CHAPTER 21

DOMESTIC CONTENT AND THE APPLE PROBLEM

“We can’t compete as a low-wage, low-skill nation. We have to compete as a high-wage, high-skill nation.”1

CHRIS EVANS,

Australian Minister for Tertiary Education, Skills, Jobs, and Workplace Relations, November 2010

“A new consensus has emerged in influential policy circles that the American labor market and educational system are unable to equip workers with sufficient skills … too much job turnover and too little training on the job.”2

ROBERT J. GITTER and MARKUS SCHEUER,

Rheinisch-Westfällsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (Essen) Monthly Labor Review, March 1997

“[German] Company managers set long-term policies while market pressures for short-term profits are held in check. The focus on long-term performance over short-term gain is reinforced by Germany’s stakeholder, rather than shareholder, model of capitalism….”3

HAROLD MEYERSON,

Washington Post, March 2009

President Obama cast the 2012 election in populist terms and became only the third President elected with that theme. His opponent, former Governor Mitt Romney, cast the election choice quite differently: as a decision between intrusive big government and benign small government. Voters naturally distrust big government, but key voter cohorts made clear that they also favor a government that is interested and involved in improving their lives. The 2012 election was not a referendum won by “takers” who view government largess as a birthright. It had little to do with redistribution by government and everything to do with the broader role that voters believe government should play in building a better future.

The evidence is buried deep in exit-polling data. Asian-Americans are among the most, if not the most, aspirational ethnic groups in the United States, and richer and better educated than their neighbors. They are overrepresented as small business proprietors, as entrepreneurs and in every meritocracy competition, ranging from the nation’s most selective public high schools to elite universities or as STEM graduates. They are one of the population cohorts with a vital role to play if America is to reverse what I term the Reagan decline and innovate its way to parity—or better—with muscular global competition. Republicans call them the “Party of Work.”4

They voted three to one for President Obama.

While the President’s populism had broad appeal, something else worked strongly in his favor. And we find the answer by looking at why both Asian-Americans and young voters favored his reelection. Here is how the veteran political reporter of the New York Times Sheryl Gay Stolberg explained it:

“On a central philosophical question of the day—the size and scope of the federal government—a clear majority of young people embraces President Obama’s notion that it can be a constructive force….”5

Like the fictional citizens of Tombstone, a majority of key aspirational Americans have concluded that the US government should be an ally in recapturing the frontier era combination of individualism leavened with collaborative and collective action. They hope and expect the public sector to become their ally in reversing tough family economics and dismal opportunity. It starts with good schools and expands from there to a public sector able to ensure competitive markets and that eschews favors for elite earners and corporate subsidies. They want Washington to adopt a different version of capitalism, one which rewards hard work and grit, one capable of offering a future for their children. They want America to recreate a new golden age.

Here is the way I think of it: given the choice at the polls in November 2012, Americans voted like the Danes and the Germans. They voted for a government that worries about the prosperity of families and prioritizes good jobs at home, even if that requires new policies. That means a government that thwarts deleterious market outcomes such as Red Queens, widening income disparities, or bank accounts in the Cayman Islands. And that means a government that focuses on creating good jobs despite the wishes of American multinationals. It means a government that embraces the goals of family capitalism.

Nurturing High-Value Jobs

In October 2012, the German government vetoed a merger of the French-German defense contractor EADS with the British firm BAE. The story of that veto actually began back in 1998, when the German pharmaceutical firm Hoechst merged with the French firm Rhône-Poulenc to form Aventis. Like EADS-BAE, Aventis was intended to be a merger of equals. But as events transpired, the brunt of job losses fell on Hoechst employees in Germany, especially when Aventis subsequently merged with Sanofi, another French drug firm. Fearing another sacrifice of high-value jobs to France or the United Kingdom, the 2012 defense merger was killed in Berlin.6

It is certainly true that German collaboration with France to restructure the jeopardized EU is proving productive, starting with budget constraints and a banking union. And it is also true that French, and especially German, economic success is built on strong commitments to free trade and investment, with care generally taken to avoid sheltering inefficient domestic firms. At the same time, they also take care to nurture a sturdy and secure domestic economic base. Indeed, that balancing act is common to all the family capitalism countries. For example, in the wake of the GM/Peugeot merger talks announced in early 2012, Xavier Bertrand, then French labor minister, wasted no time publicly reminding PSA Peugeot-Citroen to preserve its French employment levels.7

This domestic orientation by governments is matched by a similar commitment from corporate boards across northern Europe due to codeterminism, an institution absolutely vital to the long-term success of stakeholder capitalism. That commitment explains why offshoring in the family capitalism countries enhances—rather than erodes—family prosperity as we see momentarily. These countries have the most skilled workforces in the world and pay the world’s highest wages, because entrepreneurs, enterprises, factories, and offices in Bremen, Vienna, Cherbourg, and Amsterdam provide good jobs paying good wages. They have active industrial bases and a host of industries operating at the technology frontier, where their embrace of codeterminism, work councils, and upskilling provide a competitive edge.

And not one of them has an Apple Problem.

Codeterminism is the reason. It’s the fulcrum sustaining a domestic content perspective in enterprise board rooms. Northern Europe avoids the Apple Problem because codeterminism encourages firms to behave as economic patriots. This creates a soft de facto domestic content imperative that envelops many if not all board deliberations. That perspective means more jobs at home, with firms such as VW-Audi-Porsche passing up offshoring opportunities to keep Wolfsburg bustling and rich. And, codeterminism prevents short-termism and management rent-seeking.

Voter and consumer expectations are important in sustaining this domestic orientation by enterprise management. Families and public policies tend to nurture stakeholder capitalism by prioritizing domestic products over those from low-wage competitors or firms practicing wage compression. The collapse of Walmart in Germany is instructive in that regard, as is the current Franco-German focus on crafting meaningful standards and enforcing strictures against products inappropriately claiming EU origin. This latter theme was echoed recently by the industrialist Lakshmi Mittal, CEO and board chairman of the Luxembourg-based steel giant ArcelorMittal, who urged a “buy European” program when interviewed by the Financial Times in May 2012:

“We need measures to encourage more purchases of European goods both to boost demand and to ensure any benefits are felt by European industry rather than leading to more imports.”8

Consumers are sensitive to the broader values promoted by domestically produced goods, as indicated by data from France, where nine of the top sell ten cars in 2010 were French brands.9 Price points are important, but Le Figaro journalist Isabelle de Foucaud notes survey data showing that 49 percent of French consumers are willing to pay more for local products.10 A separate poll in October 2012 found that 50.5 percent of respondents were willing to pay 10 percent or more for Christmas gifts made in France, and a few were willing to pay as much as a 40 percent premium.11 Websites helping identify domestic products have proliferated. And some 90 percent of respondents to a poll by the French National Association of Food Industries in April 2012 favored creation of “made-in-France” product labeling.12 Reporter Charlotte Haunhorst of Der Spiegel explained that firms naturally react to consumer attitudes reflected in such polls:

“Of course, industry representatives know that a label that says ‘made with ingredients from China’ isn’t exactly good for sales.”13

The Theoretical Foundation for Domestic Sourcing

There’s a belief rooted in the nineteenth-century work of David Ricardo that expanding international trade benefits all, eventually even those initially suffering wage and job loss. Yet recall from an earlier discussion that economists have known that to be false since at least 1941, when Wolfgang F. Stolper and Paul Samuelson’s famous research appeared in the Review of Economic Studies. They didn’t just acknowledge that some will lose from international trade; they concluded that some losses will be substantial and persevere for the long term. Worse, ex post attempts to redistribute income from winners to losers are problematic; there is no happy ending for all, one of the disheartening, enduring truths of capitalism.14 Economist Rodrik explained the Stolper-Samuelson redistributive conundrum this way:

“Advocates who claim that trade has huge benefits, but only modest distributional impacts either do not understand how trade really works, or have to jump through all kinds of hoops to make their argument halfway coherent…. It is not just that some win and others lose when tariffs are removed. It is also that the size of the redistribution swamps the ‘net’ gain. This is a generic consequence of trade policy under realistic circumstances.”15

This 1941 explanation of the downside to free trade had little relevance at first in the postwar golden age of an America whose currency and multinationals dominated global trade. That was the era where paternalistic business leaders led families to conclude erroneously that broad prosperity was America’s default setting. In those wondrous decades, a rising tide of trade and incomes did in fact lift most boats.

That outcome eroded quickly in the 1980s, however, as we have learned, when Washington endorsed offshoring and the other elements of Reaganomics. Washington paid little heed as US wages stagnated and fell, but economists and leaders in the family capitalism countries had been wrestling with the Stolpher-Samuelson conundrum for decades by then, anxious to continue domestic wage growth and job creation tied to world trade. In the end, they rejected trade controls and restraints, and instead relied primarily on codeterminism and its soft domestic content element to ensure that domestic economic health is a priority concern of all employers.

Importantly, codeterminism enabled the family capitalism countries to become ferocious advocates of free trade, and firm adherents to international trade rules. Those rules provide considerable flexibility and maneuvering room for nations to custom-design variants of capitalism. Rodrik explains:

“Democracies have the right to protect their social arrangements, and when this right clashes with the requirements of the global economy, it is the latter that should give way.”16

Those requirements give way in two meaningful ways in northern Europe:

First, private internal corporate deliberations in a codeterminism setting favoring domestic employment and production are beyond the reach of international trade law.

Second, voters expect public sectors in France, Germany, and elsewhere in northern Europe to be inhospitable to foreign investment involving the leveraged buyouts of larger domestic employers. Officials are well aware of the LBO business model and history in which jobs and assets of target firms are too often stripped in order for buyers to seize short-term productivity and profits before the enterprise is resold. Some LBO targets subsequently prosper, but the business model is centered on short-termism that frequently yields outcomes antithetical to the long-term prosperity goals of stakeholder capitalism.

The Family Capitalism Countries Oppose Barriers to International Trade

Regarding government trade restrictions on imports, the family capitalism countries are the globe’s leading traders. That gives them an obvious incentive to nurture free trade and to police foreign mercantilist practices. In 2012, for example, countries threatened reciprocal retaliation if equal access for EU exporters to public procurement by the Chinese, American, and Japanese governments continued to be thwarted.17

This and occasional similar controversies have given rise to the incendiary notion of a protectionist Europe, an absurd libel against nations whose foreign trade sectors are two, three, or even four times larger as a share of GDP than the United States. Indeed, they’re stout advocates of globalization, free trade, the World Trade Organization, and multilateralism. And they should be, because they are big winners from globalization. Here is German Chancellor Merkel in June 2008: “We are witnessing an exponential increase in the penetration of globalisation. There is a protectionist temptation. This is not the right way to address the challenge of globalisation.”18 Northern Europe has displayed great tolerance in the face of invidious mercantilist practices of nations such as China. In fact, they have been too tolerant. After all, laws in the family capitalism countries delineate workplace practices, including safety, wages, and hours of work. Yet international trade features imported goods sometimes produced in exploitative conditions by Chinese and other firms such as Apple that violate such standards. Indeed, foreign firms can seize a competitive advantage over firms in the rich democracies, not from more efficiency, advanced technology, superior products, or R&D, but merely by exploiting their own nation’s lack of worksite conditions or livable wages.

Why should any rich democracy tolerate foreign firms reliant on prohibited practices seizing a competitive advantage and entering their markets through a back door? During the Reagan era, a handful of American economists argued the merits of penalizing such tactics, imposing compensatory taxes on foreign enterprises that seized advantage in this fashion. They included Jeff Faux at the Economic Policy Institute; Robert Kuttner, co-editor of Prospect Magazine; Clyde Prestowitz at the Economic Strategy Institute; and Joseph Stiglitz. But most economists, like Alan Blinder and Paul Krugman at Princeton, or Harvard President emeritus and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, were free-trade advocates.

Yet these prominent US free traders did what good economists do when confronted with convincing new data: they changed their minds in the face of surging Chinese goods, mercantilist policies such as the persistent undervaluation of the Chinese currency, the yuan, expansive offshoring, and wage erosion. It wasn’t just the impact of trade, which directly accounts for maybe 15 percent of American wage declines, or the magnitude of offshoring. Instead, it was the combined impact of offshoring, deindustrialization, Us versus Them and all the rest, plus technology change, which intensified the impact of trade on wages and deindustrialization.

Alan Blinder, for example, concluded that even good jobs in “safe” domestic service sectors (health care, education, and finance) are jeopardized by global integration and the threat of offshoring. He determined that the number of sectors at risk is two to three times larger than the number of manufacturing jobs subject to offshoring—and that the danger is growing.19

Krugman’s conversion occurred in 2007; global integration was exacerbating income disparities and “fears that low-wage competition is driving down US wages have a real basis in both theory and fact,” he concluded.20 And Summers grew concerned with multinationals behaving like “stateless elites whose allegiance is to global economic success and their own prosperity rather than the interest of the nation where they are headquartered…. Such firms are disinterested in the quality of the workforce and infrastructure in their home country.”21 He urged international labor standards to stem a race to the bottom in labor market regulations.

This sea change in mainstream economic thinking brought perceptive, hardnosed American realists into compatibility with conclusions reached years earlier by the bow wave of prescient colleagues such as Stiglitz, and by officials in the family capitalism countries. Like them, American economists support international trade; none wants to reverse globalization. The riches are undeniable. Their goal rather is to corral and render globalization compatible with broadly enjoyed prosperity.

American economists critical of Reaganomics or offshoring, however, have little influence in the pecuniary US political arena. And so trade policy remains ad hockery writ large, relying too much on temporary solutions forged at the behest of influential political donors rather than consistent, long-term planning.

Offshoring in Family Capitalism Strengthens Domestic Employment

Firms in Germany and in other family capitalism countries routinely offshore, but their motivation for such foreign investment is different than American multinationals, as captured in these comments by Horst Mundt, head of the International Department at the German trade union IG Metall. Speaking in October 2009 regarding a new plant being offshored by BMW to low-wage South Carolina, Mundt explained:

“The success of German carmakers depends on the ability to sell cars abroad. We cannot expect all the cars to be made in Germany…. The affected plant got other models to work on and other jobs—so no one was losing.”22

Motivated by an eagerness to strengthen the domestic employment base, enterprises in northern Europe do not offshore with the same vigor as American firms. Journalists at the Economist examined offshoring in some detail in January 2013, concluding that “European firms had been off-shoring less in the first place,” than American firms in recent decades:

“Cultural factors are partly responsible; Germany’s mittelstand or mid-sized family firms, for instance, sell their products globally but are more inclined to make things in their own backyards.”23

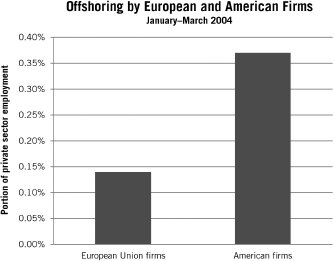

Perhaps the most thorough studies of offshoring in the family capitalism countries and Reagan-era America have been done by Bronfenbrenner and Luce. Drawing on their data, Jacob Funk Kirkegaard with the Washington-based Institute for International Economics determined that offshoring is considerably less prevalent among European firms than American ones. His results are reproduced in Chart 21.1. Kirkegaard concluded that firms from the EU 25 offshored only about one-third the jobs as a share of domestic private employment as the share exported by American firms during the same first quarter of 2004.* An even more exaggerated difference was found in statistics and projections gathered by the consulting firm Forrester Research beginning in 2002.24

Chart 21.1. Announced or reported job exports. EU 25 includes Norway and Switzerland.

Sources: Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, “Outsourcing and Offshoring: Pushing the European Model Over the Hill, Rather than Off the Cliff,” Washington, DC, Institute for International Economics, March 2005. Kate Bronfenbrenner and Stephanie Luce, “The Changing Nature of Corporate Global Restructuring: The Impact of Production Shifts on Jobs in the US, China and Around the Globe,” U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, Oct. 14, 2004.

Unlike America, offshoring in northern Europe is accompanied by domestic job growth by the same multinationals. Presumably their offshoring reduces the enterprise-wide cost profile, helping sustain investments in new employment, factories, and R&D back home. In France, during the boom period 2002–2005, for example, data from the French statistical agency Insee show that 12 percent of French firms with more than 20 employees offshored some production, averaging 36,000 jobs created abroad yearly during the study period. That isn’t surprising. French firms vie with German ones as the world’s second largest international investor abroad after the United States. But the motivation for this French offshoring is revealed by the fact that the firms involved expanded domestic operations simultaneously, creating 41,000 new jobs yearly at home over the same period.25 That is a dramatic contrast with the conclusions of the American offshoring studies reviewed earlier.

The Economist magazine suggests that this pattern is not universal, with the very largest French firms belonging to the CAC-40 Paris exchange exporting jobs on a net basis during the financial crisis years of 2008–2010.26 Even so, research by economists Lionel Fontagné and Farid Toubal concluded that, as a group, all French multinationals are net domestic job creators. Moreover, the French multinationals investing abroad simultaneously created more new jobs at home than did other French firms that didn’t offshore at all; three years after their study began, French firms investing abroad were employing an average of 25 percent more French staff at home than firms that stayed put.27 The only exception was those French firms that invested in poor countries such as Vietnam. Even French firms investing in the middle-income countries of Brazil, India, or China netted new jobs back home.

German firms also utilize offshoring to support domestic operations. Powerful evidence is the fact that some 42 percent of all jobs at firms on the Berlin DAX 30 stock exchange are in Germany, even though only 25 percent of sales come from Germany.28 The German business model is the precise opposite of Apple. Scholarly analyses support this conclusion. Martin Falk with the Centre for European Economic Research in Mannheim and Bertrand Koebel at the Otto-von-Guericke University in Magdeburg determined in 2002 that offshoring did not supplant domestic employment in the key German manufacturing sector.29

In a data-rich 2004 study, economist Dalia Marin at the University of Munich found that efficiencies realized by offshoring, especially lower labor costs abroad, led to an increase in domestic employment by both Austrian and German firms. Marin’s extensive analysis examined 1,200 projects representing 80 percent of all German offshoring in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and 100 percent of such CEE investments by Austrian firms from 1998 to 2000. This study included investments in former Soviet republics, such as the Ukraine, where wages were only 5 percent of German wages at the time, and investments in higher-wage nations including the Baltic States, Poland, and Slovenia. Marin concluded that such offshoring specifically produced net job growth in Germany:

“Lower costs of Eastern European affiliates help firms to lower overall production costs and to stay competitive…. The estimated employment demand functions show that a 10 percent decline in affiliate wages in CEE countries leads to a 1.6 percent increase, rather than decline, in the parent company’s employment demand in both Austria and Germany. These estimates suggest that the outsourcing activity of German and Austrian firms to the accession countries has actually helped to create jobs in Austria and Germany.”30

These data and analyses provide the weight of evidence supporting the conclusion that the priority of Austrian and German corporate boards is to sustain domestic prosperity. Another indicator may be the issue identified earlier, when the final opening of the European labor market in 2012 caused little employment or wage dislocation in Germany. The extraordinarily high-skill level of the northern European workforce causes employers there to prioritize applicant job skills over low wages. Indeed, the US consulting firm Ernst & Young examined the behavior over five years of 360 small- and medium-sized German firms (SMEs) during the 2000s. It determined that offshoring had dwindled since 2005 because of the sharp drop-off in labor skills available abroad. Analyst Peter Englisch noted that firms had found it

“… difficult to find the skilled labor, particularly in Eastern Europe, which—with China—has become the prime production area of German industrialists. The best candidates have been recruited by the firms that settled earlier. Instead of venturing outside the borders, SMEs prefer to consolidate their positions in Germany.”31

Several threads in this narrative are brought together in the next chapter assessing in more detail the economic prowess of the family capitalism countries, starting with their robust productivity performance.