CHAPTER 17

AUSTRALIAN-STYLE WAGE DETERMINATION IN FAMILY CAPITALISM

“There is also a system of generalized regular arbitration that served for a long time as the pillar of industrial relations in New Zealand and Australia. This system originated in legislation of 1894 and 1904….”1

SABINE BLASCHKE, BERNARD KITTEL, and FRANZ TRAXLER,

National Labour Relations in International Markets, February 2001

“The real point is that humans are meant to be the object of the economic exercise. When you seek to raise productivity and material living standards by making peoples’ working lives a misery of uncertainty and insecurity, damaging people’s family lives and even their health, you confuse means with ends.”2

ROSS GITTINS,

Economics Editor, Sydney Morning Herald, July 2011

“Over the past few decades, several European nations, like Germany and the Netherlands, have played by the rules and practiced good governance. They have lived within their means, undertaken painful reforms, enhanced their competitiveness, and reinforced good values.”3

DAVID BROOKS,

New York Times, December 2, 2011

“The Netherlands has achieved what others only dream of: collective agreements without strikes, coupled with a healthy economic growth and a reduction in unemployment.”4

RUTH REICHSTEIN,

Handelsblatt, October 2010

Australian-style national wage determination is the heart of family capitalism’s ability to widely broadcast the gains from growth and attain broadly enjoyed prosperity amid globalization. The pivotal concept first emerged 120 years ago in Australia and New Zealand, and features collaboration by employees and employers to raise real wages annually. How did that happen?

The nineteenth-century roots of Australian-style wage determination were explained this way by University of Vienna sociologists Sabine Blaschke, Bernhard Kittel, and Franz Traxler in 2001:

“There is also a system of generalized regular arbitration that served for a long time as the pillar of industrial relations in New Zealand and Australia. This system originated in legislation of 1894 and 1904 that enabled the unions to make all employers party to the arbitration procedures, resulting in a binding decision on the terms of employment (i.e. the award) by special tribunals….”5

These researchers are part of a global community of scholars examining how wages are reached in the rich democracies, a community including Americans like sociologist and political scientist Lane Kenworthy at the University of Arizona.6 Reaching back well before the Hallmark 1907 Harvester decision, New Zealand and Australia established the legal foundation for laws and practices embodying a livable wage that evolved to the nationwide wage agreements common in rich democracies. This important element of family capitalism emerged perhaps independently early in the twentieth century in Denmark, later during the 1930s in France and Switzerland, and during the war years in Sweden. It was adopted as a key component of the hyper-competitive German codeterminism model introduced in the aftermath of World War II. German reformers such as Konrad Adenauer, Ludwig Erhard, and Walter Eucken were vital. But absolutely critical to its emergence was the exigency of the Cold War that justified a dramatic experiment by the Allies. The experiment included drawing on the successful experience of neighbors with Australian-style wage setting mechanisms ensuring that productivity gains are shared by both employees and employers. Employers reach wage agreements with families who are represented in negotiations by surrogates from unions in a process closely monitored by government officials.

Australian-style wage policies and northern European codeterminism, where employees and employers closely collaborate to enhance family and firm success, must appear strange indeed to Americans after a generation of Reaganomics. Yet ironically, codeterminism and the Australian wage system are drawn directly from American business practice and economic research, their roots and intellectual provenance resting firmly in American economic history. Indeed, the success of the family capitalism countries rests as much with a number of American and British visionaries and scholars as it does with their own economists and politicians, as we see now.

The Ford Model Prioritizing Productivity, with Wages Based on Value-Added

One American visionary was a wealthy Utah businessman named Marriner Eccles, Franklin Roosevelt’s chairman of the Federal Reserve System. A stout defender of legacy capital, Eccles was no socialist. He provided both the muscle and the vision during the New Deal era that gave lift to Adam Smith’s centuries-old hope for capitalism to improve the lot of all mankind:

“Mass production must be accompanied by mass consumption, and this in turn implies a distribution of wealth—not of existing wealth, but wealth produced during the same period—as it provides men purchasing power equivalent to the quantity of goods and services offered by the country’s productive apparatus.”7

The Smith/Eccles/Roosevelt recipe of family capitalism is straightforward: the moral sentiments of society should be harnessed in support of widely broadcasting the gains from productivity growth. Attaining that goal hinges on two elements from Henry Ford adopted by these countries: prioritizing productivity growth in order to maximize economic growth, and linking wages to labor productivity growth.

Prioritizing productivity reaches back to the British economist Alfred Marshall and the Austrian Joseph Schumpeter who first preached the seminal importance of raising productivity as the precursor to prosperity.8 This lesson was emphasized anew in the postwar era by a number of nations, including the family capitalism countries and Japan. Indeed, the first great challenge to America’s postwar economic preeminence was Japanese firms such as Toyota in the 1970s and 1980s. Initially mocked, the quality, consumer appeal, and pace of productivity improvements embodied in postwar Japanese products in the space of a decade or two revolutionized global manufacturing. We have learned that American management’s attention to productivity concerns waned with the introduction of Reaganomics as executive suites turned inward, pursuing the windfalls abruptly on offer. But the family capitalism countries were not sidetracked. They remained attentive to the urgency of productivity growth in order to compete with the American postwar juggernaut and the first tendrils of global integration represented by Japanese exporters.

Innovations like just-in-time inventory control were important, but the genuine Japanese revolution was a ferocious focus on quality (kaizen). In turn, that placed a premium on what has become a northern European strength in the decades since, thanks to work councils and codetermination: active intrafirm communications up and down the hierarchy chain leading a relentless search for improved productivity. Their evolved approach has emerged as the sine qua non for enterprise success in modern capitalism. And the management structure most attuned to its implementation in the postwar era has proven to be codetermination, yielding the competitive superiority the northern Europe nations enjoy today on the technology frontier.

The second tenet of family capitalism drawn from Henry Ford is to link wages to productivity growth. We learned earlier that productivity growth in the US became decoupled from wages during the Roaring Twenties and again during the Reagan era. In contrast, practices in the family capitalism countries reflect the teachings of Ford that wages should reflect something approximating employees’ marginal value to employers. Even more significant, the design of the Australian-style wage determination system practiced in these nations is a direct mimicry of the human resource policy of every American enterprise.

Family Capitalism Applies American Corporate Wage Practices

Australia and northern Europe translate rising productivity into rising wages using various permutations of a collaborative public and private mechanism, with most wages nationwide increasing by an amount each year tied to the rate of inflation plus some sizable portion of the rise in productivity. That’s the outcome of the Australian-style wage mechanism even though countries use different arrangements. That system resembles what occurred in America during the golden age where wage settlements at blue chip firms like GM became national templates for wage setting in all sorts of other enterprises.

The family capitalism system draws explicitly from American business practices at another conceptual level as well. How do these nations justify what tend to be somewhat uniform wage hikes across their economies in light of the fact that productivity growth is far from uniform between sectors like retailing or manufacturing?

It turned out to be simple. They just looked at what American firms were doing in the golden age.

In designing their wage mechanisms, officials in family capitalism countries examined how the best performing enterprises in the world at the time determined wage increases among their own employees. The officials merely mimic the behavior common to every single American office, plant, and corporation. Senior American human resource officials today from Fox News to GE and Koch Industries would instantly recognize the mechanism as their own. In American firms as we know, wage gains on average have struggled even to keep pace with inflation. Even so, whatever nominal wage increases that do occur are allocated with the most productive employees receiving rather less than their marginal product while the least productive receive rather more. Drawing on analyses by researchers like Stanford business professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, Alison Davis-Blake who is Dean of the University of Michigan business school, and Alison Konrad at the University of Western Ontario,9 Cornell economist Robert H. Frank explained in The Darwin Economy just how pervasive this distributive pattern mimicked by the family capitalism countries is within American enterprises:

“The pattern is widespread. In every occupation for which data facilitate the relevant comparisons, the most productive workers in any unit are paid substantially less than the value they contribute, while the least productive workers are paid substantially more…. That’s precisely the pattern we’d predict if people assign considerable value to high-ranked positions within work groups…. In effect, each employer administers an implicit income distribution scheme that taxes the most productive workers in each group and transfers additional pay to the least productive.”10

He specifically referred to the pay pattern in the US private business sector:

“In short, the startling fact is that private business typically transfers large amounts of income from the most productive to the least productive workers. Because labor contracts are voluntary under United States law, it would be bizarre to object that these transfers violate anyone’s rights.”

The Australian-style national wage systems of the family capitalism countries allocate the gains from growth among workers the same way that the private labor market does at Apple, Ford, Google, Microsoft, and the Wall Street Journal. They mimic the precise pattern in firms that libertarians and market fundamentalists laud as exemplars of innovation and high-performing work places. In Germany during 2012, this system produced wage gains averaging about half a point above the consumer price index, ranging from a nominal 3.3 percent in the highly productive capital goods industry to only 2 percent in the banking and insurance sectors.

Wage Determination Features Compromise—Not Conflict

The wage-setting mechanisms that have evolved in the family capitalism countries are rooted in American corporate practices, but the job site orientation is entirely different. Rather than wage compression featuring commoditized and disposable employees, these high-performing economies place a premium on job site productivity and rewarding John Calvin’s work ethic. The enterprise cultures abroad are profoundly different, with employees viewed as assets, not liabilities.

That seminal difference can best be grasped by examining the potential wage crisis confronting Germany in 2011. Workers from lower-wage Eastern Europe would be permitted unfettered access to the booming jobs market in Germany after May 1, 2011 under EU rules. Predictions were dire, with up to 800,000 moderately skilled Poles, Czechs, and others expected to flood Germany, overwhelming job markets and suppressing wages. But forecasters hadn’t counted on the character of northern European job sites after decades of globalization, where highly productive, seasoned, and skilled employees are more vital to firm success than cheap wages.

Fear quickly turned to puzzlement when the flood turned out to be a dribble; only 26,000 migrants arrived in the first three months after May 1, not markedly more than the 10,000 migrants in the preceding three months before May. And the German trade union federation DGB determined that only 67,000 came in the first six months.11 What happened? There were simply few jobs on offer for the newcomers. Explanations such as language barriers were given, but the Institute for Labour Market and Employment Research (IAB) in Nuremberg figured it out. They fingered the German labor model, which prioritizes worksite performance over wage compression: only the highly skilled need apply.12 Herbert Brucker of the IAB explained the outcome was the consequence of the explicit German rejection (because it hobbles productivity growth) of the American-style “hire-and-fire” labor model.

How are nationwide wage increases set by the family capitalist countries? Recall that we reviewed the process in Australia in Chapter 3, including this explanation from that government’s Bureau of Statistics: “In Australia, the 1983 Wage Accord established a centralized wage fixing system that took into account economic policies and the Consumer Price Index. By 1987, the replacement was a two-tier system that distributed a flat increase to all workers and made further increase provisional on improvement in efficiencies.”13

This Australian-style approach with its roots reaching back to 1894 is common in the other family capitalism countries, where economy-wide parameters for wage gains are devised and applied to the vast majority of jobs. Regional and nationwide wage and benefits agreements are negotiated by employer groups with trade union organizations, who act as agents for families, and then reviewed by governments.14 The system resembles the Nordic model mentioned earlier, with scholars Åge Johnsen at Olso University College and Jarmo Vakkuri at the University of Tampere writing that it features a high degree of consensus building, with decisions being evidenced-based rather than ideology based.15

As applied specifically in the Netherlands, Ruth Reichstein’s epigraph summarized the outcome of its Australian system this way: “The Netherlands has achieved what others only dream of: collective agreements without strikes, coupled with a healthy economic growth and a reduction in unemployment.” Emphasizing collaboration and compromise rather than conflict, and revised continually to enhance labor market flexibility, this consensus system is the heart of family capitalism.

The Australian mechanism has been modified locally in each nation. In some, wages are set locally or regionally between employees and employers with little public sector oversight, while in others—Norway and France, for instance—government input is more direct.16 Negotiators are careful to avoid settlements that significantly differ in magnitude from those in neighboring countries. As in Australia, labor federations are at the center, as representatives for all employees and their families. Government can step in should negotiations falter, a prospect that incentivizes negotiators to reach agreement on their own. Failure of employers and employees to collaborate is punished, not rewarded.

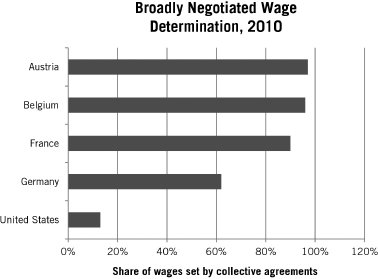

These negotiations focus on key economic variables, including profits, inflation, taxes, fees for social programs, and especially productivity. And it is common for wage settlements in one sector or region to establish benchmarks for salary settlements to a greater or lesser degree in most sectors and throughout each country. Some major industries conduct their own individual wage negotiations, but collective agreements or nationwide benchmarking covers anywhere from 62 percent of employees in Germany to 90 percent or more in neighboring nations, according to the ILO and the Berliner Zeitung.17 Chart 17.1, using statistics from the German Economic and Social Research Institute, indicates that broad wage settlements are most comprehensive in Austria and least comprehensive in America.

Chart 17.1.

Source: Economic and Social Research Institute, Berlin, October 24, 2012, and Stefan Sauer, “Collective Bargaining Coverage in Germany: Wages No Lower Limit,” Berliner Zeitung, Oct. 15, 2012, http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/wirtschaft/tarifbindung-in-deutschland-loehne-ohne-untergrenze,10808230,20706404.html.

Here is how the wage-setting mechanism in hyper-competitive Germany functions. Only larger firms such as VW-Audi-Porsche engage in direct talks with employee unions. Instead, most wages are negotiated at the state level, as in the Saarland, Hess, or Rhineland-Palatinate, between employer groups and trade federations, with the outcome setting national templates.18 In July 2011, for example, a de facto national guideline emerged from the collective agreement reached in the state of Baden-Württemberg. It provided for about 1 percent real wage gains, with retail employees receiving a 3 percent nominal wage hike (and 36 paid vacation days for some), with inflation at about 2 percent. Here is how the German Federal Statistical Office explains its regionally based process for reaching national wage determination: “The impact of collective agreements goes far beyond that. Many businesses and employers who are not bound by them nevertheless use the agreements negotiated for the relevant branches for orientation purposes.”19

As a result, most employees in each of the family capitalism countries typically receive annual wage increases comprising two components.20 The first component hews to a broad standard intended to offset the erosion of inflation on employee earnings, while the second component is intended to ensure that employees receive a portion of the gains from growth, with total wage settlements typically exceeding inflation. This second element is where the gains from growth are sliced, and negotiations are vigorous and detailed. Individual company product lines and prospects can be exhaustively examined and debated.

Employees have a stake in striving for wage increases, of course, but not at the expense of firm survival because they have long-term attachments to employers; they covet enterprise success and that moderates wage demands. For their part, keenly sensitive to the urgency of productivity growth, employers have a stake in maintaining an energetic workforce while avoiding strikes. Yet employers also prioritize flexibility to hire and fire workers, to control labor costs while meeting sudden market changes, to optimize low labor turnover, and to be profitable for their shareholders and thereby able to invest in new technology to meet competition.21 Wages do not rise beyond a cost-of-living adjustment if productivity growth is poor: “Salaries in France should be increased only if there is an increase in productivity,” is how Reuters quoted former Economic Minister and now IMF chief Christine Lagarde in March 2011.22

Here is how this system worked in France in 2006. Productivity in 2005 rose 1.8 percent—better than the United States, but only one-half that of Sweden, for example. Inflation at the retail level was about 1.6 percent. As it unfolded, average monthly gross salaries at French companies were negotiated upward by about 2.6 percent in nominal terms, yielding an increase of 1 percent in real terms.23 That means a bit more than one-half of the gains from growth from rising productivity in the previous year flowed to employees in 2006, with the rest to employers to cover investment, R&D, and other expenses, and corporate profits.

At both domestic firms and American transplants in the family capitalism countries, trade federations play a pivotal role in coalescing public opinion, modulating or accelerating wage demands, and representing employees and families in this process, even though actually union membership is low. In Australia, France, and Netherlands, for example, only a minority of employers are directly covered by trade union agreements; union membership in the Netherlands was only 21 percent in 2010, down from 28 percent in 1995. Even so, voters expect trade union negotiators to exercise broad responsibility in the annual wage talks for nonunionized citizens and families, because the outcome establishes de facto national wage raises covering almost all employees.24

Avoiding Inflationary Wage Drift

Negotiators are especially vigilant against the dangers of inflationary wage settlements. Indeed, a major purpose of a significant 1983 Australian wage accord was to end inflationary “wage drift” there that had caused firms to become internationally uncompetitive. Various European countries and Australia struggled with what economists call wage drift in the decades after World War II, when wage hikes well above productivity growth generated inflation. Inflation disincentivizes investment and sends interest rates skyward, slowing growth, reducing employment, and perhaps precipitating instability resulting in currency devaluation. Indeed, controlling wage drift was a critical element in the launch of the EU over a decade ago. The fact that national currencies such as the German mark and the French franc were being replaced with a continent-wide euro meant that wage and price decisions (and government budget decisions, as we have learned) anywhere affected employers and employees everywhere. The safety valve of currency devaluations was no longer available for individual nations.

After decades of experimentation, the northern Europe wage mechanism adopted by the EU attacks wage drift in four ways:

First, automatic indexing of wages such as the Italian Scala Mobile was sharply scaled back or abolished, replaced with more flexible annual negotiations.

Second, the process has evolved so that a portion of wages is paid as variable and flexible thirteenth-month bonuses tied to profits. Sizable bonuses are nearly universal in northern Europe and are a major component of incomes; they typically represent 10 percent or more of annual earnings for many workers. Relying heavily on variable bonuses linked to firm profitability maximizes employee wage increases while also maximizing employer flexibility to control labor costs in the future, because it moderates base wage increases. Bonuses are adjusted each year during wage talks to reflect enterprise success. The logic of this practice in northern Europe is precisely analogous to the practice on Wall Street, where financial sector bonuses fluctuate with firm success.

Third, the public sector stands ready to assist firms in moderating inflation. Occasionally, government officials will intervene directly in wage negotiations, using the lure of public benefits in order to avoid inflationary wage increases. In the past, for example, wage negotiations in the Netherlands have sometimes included government-proffered tax cuts, enabling negotiators to hold down wage hikes and thus moderate labor costs and prices.25

Fourth, perhaps the most important element in avoiding inflationary wage drift is the responsibility forced on participants by the concept of unified wage negotiations. In the early postwar period characterized by labor shortages, wage drift occurred in part because of competitive forces among employers eager for workers and also by trade unions in competition to boost wages. By imposing a higher degree of responsibility, the Australian wage mechanism changed those dynamics, greatly easing wage-push pressures. With employees assured of reasonable wage gains in the future, pressure to score excessive wage gains today is eased. The added responsibility the current system imposes on trade union and employer negotiators has had similar salutary effects on inflation in Australia.26