. (American corporations also pay about the least as a share of GDP of any rich democracy.)

This low tax burden has come about in part because of tax cuts during the Reagan era, featuring a redistribution of the tax burden onto the middle class, as discussed earlier. Top rates have been lowered and payroll taxes have increased. This redistribution has been sold to voters using the hoary myth that economic growth hinges on the risk-taking and entrepreneurial activities of higher-income households—you know, the job creators. Alan Greenspan argued before Congress in 1997 that the effect of capital gains taxation, “as best I can judge, is to impede entrepreneurial activity and capital formation. The appropriate capital gains tax rate is zero.”8

History teaches that Greenspan was wrong. His assertion is directly contradicted by the postwar American experience. America’s golden age featuring strong growth and job creation occurred when marginal tax rates on higher incomes were about double what they are today. Moreover, the economy performed quite well during the decade 1987–1996, when capital gains rates were nearly twice as high as they are now. Some Republican tax experts, including Bruce Bartlett, acknowledge that tax increases early in the Clinton administration didn’t hinder the robust growth in the years that followed.9 And a Congressional Research Service analysis by economist Thomas Hungerford found that GDP and productivity growth throughout the entire postwar period were unaffected by cuts in income tax rates.10

Taxes may matter a bit to some enterprises, but sales prospects, the economics of relocating abroad, interest rates, and macroeconomic conditions matter far more. That truth is magnified by the ready convenience of tax havens that enable the wealthy and multinationals to avoid taxes regardless of where actual production is located. Turning to individual entrepreneurs, when I’m evaluating whether to pursue a new real estate project, tax rates don’t enter into my calculation at all, and they don’t for most other entrepreneurs either. Not once during the real estate boom years did I accept or reject an investment opportunity because of tax rates. While I’m scarcely in his class, entrepreneurs like Warren Buffett have concluded the same thing:

“It’s not the panacea for economic growth that advocates make it out to be. I have worked with investors for 60 years, and I have yet to see anyone—not even when capital gains rates were 39.6 in 1976–77—shy away from a sensible investment because of the tax rate.”11

A more consequential myth to almost every American family is that wage stagnation is inevitable, a result of global integration and thus beyond the ability of Washington to remediate.

The Myth That Washington Cannot Rectify the Impact of Globalization

Free trade is a wondrous wealth machine, enhancing the allocation of resources and providing higher-quality and cheaper imports, while improving wages abroad and for some employees at home. As consumers and investors, Americans welcomed globalization. But its severe impact on wages has caused many employees to loathe it.

Their ire is misdirected.

The impact of globalization has been extensively studied, as we see in detail in a later chapter. Perhaps the most comprehensive analysis is a 2011 OECD study, which concluded unequivocally that “In contrast, globalization had little impact on the gap between rich and poor.”12

Unlike the United States, experience elsewhere in rich democracies is that globalization didn’t have a significant impact on income disparities. That outcome reflects what has been accomplished by successful public policies in the family capitalism countries to exploit globalization rather than be victimized by it. The dismal effect of globalization in the United States is an exception to those widespread accomplishments. Let me explain.

Global integration has been allowed to become an important wage depressant by Washington officials who acquiesced in its effects redistributing income upward away from families. That is why the impact of globalization on wages, especially high-wage jobs held by non-college folks, has been as severe as the impact on buffalos of soaring global demand for industrial tanned hides in the nineteenth century; they were virtually extinguished in America. And that indulgence is why virtually all men earn less than their fathers or grandfathers before 1980.

Washington officials in thrall to Reaganomics stood aside and permitted wages to erode due to a soaring international labor supply. Here is a truly astounding statistic from a 2007 study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

“There has been a dramatic increase in the size of the effective global labor force over the past two decades, with one measure suggesting it has risen fourfold. This expansion is expected to continue in the coming years.”13

An update based on World Bank data published by Handesblatt in October 2012 concluded than 600 million new workers would be added between 2005 and 2020.14 That will increase the global labor force today of 3 billion by about 20 percent, including perhaps 1.8 billion men and women with dubious or no jobs. Jim Clifton, the chairman of the polling firm Gallup, writes that only 1.2 billion regular jobs now exist.15

The entire American labor force totals 160 million or so men and women. Yet, just since 1990, more new workers than that (187 million) have appeared in China and India.16 And these new entrants work cheaply; in 2008, for example, China Daily reported that Chinese factory workers averaged $3,544 in annual income, or about 11 percent of average US wages.17 That labor overhang opened vast opportunities for executive suites at companies such as Apple to cut labor costs by conducting international wage arbitrage—shifting high-wage US jobs offshore to exploit low wages and docile workforces abroad.

In 2001, economists Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein, and John Schmitt found that some American wages rose during this period, but they documented two factors creating powerful downdrafts linked to globalization:18

First, higher-wage jobs, especially unionized ones, were aggressively offshored, while deindustrialization ensured that virtually all new jobs being created were in low-wage services and at nonunion, lower-wage factories. Economist Michael Spence and Sandile Hlatshwayo concluded that nearly all of the 27 million or so American jobs added since 1990 were in nontradeable service sectors, such as health, where productivity growth is weak.19 And, economist Robert E. Scott at the Washington-based Economic Policy Institute (EPI) has documented that service-sector wages in 2005 averaged 22 percent lower than wages for manufacturing jobs being offshored.20 Worse, even the new jobs being created in the unionized manufacturing sector feature low wages, exemplified by the two-tier wage agreements in autos.21 Some new jobs in tradeable goods sectors at firms like Boeing or on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley pay well, but they are few in number.

Second, the American business community effectively utilized the mere threat of globalization as an intimidator in wage talks. One-quarter of almost 500 corporate executives who responded to a 1992 Wall Street Journal survey, for example, confessed to exploiting the threat of relocating abroad under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as a bargaining tool in wage talks.22 And, Scott’s report for EPI concluded that more than 50 percent of union organizing campaigns in the mid-1990s featured corporate spokesmen threatening to close some or all of the target plants.23

The use of such intimidation tactics doubled in elections monitored by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) after NAFTA was enacted in 1993.24 Cornell economist Kate Bronfenbrenner examined the impact of NAFTA on union-organizing elections in 1998 and 1999. Threats of offshoring notably reduced the organizers’ election success to 38 percent compared to 51 percent in elections where such threats were absent.25

The Reagan era has delivered precisely what many voted against in 1980. No one told American families that they were casting votes to terminate the golden age of stakeholder capitalism. Voters were unhappy with the 1970s stagflation, and likely knew that Ronald Reagan intended to weaken the government safety net; he certainly made no secret of his disdain for it. Americans rejected greater economic security, expecting the trade-off would be a more vibrant and dynamic economy that created a surfeit of good jobs. Grit, education, and effort would pay off, they believed, just as it had in the nineteenth century and the golden age.

American families gambled that Reaganomics would recapture the postwar good times. Instead, Washington abandoned them, admonishing them to respect globalization and the ensuing allocation of income and wealth dictated by the deregulated market. Or at least the market as interpreted by the business community and their Washington men.

Blaming Globalization for the Sins of Reaganomics

Here is conservative author Ross Douthat writing in February 2012, shifting responsibility for the outcome of Reaganomics onto globalization:

“It was globalization, not Republicans, that killed the private-sector union and reduced the returns to blue-collar work.”26

Too many economists were taken in by this canard delivered with certitude by folks like a writer for the Economist in June 2006:

“The integration of China’s low-skilled millions and the increased offshoring of services to India and other countries has expanded the global supply of workers. This has reduced the relative price of labour and raised the returns to capital. That reinforces the income concentration at the top, since most stocks and shares are held by richer people. More importantly, globalisation may further fracture the traditional link between skills and wages.”27

And it was delivered with gravitas by folks such as the economist Michael Jensen of Harvard whom we met earlier. Here it is boiled down by Jensen and Perry Fagan in the Wall Street Journal in March 1996:

“The political dynamics behind this third industrial revolution is the spread of capitalism in response to the worldwide failure of communism…. This move to market-oriented, open economic systems is putting 1.2 billion Third World workers into world product and labor markets over the next generation. Over a billion of these workers currently earn less than $3 a day…. The upshot of all this for Western workers is that their real wages are likely to continue their sluggish growth and some will fall dramatically over the coming two or three decades, perhaps as much as 50 percent in some sectors. Wages will, however, reach a trough and recover as the cycle works its way through the system.”28

With Chinese textile workers earning 86 cents an hour and Cambodians 22 cents, this chilling prospect, credentialed by Harvard professors, the Wall Street Journal, and the Economist was enough to make one seriously question the utility of an economic system that so severely penalizes Americans. After all, the United States had won the Cold War and all the rest, yet most citizens were seemingly destined to be treated like its losers while others grew rich. That made Jensen and other experts important apologists who could credential Reaganomics—busily explaining away how capitalism isn’t broken, despite this grim prospect. We know that because of the title of Jensen’s editorial:

“Capitalism Isn’t Broken”

Jensen was wrong, at least, about the variant pursued in America during the Reagan era. American capitalism transformed into Reaganomics is broken. But that’s only the beginning of the story.

The studied indifference by officials in Reagan-era Washington to off-shoring and, more generally, to the wage impact of global integration, stands in sharp contrast to the results achieved by alternative policies in the family capitalism countries. In those countries, real wages continued rising, evidence that the economic loss and diminished living standards rationalized by Jensen and others were not preordained. Deindustrialization, the loss of good jobs to offshoring, and wage compression are not ineluctable. Americans didn’t have to become the losers that Europeans such as Handelsblatt chief editor Gabor Steingart acknowledge, or those described in that newspaper by Norbert Häring, coauthor of the 2009 book Economics 2.0:

“Many millions of Americans lack adequate health insurance and cannot afford medical care. The average life expectancy is significantly lower than in most other industrialized countries. In a comparative study by UNICEF of the quality of life of children in 21 industrialized counties, the US safety and health of children landed in last place, far behind much poorer countries like Greece, Hungary, and the Czech Republic…. A larger proportion of the population lives in absolute poverty than in many European countries and Canada.”29

That grim rendition is not the consequence of capitalism, but of Reaganomics—and of American officials, economists, and voters who believed the myth that rich democracies are helpless before globalization.

Another myth is that policies to fend off the impact of globalization inevitably reduce economic efficiency.

The Myth That Promoting Income Equality Reduces Economic Efficiency

Iconic Yale economist Arthur Okun penned a book in 1975 entitled Equality and Efficiency: The Big Trade-off. The implication is that economic growth inevitably produces income disparities, and policies to ameliorate this side effect imperil economic growth. And a majority of Americans have come to accept that even the widening income disparity of today is an inevitable, if lamentable, price to pay for economic growth. In December 2011, for example, 52 percent of respondents to a Gallup poll viewed income disparities “an acceptable part” of attaining growth.30

They’re wrong.

While true at times, the Reagan era has proven that trade-off to be mythical. Preventing income disparities doesn’t inevitably impose an economic efficiency penalty. The family capitalism countries broadcast rising incomes widely across society even while nearly all attained better productivity performance than Reagan era America, and much stronger real wage growth as well. These decades of evidence from a host of rich nations reveal that any efficiency/equality penalty can be neutralized in the real world.

Indeed, economists Andrew Berg and Jonathan Ostry with the IMF have concluded that nations with less income disparity experience faster growth. Analyzing data from 1950 to 2006, they discovered that income equality is as important to growth as is openness to free trade. Nations with high-income equality experienced higher average rates of economic growth by avoiding disruptions such as credit crises that are precipitated when economic elites achieve financial deregulation.31

In family capitalism countries, gains from trade and economic growth are widely distributed. They met the challenges of globalization and technology change by opening borders to garner the enormous wealth from the improvement in resource allocations and efficiency. At the same time, they upskilled workforces and adopted institutions to ensure the gains would be broadcasted widely, not monopolized as in the United States. Income gains from globalization nurtured most families, rather than just tiny business elites along Berlin’s elegant Kurfurstendamm, in the stylish sixteenth arrondissement of Paris, or in Sydney’s beautiful Point Piper suburb. Their success reaffirms faith in capitalism and provides hope and a powerful model for America.

Another myth sustaining Reaganomics is that income stagnation for Americans can be avoided with education and upskilling.

The Myth That Education and Upskilling Can Solve Wage Stagnation

Many economists and commentators blame faltering American education as partly if not largely responsible for widening income disparities. The columnist David Brooks, for example, suggests that wage stagnation can be resolved by returning to America’s education roots: “What’s needed is not a populist revolt, which would make everything worse, but a second generation of human capital policies, designed for people as they actually are, to help them get the intangible skills the economy rewards.”32

Brooks is precisely incorrect on the solution, but his point has merit. It is certainly accurate that global integration accelerates the usual creative destruction process of innovation and entrepreneurism described by Josef Schumpeter that rewards the educated. Their rising wages are price signals for employees to upskill and raise educational attainment. Bolstering the skill set of Americans with improved education and upskilling is a constructive, though not sufficient, resolution to wage stagnation. Educational attainment pays off at the individual level, as every parent knows. Among economists, this line of argument is driven by Nobel Laureate Gary Becker and others, who have convincingly shown that education yields benefits at the individual level; the more you learn, the more you earn. And episodes of joblessness are shorter, too.

America led the world a century ago in providing broadly based public education that became one foundation of the golden age. As Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz have noted in a careful, data-rich book, those receiving educations in the European nations at the turn of the twentieth century tended to be those who could personally afford schooling.33 America rejected this elitism and greatly expanded its education base. The ensuing rise in human capital stock powered productivity growth, enabling America to become the richest nation in the world. Later, in the decades after World War II, rising productivity and wages linked to rising education attainment created the great American middle class.

Those verities still apply. Yet the notion of education as a panacea is deficient, because it ignores the structural problems reflected in the delinking of productivity and wages by Reaganomics. It would be a delight to learn that education was the solution to the middle-class ills of today, a much easier target politically to tackle than the national epiphany required in voting booths and in composition of the Supreme Court.

The structural nature of wage stagnation and why more education and upskilling in the Reagan era has not translated to better wages have been examined by a host of economists.34 Here is how economists Ian Dew-Becker and Robert J. Gordon explained it in 2005:

“Most of the shift in the income distribution has been from the bottom 90 percent to the top 5 percent. This is much too narrow a group to be consistent with a widespread benefit from SBTC [skill-biased technical change]….”35

Educational attainment now in the family capitalism countries is not much different than in America, but wages are higher and continue rising. What is different are wage and labor market policies and national expectations about the behavior of corporate boards of directors.

If education paid off, surely those Americans with college educations would be at least out-earning college graduates forty years ago. Yet they are not. Economists have determined that college graduates have been among that 90 percent of Americans whose wages failed to even keep pace with inflation over the last 35 years: Heidi Shierholz at EPI has documented that inflation-adjusted starting wages for graduates in 2010 for both males ($21.77 per hour) and females ($18.43) were about 5 percent lower than in 2000 ($22.75 and $19.38).36 It’s the same story over a longer period for all male college graduates as documented by Adam Looney and Michael Greenstone of the Hamilton Project. Annual median earnings for male employees with college degrees in 2009 were 7 percent lower than in 1969 during the peak wage years.37

The only clear beneficiaries of rising wages among the college educated have been those relatively few with advanced or professional degrees, but even their gains have been mediocre. Indeed, wage stagnation is commonplace even in those professions most tightly linked to the information technology (IT) revolution. The 2005 study by Dew-Becker and Gordon included a detailed examination of the period 1989–1997, an era marked by the IT revolution and heightened demand for math and computer skills. They found that despite strong demand for computational-skill labor, real wages “in occupations related to math and computer science increased only 4.8 percent and engineers decreased 1.4 percent.” Yet, “… total real compensation to CEOs increased 100 percent.”38 It is extremely difficult to see how a surge in American education attainment will reverse a pattern where CEO salaries double, while the wages of skilled computer engineers barely outpace inflation.

Some conservatives acknowledge this inconsistency, including N. Gregory Mankiw. He has noted that while education is “not irrelevant,” one’s educational attainment doesn’t explain how a relative handful of Americans have prospered while the wages of all others stagnated since the 1970s: “It is less obvious whether it can explain the incomes of the super-rich. Simply going to college and graduate school is hardly enough to join the top echelons.”39

Education as the cause or answer to wage stagnation is a myth of Reaganomics. Three smoking guns document its status as a canard: First, the share of Americans with college educations has risen from 19.7 percent in 1979 to 34.4 percent now, yet real average and median wages have stagnated or fallen.40 Second, a significantly greater proportion of Americans than Germans (34.4 percent versus < 25 percent) have college degrees, yet wages are significantly higher there.41 Third, compensation for most Americans does not rise with productivity, which is the best measure of their skill and education (and value to employers), as judged by labor markets.

With globalization and faltering education ruled out as sources of wage stagnation, what are the factors responsible?

Why Wages Stagnate

The elements of Reaganomics are major factors in wage stagnation, including its Randian corporate culture, offshoring, short-termism, and quarterly shareholder or managerial capitalism. Another factor has been the failure of Washington officials to mimic the tactics of the family capitalism countries in ameliorating the impact of globalization. Economists cite three other significant factors: employer collusion to limit wage increases, the sagging minimum wage, and the weakening of employee collective bargaining power.42

Employer Collusion to Minimize Wages

Even blue-chip enterprises cross the line in colluding to suppress wages. For example, the Obama administration’s Department of Justice settled two antitrust lawsuits in 2010, in which several leading high-tech firms agreed to pay penalties for conspiring against their own highly skilled artisans. Lucasfilm and rival Pixar were found to have illegally colluded to avoid wage-bidding wars for prized digital animators. Adobe Systems, Apple, Google, Intel, and Intuit were similarly caught for colluding to dampen the wages paid to top technical talent.43

Kneecapping the Minimum Wage

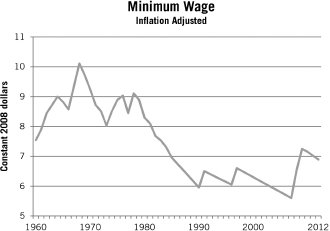

As a student in 1968, I earned the minimum wage stocking grocery shelves, which was comparable to $10.11 measured in 2008 dollars. And it was still high, around $9/hour in today’s currency, when amiable President Reagan was elected. That substantial level for the minimum wage provided a solid economic floor beneath American incomes during the golden age. It also proved to be a muscular antipoverty mechanism, setting a living wage floor sufficient to prevent abject family poverty.

The logic of the minimum wage is straightforward: without a robust market for labor or a wage floor beneath them, history since the industrial revolution teaches that market forces produce a race to the bottom for wages. The American experience during my first years of work demonstrated how successful minimum wages can be. During its peak years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, America enjoyed the lowest poverty rates ever in its history (11.1 percent in 1973) and higher real wages than today. And the lowest recorded rate of childhood impoverishment ever in America was in 1969, at 13.8 percent.44 Most persuasive is that year after year in this period, America recorded among the lowest unemployment levels in postwar history despite the high minimum wage.

But that was before the Reagan era. A prominent target of the business community, the minimum wage became a quick victim after 1980, despite its centrality to the prosperity of America’s lower-income employees. As depicted in Chart 12.1, it began a steady slide eroded by inflation, falling a third over the following decades, before being raised modestly during the Clinton administration and again in 2007 at the insistence of Congressional Democrats. This erosion has had a generalized impact because minimum wages serve as an escalator, pushing up wages for workers further up the income scale. The US experience sharply contrasts with policies in the family capitalism countries, where minimums are considerably higher, as we will learn in a later chapter. The minimum wage, for example, in France during 2012 was €9.22 per hour; in purchase-power parity terms that is over $11 per hour, or 60 percent above the federal minimum in America. The minimum wage in Australia is higher still.

Chart 12.1.

Source: Wage and Hour Division, “History of Changes to the Minimum Wage Law,” Department of Labor, Washington, DC. Also: Phyllis Korkki “Keeping an Eye on the Low, Point of the Pay Scale,” New York Times, August 31, 2008, and Ralph E. Smith and Bruce Vavrichek, “The Minimum Wage: Its Relation to Incomes and Poverty,” Monthly Labor Review, June 1987.

Another important explanation for the wage stagnation of recent decades was regulatory capture, particularly of federal labor market regulators who turned hostile to unions promoting higher wages.

Diminishing the Golden Age Role of Unions

You may recall that the organization Human Rights Watch criticized European firms in September 2010 for exploiting weak American labor rights. HRW concluded the firms were, “adopting practices common in America but banned in Europe,” by seeking “… to create a culture of fear about organizing in America.”45

The business community has targeted trade unions in its pursuit of the gains from growth because they raise wages and because they support opponents of Reaganomics. Research by economists Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld determined, for example, that union membership confers a lifelong wage premium on blue-collar employees comparable to that of a college education. “The decline of the US labor movement has added as much to men’s wage inequality as has the relative increase in pay for college graduates,” they concluded.46 Moreover, the existence of trade unions is a precursor to a high-wage economy as in Australia or Germany, because they elevate the wages of nonmembers as well. Economist Henry Farber, for example, has concluded that wages of nonunion employees are 7.5 percent higher if at least 25 percent of a particular industry’s jobs are unionized.47 Their presence strengthens family economic sovereignty.

Their importance to family prosperity also accounts for the centrality of unions in historic Catholic social teachings for well over a century. Leaders including Pope Leo XIII taught that a strong trade union movement is “greatly to be desired.” In his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, Pope Leo explained that unions “have always been encouraged and supported by the Church.” And that support has remained steadfast in the modern era, as indicated by this 1986 pastoral letter from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops:

“No one may deny the right to organize without attacking human dignity itself.”48

The success of wage compression tactics targeting unions in the Reagan era is indicated not only by wage stagnation, but also by the union share of the private sector workforce, which has dwindled to below 7 percent from 35 percent in the 1950s; including the public sector, that share has dropped to about 11 percent. A major reason has been the barriers erected during the Reagan era to union organizing.

A comparison with Canadian law and practice is instructive. While the share of employees interested in joining unions is similar to the US, membership is nearly three times higher in Canada because labor organizers face fewer roadblocks. Indeed, the Canadian membership rate is close to the US rate during the golden age, when organizing rights were better enforced.49 As Kris Warner with the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research noted, a Canadian union is generally recognized once a majority of employees indicate intent to join over employer objections. Unlike US employers, Canadian employers do not have a second opportunity (involving an election and lengthy delays) to derail organizers using American-style tactics.50

Labor rights set forth in the National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act were weakly policed during the Reagan era. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), traditionally composed of prominent scholars, attorneys, and career civil servants, became toothless, increasingly filled with lobbyists and other ideologues.

Cornell professor Kate Bronfenbrenner examined more than 1,000 union election campaigns over a recent five-year span. Most featured employers conducting Madison Avenue-style campaigns targeting employees, with 57 percent threatening to export jobs, and even entire plants, if unionization occurred. And 34 percent of the campaigns included the illegal firing of union advocates.51 Here is the outcome, as described by labor attorney Thomas Geoghegan.

“Employers found out they could just ignore the Wagner Act and fire pro-union workers right before so-called ‘secret-ballot’ elections; they found out there was no real limit on what they could use as a threat.”52

These public relations campaigns were conducted in conjunction with niche law firms specializing in union busting. Lawyers taught executive suites where enforcement was weak, how to bend the rules, and how to greatly muddy the simplicity of union-organizing elections. New York Times journalist David Leonhardt explained: “Companies pay minimal penalties for illegally trying to bar unions and have become expert at doing so, legally and otherwise.”53 The ultimate goal was to slow-walk the union election process, in order to buy time for executive suites to ferret out and fire union sympathizers.

Fired union advocates frequently complained, but pleas fell on deaf ears at a US Department of Labor behaving like the Interstate Commerce Commission in the nineteenth century. It was more interested in protecting employers from employees than achieving the balance prescribed by the Wagner Act. Even when legal steps by aggrieved employees forced NLRB action, official foot-dragging was common, with Labor Department administrative-law judges taking an average of eighteen months to rule on a complaint of unfair labor practices.54 Here is how the Washington Post in an editorial summarized these tactics:

“From the point of hiring, employers have unfettered access to workers to make the case against forming a union. When unions launch organizing campaigns, employers can require workers to attend repeated antiunion presentations, while unions have no comparable access to workers and are left to try to contact them off company premises. Although it is illegal for employers to fire or threaten workers for joining a union, enforcement is inadequate, with penalties too late and too small to deter violations.”55

The NLRB during the G.W. Bush administration permitted employers to place new hurdles in the path of unions, even those managing to win organizing elections. Researchers John-Paul Ferguson and Thomas Kochan of the MIT Sloan School of Management examined the outcome of organizing campaigns from 1999 to 2004. In cases where employees prevailed—winning a majority vote to organize—they were subsequently able to negotiate a contract only 56 percent of the time.56 Why? There were at least three reasons:

First, many employers who lost organizing elections simply refused to negotiate a union contract. If they stonewalled election outcomes for one year, Bush administration regulators generally allowed them a second bite at the apple: employers could request that the union victory a year earlier be decertified, forcing the entire time-consuming and expensive electoral process to be repeated.57 Victories thus delayed became victories denied.

Second, as exemplified by the tactics of Walmart, executive suites routinely flouted the intent of laws by simply shuttering facilities, such as a meat department where the majority of employees had voted to organize. Punishment for such illegalities, consisting of employee reinstatement and back pay, was de minimus, too small to deter large corporations.

Third, nearly forty years ago, employers discovered that Chapter 11 of the bankruptcy code was a useful tool in avoiding or breaking labor contracts. Business units that voted to unionize were suddenly discovered to be money-losers, declared bankrupt by employers and temporarily closed—only to reopen later with a newly hired, chastened workforce. Worse, faux Chapter 11 bankruptcy became a tactic to break existing labor agreements, particularly those that required high wages or benefits be paid for many years in the future. Here is how labor attorney Geoghegan explained this scam:

“Right around the time Reagan took office, companies began to figure out that they could go in and out of Chapter 11 in order to dump their obligations, not just to workers but also to retirees. Often the companies weren’t ‘bankrupt.’ The parent firm was simply shutting down the subsidiary…. With a competent lawyer, any employer can cancel any promises to any worker.”58

The Chapter 11 ploy was utilized to obviate or sharply pare back retiree pensions or health-care obligations to only pennies on the dollar. In bankruptcy, employees “managed to hang on to five cents on the dollar, maybe ten” cents of prior obligations promised by employers, concluded Geoghegan.

Taking the totality of these various union-busting strategies into account, Bronfenbrenner concluded that the balance between labor and management that had empowered the golden age has been knocked askew since.

[Employers take] “… full advantage of current labor law to try to keep workers from exercising their full rights to organize and collectively bargain under the National Labor Relations Act. Far from an aberration, such behavior by US companies during union-organizing campaigns has become routine, and our nations’ labor laws neither protect workers’ rights nor provide disincentives for employers to stop disregarding those rights.”59

The final myth examined in this chapter is that stakeholder capitalism underperforms.

The Myth That European Economies Are Sclerotic

The most authentic European version of Milton Friedman was the late German economist Herbert Giersch. He emulated Friedman in fierce antigovernment rhetoric and writings, and also in conducting a public relations effort to discredit stakeholder capitalism under the auspices of the Kiel-based Institute for World Economics. During the 1980s, for example, Giersch coined the catchy term “Euro-sclerosis.”60 It has been mimicked since by some American conservatives to denigrate European economies as ossified, with stultified labor markets and firms cowering behind protectionist tariff walls.

Henry Olson of the American Enterprise Institute, writing in the Wall Street Journal during 2008, miscast Europe this way: “Germany, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands are poorer than the United States, with substantially higher unemployment rates and slower economic growth.”61 France is regularly demonized, including a 2007 editorial in the Washington Post arguing it needs “weaning … from a mind-set that disdains and devalues work.”62 And here is reporter Simon Heffer of London’s Daily Telegraph, cheerleader for the conservative Tory party and critic of continental Europe: “While much of the rest of the World moves on through the application of free-market disciplines, France is demoralized, impoverished, overtaxed, and in despair.”63

A similar verdict was issued in 2001 by law professors Henry Hansmann and Reinier Kraakman, who described stakeholder capitalism and codetermination as “a failed social model.”64 Disciples of Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand, their article was entitled “The End of History for Corporate Law.” Their writing was reminiscent of political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s inaccurate commentary on the end of the Cold War or Oswald Spengler’s much earlier prediction amid the carnage of World War I, in his chilling The Decline of the West, that Western civilization had begun an inevitable downturn.

Even the Economist magazine promotes the canard of a sickly Europe, as it did in June 2006 with unfortunate timing, not long before the US housing bubble burst. Editors fretted that income and wage stagnation in America may embolden European resistance to the spread of Reaganomics, thereby “setting back the course of European reform even further.” Later, amid the 2007/2008 credit crises, editors there persisted in praising Reaganomics:

“This is a black week. Those of us who have supported financial capitalism are open to the charge that the system we championed has merely enabled a few spivs [petty thieves] to get rich. But it helped produce healthy economic growth and low inflation for a generation.”65

Well, the part about spivs is spot on, but the balance of the editorial is mendacious. One is hard-pressed to term what has happened to American families and their household wealth as “healthy economic growth.” And the economic outcomes were even more sickly in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain, which had foolishly mimicked Reaganomics.

Even so, the expansive Reagan era demonization of European stakeholder capitalism was successful in forming public opinion, as noted by Princeton political scientist Andrew Moravcsik. He was quoted in the New York Times in October 2008, saying that “Americans, especially conservatives, have a particular view of Europe as over-regulated, therefore suffering from weak growth and Euro-sclerosis.”66 Political scientist Bartels wrote similarly in an epigraph to this chapter, and here is Mark Leonard at the Center for European Reform:

“Many Americans see the European economy as the business equivalent of a hippy commune—mired in the 1970s, unable to reform because of the cacophony of voices that erupt every time a decision needs to be made, and more interested in soft-headed ideas of quality of life than economic performance. They argue that it will not succeed until it emulates the United States with lower taxes, less social protection, a smaller state, and a narrow focus on shareholder value.”67

As we are learning, reality is much different.

Northern Europe Is an Economic Powerhouse

A number of European firms such as Ikea and Siemens are among the most profitable multinationals in the world. Some European internet startups such as Angry Birds have become part of America’s social fabric. BMW, Daimler, and VW-Porsche-Audi perennially compete to claim the title of the world’s best-managed auto firm in what has become an intramural German competition. The widespread prowess of firms across northern Europe results from their deep integration with globalization and codetermination. Europe is not an easy market for US firms, because its openness to trade also has made it the richest and the most fiercely competitive market in the world. And it is the world’s largest market, easily exceeding American share of global output. In the 2000s, some 61 of the world’s 140 largest firms on the Global Fortune 500 were European, compared to only 50 from the United States and 29 from Asia.68

Some might think that its high wages exist only because of trade barriers or inflexible labor market rules shielding uncompetitive firms. Reality is starkly different: superior corporate governance, high investment, and robust productivity growth enable northern European firms to pay high wages while out-investing and out-exporting America’s finest. Globalization means Schumpeter’s creative destruction process occurs at a faster pace than in America. Since 2000, for example, some 5 million Germans in 340,000 firms have lost their jobs from bankruptcy, reports Neuss-based Economic Reform Credit.69 And wages can and do decline, even in France. Employees at the Bosch facility in Beauvais agreed to wage and benefit cuts in 2004, as did employees at Hewlett-Packard in 2005, at Continental Clairoix in 2007, at Peugeot Motorcycles in 2008, and at GM’s Strasbourg gearbox plant in 2010. Sometimes lower labor costs preserve jobs, but sometimes not: the Bosch and Clairoix plants subsequently closed.70

Americans have fretted about the rising economic prowess of China since their exports surpassed US exports in 2007. Few realize that stealthy northern Europe is the real global export colossus. Despite the American advantages in commodity exports such as food and coal, exports from Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands grew faster from 1999 to 2009.71 No democracy except Australia has benefited more from globalization. Here is the European specialist economist Barry Eichengreen:

“European exporters continue to dominate international markets in precision manufactures ranging from luxury sedans to dialysis machines. It is the United States, not Europe, whose auto companies and airlines are on the ropes owing to low productivity and poor product quality and which have massive trade and current account deficits…. [And] … the stronger hand of government in setting product standards has given European firms producing high-tech products a leg up on their American competitors. After all, for much of the 1990s, it was not some US high-tech giant but Nokia, from tiny Finland, that dominated the global cell phone market. The point is general: European firms continue to compete successfully in a wide range of high-tech products, from pharmaceuticals to high-speed trains.”72

And Germany is the greatest beneficiary of all; codetermination. makes that country easily the globe’s most competitive economy measured by exports per capita, where the long term is measured in years rather than in months. For even the canniest American CEO to step into the executive suite or boardroom of a German firm such as VW would be like stepping onto the bridge of the starship Enterprise. Expectations of competence, vision, and expertise would be higher. Every decision would be ruthlessly parsed by expert colleagues wielding a great deal of detail and their own competing robust visions for the firm. And he or she would be paid a great deal less as CEO in the bargain. American CEOs would hate it.

Led by France and Germany, northern Europe is reformulating the EU, with a final amalgam still to be determined as the region’s sovereign debt crisis plays out. The current challenges should not obscure the fundamental strength found in the superior corporate governance and resulting superior economic performance of these family capitalism economies. And the key is their openness to globalization, making them investment magnets. Nearly one-half of the funds invested in the French stock market (the CAC 40) come from abroad.73 And, between 2000 and 2005, the EU received nearly one-half of global foreign direct investment, far more than China and the United States combined.74 Yet, northern Europe’s cutthroat competitive environment is not for every American corporation, as we will see in a moment.

Competition is fierce. We learn that from the behavior there of the iconic American firm McDonald’s. Its outlets in northern Europe deploy more upscale décor and menus than in America. Tough competition has left it little choice but to grant local management almost carte blanche to innovate. Instead of competing by hiring Washington men to harp about taxes and regulation, the company reinvented its railway station café image with innovations first introduced there: table service, automated order kiosks, and café settings with upholstered or Danish-style egg chairs that compete directly with local coffee shops.75

McDonald’s is not an isolated example. Most Americans pay little attention to northern Europe. But that isn’t true for a key cohort of influential, wealthy, and important Americans who run the largest and most competitive US multinationals. These keen observers have led a wholesale flight of American firms to northern Europe in recent decades. Thousands of America’s most competitive and vibrant enterprises have invested there, including 3,000 in France alone,76 creating more than 500,000 jobs, with more than $1 billion a week in commerce flowing between that country and the United States.77 In Germany, the 4,000-strong US Chamber of Commerce claims that US firms account “for approximately 800,000 direct jobs and over $100 billion in investment.”78 Pete Sweeney with European Voice acknowledges that European affiliates of American companies in total employ millions of Europeans,79 including more than 100,000 Ford and GM auto workers alone.80 Even amid the current debt crisis and slowdown, firms like Amazon continued adding thousands of jobs across Europe during 2012 and 2013.81

And, not a single one is a crummy US-style job.

Their investments evidence the normal greed motivating capitalism. But they also highlight the disingenuous attitude of American executives toward stakeholder capitalism. Back home, US multinationals lobby against higher wages, preventing their American employees from living as well as their European employees.

The word you’re searching for is duplicity.

American Business Keeps You in the Dark While Creating Jobs and Paying Higher Wages in Europe

I first noticed the phenomenon in 2004. Rental cars in Europe began to baffle me, with power-window rocker switches you had to pull up instead of down. Really odd, because new cars back home still came with the old switches. The explanation was a new EU regulation—one which American firms successfully fought at home. It turns out that toddlers can accidentally push down window rocker switches with tiny toes, and some were strangling as a result, including seven American youngsters in just three months in 2004. Worried about profits, Detroit killed remedial regulation—the safer pull switch—but Europe puts families ahead of profits. It wasn’t until 2006 that the death toll grew sufficiently large to convince the Bush administration to do what parents and safety advocates had been demanding for years.82

Rules have consequences, and rules like this embodying family capitalism in Australia and northern Europe annoy American firms. What CEO likes being told what to do, especially by employees and moms? Yet, as business professor Rakesh Khurana argues, “If there’s an ideology of management, it is pragmatism.”83

American firms abroad comply with local customs wherever on the globe they do business. That sometimes produces behavior their American shareholders and employees would find startling—none more surprising than their behavior in northern Europe. There, they pay close attention to the concerns of all stakeholders, including employees, customers, and debt holders, and follow the rules of family capitalism, because they have to.

That means all US firms operating in northern Europe negotiate openly and in good faith with trade unions and government agencies about annual wage increases. They agree to split productivity gains with their employees each year, pay wages above what they pay in America for the identical work, grant year-end bonuses and the conventional four to six weeks of vacation. And, they interact routinely with employee work councils. Moreover, firms like Ford eagerly use European government programs to limit layoffs and retain skilled workforces, a decidedly un-American practice.84 And they pay many billions of Euros into government health care, pension, worker training, and other programs supporting family capitalism.

Multinationals do it for the profit with eyes wide open. Their attitude is exemplified by TIAA-CREF, the American global pension and investment manager. Like most other American multinationals these days, it can be found in every nook and cranny of Europe. They know firsthand that family capitalism works and acknowledge that Reagan-era America “is not necessarily the best model for everyone. I think there is a great awareness that other models make sense. There is no one-size-fits-all for companies,” according to John Wilcox, former head of corporate governance in 2010.85

The reality is that American firms readily comply with the customs in stakeholder capitalism of work councils, codetermination, splitting annual productivity gains with employees, and union bargaining agreements.

They will do the same thing in America when voters change the rules to prioritize family, rather than firm, prosperity.

America’s Low-Wage Model Fails in Europe: Walmart

Institutionalizing stakeholder capitalism rules in the United States would require firms to adopt the model used by American multinationals in Europe. It may not be a happy experience for some. Consumers in family capitalism countries have high expectations that firms will support, rather than exploit, customers and employees. That makes them poor fits for enterprises reliant on the disposable labor model.

Forced to pay double their accustomed American wages, US firms in northern Europe must draw deeply from innate management expertise to adapt. Many like Amazon, McDonald’s, and Starbucks have displayed the superior management skills needed to survive, paying high European wages while providing quality service and products. There are similar success stories in Australia. Domino’s Pizza, for example, has prospered in Australia and New Zealand despite what CEO Don Meij describes as their “Scandinavian labor costs. The labour cost of a US delivery driver is one-third the price in Australia.”86 Despite paying high wages, Domino’s exploited the internet to raise profits by 15 percent in 2011 in Oceania. But other US firms with weaker management have foundered badly under stakeholder capitalism.

The most instructive example is Walmart; the company’s experience offers multiple lessons. The adventure began when Walmart purchased the Wertkauf retail chain in 1997 and the 74-store Spar Handels chain in 1998. The result was 85 German Walmart stores, with 11,000 employees and excellent economies of scale. But it was downhill from there.

Walmart is among the world’s largest firms, but management was overmatched when confronted mano a mano with rules and expectations about corporate behavior in Germany, and with seasoned German retailing giant Metro. Self-inflicted damage by Walmart executives seeking to apply its American business model rapidly doomed the expansion. One challenge was that the lush German retail sector places a premium on customer relations, while Walmart’s strong suit is low prices based on low employee wages and inexpensive Asian imports. Moreover, what could charitably be termed its quirky corporate culture alienated far too many potential customers. For example, it quickly garnered unhelpful publicity for poor employee relations, treating German workers like its American workforce: as problems rather than partners. Management-labor relations supporting high wages are vital to family prosperity, which means that European shoppers are generally unwilling to support “bad citizens” who chisel employees by legalistically manipulating rules to find loopholes. Forced to adhere to demanding consumer expectations about firm behavior—and eventually forced to pay nearly double its American wage structure—Walmart had difficulty viewing its expensive employees as assets useful in improving its corporate image and interpreting local consumer inclinations.

From the start, poor labor relations were a problem, as controversy with its employees erupted into public squabbling. Walmart stalled wage negotiations and demonized its employees’ unions. It also slow-walked implementing traditional northern Europe nonwage workplace practices that management found inconsistent with the hierarchical American mode. Work councils, for example, are useful early warning tripwires for European firms eager to draw on experienced employees. Indeed, veteran local hires were potentially of great value to a neophyte like Walmart. But Walmart instead simply wanted trade unions, work councils, and high wages to disappear—as in America.

Walmart’s management adopted practices that repeatedly resulted in public ridicule. One consequence of failing to consult with employees was the unfortunate instigation of an anonymous informer hotline, apparently common in its American stores. German employees were encouraged to secretly inform on one another, in an astounding display of insensitivity in light of Germany’s recent history. This episode was in a class by itself for amateurish management and proved far too redolent of Germany’s Communist and Nazi past for customers. Even so, Walmart ended the policy only when a German court declared it illegal. The informer hotline episode was then magnified by widespread publicity in Germany surrounding Walmart’s decision at around the same time to close its Jonquière store in Quebec, Canada; the firm eliminated hundreds of Canadian jobs rather than accept a collective bargaining agreement.

As curious Germans digested these events, they voted with their feet, staying away by the millions.* Burdened with a tarnished image, Walmart confronted a choice after just a few years: adapt or abandon Europe. Other firms in similar straits—the grocery convenience retailer Lidl, for example, which had a similarly unsavory reputation for spying on employees—had succeeded in adapting to community expectations.87

But reform seemingly is not Walmart’s strong suit. And so it bolted, abandoning its European operations in 2006 in favor of expansion in Asia, Latin America, and India, where local rules are more accommodating to its low-wage and disposable labor practices. Walmart sold its operations to competitor Metro after losing nearly $5 billion, according to the leading German retail industry weekly magazine Lebensmittelzeitung. Hans-Joachim Körber, CEO of competitor Metro, was reported to have said he “cannot hide his satisfaction … that the US retail giant lost out and paid dearly for it.”†

McDonald’s in Europe

Walmart’s flight stands in contrast to the experience of other American firms in northern Europe, even those such as McDonald’s that rely on the same low-wage model. McDonald’s established its first store in Europe over thirty years ago, and continues to expand today, carving out markets across Europe and into Russia. It has over 1,350 outlets and 60,000 employees in Germany alone, and Europe has emerged as a vital contributor to McDonald’s bottom line.

McDonald’s success is built in part on avoiding some of the miscues of Walmart. As noted earlier, management has been willing to adapt its business model, drawing on local expertise, relying on local ingredients, and preserving local architecture. Moreover, it exhibited flexibility, modifying its low-wage model, paying about double its US wages in Scandinavia, for example.88 Even so, old habits die hard; the firm has persistently endeavored to exploit loopholes to avoid paying more than the absolutely lowest wage.89

Europe tends to regulate by goals. Officials provide plenty of written guidance, but rely on firms to meet the spirit of those guidelines in a collaborative fashion. The presumption is that the business community will not seek to thwart public intent by legalistically exploiting regulatory leeway. American executives are schooled in the adversarial über legalistic US model, however, where lawyerly evasion is the modus operandi, and every comma, adverb, and adjective relentlessly parsed for wiggle room.

For example, McDonald’s established its own captive trade union and work councils, comprising mostly compliant store managers.* Other tactics include discriminatorily firing trade union supporters and slow-walking wage negotiations.90 In a frustrated France, the repeated use of these tactics caused courts to order the arrest of some McDonald’s managers.91

Other American firms like Amazon have adopted some of McDonald’s tactics. Amazon is a resounding commercial success in northern Europe. Sales have tripled since 2006 in Germany alone, with distribution centers at Bad Hersefeld, Rheinberg, Leipzig, and Werne employing as many as 9,000 temporary hires during busy periods. But management is apparently unhappy paying wages of €9.65 ($12) per hour, well above American wages.

To compress wages, both Amazon and McDonald’s aggressively game the government subsidized apprentice programs in northern Europe. Amazon exploits a German Federal Employment Agency subsidy, for example, where taxpayers fund the entire wage for the first two weeks for new employees; the German program is designed to avail firms a window to costlessly evaluate the suitability of new hires. Rules to prevent repetitive reemployment of the same men and women (at taxpayer expense) were thought unnecessary because such practices clearly violate the law’s intent. Amazon viewed that presumption as a loophole: as many as one-half of its workers are repetitive rehires, an abusive exploitation of the program that was termed “scandalous” by the North Rhine-Westphalia labor minister Guntram Schneider in 2010. The tactic saved Amazon €1 million in wages just in that one German state alone that year.92