CHAPTER 18

GLOBALIZATION CAN BE A BOON OR A BANE

“The positive conclusions of the cross-country study of inequality were that widening income gaps were not inevitable and technology forces driving incomes apart could be successfully countered with active government policies…. Globalisation had little impact on the gap between rich and poor.”1

Editorial,

Financial Times, December 2011

“Germany has been the winner in the globalization process.”2

KENNETH ROGOFF,

Der Spiegel, February 20, 2012

“67 percent of French employees believe globalization is ‘good for employment in France.’”3

ANNE RODIER,

Le Monde, June 26, 2011

Globalization holds a potent lesson for America. But as we are learning, it isn’t the one you might anticipate: families in almost all other rich democracies benefited from the acceleration of international trade in recent decades. For that reason, future scholars are likely to view globalization as the nail in the coffin of Reaganomics.

Globalization Hit Europe Harder

Americans despise globalization. By a margin of better than 2:1, a July 2007 Financial Times/Harris poll found that Americans believe globalization has harmed, rather than helped, the US.4

But northern Europeans and Australians don’t seem to get it. A remarkable 94 percent of French employees, for example, in May 2011 considered globalization “good for the development of the company,” and 67 percent believed it’s “good for employment in France.” Americans have complex feelings toward foreigners, but few believe the French to be utterly delusional. Good for employment? Didn’t they receive Jensen’s memo about their plight, dictated by the impersonal forces of the marketplace and international wage arbitrage?

Buckle up. We’re going to learn that the story of globalization is not what happened in America, a discouraging and atypical experience which is the just the opposite of experiences in other rich democracies. The real story of globalization is what happened in Australia and northern Europe.

In America, global integration is a convicted wage killer. But we know that not all Americans suffered. Its dynamic forces improved resource allocation, greatly expanded world trade, and became a wealth machine for a thin slice of America. That meant greater rewards to owners of capital, innovators, and the most skilled, whose shares of national income rose. But for others, a race to the bottom in wages ensued, with workers in Milwaukee, Brooklyn, and Dallas competing one-on-one with workers in Sri Lanka, New Delhi, and Shanghai. And the biggest losers have been less skilled workers and high-wage union shops targeted by the offshoring and wage compression features of Reaganomics.

European economies are much more integrated and influenced by world trade than is America’s. Logically, losses and labor market churning from global integration should have been even more severe in Europe. Three-quarter of the sales of the thirty German firms listed on the blue-chip DAX stock exchange in Berlin were overseas in 2010, for example, up from 66 percent in 2006; that includes Adidas, where 95 percent, and Merck, where 86 percent, of sales were abroad.5 Even two-thirds of all sales by the giant Metro supermarket chain occur abroad, including subsidiaries Media Market and Saturn. In many European countries, the sum of exports and imports in any single year has a value not far short of total GDP. The equivalent GDP trade component for the United States is far less—around 20 percent of GDP.

Because they’re more integrated in world trade, the family capitalism countries faced a stiffer adjustment to the forces of globalization than did the United States. Indeed, the potential wage depressant and labor market effects of globalization were more than twice as harsh in France and nearly three times greater in Germany than in America. Unlike America, the economies of these nations prosper or wither by international trade. And make no mistake, many skilled jobs are lost in northern Europe due to globalization.6

The Impact of Globalization on Labor Markets

The following two tables present the detailed impact of globalization on labor markets in the United States and Europe. They’re reproduced from a 2007 econometric study, The Globalization of Labor, by IMF economists Florence Jaumotte and Irina Tytell.7 The study focused mostly on the United States and northern Europe, and the results are most applicable there, although statistics from Italy and Portugal were included. The IMF analyzed data from 1980, just as global integration accelerated, until 2003 well before the recession; it parsed the impact of globalization and technology progress on subsets of workers, divided by overall skill levels.

The analysis concluded that globalization and technology change put a premium on job skills, just as economic theory would predict. Table 3, for example, shows a rising share of labor’s overall income going to employees in occupations classified as skilled by the OECD in both America (from 39 percent to 43 percent) and in Europe amid globalization. Job prospects improved as well for such workers in the upper echelons of the labor hierarchy: employment in skilled sectors in America grew 25 percent (the index number rose to 125 from 100), while skilled-sector employment grew an even larger 57 percent in Europe.

Skilled Labor Benefits from Technology Progress and Globalization

1980 |

2003 |

|

| The share of labor income received by skilled-sector labor1 | ||

United States |

39% |

43% |

Europe2 |

38% |

41% |

| Index of skilled labor employment | ||

United States |

100% |

125% |

Europe |

100% |

157% |

Table 3.

1 Measured as share of economy-wide value added.

2 Includes: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal, and Sweden.

Source: World Economic Outlook, fig. 5.7 and 5.9, IMF, 2007.

The much greater magnitude of growth in the skilled labor category in Europe is a first surprise, the tip of the iceberg: the IMF economists determined that skilled-sector employment in Europe grew much more strongly than in America amid globalization. We will return to this evidence of European economic prowess in a moment.

Unsurprisingly, as we see in Table 4, American and European workers in relatively unskilled, labor-intensive sectors fared less well. That’s consistent with the famous conclusion reached in 1941 by Wolfgang F. Stolper and Paul Samuelson, which is the source of the received wisdom among economists that freer trade permanently harms some employees in rich democracies.8 The IMF analysts concluded that the unskilled worker share of total wages fell somewhat sharply in both America and Europe.

The Impact of Technology Progress and Globalization on Unskilled Labor

1980 |

2003 |

|

| Labor’s income share in unskilled sectors1 | ||

United States |

25% |

18% |

Europe2 |

34% |

24% |

| Index of unskilled employment | ||

United States |

100% |

121% |

Europe |

100% |

86% |

Table 4.

1 Measured as share of economy-wide value added.

2 Includes: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal, and Sweden.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, fig. 5.7 and 5.9, 2007, IMF.

For a second surprise, look at the data on the last lines of this table. While unskilled jobs rose 21 percent in America, the absolute number of unskilled employees in Europe actually declined over these decades of rapid global integration and technology change. Think of the implications of that sentence. Unlike America, the European process of adapting to globalization resulted in the elimination of unskilled, low-wage jobs, replacing them with ones in higher-skilled economic sectors. The IMF analysis reveals that European employers upskilled the domestic job mix, with good jobs supplanting unskilled ones. In contrast, American employers during the Reagan era sat on their hands, doing little to change the economy’s skill mix, with the number of skilled and unskilled jobs rising about the same.

Europe Managed Globalization by Upskilling Employees

The IMF labor force data is a big surprise. While the forces of globalization hit Europe much harder than America, the IMF found that Europe adapted by eliminating jobs in lower-skill sectors, replacing them with jobs in higher-skill ones. Jaumotte and Tytell described their significant finding this way: “In Europe … employment in unskilled sectors lost ground to employment in skilled sectors (and actually contracted by a cumulative 15 percent).”9 Did Europe really pull that rabbit out of its hat in the Reagan era? A conclusion this significant can be double-checked using data from another international agency, from OECD statistics on the job skill mix in the United States and Europe.

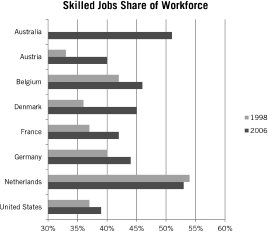

The OCED studied the skill distribution of labor forces in its 2008 edition of Education at a Glance, with statistics from the most intense period of globalization, 1998 to 2006. Their results are replicated in Chart 18.1, and confirm in detail the IMF results. The OECD found that nearly every nation in northern Europe and Scandinavia increased the proportion of its population employed in categories classified as skilled, such as managers, professionals, technicians, and associated professionals. The only exception to this upskilling was the Netherlands, where the share fell 1 percentage point; that occurred because the Dutch already had an astoundingly skilled workforce by 1998. A whopping 54 percent of its entire workforce was classified as skilled that year, the highest in the world. It’s as though Silicon Valley in its entirety was transformed into a nation called Holland and plunked down on the cold North Sea beaches between Belgium and Germany.

Australia isn’t far behind; it has the second most skilled workforce in the world and the smallest share (not shown) of unskilled employees (6 percent) aside from Norway (4 percent). The story is much different in the United States, as we see in the chart, where the proportion of Americans working in skilled jobs moved little in the Reagan era. That confirms the trend over the longer period of 1980–2003 uncovered by the IMF economists Jaumotte and Tytell.

Chart 18.1. Ages 25-64. Australian data not available for 1998 or earlier periods.

Source: Education at a Glance, table A1.6, OECD, 2008, Paris.

The OECD data also show that upskilling by Austrian and Danish employers was so dramatic that the share of skilled employees in each of their workforces leapfrogged America. And the share in France went from parity with the United States in 1998 to well above (42 percent) by 2006. Consequently, by 2006, the share of American jobs classified as skilled on the OECD global standard was lower than every nation in northern Europe, and far below Australia as well.

You have just read what should be the obituary for Reaganomics. In a world where family prosperity hinges on adapting to globalization and on upskilling to boost productivity and grow wages, it proved to be absurdly inadequate. It certainly redistributes income from families to those Adam Smith called merchants and master manufacturers. But it weakens productivity growth, and has proved to be the variant of capitalism you want your stoutest competitor to adopt.

A third major matrix of workforce skill levels during the era of globalization is the share of students with STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) backgrounds. These are folks with technical training beyond the secondary school level and their numbers indicate workforce capability and prowess vital to international competitiveness. In 2012, the OECD examined the share of STEM graduates in the labor forces of the rich democracies and determined that the share in Germany is 20 percent larger and the share in France and Australia is 50 percent larger than in the United States.10

This profile is reflected in the relative erosion of engineering students in recent decades. The United States ranked 27th out of 29 rich countries in the share of college students studying science or engineering, according to an October 2010 report from the National Academy of Sciences in Washington.11 That portends competitive problems in the years ahead for the American economy as explained this way by the OECD:

“STEM graduates are a key input to innovation. However, they represent a relatively low share of persons aged 25–34 years in employment in the United States. Moreover, below the PhD level, the share of STEM in total graduates has not increased over the past decade despite wage data pointing to persistent, and at lower qualifications levels, worsening shortages of STEM workers.”

Moreover, it seems that the quality of American technical teaching has stagnated as well, while competitors edged past: the World Economic Forum at Davos ranked the United States 48th out of 133 nations in 2010 in the quality of science and math instruction.12

What these impartial IMF, National Academies, and OECD analyses reveal is that, in an era where superior job skills are the key to future prosperity, Australia and every northern European nation has surpassed the United States to acquire a more skilled and competitive labor force. That transformation helps explain higher productivity growth rates abroad and higher wages there, too. Even more significant, Europe’s ability to supplant unskilled with skilled jobs amid globalization can’t be an accident. These data are strongly suggestive that family capitalism countries have evolved a panoply of practices to ensure that globalization enhances, rather than harms, family prosperity. The major one is codeterminism, which results in employers raising domestic skill levels and competitiveness routinely year after year. Codeterminism and other policies, such as work councils and Australian-style national wage policies, succeed in ensuring that better jobs replace those being lost to global integration, with those new jobs justifying rising real wages.

Take a breath. This is a lot of unconventional information to absorb. But the bottom line is this: America’s competitors in the rich democracies have adopted policies exploiting globalization to steadily improve family prosperity.

This rather profound outcome holds two obvious lessons for America:

First, policies such as codeterminism, an Australian wage system, work councils, and upskilling have proven effective in converting the dangers of globalization into broadly based prosperity and steadily rising wages. As the epigraph to this chapter from the Financial Times asserts, the harmful potential of global integration can be entirely ameliorated by public policies. And you have just read what those policies are.

Second, the evidence in this chapter exposes as mendacious the assertion of American market fundamentalists that US wages are being inexorably compressed by globalization. Indeed, economists at the OECD have studied the performance of the northern European countries and the US, and determined that globalization is not responsible for weak US wages or rising income disparities. “Neither rising trade nor financial openness had a significant impact on either wage inequality or employment trends,” concluded the OECD experts.13 And as just noted, journalists at the Financial Times know it, too. Recall the newspaper editorially concluded in 2011 that

“… forces driving incomes apart could be successfully countered by active government policies.”14

That conclusion is one of the most significant findings in this book. Globalization is a canard, a straw man to deflect attention and blame from the redistributive nature of Reaganomics. America’s failure to mimic the stakeholder capitalism policies of Australia, Germany, and other rich democracies accounts for wage stagnation, the plight of American families, and eroding US competitiveness. The vaporous American Dream originates in US voting booths, not the low-wage factories surrounding Shanghai, Taipei, or Mumbai.