Word had spread across the ocean to China, too. It reached Sheng’s father and uncle in a place called the Pearl River Delta. They had spent everything they had to take a ship to California.

“But why would they leave?” Bo-Bo had asked Choi Hung the first night she’d spent with the family. She couldn’t understand why anyone would leave home if they didn’t have to.

“There was something called war,” Choi Hung had trilled. “It meant that people came to their village and tried to hurt them. And then there was something called famine. That meant there wasn’t enough food to eat. That’s why Sheng’s flock is so small now. After that, people left. Some of them heard there was a place called Gum San, Gold Mountain. They said there was gold just lying on the ground. That if you weren’t careful, you’d trip over it! And that if you waded into the water, your shoes would fill up with gold!”

But it wasn’t true. Sheng’s family had found a few flakes of gold in a part of the stream where no one else was looking for it. They marked it as their claim. That meant that it was their place to look for gold and no one else was allowed to. They worked and worked. But they had to spend half of what they found just on food and supplies. A shovel cost as much as a stove did back home. An egg was as much as a week’s worth of food anywhere else.

They couldn’t save the other half because of the Foreign Miner’s Tax.

Every month Chinese miners had to pay an extra three dollars to Mr. Smeets, the tax collector. If they didn’t, Mr. Smeets would take their claim. They would have nowhere to go. They would starve just like they would have back home.

“But that’s not fair!” Bo-Bo had barked to Choi Hung the first time she’d heard of the tax. “Why do they have to pay and other miners don’t?”

“Mr. Smeets doesn’t care about fair,” Choi Hung had answered. “He cares about making money.” The bird shook his tail feathers. “He gets some money from the tax. But he gets even more selling the claim if they don’t pay.”

The tax was due tomorrow, and Bo-Bo didn’t know if they had enough. Sheng looked worried. He swished the water faster and faster in the pan. His brow furrowed as he searched for sparkles.

Bo-Bo ran back to the stream and brought another rock to Uncle Gwan. She set it down beside him.

“You’re making me dizzy, running back and forth,” Choi Hung complained.

“Then don’t watch!” Bo-Bo barked at him.

Choi Hung had lived with the captain of the ship that Sheng’s family took on the long trip from China. Uncle Gwan had given the ship’s captain his best hat and some salted fish and taken Choi Hung with him. Choi Hung liked California better than the ship. He got seasick.

Uncle Gwan broke open the stone with a hammer. Bo-Bo panted, hoping he’d find something.

“Bad luck, girl,” Uncle Gwan said. “No gold.”

Bo-Bo pawed through the pieces of rock, hoping Uncle Gwan was wrong.

She heard a branch snap.

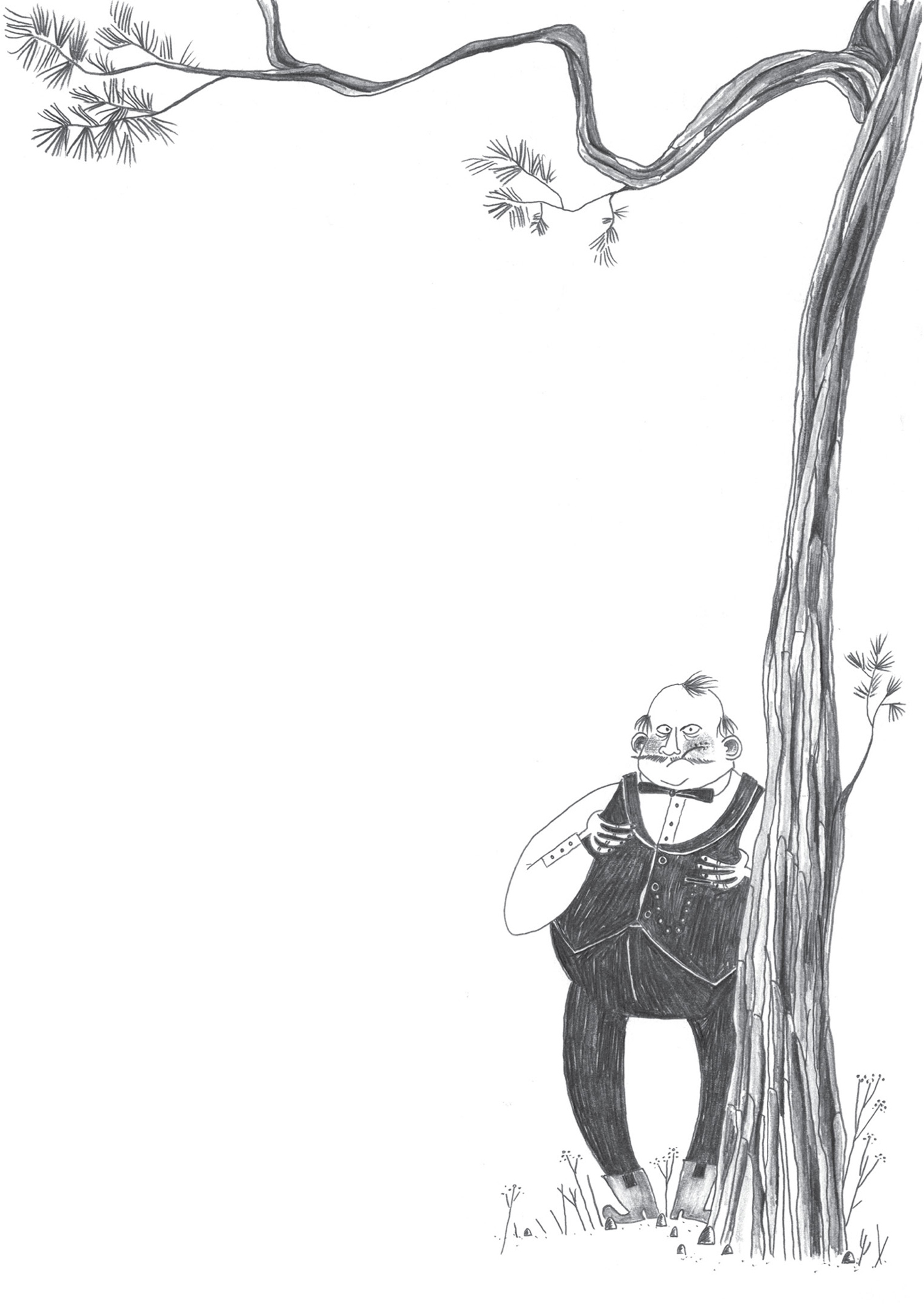

She woofed. Everyone looked up just as a man stepped out from the trees. He was short and stocky and had a scraggly mustache. He smelled like he wanted something he shouldn’t have.

It was Mr. Smeets.