CHAPTER 25

DELAYED AMERICAN RETIREMENT

“The number of those working past 65 is at a record high.”1

FLOYD NORRIS

New York Times, May 2012

“I’ll probably be working for the rest of my life. Some golden years.’’2

American JEAN CELINE, 64,

Starting a new job, September 2008

“Regardless of how much you throw 401(k) advertising, pension cuts, financial education, and tax breaks at Americans, the retirement system simply defies human behavior. Basing a system on people’s voluntarily saving for 40 years and evaluating the relevant information for sound investment choices is like asking the family pet to dance on two legs.”3

TERESA GHILARDUCCI,

New School of Social Research, July 2012

Teresa Ghilarducci, a prominent American researcher on retiree economics, was blunt in this February 2013 assessment:

“This is the first time that Americans are going to be relatively worse off than their parents or grandparents in old age.”4

The prospect of a lengthy and a comfortable retirement is an important quality of life issue. Like other elements of the American Dream, that promise has become ephemeral for most. The Reagan decline has diminished the prospects of realizing the presumptive American birthright of retiring at age 65 or 67. The reasons are weak wage growth, low savings, a weak private pension system, family wealth stagnation, and Social Security benefits set near the poverty level. Three-quarters of men and women close to retirement have less than $30,000 in their retirement accounts, and 28 percent of actual retirees have no savings of any kind.5

A major factor is that the private pension system prioritizes financial sector profits and reduced employer costs rather than retirement security for employees; it is mostly a commercially sponsored, voluntary, and self-directed system, each characteristic posing high danger for families. In too many instances, it forces families to go mano a mano with front-running investment firms, as explained by economist Ghilarducci at the New School for Social Research in New York:

“It is now more than 30 years since the 401(k) Individual Retirement Account model appeared on the scene…. It has failed because it expects individuals without investment expertise to reap the same results as professional investors and money managers. What results would you expect if you were asked to pull your own teeth or do your own electrical wiring?”6

The profit-motivated private system is skewed against those most in need. While 76 percent of white-collar employees enjoy private pension plans at work, over half of employees earning $27,000 or less lack access to any pension plan at work, their golden years destined to be spent working under the golden arches of McDonald’s or living in penury.7 These employees are more likely to work part time or have a broken work history, with absences that prevent steady participation in whatever pension programs might have existed at their various jobs. Moreover, they are the workers most prone to be among the 42 percent of all employees who cash out retirement funds when changing jobs, a grim augury for their retirement.

The retirement prospects of most Americans have been sharply reduced by the seminal shift of employers during the Reagan decline away from sponsoring defined benefit plans for their employees to defined contribution plans. The latter plans are far cheaper for the business community, enabling them to dodge the financial risk of providing a steady income stream to retired employees. Instead, that financial risk has been shifted to employees left to fend for themselves to find a reasonable return on retirement savings over a span of decades in competition with Wall Street professionals. Many have turned to those same professionals to manage (401)k and IRA accounts, providing plentiful profit opportunities for the financial sector.

Far worse from a national perspective, as elaborated by Michael Clowes in The Money Flood, the abandonment of defined benefit plans is a major factor promoting short-termism among money managers, pension funds, and stock market investors that exacerbates the Randian short-termism of executives.

The Reagan decline has been a perfect storm for older Americans. Led by Alicia Munnell, the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College projects post-retirement incomes in assessing how many senior are likely to fall well short of pre-retirement living standards. Since 1983, the share of retirement households likely to fall at least ten percent shy of previous living standards has jumped by two-thirds. In 2010 for the first time, more than half (53 percent) of all such American households face significantly reduced livings standards as pensioners.8 Their reaction has been to delay retirement.

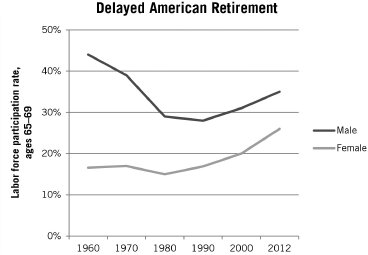

There are a number of charts in this narrative, but the next one perhaps most eloquently summarizes the consequences for most Americans of the Reagan decline. As depicted in Chart 25.1, labor force participation rates for both men and women age 65 to 69 ceased dropping early in the Reagan era, and reversed course thereafter. Now nearly one in every three seniors works, competing for jobs with their grandchildren. This rise in delayed retirements is quite a contrast to the experience of our parents or grandparents during the golden age, particularly men. Rising real wages back then enabled them to substitute leisure for labor like northern Europeans now, a happy phenomenon which caused the annual work effort of Americans to decline to about 1,800 hours, where it has been stuck ever since.

Chart 25.1.

Sources: Floyd Norris, “The Number of Those Working Past 65 Is at a Record High,” New York Times, May 12, 2012. “Labor Force Participation Rates of Persons 50 years and Over by Age, Sex, and Race, 1950-1990,” table 4–2, US Bureau of Census, Washington.

Although from a very low base, the number of seniors working increased eleven times faster than overall employment from 1999 to 2008. And the actual number of working seniors over age 65 has doubled since 1999, their share of the workforce rising disproportionately.9 These are not just part-time jobs being taken to top-off pensions. In 2007, 56 percent of working men age 65 and older were doing so full time, up from 46 percent in 1999.10 And it not just the young seniors; some 11 percent of American men over age 75 were working in April 2012.11

Eager for work, responsible, experienced, and gaudily flashing their Medicare cards, seniors work cheaply and outcompete others for jobs. That is why, since 2009, the number of senior males working has remarkably exceeded the number of teenage workers.12 For millions of senior citizens, that outcome is captured in the epigraph to this chapter by disgruntled former retiree Jean Celine as the recession unfolded in 2008. In dismay, Celine, then 64, was forced to reenter the workforce and hope that good health would enable her to continue participating for many years. “Some golden years,” she summarized, her secure retirement perhaps undermined repeatedly by her own votes since the 1980s.13

Early Retirement in Northern Europe

The situation is more optimistic in family capitalism countries where retirement ages have fallen steadily in recent decades, quite a change since the early postwar years. In France, for example, 70 percent of men between the ages of 60 and 64 worked in 1970, but only 19 percent do now.14 Moreover, while the sluggish European economy and government policies to discourage early retirement have reversed these trends to some degree in recent years, both men and women in northern Europe still retire years sooner than Americans. This pattern reflects solid public pension systems, along with decades of steadily rising real wages and the robust personal savings they fund. For example, families in Australia and northern Europe saved 12 to 15 percent or so of their incomes for decades to supplant pensions, well above paltry American savings rates.15

Only a small minority of men, and especially women, worked past age 60 there in 2006 as depicted in Table 8, even though they are denied full pension or Social Security benefits until age 65 or 67, as in the United States. Indeed, the share of American men continuing to work beyond age 60 (59 percent) was nearly three times higher than in France that year. In addition, five out of six French women retired early, by age 60, while little better than one-half of American women chose (or could afford) to stop working before age 65. These trends are starker for older cohorts. Between ages 65–69, the share of American men working in these traditional retirement years was over eight times greater than Frenchmen, and nearly four times greater than in Germany.

Early Ret rement in Northern Europe and U.S.

Labor Force Participation Rates, 2006

Men |

Women |

|||||

| Ages | 25-54 |

60-64 |

65-69 |

25-54 |

60-64 |

65-69 |

| Austria | 93% |

22% |

10% |

81% |

10% |

5% |

| Belgium | 92% |

21% |

7% |

77% |

11% |

2% |

| France | 94% |

19% |

4% |

81% |

17% |

2% |

| Germany | 94% |

43% |

9% |

80% |

25% |

5% |

| Netherlands | 92% |

34% |

14% |

78% |

20% |

5% |

| United States | 91% |

59% |

34% |

76% |

47% |

24% |

Table 8.

Source: “Labor Force Statistics by Sex and Age,” Employment Outlook 2007, Statistical Annex table C, OECD, Paris.

Unfortunately for American women, Reaganomics has proven to be an equal opportunity blight: nearly one in four American women between the ages of 65 and 69 continued to work. Unlike Ms. Celine, only a few European women toil past age 65.

Northern European governments are moving aggressively to ensure a secure public retirement system. German reforms, for example, succeeded in reversing the trend toward unduly early retirement. Though still low, the share of German women and men aged 60–64 working in 2009 was nearly double their share a decade earlier.16 And France, like the United States and Germany, has increased the threshold age for full retirement benefits for most to age 67 from age 65, and the early retirement threshold to age 62 from 60. The Hollande government last year allowed a few quite limited exceptions to those tougher standards (for those who began working careers as teenagers and the like). These reforms have worked. In combination with earlier pension reforms (1993, 2003), the net impact is projected by the French statistical agency Insee to increase the workforce there by two million employees by 2030.17