CHAPTER 20

OFFSHORING AND THE APPLE PROBLEM

“Manufacturing in America is in serious decline, with 40,000 factory closures and more than 4 million jobs lost over the last decade.”1

Manufacturing: A Better Future for America,

Alliance for American Manufacturing, 2009

“We stood by as big American companies became global companies with no more loyalty or connection to the United States than a GPS device.”2

ROBERT REICH,

Aftershock

“The problem with that strategy is that for the past two decades we have allowed our industrial and technological base to deteriorate as talent and capital were grossly misallocated toward other sectors of the economy….”3

STEVEN PEARLSTEIN,

Washington Post, September 2010

“American companies often save on costs by finding lower wages abroad, not by enhancing the abilities of American workers.”4

TYLER COWEN,

George Mason University, August 2011

“These are the jobs that have created the Midwestern middle class for generations. Manufacturing jobs paid for college educations, including mine. They have been cut in half over the past two decades.”5

JEFFREY IMMELT,

CEO, General Electric, December 2009

Lord Uxbridge was Wellington’s deputy commander as the combined forces arrayed against Napoleon fought desperately in Belgium against the fearsome French cuirassiers and cannoneers who had conquered Europe. At a crucial stage of the battle, Uxbridge stationed himself with the cavalry. The British historian Max Hastings described what occurred next:

“Placing himself at the head of the Dutch–Belgium cavalry at Waterloo, Uxbridge ordered a charge and galloped a hundred yards toward the French line, before his aide-de-camp felt obliged to point out that no other horseman was following his dash for glory.”6

A few American firms, such as GE, are experiencing Uxbridge moments, charging ahead to open new factories at home while their fellow US multinationals look away. Offshoring occurs in all rich democracies, but its scope and the rationale for it is much different in the family capitalism countries than in the United States. American offshoring reflects the pursuit of lower wages, using cheap and docile foreign workers to replace US workers, which directly diminishes the prosperity of American families. In contrast, firms in the family capitalism countries routinely offshore production and jobs for the exact opposite reason—as a tactic to sustain their domestic economic position.

American workers take offshoring very personally. Some 77 percent of respondents to a 2006 Pew Research Center survey viewed the practice as harming, rather than helping, employees.7 And, 86 percent of respondents in an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll in 2010 agreed that off-shoring to low-wage nations was a leading cause of America’s economic problems.8 Ironically, some of these same employees likely voted for Presidents Reagan or Clinton, who supported wholesale offshoring. All four Reagan-era Presidents supported trade agreements that facilitated offshoring, assenting to vital details demanded by multinationals eager to profit by reducing the number of high-value jobs in America.

There are two recent examples. In October 2000, President Clinton signed legislation establishing permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) with China. That ended decades of uncertainty about prospective American taxes on imports from China for American firms eager to offshore high-wage jobs there. The impact of PNTR on offshoring was dramatic. Indeed, one study in December 2012 by Justin R. Pierce of the Federal Reserve System and Yale management professor Peter K. Schott attribute the loss of as many as 4 million US manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2007 to the new certainty provided by PNTR. Utilizing census data, they concluded:

“Absent the shift in US policy, US manufacturing employment would have risen nearly 10 percent between 2001 and 2007, versus an actual decline of more than 15 percent.”9

The second example is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), enacted earlier in the Clinton administration (1993). A key provision forced Mexico to guarantee that foreign investors for the first time could actually own a majority controlling interest in domestic factories. In its eagerness for the new jobs promised by NAFTA, the Mexican government overturned centuries of xenophobia. Enacted by the Clinton Administration in collaboration with Congressional Republicans, NAFTA also contained a second important caveat: any dispute with Mexican officials would automatically bring the full weight of Washington into the settlement process, overwhelming complaining local officials. A proposed third policy was a union initiative to protect the right of Mexican workers to organize independent unions, with the goal of raising local wages. The business community’s Washington men torpedoed that provision, ensuring that exporting US jobs to low-wage Mexico would remain quite profitable.

Here is how economist Robert E. Scott of the Washington-based Economic Policy Institute explained the consequences: “… NAFTA tilted the economic playing field in favor of investors, and against workers and the environment, resulting in a hemispheric ‘race to the bottom’ in wages….”10 Scott’s observation points out the most severe impact of offshoring by American firms which is wage compression. That is the first of three elements of American offshoring that we now review:

▲ Wage compression

▲ Offshoring domestic jobs

▲ The Apple Problem: production abroad for export to the United States

Wage Compression

The actual export of jobs as well as the potential for offshoring compresses wages. As Princeton economist Alan Blinder explains, the mere threat of offshoring creates an environment that depresses wages.11 It has proven to be an effective tool to coerce concessions from employees or to fend off unionization, with extortion commonly practiced even by the largest and most illustrious US firms. For example, some 40 percent of Microsoft’s employees already work abroad, yet chief executive Steve Ballmer has threatened to export even more jobs if Democratic politicians close foreign tax havens. “We’re better off taking lots of people and moving them out” of the United States, citizen of the world Ballmer asserted.12

Any obligation of industry leaders to nurture the American economy and its workers by even the most profitable and bluest of blue-chip US multinationals has been vitiated by Reaganomics. Foreign enterprises in the US practice the same wage compression behavior as Microsoft, commoditizing American employees with offshoring threats. Here is how Nissan-Renault CEO Carlos Ghosn tamped enthusiasm for higher wages among employees at the Smyrna, Tennessee plant: “We’ll be making decisions on where future growth will occur in the United States and in Mexico based on the efficiency of operations. Bringing a union into Smyrna could result in making Smyrna not competitive.”13

Offshoring Domestic Jobs

The second element of offshoring is the actual export of existing US jobs, which is the subject of much economic research. Prior to the 1980s, American firms tended to supply foreign markets from high-wage, efficient US plants. That changed after 1980 as management at multinationals pursued Reagan rents by offshoring millions of high-value manufacturing jobs to low-wage platforms, beginning in Mexico. Starting from an admittedly low base, direct foreign investment abroad by US firms soared in the early Reagan era, as explained by Handelsblatt editor Gabor Steingart in 2006:

“Capitalists left their home turf and went looking for suitable locations to invest. Direct investment abroad … rose dramatically. Global production increased a solid 100 percent between 1985 and 1995. But direct investment abroad increased by 400 percent during the same time period.”14

The pace of foreign investment and job exports accelerated after 2000. In their analysis for the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission, for example, economists Kate Bronfenbrenner and Stephanie Luce determined that the number of production operations being offshored to Mexico, China, and India in 2004 was nearly triple the number just three years earlier, in 2001. Many of these transplants fabricate goods merely being sold directly back to the United States, displacing the identical goods previously produced domestically.15 Not all studies agree.16 But the weight of evidence provided by scholarly analyses is that net US job exports have been significant and are a notable cause of the sustained deindustrialization of the US economy during the Reagan era. The evidence is powerful, because factories being closed during this period—and reopened abroad—utilized about the same number of employees. Let’s look at several of the most comprehensive studies.

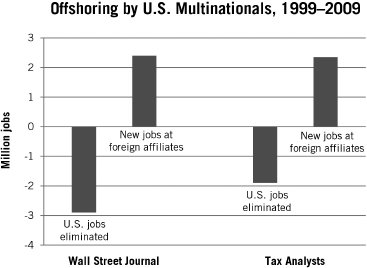

One analysis by reporter David Wessel of the Wall Street Journal in April 2011 concluded that American multinationals cut US employment by a net 2.9 million between 2000 and 2009, while expanding jobs abroad by a net 2.4 million.17 This conclusion was reaffirmed by other analyses, including one by Martin Sullivan, the former US Treasury Department economist with Washington-based Tax Analysts.18 He parsed BLS data and concluded that US multinationals eliminated 1.9 million domestic jobs between 1999 and 2008, while creating 2.35 million jobs abroad; in other words, they eliminated five American jobs for every six they created overseas, as noted in Chart 20.1.

Chart 20.1. Wall Street Journal study period 2000–2009, Tax Analysts study period 1999–2008.

Sources: Catherine Rampell, “Is a Multinational CEO the Best Jobs Czar?” New York Times, Jan. 27, 2011. David Wessel, “Big US Firms Shift Hiring Abroad,” Wall Street Journal, April 29, 2011.

Offshoring has proven to be a particular plague on the industrial Midwest. The Bronfenbrenner and Luce analysis concluded that nearly 40 percent of jobs being lost were exported from the Midwest, especially Illinois and Michigan. Offshoring has cut deeply into the industrial heart of the American workforce, with an impact broader than suggested by the bare figures from Wessel and Sullivan. It depresses wages, as Blinder noted. Many of the jobs being exported are from the unionized manufacturing sector; their high wages make them especially attractive targets for offshoring.19 Moreover, each lost job has a ripple impact on jobs at associated enterprises and suppliers. As we will see later, five or six jobs in the fabrication/supply chain are linked to each manufacturing job; those jobs are also lost when a single manufacturing job is offshored.

There is a similar multiplier impact when higher-wage jobs are exported from the technology and services sectors. Utilizing a database of 1,600 service sector firms beginning in 2004, researchers at Duke University and the Conference Board documented widespread offshoring in these sectors, too. This study also assessed the motivation for exporting jobs by these service-sector enterprises, with the authors concluding that few of the respondents pursued the strategy to enhance domestic employment.20 As in the manufacturing sector, the profits on offer from exporting high wage US jobs to low-wage platforms is the lure.

“The Apple Problem”

The third element of offshoring involves the creation of jobs at production facilities abroad intended to supply the US market with new products never fabricated domestically. This was a notable pattern detected by the Bronfenbrenner and Luce analysis. Some of the new jobs abroad support foreign sales. But millions of such foreign jobs involve fabricating for the US economy. Apple alone has nearly 700,000 employees at subcontractor Foxconn scattered across Asia, 40 percent of whom are producing goods for the American market. The consequence of such behavior by Apple and others is to hollow out the domestic industrial base. When the multiplier effects are included, the opportunity cost is far larger than measured just by the jobs figure.

The American technology jewel Apple is a poster child for this category of offshoring. Despite its products being envisaged, conceived, researched, financed, developed, and managed from America, Apple fabricates most of its products—iPhones, for example—in low-wage countries, such as China, for export to the United States. The late visionary Steve Jobs was an innovative genius, but despite agreeing under pressure in December 2012 to resume some domestic US production, his successor, Timothy D. Cook, has proven to be far from an economic patriot.

Unlike their predecessor CEOs during the golden age, Cook, Ballmer, and other citizens of the world feel little compunction to support American families. Son of an immigrant, Steve Jobs’ genius was nurtured by the schooling, opportunity, resources, and venture capital available to him in America’s Silicon Valley, a phenomenon nearly as unique in the history of mankind as the eighteenth-century Midlands. But the Americans now running his firm scarcely return the favor. About 43,000 of Apple’s 63,000 or so direct employees reside in the United States, but almost none of the 700,000 contract employees work in America.21

Multinationals like Apple should strive to locally source wherever they operate, of course. But their unwillingness to match US sales with production hollows out the American industrial and R&D base. It means less opportunity in the future for other start-ups to benefit from the same education, venture capital opportunities, and entrepreneurial outlets that were instrumental in nurturing their infancy and growth. It means fewer new Apples in the future. Leaders at most multinationals from the family capitalism countries appreciate that dynamic, as we see in the next chapter. But CEOs at Apple and Microsoft, among other companies, divert their eyes, the Reagan rents on offer trumping economic patriotism. Indeed, taking a page from the Walmart playbook, Apple treats many of its American employees poorly as well. Most of its domestic employees are in sales, and its low-wage business model induces rapid staff turnover. Some three-quarters of its retailing employees earn about $25,000 annually and work at Apple an average of only two-and-a-half years before moving on.22 While Apple has the highest profits and sales per square foot ($6,050) of any large firm in America, its hardworking employees don’t share in that bounty.23

Its low-wage strategy elicits few complaints in the United States, but has proven controversial in the family capitalism countries. Employees in Paris, for example, publicly complained in September 2012 of “remuneration considered too low, opacity in wage scales, working hours too fragmented by part-time, and a lack of perspective developments in the company,” according to Le Figaro.24 In Munich and Frankfurt, employees at Apple stores bristled at the unfamiliar imperious Apple management style and established work councils during 2012 to strengthen their hand in negotiations on issues such as work hours and vacations.25

If Apple and other American firms hire more expensive Americans, they might not even incur a profit penalty because Americans are considerably more productive. In any case, it is likely to be small, comparable to background noise for such firms. Certainly, dealing with more productive and assertive American employees requires a higher order of management skill, but that should not be a problem for firms such as Apple or Google. If the global powerhouses Siemens or VW can manage such tradeoffs, Apple can, too.

Onshoring, or bringing jobs from abroad to US soil, by firms like Apple, would be inexpensive, because labor is a small element of manufacturing costs. In the case of iPhones, for example, paying American rather than Chinese wages would add $65 or so to each unit’s cost, reported Charles Duhigg and Keith Bradsher of the New York Times.26 Put that in perspective: Apple fetched an average $427 per iPhone in 2007, but jumped its price to average $620 during the first half of 2012 as reported by Elsa Bembaron in Le Figaro, a price hike three times larger than the US employment cost differential.27 That presumably added in the neighborhood of $200 per unit to profits.

What would be the absolutely worst-case outcome if Apple hired Americans to produce for its US customers? Think of the answer this way: Apple reported profits of $41.7 billion in its fiscal year 2012. The use of tax havens (remember its Luxembourg mail drop?) kept its 2012 taxes modest, enabling the firm to increase its foreign cash hoard in the Caribbean and elsewhere to $82.6 billion at fiscal year-end. Had it used Americans to produce the 40 percent of its output sold in the United States, Apple’s foreign cash holdings under the worst-case scenario would have been $80 billion instead.28

A bit embarrassed by foreign production of goods for American customers, mendacity has come to color the business community’s justification, exemplified by this comment from one Apple executive in the winter of 2011–2012:

“We shouldn’t be criticized for using Chinese workers. The US has stopped producing people with the skills we need.”29

That would be news to Silicon Valley community colleges, nearby Stanford University, the Universities of California at San Francisco and Berkeley, San Jose State University, or the broader scientific community. If that were actually a valid explanation, all Apple need do to create hundreds of thousands of American jobs is adopt the upskilling culture of its competitors in family capitalism countries. That’s seems unlikely, however. New York Times reporters Duhigg and Bradsher seem convinced that Apple management is pivotally reliant on a docile and eminently disposable workforce always on call, living in dormitories with twelve-hour, six-day schedules.

With products now routinely shifted for fabrication abroad that were envisioned and developed in the United States, firms like Apple exacerbate—rather than ameliorate—the US trade balance. Offshoring of Apple’s iPhone, for example, contributes $1.8 billion to the bilateral American trade deficit with China.

Offshoring carries a human toll as well. Women have become as important as men in the American labor force. Yet traditionalists still view the key workforce cohort in any economy as males aged 25 to 54 years old. Back in 1954, 96 percent of them worked according to the Department of Labor. Only 80 percent were working in 2011, a difference representing over thirteen million prime-age men without jobs. Some of that erosion is cyclical, but most is not, with millions of them victimized by offshoring. Even a few conservatives fret about the problem and one or two acknowledge that government should play a role in reversing this tide. Here is David Brooks in May 2011:

“There are probably more idle men now than at any time since the Great Depression, and this time the problem is mostly structural, not cyclical…. Many will pick up habits that have a corrosive cultural influence on those around them. The country will not benefit from their potential abilities…. It can’t be solved by simply reducing the size of government….”30

Offshoring Weakens Productivity

Beyond its impact on jobs and wages, offshoring haunts America’s longer-term prospects by hobbling future productivity growth in two ways:

First, it shrinks employment in the highest productivity manufacturing sector, because those jobs are disproportionately higher-wage (frequently unionized) ones and thus prime targets for offshoring. In addition, their high wages also make them unlikely targets to be onshored.

Second, economists such as MIT’s Jerry A. Hausman have argued that the weak US productivity record also reflects offshoring of associated R&D and innovation investments that accompany the export of manufacturing jobs.31 Some of this offshoring is also a consequence of explicit, coercive industrial policy strategies abroad in some low-wage platforms. A portion of American offshoring, for example, occurs to accommodate the basest of mercantilist policies pursued by nations like China. Such nations blackmail firms eager for access to their burgeoning markets, extorting technology secrets under duress from US innovators. For example, GM was required in 2011 to reveal several innovations in its Volt plug-in hybrid in exchange for receiving the same $19,300 subsidy received by its Chinese domestic hybrid competitors like BYD’s e6 model.32 Such commercial blackmail violates rules of the World Trade Organization, to which China belongs.

Offshoring and Collapse of the Great American Jobs Machine Since 2000

Private-sector job creation has been paltry since the turn of the twenty-first century in America. The bare statistics are that fewer than 59 percent of American adults were working in 2011, compared to 64 percent in 2000.33 Offshoring broadly defined to include the Apple problem is the major reason. Indeed, virtually no private-sector jobs on a net basis were created during the halcyon days of offshoring from 1999– 2007 prior to the credit crisis and ensuing recession. Economists such as Nancy Folbre have determined that offshoring weakens the link between economic growth and domestic job creation. Using capacity at foreign affiliates, US firms can meet rising American demand with imports, without adding proportionately to domestic employment during recoveries.34 Imports have risen, not employment.

The data are informative. Prior to 2000, US companies opening or expanding domestic operations added nearly eight employees for every 100 already on the payroll. That dropped to a rate of seven during the 2001 recession. Surprisingly, it remained there during the boom period which followed before declining yet again, to a rate of six during the 2008 recession.35 And Robert Shapiro, former undersecretary of commerce for economic affairs in the Clinton administration, noted in February 2013 that private-sector job growth has averaged only 1.25 percent annually since the recovery began in 2009. That is just a fraction of the rate during the comparable recovery periods following the 1981 recession (3.7 percent) and 1990 recession (2.3 percent).36 This new dynamic obviating Okun’s Law has added greatly to the woes of attaining enduring American prosperity through the creation of high-value jobs domestically. And the solution rests largely with resolving the Apple problem.