CHAPTER 13

WAGES RISE IN FAMILY CAPITALISM

“If we are able to grow, as our German friends, the productivity of our economy, then of course we must increase wages.”1

CHRISTINE LAGARDE,

Former Economic Minister, France Managing Director, International Monetary Fund

“The share of every dollar of value added to the US economy going to American workers has also fallen to a record low of 57.1 cents in the US dollar, down from more than 62 cents before the subprime mortgage crisis, and well below an average of 63.9 cents in the previous century.”2

MALCOLM MAIDEN,

Sydney Morning Herald December 14, 2011

“Europe is often held up as a cautionary tale, a demonstration that if you try to make the economy less brutal, to take better care of your fellow citizens when they’re down on their luck, you end up killing economic progress. But what the European experience actually demonstrates is the opposite: social justice and progress can go hand in hand.”3

PAUL KRUGMAN,

Nobel Laureate, Princeton University

Mervyn Le Roy’s film I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang exquisitely captured 1932, the darkest and most despairing year in American economic history. Paul Muni is rendered bankrupt, jobless, and disgruntled by a malevolent government and callous society. The film contains perhaps the most evocative scene in American cinematic history, when Muni is unable to hock his Army medals because the pawnshop already had purchased too many.

Two years later, It Happened One Night became the only film ever to win all the major Academy Awards, even though it was far from Frank Capra’s best. He rejected the pessimism of I Am a Fugitive crafted early in the New Deal to present a message of optimism in One Night. Capra’s antagonist was a plutocrat who selfishly resists reforms initially, but its message was uplifting in the end, when Claudette Colbert’s wealthy father abandons his narcissism.

As the Great Depression persisted with despair deepening, Capra revised his narrative again in his best work, the nuanced Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).4 The plutocrat businessman Edward Arnold remains corrupt to the end, bending government to his bidding and forcing the hero James Stewart and moviegoers alike to confront the enormous challenge and complexities in bestowing economic sovereignty on families. Capra taught that Aristotelian democracy is possible in America only if voters are willing to struggle mightily to attain it. Even today, audiences react to its powerful emotive message: only a visionary sense of community can overcome a society dominated by a greedy and cynical extractive elite.

Both American and northern European families have been on a journey since those dark days, but their destinations have proven quite different. The American journey, which began so brightly with the postwar flush of prosperity, has ended badly. Why? Blessed with abundance and a sense of exceptionalism that lured too many to believe that One Night portrayed reality, it was much easier for Americans to be misled by politicians. In contrast, jaundiced voters in northern Europe were not so foolish to believe that family prosperity was a default setting for capitalism. Scarred by pitched street battles with communists, Weimar inflation, the Depression, and devastating war, voters there knew firsthand the ghastly terror, anger, and frustration of Paul Muni’s character. They knew far too well the shortcomings of democracy to believe that innate goodness resides in its DNA, as Capra argued in One Night. Unlike Americans, they had learned what economists Daron Acemoglu of MIT and James Robinson of Harvard concluded in Why Nations Fail, that episodes of broadly based opportunity for innovation, entrepreneurship, and prosperity are so rare in economic history over thousands of years that they can be counted on the fingers of one hand. They are absolutely not default settings for capitalism or any other economic system in America or anywhere else.

Europeans knew the manipulative Edward Arnold—and far worse—was reality, which is why, after World War II, they voted to craft a new and clever capitalism that granted economic sovereignty to families, not firms. Moreover, beginning in the 1950s, they adopted Jean Monnet’s vision of a common market in hopes of escaping the continent’s baleful history of war and bloodshed.

His goal was to dilute nationalism by coalescing economic and trade interests within Europe to render war less likely.5 Monnet realized that relying on economics to defuse nationalism had failed, nowhere more harshly and recently than in Europe. In 1909, the Daily Mail’s Norman Angell had published Europe’s Optical Illusion, arguing that with intertwined economic and credit ties among the Great Powers, even the winner of war would be worse off.6 Austrian Stefan Zweig’s sobering and poignant 1942 autobiography, The World of Yesterday, rejected the faux security described by Angell and others. The great nineteenth-century wave of European globalization and wealth creation had failed to prevent the bloodiest thirty years in history. Zweig wrote of the optimistic era prior to the Archduke Ferdinand’s assassination in 1914, which sparked World War I. In Belle Époque Vienna,

“There was as little belief in the possibility of wars between the peoples of Europe as there was in witches and ghosts…. Our fathers honestly believed that the divergences and boundaries between nations and sects would gradually melt away into a common humanity…. Now that the great storm has long since smashed it, we finally know that the world of security was naught but a castle of dreams; my parents lived in it as if it had been a house of stone.”7

Converting Zweig’s ephemeral castle to stone in post–World War II Europe required economic unification to create stability. With fears of the expansionist Soviet Union providing a wind at his back, Monnet evolved unification bit by bit, beginning with Europe’s coal and steel industries. He built his castle on the philosophy of Adam Smith, relying on the invisible hand of the market to allocate resources most efficiently. As Mark Leonard, director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform, explained in 2005:

“Monnet’s genius was to develop a ‘European invisible hand’ that allows an orderly European society to emerge from each country’s national interest…. He did not try to abolish the nation-state or nationalism—simply to change its nature by pooling sovereignty.”8

The Emergence of Family Capitalism

The genius of Adam Smith was not in his depiction of the age-old market process for allocating resources, but the much more nuanced melding of human nature and careful government regulation to sketch how markets can best be corralled and exploited to nourish mankind. Australia and the northern Europe economies have implemented Smith’s vision: mankind doesn’t serve markets in the fashion of the Reagan era, but rather is served by markets. The dictates of the marketplace and age-old greed are yoked to the higher priority of nurturing society and families.

Family prosperity is the postwar national covenant of the family capitalist countries, because citizens have been given clear choices at the polls and they’ve logically chosen self interest. Selfish voters have implemented Adam Smith’s dream of markets serving mankind by voting for public institutions and policies to institutionalize family economic sovereignty as national covenants. They strive at every election to implement the lesson Capra taught in Mr. Smith.

In contrast, Americans have voted since 1980 to shift economic sovereignty to the business community. Like families in fin de siècle Vienna, American voters by 1980 had come to believe—erroneously—that their golden age was built of stone rather than sand. Your parents or grandparents mistakenly believed that family prosperity was America’s default position, seemingly destined to persist regardless of choices at the poll. In reality, history teaches that the Aristotelian elites described by Acemoglu and Robinson virtually always extract all the gains from growth. The default setting for families since the beginning of time is to be victimized just as Americans have been under Reaganomics by those Adam Smith called “merchants and master manufacturers.”

Half a world away in Australia, voters also have avoided the American illusion that broadly based prosperity is the default setting for capitalism. Instead, like northern Europe, both conservative and liberal governments have labored to institutionalize stakeholder capitalism, featuring a nationwide wage determination system along with collaborative worksite environments. And also like northern Europe, but unlike America, the consequence has been real wages that have risen apace with productivity.

Wages and Productivity

Throughout history, wages have been what landowners, entrepreneurs, or owners of capital said they were. Rising real wages were rare, except for specialists, medieval guilds, or when plagues or other catastrophes caused labor shortages. Wages were highest at the economic height of Rome in the first century AD, late medieval England, and perhaps also in eleventh-century Kaifeng, capital of the Song dynasty, when early manufacturing specialization raised labor demand.*

The trump card wielded by employers systematically began to weaken only as productivity and labor demand rose for workers in the pottery, textiles, and other industries at Stoke-on-Trent, where the miraculous eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution began. Adam Smith was mesmerized by the productivity at a pin factory, for example, and concluded that wages had begun to be influenced by skill and education, rather than brute employer market power alone. Historian Ian Morris explains:

“By about 1830, these investments were making the mechanically augmented labor of each dirty, malnourished, ill-educated ‘hand’ so profitable that bosses often preferred cutting deals with strikers to firing them and competing with other bosses to find new ones.”9

Rising wages in the two centuries since lulled many into believing that wages naturally reflected value added by employees. Had the law of supply and demand been negated, as they thought? Would employees instead be paid according to their productivity level? This issue has dogged economics since the early industrial revolution, when data first began to appear regarding wages and productivity and inspired a series of famous (among economists) debates during the 1880s: Alfred Marshall faced down enthusiasts of Henry George and John Stuart Mill, who believed that competition among workers always had the potential to cause stagnating or declining real wages regardless of rising productivity. Marshall demurred.10 Armed with decades of statistics from the era of labor shortages created by the industrial revolution then driving up real wages, Marshall argued that private property and competition were succeeding in raising wages where socialism could not.

The outcome was that a wage-productivity link became standard theory among economists. This presumed linkage between wages and productivity was also credentialed by the iconic American automaker Henry Ford, whose legacy remains embodied in the Australian wage mechanism of the rich democracies today. Here is how New York Times Washington bureau chief David Leonhardt described that legacy in 2006:

“Henry Ford was 50 years old, and not all that different from a lot of other successful businessmen, when he summoned the Detroit press corps to his company’s offices on January 5, 1914. What he did that day made him a household name…. Mr. Ford announced that he was doubling the pay of thousands of his employees, to at least $5 a day. With his company selling Model T’s as fast as it could make them, his workers deserved to share in the profits, he said. His rivals were horrified. The Wall Street Journal accused him of injecting ‘Biblical or spiritual principles into a field where they do not belong.’ The New York Times correspondent who traveled to Detroit to interview him that week asked him if he was a socialist.”11

Ford could pay higher than market-clearing wages, because the productivity of his workers was relatively high; a Model T was produced every twenty-four seconds, compared to 12 hours previously.12 Better productivity performance also enabled Ford to grow fabulously rich, despite paying better wages than his competitors. Malcolm Gladwell has concluded that Ford is the most successful auto man ever and the seventh richest person in history, resting between Andrew Mellon and the Roman Senator Marcus Crassus.13 He was no fool, producing 15.5 million model Ts and revolutionizing the global auto industry; Ford certainly didn’t become wealthy overpaying for anything. This quintessential capitalist recognized that wages, based on value-added rather than market forces, were affordable—and even vital—in ensuring the prosperity of both his empire and of America:

“Our own sales depend in a measure upon the wages we pay. If we can distribute high wages, then that money is going to be spent, and it will serve to make storekeepers and distributors and manufacturers and workers in other lines more prosperous, and their prosperity will be reflected in our sales…. Countrywide high wages spell countrywide prosperity.”14

Henry Ford was a ferocious capitalist, but realized more was at stake than his own bank account. Higher wages meant greater economic prosperity. And his logic has prevailed in family capitalism nations such as Australia, as explained in this June 2010 editorial in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“… businesses in a market economy depend on consumer confidence and spending. Nothing hurts more than workers who can’t make ends meet. Every cent that goes to low-paid workers will be spent, whereas freezing wages can only cause consumer spending to contract.”15

Rising productivity results from the efforts of both employees and employers. Employers such as Henry Ford or General Motors provide most tools, equipment, and machinery in the workplace, which is an important determinant of productivity. Tim Slaughter’s information technology boss in Detroit certainly provided him computers and software. Likewise, the education, job skills, work ethic, talent, suggestions for improvement, and skill upgrading that employees such as Augustine, Tim, and you and I bring to the workplace are also important contributors to productivity. Making productivity rise is a shared project between employees and employers pulling together and jointly improving efficiency.

During most of the industrial era, some sizable portion of such efficiency improvements have been shared between employers and employees, just as Adam Smith and Alfred Marshall presumed. But the whole story is more nuanced and less encouraging—a lot less encouraging. It turns out that productivity growth is a necessary, but not sufficient, determinant of wages. Rising productivity spreading from the eighteenth-century Midlands across the globe didn’t repeal the law of supply and demand after all. Certainly during the golden age, and during the previous two centuries when labor markets were tight, Alfred Marshall’s marginal value theory was a reasonably accurate depiction of labor market realities, with wages rising more or less apace with productivity. In America, for example, Augustine reaped high wages in Detroit as his productivity increased—just like the theory predicted.

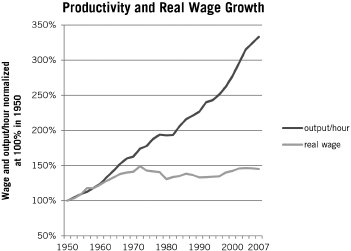

That ceased beginning in the 1970s. During the Reagan era, Washington stood by passively as offshoring, “us vs. them,” international wage arbitrage, and weaker trade unions tilted the balance of power in worksite negotiations in favor of employers. American men and women have continued to do their part, finishing high school or college, becoming better educated and adept at information technology, working harder and more productively. Yet wages became delinked from productivity, as depicted in Chart 13.1.

Chart 13.1. Real wage is average weekly earnings from 1950–1979 and wage component of Employment Cost Index 1979–2007. Output/hour is private nonfarm sector productivity growth.

Source: “National Employment Survey and Employment Cost Survey,” Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Adam Smith would have found that odd, because the American workforce is better educated and more productive today than ever in its history, yet wage earners for three decades have received little of the added bounty created. It would also stun Alfred Marshall, Smith’s successor as the greatest British economist, because it defied the generalized nineteenth- and twentieth-century experience and the shared presumption of economists across the political spectrum ever since. Even the most conservative economists endorse the wage-productivity linkage. Henry Hazlitt of the Austrian school of economic persuasions argued that “wages are basically determined by labor productivity.”16

Yet Smith and Marshall hadn’t confronted Reaganomics, which severed the productivity-wage link. Alfred Marshall would embarrassingly lose his debates today, which has sparked an extensive reexamination of the link by a host of economists, including Robert H. Frank and Phillip Cook, Edward Wolff, Robert Kuttner, Ian Dew-Becker, and Robert J. Gordon.17

The Reagan era Delinked Wages from Productivity

Not only did President Reagan and his heirs apparently not read Greek—no crime there—they didn’t appreciate the most iconic of all American capitalists, an embarrassing lapse for any US leader. Real wages rose during the remarkable American golden age economic renaissance after World War II to become the highest in the world because of Henry Ford’s perspective. And wages rise in the family capitalism countries today for the same reason, because their national covenant is to spread the bounty from rising productivity to all, beginning with employees. Here is how Berthold Huber, head of the large German IG Metall trade union, explained the centrality of linking wages to productivity growth: “A big part of our wage-setting formula is always productivity. It’s not the same in other nations.”18

It is certainly not the same in America.

A brief economics lesson: The income generated by an economy from one year to the next will rise for only two reasons. Population growth is the first. The other is productivity growth, which enables more to be produced with the same amount of effort. Both factors spurred the postwar American golden age, until 1973. Population growth averaged better than 1 percent annually. But much more important was the rapid and persistent growth in labor output per hour—productivity—which averaged 2.8 percent annually. That hefty rise in productivity was key to raising living standards. More could be produced with the same work effort, making productivity growth the standard for assessing genuine economic performance.

It was President John Adams who famously said, “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”19 Let’s begin with facts about wages in the generations since World War II. US agencies such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics conduct a handful of wage and labor cost surveys and they all depict the same story: inflation-adjusted wages rose handsomely until 1973, which turns out to be the peak year for wages in American history. During the rest of the 1970s, wages continued rising briskly, but inflation took away all of the gains, which caused real wages to sag.

Real wage stagnation continued after the Reagan era dawned in 1981, but the reasons why became different. Rather than stagnating because of inflation, real wages went flat because wages on offer from employers began growing far more slowly. Wages went flat as American employers chose to stop rewarding rising labor productivity. For most Americans, the outcome was wage increases that trailed slightly behind inflation. The only exception was about 5 percent of the labor force, especially those with graduate school and professional degrees, valuable skills, senior business executives, or bankers. Their earnings outpaced inflation. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Annual Real Wage Change

1950-1973 |

1979-2011 |

|

| Average wage changes: | ||

Earnings of all employees1 |

n/a |

+0.1 |

Earnings of middle/working class employees2 |

1.8 |

-0.1 |

| Median weekly earning3 | n/a |

+0.1 |

| Index: Productivity growth/year | 2.8 |

1.9 |

Table 1.

1 Wage and salary component of Employment Cost Index; survey began in 1979.

2 Current Employment Survey of real weekly average wages covers the lower paid 80 percent of all private sector employees (those in nonsupervisory and production occupations).

3 Fulltime workers; series began in 1979.

Source: Employment Cost Index, Current Employment Survey and Private Nonfarm Business Sector Productivity Series, http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/print.pl/lpc/prodybar.htm, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Wage data for middle- and working-class employees (nonsupervisory and production employees) is the most comprehensive private-sector time series across the entire postwar period. It excludes compensation paid to the top 20 percent of the American workforce, such as CEOs and other white collar and supervisory employees. Because this series includes the wages and salaries earned by the bottom 80 percent of all Americans, college and noncollege, male and female alike, it provides the most accurate snapshot of how most Americans working in the private sector have fared.

Real wages increased an average of 1.8 percent each year (nearly 50 percent overall) during the postwar decades through 1973, before hitting a stone wall. Total real labor compensation, which includes benefits as well as wages, performed better than wages alone, at least until 2004.20 But total compensation has gone flat since then as well, because employers have succeeded in capping benefit outlays after years of shifting pension and health insurance costs to employees. In combination with stagnant paychecks, this shifting has caused important out-of-pocket costs for health (co-pays, premiums, and deductibles), housing, child care, and education to now consume 75 percent of middle-class household incomes compared to only one-half of incomes back in the 1980s.21 This budget squeeze is why families in recent decades resorted to debt and the widespread breaching of retirement accounts like 401(k)s to meet household expenses.22 In recent years, about 28 percent of participants have borrowed against retirement, and 42 percent completely cash out pension funds when changing jobs.23

This epoch of wage stagnation is acknowledged by economists across the ideological spectrum. Details show that the Reagan-era erosion in earnings has been most severe among men, whose wages are down nearly 20 percent in real terms since 1980. About one-half of that drop is the result of pay lagging inflation, and the other half the result of an (unwelcomed) decline in annual work hours. Work has become less secure and more erratic, with millions of men cycling in and out of the labor force over the course of a year, unable to find full-time work because job growth has lagged workforce growth. For example, 94 percent of men between the prime ages of 25–64 worked in 1970, but only 81 percent worked in the recovery year 2010, the “new normal” of a weak economy that bedevils American families today. The hourly earnings of women performed better during the Reagan era but remain below male earnings.24

Productivity growth rates are also noted in Table 1. By comparing real wage growth and productivity growth, an approximation of how the gains from economic growth have been distributed can be determined. During the golden age, productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent annually and real employee wages rose about 1.8 percent, meaning employees received about 60 percent of that growth. That is how the greatest middle class in history was created. It explains how your parents or grandparents, along with Augustine, were able to leave farms and become solid members of the middle class, buy a home and a new car, take vacations, and step onto a career path. That outcome was responsible for driving poverty in America down to record low levels not seen since, enabling tens of millions of farm boys like Augustine and my father to live the American Dream.

The relentless rise in wages earned by these men and women across America made them equal beneficiaries with bankers and business executives of the wondrous American postwar boom. It breathed life into the American Dream. And this postwar model of stakeholder capitalism was studied intently and mimicked by Japan, Australia, and northern European nations eager to create their own flourishing middle classes after World War II.

America was heroic. It had managed to turn the genius of John Locke and Adam Smith into broadly rising prosperity for most, regardless of the meanness of their birth. And the broad rise in living standards from American stakeholder capitalism tossed socialism and communism into the dustbin of history.

Voters ended it all in 1980.

Wage Compression

This postwar span of America’s wage history has been studied by a host of economists including Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez.25 Their analyses tell the same story of robustly rising wages through the golden age, followed in the decades since by stagnation. For example, Isabel Sawhill, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and John Morton, director of the Economic Mobility Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts, examined the earnings of fathers and sons using data from the US Census Bureau. As a baseline, Sawhill and Morton looked at men who were in their thirties in 2004 and compared their incomes to their fathers’ at the same age in 1974. It is very likely that the males in your family were part of their giant database. They found that real median incomes of men in their thirties in 2004 was 12 percent ($5,200) lower than in 1974, vividly documenting how the Reagan era delinked productivity and hard work from wages.26

This pattern holds across all education levels. For example, the Economic Policy Institute concluded that the entry-level wage for men with secondary school diplomas was $11.68 per hour in 2010, down from $15.64 per hour in constant dollars in 1979. Moreover, as noted earlier, men and women with college degrees also earn less now, adjusted for inflation, than during the golden age. Among broad categories, only earnings of graduate school degree-holders are higher.27

The outcome since 1980 has been wage compression, the consequence of elements such as offshoring and short-termism, with mediocre jobs replacing good ones. It is exemplified by the anecdotal behavior we reviewed earlier of auto companies and firms such as Snapple Dr. Pepper. And it’s statistically documented extensively as well. The analysis noted earlier found that some 79 percent of the 6 million jobs lost in 2008– 2009 paid more than $13.84 an hour, yet only 42 percent of the jobs created in 2010-2012 paid as well.28 Moreover, in January 2011, the National Employment Law Project found that 40 percent of jobs lost during the recent recession were high-wage ones, but only 14 percent of the new jobs in the recovery paid the same high wage. In contrast, only 23 percent of jobs lost were lower-wage ones paying less than $15 per hour, but they comprised 49 percent of all new jobs.29

This degrading of America’s job mix confirms that little of the gains from growth during the Reagan era accrued to employees, with wages delinked from productivity. As we will soon learn in detail, such decoupling has not occurred since World War II in the other rich democracies. In the United States, the most recent previous episode was the Roaring Twenties when productivity grew 63 percent between 1920 and 1929, but real wages fell 9 percent.30 But that disconnect nearly a century ago was too brief to convince economists that the productivity-wage link portrayed by Adam Smith and Alfred Marshall had been severed.

By contrast, the current disconnect has persisted for three decades and counting, through recession and recovery—virtually the entire span of the Baby Boomer work experience. And unfortunately, it seems this delinking will persist until either policies are changed in Washington or a billion new high-value jobs are created globally, enough to create US labor shortages.

Wages and the Gains from Growth in the Family Capitalism Countries

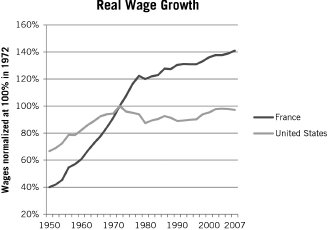

As we learned earlier, real wages have continued rising in the family capitalism countries, with paychecks closely mirroring the statistics on the cover (covering wages, benefits, and employer taxes for manufacturing blue-collar workers) as well as the French experience (just wages) depicted in Chart 13.2.31 The statistics on the cover depict a considerably larger rise than this figure because the full cost of French workers such as fringe benefits and government fees for health care and the like has outpaced the rise in wages alone.

Chart 13.2. The US series is average real weekly earnings (1950–1979) and the wage and salary component of the Employment Cost Index (1979–2007) for the private nonfarm sector. French wages are average wage index series net of government taxes for the private and semi-public sectors, and includes apprentices and trainees, but excluding government employees.

Sources: National Employment Survey and Employment Cost Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics; “Revenus-Salaires-Evolution du Salaire Moyen et du Salaire Minimum,” Insee, Paris, 2008.

The French data indicate that the growth rate of real wages slowed a bit after the 1970s, but has risen about one-half a percentage point annually since. You may recall the economists Piketty and Saez determined that wages of only 5 percent of American workers have outpaced inflation since then. In contrast, the average French employee over the entire span of the Reagan era has earned wage gains exceeding those received by 95 percent of Americans.

Other scattered wage data indicate that this French pattern of modest, but persistently rising real wages occurred in the other family capitalism countries as well. And it has continued in more recent years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). From 2001–2007, for example, inflation-adjusted, real average wages grew 4.2 percent in France (0.6 percent annually); 3.5 percent in Germany (0.5 percent annually); and nearly 10 percent in booming Australia (1.41 percent annually). In contrast, real median wages in the United States grew a minuscule total of only 0.21 percent (0.03 percent annually) during this same period.32

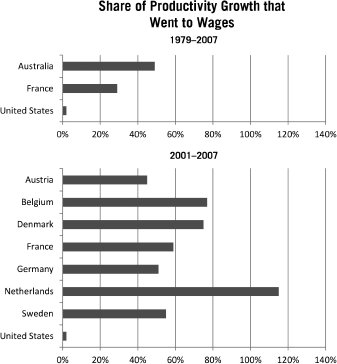

A moment ago we learned how the gains from growth were distributed in America during the golden age. Productivity and wage data can similarly be used to determine who reaped the gains from growth in the family capitalism countries during the Reagan era. The most comprehensive statistics over the long span of the Reagan era are from Australia, the United States, and France. In Australia, labor productivity rose about 1.6 percent annually between 1979–2007, according to the OECD, and real wages rose about half as fast; thus, about half of the gains from growth accrued to employees as higher wages. As depicted in Chart 13.3, about one-third of the rise in labor productivity was reflected in the paychecks of French workers over this span, while virtually none (< 2 percent) of the gains from growth was reflected in American wages during the Reagan era.

Compatible statistics for all the family capitalism countries are available for recent years from the ILO and are also reproduced in this figure. These data show that the robust share of employee gains from growth across these nations has continued to far outpace the American experience.

Chart 13.3. Average annual real wage growth as share of average annual productivity growth. US data is median weekly earnings for fulltime employees, in all industries, from 1979 to 2007, http://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet); average weekly earnings 1979–2006 for Australia; and median real wages 2001–2007 for the United States.

Sources: “Global Wage Report 2008/9,” statistical appendix, table A1, International Labor Organization, Geneva; “Employee Earnings, Benefits and Trade Union Membership 63100TS0002,” Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra; “Du Salaire Minimum et du Salaire Moyen (Net) Annuels Depuis 1951 (en Euros Constants), Salaries du Secteur Privé et Semi-Privée, y Compris les Apprentis,” Insee. Paris; US Bureau of Labor Statistics; and “Economic Outlook,” OECD, no. 82, December 2008.

There are relatively few share-of-growth analyses such as this one; the most comprehensive was published in October 2011 by economists Jess Bailey, Joe Coward, and Matthew Whittaker under the auspices of the British Resolution Foundation. They reached similar conclusions. Looking at full-time employees, they concluded that the portion of real GDP per capita growth reflected in US median wages has lagged far behind the Australian, French, or German share since 1980. Their commentary regarding the robust French experience, in particular for lower-wage groups, may strike most Americans as simply unfathomable in light of their own wage experience during the Reagan era:

“France may offer the best example of a country in which ordinary workers continue to prosper. That is, although wages at the median have fallen some way behind economic growth, this has [occurred] … because of a disproportionate increase in the wages of those at the bottom.”33

Since 2001, lower-paid French workers have received annual wage gains averaging 0.9 percent in real terms, which is 50 percent larger than French average national gains.34 Indeed, wage statistics suggest that Australia and France best embody the principle spelled out eloquently by John Rawls in 1971, likely America’s most prominent twentieth-century philosopher. The late Harvard professor argued that a society is most meaningfully judged by its treatment of the least advantaged.35 The best spots on earth to be born poor are Australia or France, the nations that come closest to fulfilling Adam Smith’s dream of prosperity for all mankind.

In 2012, the International Labor Organization statistics showed that labor income in Germany has stagnated in recent decades even as wages continued rising. This trend was a consequence of steadily rising real wages coupled with a sharp decline in hours actually being worked as employees there and elsewhere across northern Europe and increasingly affluent Australia substituted leisure for work.36

Leisure Instead of Work

Thorstein Veblen argued in his 1899 classic, The Theory of the Leisure Class, that employees will work long and hard to enable status-related conspicuous consumption. The northern Europe experience is evidence that supports this theory, if we view leisure time as a variant of conspicuous consumption. A more contemporary descriptor of attitudes in other rich democracies toward work and leisure is provided by the political scientist Andrew Moravcsik. He posits that Europeans have been more willing than Americans to substitute additional leisure for work as European wages rose; data confirm his hypothesis.37

In northern Europe, wages have risen steadily for decades, enabling folks to reduce their work effort at a measured pace without unduly forgoing income. The consistent quality of real-wage gains year after year in northern Europe is responsible for the trend toward more leisure and less work there. Wages roughly equal American wages, but the history of steady wage gains in the postwar era gave northern Europeans the confidence to reduce work effort in expectation that gains will persist in the decades ahead. No such expectation has existed in America since the 1980s, however. Here is how Barry Eichengreen contrasted the impact of these divergent trends on work effort in the United States and in Europe:

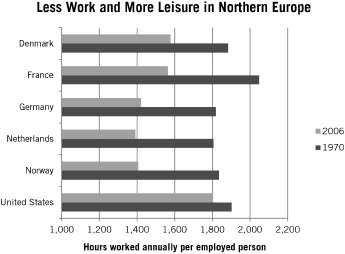

“Although hours [worked] had been falling since the mid-1960s, they had moved in tandem in the two economies, reflecting the common desire of workers to take some of their increased income in the form of leisure. After 1975, however, hours worked per employee stabilized in the United States, but in Europe they continued falling.”38

Back in 1970, as we see in Chart 13.4, northern Europeans worked about the same as or longer than Americans; French men and women, for example, worked over 2,000 hours annually or 7 percent longer than Americans, who were a third richer at the time. Since then, Europeans have reduced their work effort about 20 percent across the board as real wages continued rising, substituting more leisure. In contrast, yoked to their offices and factories by wage compression and job insecurity, Americans have been willing to pare back work hours a trivial 5 percent. For many, that reduction has been involuntary.

Chart 13.4. German data is for West Germany and for 1976.

Source: OECD Employment Outlook, 2007 Statistical Annex, Table F, OECD.StatExtracts.

Long Vacations

Australians and northern Europeans have more leisure than Americans, especially long vacations, as noted in Table 2. Fringe benefits are also higher in the family capitalism countries, where many employees routinely receive large year-end bonuses and more paid vacation days. In contrast, 23 percent of Americans receive no vacation or holiday time, and tens of millions are only paid for Christmas, New Year’s, or Easter if they work those holidays.39

Hours Worked and Benefits Paid to Employees

Bonuses1 |

Annual Paid Holiday Leave |

Hours Worked/Year |

|

| Australia | n/a |

20 days |

1,714 |

| Austria | 14.7% |

24.7 days |

1,655 |

| Belgium | 11.1% |

19.5 days |

1,571 |

| Denmark | 2.2% |

24.9 days |

1,577 |

| France | 12.3% |

30.9 days |

1,564 |

| Germany | 8.9% |

28.8 days |

1,436 |

| Netherlands | 9.5% |

21.9 days |

1,391 |

| Sweden | 1.4% |

n/a |

1,583 |

| United States | 2.1% |

8 days |

1,8042 |

Table 2. Hours worked data from 2006, paid leave and bonus data 2002.

1 Nonproduction-related bonus; amount paid as share of annual gross wage.

2 US national average, including public sector; private-sector average was 1,758 hours.

Sources: Hans-Joachim Mittage, “Statistics in Focus,” Eurostat 12 (2005); “Employee Benefits in Private Industry,” Employment Cost Index series, and “National Compensation Survey,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2006; Australian Bureau of Statistics; and “Economic Outlook 2007,” OECD, table F.

Wages in Northern Europe Likely Exceed American Wages

Earlier we learned that comprehensive labor costs paid by employers are $10 per hour higher in northern Europe. But these figures include social insurance taxes and fees, which are considerably higher in the family capitalism countries. How does pay in the United States compare if such taxes and also fees for health, pensions, and other benefits are stripped out? Americans certainly receive less health and pension coverage than Australians and northern European employees, but do they at least earn more than these folks abroad in wages and the cash value of paid leave and other direct benefits?

We can only speculate about wages across the board in all sectors internationally because of data limitations. However, the Bureau of Labor Statistics in Washington, DC gathers internationally comparable data on wages in manufacturing sectors. And we learned earlier that wage patterns in manufacturing are broadly representative of overall wages. So what does the BLS data show?

In 2010, the average value of wages, paid leave, and cash benefits for Americans in the manufacturing sector was $26.27 per hour. That was lower than the comparable figure for employees in every family capitalism country. The closest was manufacturing sector pay in France ($27.61 per hour). Comparable figures for Australia ($32.40) and the other nations in northern Europe, including Belgium ($34.30), Denmark ($42.40), Germany ($34.23), and Netherlands ($32.23) were notably higher.40

That means Reagan-era wage stagnation has been sufficiently severe so that manufacturing-sector employees in every family capitalism country—and probably employees in all sectors—now make more money than their US counterparts. Employees abroad also receive better (i.e., cheaper and more comprehensive) health care, enjoy secure pensions, and benefit from sending their youngsters to college tuition-free.