2 Sheng

Sage lifted her head and then set it down again. She was curled up in a little hollow on a hillside. She was hungry, but she didn’t feel like looking for food.

Since she’d been sent away from the pack, the moon had shrunk from a full circle to a sliver, then grown full again. She’d wandered the hills alone. She’d eaten whatever scraps she could find.

Now she didn’t even feel like doing that.

“Nobody cares if I’m alive,” she woofed aloud.

“Mopey, miserable mutt,” someone said from behind her. She heard a squawk and a whistle. Then something pulled her tail. She yelped and turned to look. No one was there.

She stood and turned the other way. She didn’t see anything there, either.

“Hey!” Sage barked.

The something poked her on her shoulder. Then it nipped her tail. It jabbed her back left paw. Sage chased her tail around and around until she didn’t know which end of her was the back and which was the front.

She ran out of the hollow.

A bird landed in front of her. It was smaller than a hawk or vulture, more like the size of a dove. But it had a sleek, dome-shaped head and a short, hooked beak. It was drenched in as many colors as Sage knew there were in the world.

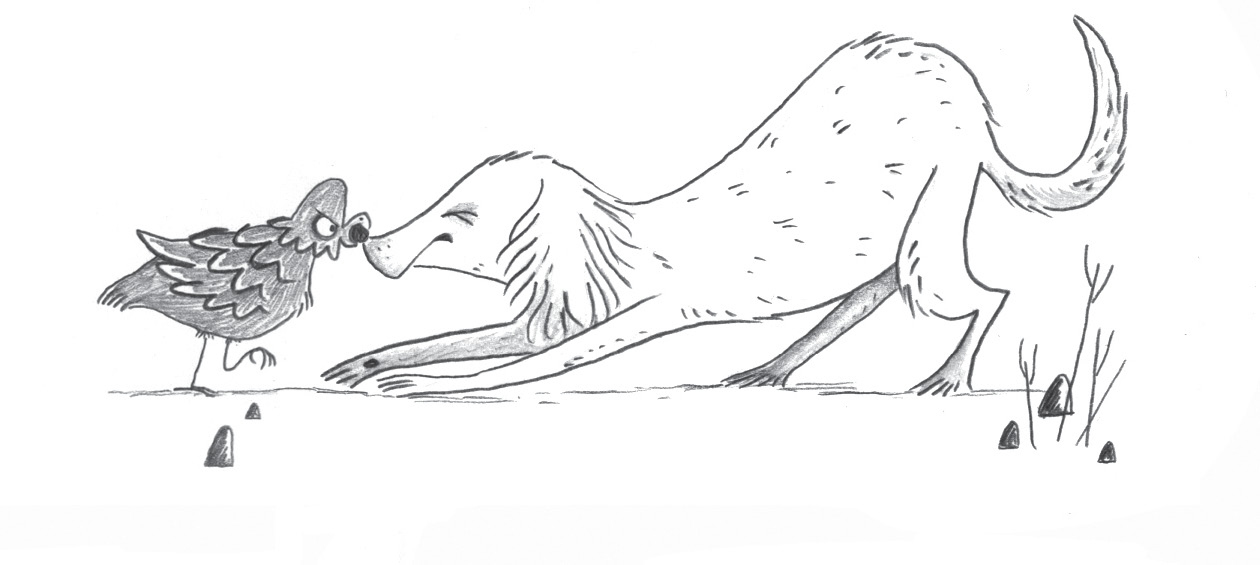

She sniffed it. It bit her nose.

“Stop that!” Sage yelped.

“Not until you come with me,” the bird said.

“No,” said Sage. “Leave me alone.”

“Stubborn, silly, sad-faced dog,” the bird trilled. “I’ve been watching you.”

The strange bird took flight. He flapped his wings around Sage’s ears. He beat at her head until she ran down the hill and across a grassy stretch of land. He chased her toward a stream. Sage jumped over some rocks and splashed on her belly in the water.

“Stubborn, silly, soggy dog,” the bird whistled. “We’re here. Look.”

There was a boy standing in the stream near a big buckeye tree. He wore loose trousers, a loose shirt, and a straw hat with a curved brim. A rope of hair trailed down his back.

He was trying to move a big rock from the bottom of the stream with a shovel. He frowned with concentration. His shoulders were bent. It looked like he was carrying a large, invisible weight on his back. He moved awkwardly, like a half-grown puppy.

“He’s big for his age,” the bird said. “His father and uncle need him to help as much as he can, but he’s only a chick. The only one for miles and miles around. I’ve flown as far as I can to look for another one. His name is Sheng and he’s ten years old. He comes from a place far away from here called China.”

He flew to the boy named Sheng and landed on his hat. The boy didn’t look up.

“Stop that, Choi Hung,” Sheng said to the bird. “There could be gold under this rock. I just have to get to it. We have to get as much as we can.”

“Brought a dog!” Choi Hung said to Sheng in human words. “Brought a dog!”

Sage had never heard an animal speak like humans spoke!

Sheng looked and saw Sage flopped there in the water. He put his shovel down on the bank of the stream. Sage got to her paws. Sage and the boy watched each other for a moment. Then, very slowly, Sheng raised his hand. Sage tensed her legs. Was he going to throw something at her to make her leave?

Choi Hung flew back to her. He poked Sage on the head.

“Don’t keep doing that!” she barked.

“Cowardly, cowering, craven dog!” Choi Hung responded. “You need a friend. He needs a friend. All he thinks about is trying to find enough gold for his family. Go! ”

Sage took a step toward the boy. He held out his hand, like a paw. She took another step. And another.

When they were close enough to touch, she sniffed his hand. Then she licked it. He tasted like stream water.

“Hello, girl,” he said.

It had been a long time since anyone had spoken kindly to Sage. She wagged her tail weakly.

She looked down at the rock in the streambed. Sheng needed help. She pushed at the rock with her front paws.

Sheng grinned. He picked up his shovel and slid it under the rock. Together, they worked it loose.

Sheng turned the rock over. “No gold,” he said. His shoulders slumped. He dropped his shovel on the rocks. “But thank you for helping.” He ruffled Sage’s ears.

“You know, most of my family is gone,” he said. “It’s just Father and Uncle and me. Most of my friends back home are gone too.” He wiped his sleeve over his eyes, but he didn’t cry.

“You look like you’re all by yourself,” he said. “Do you feel lonely and sad too? Maybe you could stay with us. You’re the color of gold! You could be Bo-Bo—a little treasure. I bet you’ll bring us luck!”

Sage almost shook with hope. I’ll be tough enough this time, she told herself. I won’t be too soft.

Sheng lived with his father and Uncle Gwan in a tent just up the hill from the stream.

“Can Bo-Bo stay, Father?” he asked. “I named her after treasure! She can help us find gold!”

Father looked down at her. His eyes were tired. But he smiled. Sage liked the way his braid of dark hair swung over his shoulder in front of his shirt and the way his face crinkled at her.

“I think,” said Father, “a boy should have a dog. Dogs make good friends.”

“Good friends!” Choi Hung repeated. “Good friends!”

Sage, who was now Bo-Bo, wagged her tail to show him how eager she was to do her part. Sheng’s father gave her a handful of warm rice. She gulped it down. A shudder of happiness went through her whole body. Her lonely days wandering over endless hills were over. She would never let anything send her back to that life again.