CHAPTER 16

THE OPPORTUNITY SOCIETIES OF STAKEHOLDER CAPITALISM

“Free market capitalism is … the engine of social mobility, the highway to the American Dream.”1

GEORGE W. BUSH,

President, November 2008

“The economics literature, based on correlation or regression coefficients, suggests that the United States may, indeed, be exceptional, but not in having more mobility, but in having less, a finding our results support.”2

MRAKUS JÄNTTI, et al,

University of Oslo, 2005

[College in America] “Rich, stupid children are more likely to graduate than poor, clever ones.”3

Economist,

April 17, 2010

[The dominant role of parental wealth] “… very manifestly displays the anti-meritocracy in America—the reproduction of social class without the inheritance of any innate ability.”4

DALTON CONLEY,

Director, Center for Advanced Social Science Research, New York University, December 2007

America is the only rich democracy in the twenty-first century where birth remains destiny—and I think it’s because Ronald Reagan never understood John Ford.

I can understand him not appreciating Jean-Jacques Rosseau, maybe John Locke, or even Frank Capra. But John Ford?

It’s all there in the greatest Western of all, My Darling Clementine. President Reagan loved his cowboys, especially stories about individual heroes like Wyatt Earp. He watched Clementine but didn’t see it, and proved clueless when it came to Ford’s evocative message. After all, it was the community that hired Earp and sparked the gunfight at the OK Corral, banding together in joint action to improve their lives by creating new opportunity, their eyes set on the future. In contrast, the politician Ronald Reagan chose to demonize the communitarian spirit and the notion that the business community has broad responsibilities to society. Like Ayn Rand, he glorified individualism—precisely the dark societal trade-off rejected by the greatest director of Westerns—over an individual’s responsibility to strengthen community. President Reagan empowered the narcissists among us, instead of the good citizens of Tombstone rightly deified by Ford.

In stripping economic sovereignty from families, Ronald Reagan mocked the concept of opportunity symbolized by the visionary families of Tombstone. By targeting minimum wages, promoting an Us vs. Them culture disinterested in productivity, upskilling, wages, or jobs, and shirking public commitments to education, poverty alleviation, sober monetary and fiscal policies, or trade unions, he undercut the precise policies that made golden age America the land of opportunity. Reagan savaged the only proven tools in the entire sweep of human history to expand opportunity. And in the process, his cultural shift abandoned the Republican Party’s historic focus on improving broad opportunity and reducing poverty.

The Myth of American Economic Mobility

Americans face sour economic prospects, but many retain a mythical sense of US prowess and mobility from the experience of their parents or grandparents. How could economic mobility not be high in America, they ask? After all, it was founded by settlers fleeing the rigid, class-rooted, economic, religious, and social elitism of England and continental Europe, societies where since time immemorial those born poor died poor, and those born rich died rich. This unfounded belief is perpetuated by politicians, such as former vice-presidential candidate and Congressman Paul Ryan:

“We are in an upwardly mobile society with a lot of movement between income groups. [In Europe] … top-heavy welfare states have replaced the traditional aristocracies, and masses of the long-term unemployed are locked into the new lower class.”5

Congressman Ryan is a leading Republican Party spokesman on budget issues and is known to substitute fiction for truth as when he said this at the Heritage Foundation. Politicians can do that, pandering to donors. The facts are that America has devolved into an inopportune society, its Reagan-era policies reducing opportunity by a quite large 40 percent.

The family capitalism countries have become the new land of opportunity. They pay the world’s highest wages. They consistently spread the gains from growth broadly, rewarding hard work with real wage gains. And they inordinately raise the incomes of lower-paid employees, thereby improving economic mobility. In spreading prosperity to the least advantaged, they meet the key test posed by philosopher John Rawls.

America flunks the Rawls test. France and Australia do the best of any nation in world history of meeting the Rawls standard. During the last two decades, rising real wages for low-income French employees have reduced their wage gap with the middle class.6 France even makes it cheap to hire minimum-wage workers; their employers pay a Social Security tax of only 2 percent. Economists at the UK Resolution Foundation in October 2011 concluded that France showed:

“… a substantial improvement in outcomes for the lowest paid, rather than a concentration of the proceeds of growth in the hands of the highest earners…. For example, in the decade to 2005, the proportion of employees below the low-pay threshold in France fell, with just 11 percent in this position at the end of the period, compared with 22 percent in the UK and 25 percent in the US. Similarly, while the real value of the US federal minimum wage declined significantly between 1970 and 2005, the French minimum wage doubled in real terms.”7

There are profound differences between Reagan-era America and the family capitalism countries, but perhaps the most significant is how they succeed where America fails in creating economic opportunity for the least advantaged at birth. The development of institutions to accomplish this surely ranks among the noblest accomplishments in human history. The judgment of Rawls renders them superior societies, as would the judgment of most economists, including Nobel laureate Amartya Sen of Harvard, who argues that families view the degree of economic mobility and opportunity as more important than actual income.8

One might think that the hyperflexible American markets for capital, venture capital, and labor, coupled with world-class innovation, years of robust profits, and superb university educations, would at least enable anyone with energy and diligence to prosper. It’s certainly a bedrock article of faith among many that your odds of beating the game, escaping even dodgy roots, and landing in Beverly Hills are better in America than in stodgy Europe. So many Americans believe this notion of exceptionalism that it entered national folklore. Moreover, too many seem willing to tolerate striking inequality, believing that opportunity remains available for anyone to succeed. Some 76 percent of respondents to a 2004 survey by Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, for example, agreed that most or all Americans have “an opportunity to succeed.”9 And The Economist carried a story in 2006 saying this about Americans:

“Eight out of ten, more than anywhere else, believe that though you may start out poor if you work hard, you can make pots of money. It is a central part of the American Dream.”10

That impression is based on history reaching back nearly to America’s earliest days. The colonization of America was a miraculous time when opportunity so rare in human history was available. Of course, this opportunity came at the expense of many millions of Native Americans murderously cast aside. Impoverished and youthful adventurers from Europe such as Abraham Smith arrived in seventeenth-century Virginia with only the clothes on their backs, owing six or seven years of labor to others who paid for their dangerous passage.11 But the promise was utterly breathtaking—and real: adventurers arriving penniless could become landowners (and voters, if male) in less than a decade simply by the sweat of their brow, privileges denied all but well-born males back home or at any other period in world history.

For many in the old countries, the impossibly rare character of the colonial economy defined opportunity. Dominating elites were less present than at almost any point in economic history, allowing grit, innovation, and entrepreneurship to flourish. Even those of the meanest birth could fulfill great ambition. Aspiring to success through self-improvement was a common outcome and became a defining feature of the American experience. Most of our parents did it. Scotsman Samuel Smiles wrote Self Help in 1859, encouraging the theme of personal improvement through hard work and grit.12 The famous American optimist Horatio Alger penned formulaic novels such as Strive and Succeed, popularizing the concept of success through individual effort, although always with a vital dollop or two of good luck along the way. Real-life examples are common in American history: Benjamin Franklin, Andrew Carnegie, John Henry Heinz, Phineas Barnum, and Henry Ford all rose from poor roots; Heinz and Ford even overcame bankruptcy to attain great success.

The belief in America as an opportunity society was realistic prior to the Reagan era, and supported by institutions and politicians across the voting spectrum. Ironically, while Reagan’s legacy is one of dwindling opportunity, Milton Friedman in 1955 worried that rising college costs would limit opportunity and “perpetuate inequalities in wealth and status.”13 He was prescient in fretting about excessive college costs, yet his ideological crusade of demonizing government and shifting economic sovereignty from families to firms has been vastly more damaging to opportunity than rising college costs.

Belief in this elemental aspect of American uniqueness is responsible for the expectation that, like Augustine in Detroit, everyone can live the American middle-class dream through hard work. And the mechanism of such rising opportunity is hard work rewarded through rising wages, which make all things possible: a spouse, a home, and a stable family life with children who can hope for a still better future. Though dimmed by a few years of stagflation, that American dream still glimmered brightly when Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, elected by voters who erroneously believed both prosperity and opportunity were their default positions as Americans. Ronald Reagan believed it, too, because his uplifting life story embodied the notion of the United States as a meritocracy where hard work, ability, and education inevitably produce rising wages and opportunity—even as his policies were making it mythical.

Think of the transformation in American opportunity during the Reagan era this way: The essence of American exceptionalism is not whether self-made success is possible, but whether that opportunity is open to most citizens rather than just a few of the plucky and lucky like Horatio Alger’s heroes. Has the Reagan era sustained the historic American promise of opportunity for all bequeathed it? The answer is a unanimous no from scholars.

To succeed today, American children need to pick their parents very, very carefully.

Poor American Economic Mobility

Americans have tumbled onto that truth after three decades of Reaganomics. In a nationwide poll for the Pew Economic Mobility Survey in 2009, some 55 percent of respondents acknowledged that “in the US, a child’s chances of achieving financial success is tied to the income of his or her parent.” And more than half believed that it will be “harder for [their children] to move up the income ladder.”14

In the past forty years, American wages have never regained their 1972 high. Alarmed by the implications for economic mobility, a host of economists have examined how well Americans in the intervening decades have been able to move between income groups during their careers.15 These expansive studies examined different time periods and looked at different population cohorts, but all reached the same conclusion: economic mobility in America is poor.

For example, government economists at the US Treasury Department in 2007 used income tax data to divide nearly 100,000 filers into quintiles: five equal-sized groups. They found that 42 percent of those men and women in the lowest quintile in 1996 were still there ten years later, highly indicative of poor mobility16; in a perfectly mobile society, only 20 percent would still be there. An analysis for the Pew Mobility Project by economist Julia B. Isaacs of the Brookings Institution reached the same conclusion. Isaacs compared income data for parents from the late 1960s with that of their children in the late 1990s and early 2000s.17 She also discovered that 42 percent of children from poor households ended up in the lowest-earning quintile a generation later as adults. A subsequent update by the Pew Mobility project released in mid-2012 found that trend continuing. Drawing on statistics from 2,200 families from 1968 to 2009 (admittedly a small sample), 43 percent of youngsters born poor remained in the lowest-earning quintile as adults.18

The odds may be high of youngsters born poor remaining poor as adults, but what are the odds of moving up? Treasury economists also examined the prospect of achieving the “rags to riches” story of American lore. They found that the odds of a poor person in America striking it rich and rising from the bottom quintile all the way to the top earning quintile ten years later was a scant 5.3 percent. The Pew Economic Mobility Project examined the same question and found that the share who accomplished that between 1994 and 2004 was 6 percent, and the 2012 update lowered that figure to a bare 4 percent. Only a handful of musicians, athletes, Nascar drivers, or a coterie of scholarship students in the Ivy League or Ohio State achieve the American rags to riches story today. Isaacs concluded:

“Contrary to American beliefs about equality of opportunity, a child’s economic position is heavily influenced by that of his or her parents. Forty-two percent of children born to parents in the bottom fifth of the income distribution remain in the bottom….The ‘rags to riches’ story is much more common in Hollywood than on Main Street. Only 6 percent of children born to parents with family income at the very bottom moved to the very top.”19

In Reagan-era America, if you are poor, you have a 43 percent chance of still being poor a decade or generation hence, and you have only a 1-in-17 chance of becoming rich. That’s not quite the very long odds of winning a lottery, catching on in the NBA or Hollywood, but they are quite weak odds nonetheless. In contrast, Isaacs found that 39 percent of children born to rich parents were themselves rich some forty years later; the figure was updated to 40 percent in 2012. In other words, the odds of an American child ending up rich are nearly seven times greater if he or she does a superior job picking parents. Mobility is a bit better for those children from the middle class. But opportunity is so poor for the bottom quintiles that Reagan-era America fails the Rawls test.

American Economic Mobility Has Deteriorated

Is Reaganomics to blame? Mobility may be poor, but has it at least remained stable or even improved during the three decades of the Reagan era? Again, the answer is no. To the contrary, Reaganomics has proven toxic to opportunity.

During the golden age, economic mobility improved. Economists Emily Beller and Michael Hout utilized data going back to the 1940s to compare the economic status of sons with their fathers. Economists frequently focus on fathers and sons, because female economics is heavily biased by marriage outcomes. Their work began when youths like Augustine first began to leave farms for assembly-line jobs in the industrial heartland as the golden age emerged. Beller and Hout concluded that parental income became less important to the economic success of men between 1940 and 1980, meaning economic mobility had improved.20

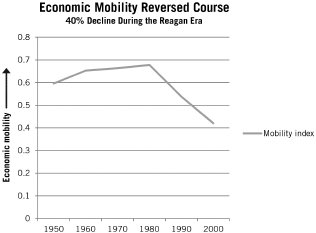

The arrival of Reaganomics changed all that. Since 1980, the economic status of a son’s parents has become more determinant and predictive of a child’s ultimate economic status. Plucky poor was out. Lucky rich was in. A sharp decline in mobility since 1980 has been documented extensively by economists. In 2002, for example, Kathleen Bradbury and Jane Katz looked at the impact of Reaganomics decade by decade since the 1970s and found that mobility had declined steadily.21 Perhaps the most extensive analysis of mobility trends in the twentieth century was performed in 2008 by Federal Reserve Bank economists Daniel Aaronson and Bhashkar Mazumder. Using six million data points from decennial censuses, they used the Beller-Hout formulation to evaluate the economic status of middle-age sons and their fathers at the same age. Their discouraging findings are reproduced in Chart 16.1.

Chart 16.1. Mobility is (1 minus the estimated intergenerational earnings elasticity coefficient implied for 40- to-44-year-olds. A mobility index of zero indicates a boy’s position in the income spectrum as an adult will be identical to his father’s forty years earlier; a value of 1 indicates a completely mobile society, where a son’s eventual status bears no relationship to his father’s income, and his odds are the same of becoming rich, poor, or anywhere in between.

Source: Daniel Aaronson and Bhashkar Mazumder, “Intergenerational Economic Mobility in the United States, 1940 to 2000,” The Journal of Human Resources 43: 1, table I (2008).

Aaronson and Mazumder concluded:

“We find that mobility increased from 1950 to 1980 but has declined sharply since 1980…. [It’s lower] now than at any other time in the post World War II period.”22

These studies provide the weight of scholarly evidence that the opportunity of Americans to bootstrap themselves like Horatio Alger’s heroes through education and hard work has deteriorated sharply during the Reagan era to the lowest level in more than 60 years. If not born rich, boys and girls have had to resort to the thin reed of diminishing opportunity to improve their lot, relying on weakening schools, indifferent if not hostile employers, rising college costs, and limited upskilling opportunity.

Since 1980, America has been transformed into a society that works in reverse: the poor are less likely to become rich, and the rich less likely to become poor. And that trend is cemented by rising income inequality, which limits the ability of lower-income parents to nurture childhood achievement. With schools in working-class neighborhoods under-resourced, college costs rising, and good jobs shrinking, working-class youths have grown cynical and pessimistic, increasingly sidelined by the Reagan era’s diminishing opportunity. Innate ability, height, education, grit, sex, ethnic origin—nothing comes close to parental wealth in determining the economic opportunity for youth today. As Michael Kinsley concluded in June 2005,

“The problem in short may not be that reality is receding from the national myth. The problem may be the myth.”23

Even before the recession and the 2012 election, a sense of diminished prosperity and a darkening future was palpable among voters, with Kinsley explaining it was becoming easier every day to slip out of the middle class from just bad luck, like an accident. Too few blame Reaganomics, even though only a bare handful of its acolytes and supporters have matched their opportunity society rhetoric with deeds. Most prominent is the late Congressman Jack Kemp, nominated for vice president at the Republican Party’s 1996 convention. He spoke glowingly of expanding opportunity, pointing to education and better housing as key measures of economic justice. As noted by Michael Gerson, a speechwriter for George W. Bush, Kemp argued that opportunity “is the most important measure of economic justice; capitalism is perfected by the broadest possible distribution of capital.”24 Kemp seems to have read his Aristotle, Adam Smith, and perhaps even Rousseau. But he was nearly a lone voice in the Republican Party.

It may surprise you, but evidence of reduced opportunity has become so persuasive that even conservatives get butterflies about the impact of Reaganomics on mobility. Here is how Stuart Butler, vice president for economic studies at the business lobby Heritage Foundation, put it:

“It does seem in America now that for people at the very bottom it’s more difficult to move up than we might have thought or might have been true in the past.”25

What really may be causing them to blush is that evidence of dwindling American opportunity in the Reagan era has gone viral globally; the United States is now routinely fingered as a cautionary tale when compared to the higher mobility in other rich democracies. Here is how economists Jo Bladen of the London School of Economics, Paul Greeg of University College, London, and Stephen Machin of the University of Bristol put it in 2005: “The idea of the US as ‘the land of opportunity’ persists; and clearly seems misplaced.”26 Experts at the OECD writing in the 2012 survey of the United States put it this way:

“… socioeconomic background has a much greater impact on student outcomes in the United States than it does in most other countries, resulting in much wasted talent.”27

Greater Economic Mobility in the Family Capitalism Countries

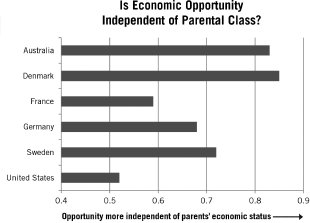

Responding to a wave of international analyses in recent years, economists have concluded that Kinsley and other researchers are correct: the notion of exceptional American opportunity not only has become mythical, experience since 1980 has turned that presumption upside down. Not only has mobility declined quite significantly, that decline has made American opportunity the lowest and weakest of any rich democracy, a national humiliation. “It’s becoming conventional wisdom that the US does not have as much mobility as most other advanced countries. I don’t think you’ll find too many people who will argue with that,” concluded Isabel Sawhill in January 2012.28 Studies informing that consensus include a number conducted in recent decades and evaluated in 2006 by economist Anna-Cristina d’Addio for the OECD.29 The d’Addio conclusions are reproduced as Chart 16.2, drawing heavily on researchers led by Mrakus Jäntti at the University of Oslo and Professor Miles Corak at the University of Ottawa.30

Chart 16.2. 2006. Mobility measure ranges from 0 to 1.0 and the variable is (1-estimated intergenerational earnings elasticity coefficient). High values denote greater economic mobility, with adult status more independent of parental status a generation earlier.

Source: Anna-Cristina d’Addio, “Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantage: Mobility or Immobility across Generations? A Review of Evidence for OECD Countries,” OECD, 2006.

This chart depicts the extent to which earnings of adults differ from parental earnings a generation earlier. The family capitalism countries, along with nations such as Canada, Norway, and Finland, have high economic mobility and notable churning of individuals among income categories from one generation to the next; earnings of children display a wide variation compared to their parents. These are genuine opportunity societies, where pluck and skill determine outcomes and one’s success bears little relationship to the economic status of one’s parents. Indeed, economic mobility or opportunity in nations such as Australia and Denmark is nearly 50 percent greater than in the United States. These enormous differences, documented in the d’Addio compendium, were highlighted by the Economist:

“Several new studies show parental income to be a better predictor of whether someone will be rich or poor in America than in Canada or much of Europe. In America, about half of the income disparities in one generation are reflected in the next. In Canada and the Nordic countries, that proportion is about a fifth.”31

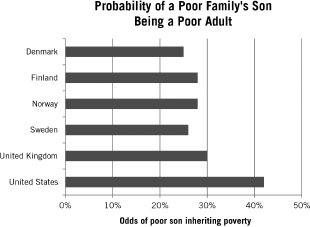

D’Addio also assessed mobility by determining the prospects of poor sons remaining poor as adults. Recall the US Treasury Department economists and Brookings Institution’s Julia Isaacs, who concluded that about 42 percent of adult sons from poor parents in America also were poor. As depicted in Chart 16.3, these US odds are considerably worse than in any other rich democracy, almost double that of Denmark. This chart displays the probability that the son of a father in the lowest quintile will land in that quintile as an adult. Even in the class-ridden United Kingdom, cluttered with moneyed blue bloods of title and wealthy global expatriates, the odds of remaining poor are 30 percent. In fact, sons born into low-earning households in any of the other rich democracies examined have quite significantly better opportunities to escape an impoverished birth than do American boys.

Chart 16.3.

Source: Anna-Cristina d’Addio, “Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantage: Mobility or Immobility Across Generations? A Review of Evidence for OECD Countries,” Paris, OECD, table 1, 2006. This data based on Jäntti, et al. University of Oslo, 2006.

You can see why Isabel Sawhill has concluded that “a number of advanced countries provide more opportunity to their citizens than does the United States.”32

The low and declining American intergenerational mobility is most pronounced where it is most meaningful, pinning far too many children from lower-income households in what has become a multigenerational cycle of poverty. Here is how the University of Oslo economists describe that consequence of Reaganomics, including their quote in the epigraph to this chapter:

“Comparative studies of socioeconomic mobility have long challenged the notion of ‘American exceptionalism,’ a term that was invoked by Tocqueville and Marx to describe what was then thought of as exceptionally high rates of social mobility in the United States … the United States has more low-income persistence and less upward mobility than the other countries we studied…. The probability that the son of a lowest-quintile father makes it into the top quintile group—‘rags to riches’ mobility—is lower in the US than in all other countries…. These two findings—higher low-income persistence and a lower likelihood of rags-to-riches mobility—seems to us quite powerful evidence against the traditional notion of American exceptionalism consisting of a greater rate of upward social mobility than in other countries. In light of this evidence, the US appears to be exceptional in having less rather than more upward mobility.”33

After thirty years of the Reagan era, the only American odds higher than a rich man’s son becoming rich himself as an adult are the odds of a poor man’s son staying poor. And the worst odds of all? The likelihood that opportunity will enable a poor man’s son to become rich. Of all the world’s rich democracies, America is the worst poor son’s country, and the best rich son’s country.34

The American Education Auction: Widening Class-Based Disparities

Birth is destiny in America, but not in the family capitalism countries, which are the true contemporary opportunity societies. Their public policies have been instrumental in this success, especially institutional arrangements such as codetermination that generates good jobs and upskilling to ensure employees have the skills to qualify for such jobs. For families, high wages have resulted from Australian-style national wage policies, supported by quality education, free college, and public upskilling programs; those programs enable most families to invest more effectively in their children’s future than resource-deprived American families.

Almost from birth, a web of mutually reinforcing policies, including preschool, childcare programs, and nationwide student spending standards, are utilized to create and enhance human capital while minimizing poverty. Remarkably, 89 percent of German three-year-olds attend preschool (two-thirds are private), as do 96 percent of four-year-olds.35 In contrast, only 69 percent of American four-year-olds are enrolled in early education, ranking the United States in twenty-sixth place in the world. Participation is greater in Austria (89 percent); Belgium (99 percent); Denmark (98 percent); France (100 percent); the Netherlands (100 percent); and Sweden (94 percent), according to the OECD.36 And the same pattern persists for five-year-olds. In Germany, every youngster is guaranteed a kindergarten spot, and OECD statistics show 97 percent are in public or private facilities in contrast to 80 percent in America. Comparable figures for Australia, Belgium, and the Netherlands are 99 percent.37

Economists including Tarjei Havnes at the University of Oslo and Magne Mogstad with Statistics Norway have determined that such preschool investments yield big payoffs for society. Writing in the 2011 American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, they concluded:

“… subsidized child care had strong effects on children’s educational attainment and labor market participation and also reduced welfare dependency. Subsample analyses indicate that girls and children with low-educated mothers benefit the most from childcare.”38

Similar evidence is provided by for a National Institutes of Health analysis; preschool interventions with low-income children in America were determined to generate anywhere from $4 to $11 in benefits per dollar invested.39 Even so, the more limited US availability of preschool support is symptomatic of a generalized American problem of uneven and limited access to internationally competitive education. Ironically, education has served in the past as an opportunity escalator for Americans, but quality education has become a luxury item in the Reagan era, with college and the price of neighborhoods featuring good public schools well outpacing wages. Recall economist Robert H. Frank had concluded that families must devote 60 percent more work hours now than they did in 1970 to afford neighborhoods with above-average school systems. Moreover, school districts exacerbate the resource disparity by assigning the most capable veteran teachers and principals to higher-income neighborhoods, according to a November 2011 report by the US Department of Education.40

Education attainment improved dramatically during the nineteenth century and through the 1970s, but the auctioning of education opportunity during the Reagan era has reversed this trend. There is considerable evidence that a class-based education gap has been exacerbated rather than eased by Reaganomics. Current research by education statisticians like Sean F. Reardon document that the achievement gap between students from impoverished versus higher-income families has widened in recent decades; the standardized testing score gap between rich and poor children is 40 percent larger now than in 1970, for example.41 And, National Assessment of Education Progress studies have concluded that 40 percent of reading score variations and 46 percent of math score variations among the states today are associated with childhood poverty. Indeed, poverty now easily trumps race as the more potent indicator of low achievement; the poverty/achievement gap is 50 percent wider than the gap between black and white youngsters.42 And here is how Isabel Sawhill describes the conclusion of her recent research into this area:

“An examination of preschool, K-12, and undergraduate and graduate education in the United States reveals that the average effect of education at all levels is to reinforce rather than compensate for the differences associated with family background and the many homebased advantages and disadvantages that children and adolescents bring with them into the classroom. There is no reason to expect change in the disappointing effect of education on economic mobility unless reforms are aggressively pursued at all levels.”43

Class-Based College Opportunity

Rising college costs have contributed to this class-based deterioration in education opportunity. The Economic Mobility Project of the Brookings/Pew analysis examined the impact of a college degree on mobility. Recall our earlier evidence that the odds of a poor son jumping to the top-earning quintile as an adult are 6 percent or less? If they finish college, those odds triple to 19 percent.44 The troubling news is the increasingly class-ridden nature of American society means children from resource-deprived schools, neighborhoods, and homes have only modest opportunity to attend college or to succeed once there. The brightest youngsters from poor backgrounds have opportunity, but few of their siblings or classmates do.

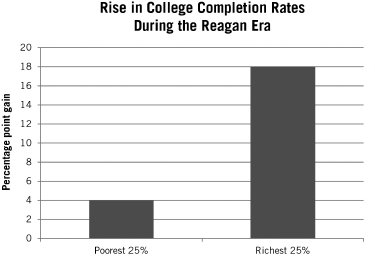

While college completion rates for all youngsters increased during the Reagan era, virtually all the rise was among students from higher-income households, with the gap between rich and poor widening quite significantly. The statistics responsible for this conclusion are disheartening, especially for a nation priding itself on educational opportunity. Only 5 percent of youngsters born in 1961–1964 to families in the lowest-quartile (25 percent) income group completed college, compared to 36 percent of youngsters born those years into the highest quartile. Yet the completion rate for the lowest-income youngsters growing up in the Reagan era (born at its cusp in 1979–1982) is only 4 percentage points higher, or 9 percent total. But the completion rate for those born into the highest-income quartile soared 18 percentage points at the same time, to 54 percent total. Thus, during the Reagan era, the increase in college completions by richer youngsters was four and one-half times greater than for poor youngsters, as depicted in Chart 16.4. Thus, students from more affluent households completed college at a rate six times greater than students from the lowest-income quartile. And they do it faster, too. Students from highest-income households are eight times more likely than those from the lowest-income families to earn a bachelor’s degree by age 24.45 And these results parallel those reached by other researchers such as Ron Haskins, Harry Holzer, and Robert Lerman.46

Chart 16.4.

Source: Martha J. Bailey and Susan M. Dynarski, “Gains and Gaps: Changing Inequality in US College Entry and Completion,” NBER working paper no. 17633 (December 2011); “College Completion by Income and Year of Birth,” Inequality in America, The Stanford Center for Poverty and Inequality, September 2012.

The actual situation is worse. A Century Foundation Report in 2010 concluded that 44 percent of low-income students with high standardized test scores enroll in four-year colleges, while 50 percent of those from high-income households but with only average test scores enroll.47 And the world knows it. The US college education system was captured editorially by the Economist magazine in April 2010, as indicated by its epigraph to this chapter:

“Rich, stupid children are more likely to graduate than poor, clever ones.”48

The outcome is that American college attainment in relative terms is deteriorating. The share of Americans from 25 to 34 years old with college degrees ranks only 14th among the richest nations, lagging behind nations such as Australia, Canada, France, Korea, and Norway.49 The US attainment rate used to be second, behind only Canada.50 And some believe the outcomes and performance in higher education today have ceased improving in absolute terms. David Brooks concluded in 2008 that “the US needs a more skilled workforce, but for the first time in our history, it is getting a generation no better educated than its parents.”51

Public policy has failed to slow the class-based consequences of the US education auction. Lacking family resources of the more affluent, capable poor and middle-class college students are penalized by inadequate public education support. Pell Grants for low-income students covered 72 percent of costs at a public university in 1976, for example, compared to only 38 percent in 2003; and that trend has worsened since with the downturn.52 Students have compensated by going heavily into debt with student loans.

American competitors abroad are not so foolish as to squander the talents of deprived but capable youths by diverting resources to give $46,000 tax cuts to millionaires.

The American Multigenerational Poverty Cycle

Stagnant wages, a weak minimum wage, and the disposable labor syndrome at worksites feature prominently in the disjointed life of lower-income families. The blight of impoverishment afflicting the chronically underemployed in many, if not most, instances reflects a life bereft of quality employment opportunities, a reality ensnaring more of the middle class each year. The genesis in many instances is not dysfunctional homes or inappropriate work habits, but insufficient jobs and especially insufficient jobs paying livable wages, which create or dramatically exacerbate family pathologies.

Evidence comes from three sources:

First, America is a low-wage country lacking sufficient quality jobs. ILO statistics reveal that nearly one-fourth of US jobs paid less than two-thirds the median hourly wage in 2010; this US rate is four times the incidence of low-wage jobs in Sweden, double the rate in New Zealand, and 50 percent higher than Australia’s. Worse, this comparison was just among full-time workers, which minimizes the actual incidence of crummy American jobs, many of which are temporary or part time.53 America really is a low-wage country and socioeconomic outcomes merely reflect that.

Second, the absence of quality jobs creates pathologies. For example, an important element creating the multigenerational poverty cycle is teenage pregnancies. Demographers have found that the incidence of teen births is linked to unemployment. Cynthia Cohen, Arline Geronimus, and Maureen Phipps, for example, concluded in a study in the journal Social Science and Medicine that declining jobless rates in the 1990s explained 85 percent of the drop in rates of first births to 18- and 19-year-old African Americans. That cohort is among those most prone to teen pregnancies. “Young Black women, especially older teens, may have adjusted their reproductive behavior to take advantage of expanded labor market opportunities,” was their conclusion.54

Third, impoverished Americans work very hard. Research conducted by economist Timothy Smeeding, while director of the Center for Policy Research at Syracuse University, produced the smoking gun. The poverty expert discovered that poor American families with children work more annual hours than families in any other rich democracy, yet they earn less, and too little to escape poverty:

“The United States also has the highest proportion of workers in poorly paid jobs, and the highest number of annual hours worked by poor families with children….”55

If hard work was the key to success in Reagan-era America, the poor would be atop the income pyramid. They are poor because they are paid low wages in insecure jobs, despite working hard. Their impoverishment is the consequence of too few good jobs, not deficient work efforts or inappropriate family cultures.

Already losers in the education auction, education attainment by students in lower-wage households is further weakened by frequent relocations. Scholars have found that it is common for lower-income families to relocate many times in a single school year, disrupting family environments for childhood learning as youngsters repeatedly adjust to new teachers, new curriculums, and new friends. Little appreciated by economists, the US-disrupted education syndrome is described this way by David Kerbow, a University of Chicago education researcher:

“Such house-hopping and school disruption is common in low-income urban areas across the country, with annual turnover of students typically ranging from 30 percent to 50 percent.”56

Thirty to fifty percent means little education is occurring. Turnover at one school in hard-pressed Flint, Michigan, reached an astounding 75 percent, noted Kerbow. New York Times reporter Erik Eckholm explains:

“Children switch from school to school, even returning repeatedly to the same one, as their parents become overextended on rent in one place, try another rental, flee an unsafe block, or move in with a relative or a new partner.”57

With the poorest intergenerational mobility and weakest opportunity of any rich democracy, America is plagued by inherited poverty: American youngsters with poor schooling are destined to become disposable workers, like their parents, a squandered resource, their genius lost. And their plight is exacerbated by a weakened economic safety net. President Clinton’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families reform, which appeared remarkably innovative in good economic times, has been revealed as senselessly cruel and draconian when times toughened. In 1996 before the changes, 68 of every 100 impoverished families with children received welfare support; by 2010, the share had plunged to only 27 of every 100 families, despite unemployment doubling.58 Intended to incentivize job searches, the reforms fail when the need is greatest: in the real world, employment opportunities collapse when the need is greatest, with five or ten applicants for every opening. The Clinton reform is like a car whose headlights cease functioning at dusk.

New Research Debunks Traditional Beliefs: Nurture Trumps Nature

Why are Americans indifferent to the multigenerational poverty cycle, leaving 20 percent of the United States chronically mired in or near poverty, and 20 million living in extreme poverty? Certainly, stagnation of real incomes amid rising costs for health, education, and other necessities makes families disinclined to support taxes. But responsibility for this indifference among voters also rests in some measure on their belief that the disadvantaged are a natural and ineluctably ordained phenomenon. The success of family capitalism countries in building genuine opportunity societies from top to bottom proves those beliefs erroneous. Poverty is permitted, not ordained.

Education expert Paul Tough argues in his book How Children Succeed that culture, family environment, and preschool support are instrumental in shaping youths to become valued members of society. And important studies by Americans such as psychologists Eric Turkheimer and Richard Nisbett have produced new insights from studies of twins. These analysts searched for separated twins so that they could assess the influence of different learning environments. Turkheimer concluded that the economic status of households in which youngsters are raised can trump the impact of genetics. “The IQ of the poorest twins appeared to be almost exclusively determined by their socioeconomic status.” He concluded that the cognitive abilities of even the least advantaged children are extremely malleable.59

Nisbett reached a similar conclusion: “It is now clear that intelligence is highly modifiable by the environment.” Psychologist Ulman Lindenberger at Berlin’s Max Planck Institute for Education Research came to the same conclusion: “The proportion of genetic factors in intelligence differences depends on whether a person’s environment enables him to fulfill his genetic potential.”60

In an important conclusion, Nisbett determined “50 percent to be the maximum contribution of genetics,” with the importance of environment to cognitive ability typically more pronounced, especially among the least advantaged. The issue of nurture versus nature is a complex field. Yet such research provides evidence that the successful approach of family capitalism countries to poverty alleviation is based on sound science and could be duplicated by the United States.

The family capitalism countries behave as though childhood impoverishment is only a temporary birth defect to be remediated by support, jobs, and education. Communities amid an abundance of jobs paying livable wages are communities where hope and opportunity flourish, where cultural norms are strong, and where employed parents and neighbors provide stable role models. They are communities where families accumulate social capital and where the predicates of a good education and personal responsibility become self-evident to youths who perceive opportunity. Conservatives attribute American poverty to the many low-wage workers entering world labor markets or fault cultural norms among the poor and a breakdown of US family structures. The factors making for American poverty are varied and complex, but its origin is not too many Chinese or missing fathers, but too few American jobs paying livable wages.

The success of the family capitalism countries powerfully affirms that poverty alleviation cannot succeed in the absence of good jobs. Preschool, inexpensive child care, good quality schools, and inexpensive college are resources that families can reasonably expect from the public sector. But the single certain necessary and sufficient condition to ameliorate the pathologies, inopportunity, disrupted communities, and despair that beset impoverished Americans is a sufficient number of good jobs.