December

Bear Lake: Contemplating Rhythms

In this month of the year’s shortest days, I turn to Bear Lake as the iconic destination of Rocky Mountain National Park. The car thermometer reads –6°F when I arrive at the Bear Lake parking lot, although the sun has already cleared the horizon. The parking lot is nearly empty and I am so eager to start that I am impatient with the cold-stiff bindings of the snowshoes. Snow fell throughout the day yesterday, silent and steady, and the sky at the base of the mountains remains heavily overcast. But here in the park the sky is radiantly, deeply, purely blue, the rich azure of lapis lazuli. This is a day for adventuring and off I go, feeling a little foolish at first on the well-packed trail at Bear Lake, but then quickly glad of the snowshoes and poles as I begin to break trail in knee-deep powder.

Emerald Lake resembles one of Maxfield Parrish’s paintings in which the foreground is shadowed and the more distant view is brightly lighted. Emerald Lake and its shorelines remain bluish white in the deep shadows of a winter morning, but the snow-covered cliffs to the west and south of the lake are so brilliantly white that the sunlight seems to emanate from them.

The morning is silent but for the sounds I make: no wind, no bird calls. Even the snow avalanches that occasionally cascade from branches mounded under powder make only the softest shshshing as they feather outward in falling through the air. Perhaps it is these thousands of small snow collapses that fill the air with diamond dust. When I look directly upward, even in a broad opening in the forest, the air sparkles with millions of tiny ice crystals reflecting the sunlight. Sunlight fills each opening, coming from above but also from below and from every side, reflected by the infinite mirrors of ice crystals on the ground, coating the trees and rocks, and floating in the air. This is a diamond day of mostly stationary ice crystals tossing the sunlight back and forth in a light show that can feel almost blinding. Such winter days—when snow and sun create the scenery and wind sits in the wings, waiting for its inevitable cue—are rare in the windy heights of Rocky Mountain National Park.

I keep moving, expecting the wind to wake up shortly and start rearranging the precariously poised tufts of snow that both accentuate and obscure every detail of the landscape. Miraculously, the air remains calm and only the gradually increasing warmth of the sun begins the process of rearrangement. More snow bombs start to drop from the trees, occasionally catching me beneath them in a bone-shuddering rush of chill. Clear ice appears at the edges of the spruce needles protruding below mounded snow, precursor of the tiny icicles that form later in the morning. Hoarfrost remains on the shadowed faces of boulders and dead trees, each crystal as intricately patterned as a feather or the frond of a fern. These are the ephemeral flowers of winter, gone as soon as sunlight reaches them or the air warms a little too much. Icicles rib the rock faces below joints. Where the icicles feed on water filtered by the rock, the ice is so clear that even in shadow the diffuse sunlight creates a pattern within the ice that changes as I move from side to side, as though the icicle contained its own fire. Icicles feeding on meltwater moving between snow and soil at the top of the rock form muddy brown streaks down the rock face. Snow, rock, and tree play with my sense of motion and fixity: snow crystals, transient as winter, rest in amorphous piles as though never to move again, while exposed beneath the piles are the twisted wood grain of trees and the contorted layers of rock, each seemingly caught momentarily in an ongoing forceful motion.

I flounder through thigh-deep powder where small avalanches have covered steep portions of the trail to Lake Haiyaha. More snow is moving down from the trees now and I begin to hear the birds. Chickadees call first: reliable, cheerful-sounding, winter-hardy. Then comes the knocking of a woodpecker echoing among the trees. A gray jay flutters in to land on a nearby branch, the usually vocal bird silent today but for the sound of its wings. The jay looks obese, with every feather on its body plumped out to maximize insulation against the killingly cold air. I see a few tracks in the newly fallen powder—the widely spaced leaps of a snowshoe hare or the more delicate imprints of a rodent landing lightly on the surface—but I know that even if the animals spent last night mostly sheltered from the quickly falling snow, they will be seeing about getting food now that the sun is once more bringing warmth.

I lose the trail partway along a steep slope. I feel reasonably sure that the trail switchbacks sharply and continues up the slope, but I can see no evidence of the track, so I continue straight for a few paces. I am quickly floundering, my right snowshoe plunging into a buried air pocket next to a downed tree. The snowshoe partly detaches from my boot and I have trouble pulling it back up to the surface and reattaching it firmly.

Buried cavities in the snow, whether created by obstacles under the snow or by burrowing animals, are critical to winter survival for many creatures. In his fascinating book Winter World, Bernd Heinrich describes ptarmigan and grouse burrowing into snow caves. He also writes of the subnivian zone at the base of the snowpack. Within the snowpack, temperatures are warmer close to the ground. This causes snow crystals to melt, creating water vapor that migrates upward, recondenses, and freezes onto the crystals of the upper snowpack. Over the course of the winter, the lower snowpack develops a subnivian zone analogous to an urban area, with ice pillars and columns forming the skyscrapers and extensive air spaces forming the streets and parks. Temperatures here remain within a degree or two of the freezing point of water, whatever the fluctuations in air temperature up above, thanks to the insulation of the snow and to heat rising from the ground. This subnivian world is the space in which mice, voles, and shrews spend the winter eating insects and the bark of trees and shrubs. The relative warmth of the subnivian also helps some early-blooming wildflowers like pasque flowers get an early start on their annual reproductive cycle.

I have seen the evidence of subnivian activities when melting of the snow in spring and early summer reveals sinuous mounds of sediment churned up by burrowing rodents and packed into subnivian tunnels by the meltwater flowing between the snowpack and the ground surface at the very end of snowmelt. The subnivian world is one of many reasons I am glad that snowmobiles are not allowed in Rocky Mountain National Park. The extensive swaths of compacted snow left across subalpine meadows by snowmobile rodeos in the adjacent national forest lands represent a few minutes’ worth of fun that destroy critical winter habitat for an uncounted number of smaller creatures.

Back at Bear Lake, a short but cautious walk along the heavily trampled and icy snow mounds near the parking lot brings me to the edge of the lake. The lake is a flat, white plain closely surrounded by forest. Sunlight has raised the air temperature above 0°F in the clearings, but the air remains sharply cold in the shadows beneath the trees.

In this seasonal nadir of warmth, I admire the snowy scenery and think about climate warming. I believe that we have to understand the park’s history—from the uplift of the Rockies tens of millions of years ago to the Pleistocene glaciers, the nineteenth-century miners and loggers, and twentieth-century nitrate deposition and water engineering—to understand the contemporary context and future trajectories that might occur in the park. One of the greatest unknowns of the future is how warming climate will change the park. The air will not just get warmer. A likely scenario is that climatic extremes, especially wet, dry, and hot, will become worse. The widespread, sustained rainfall of the September 2013 flood was outside the experience and expectations of anyone living in the region, including meteorologists. After the flood, many people asked, is this climate change? Some of the foremost climate scientists in the world live in Boulder, just east of Rocky Mountain National Park, and the consensus is that because a warming atmosphere holds more moisture, the big flood could be the face of climate change.

Certainly, warming climate will change the punctuated rhythms of climate that have existed for the past several thousand years since the Pleistocene glaciers melted. As climate goes, so goes the world: the rate at which bedrock weathers into sediment, and gravity, water, and ice move the sediment downslope; the types of plants and where they grow; the animals that feed on those plants or on other animals; the number, activity, and geographic range of mountain pine beetles and other insects that kill trees; the water available for people, the crops that can survive the new weather patterns and water availability; the fires that burn the forests and the structures that people build in those forests; and on and on.

I wonder how many of these changes I will actually perceive during my lifetime. I will be preoccupied with my own changing rhythms as I age. Those strenuous annual logjam surveys will not be feasible when I can no longer hike swiftly all day. With luck, I will take pleasure in memories of how I came to know this park from a hundred different entry points over more than a score of years.

For now, back down at Bear Lake, I watch the other visitors moving carefully along the icy trail around the lake. Bear Lake is the microcosm that reflects the diversity of Rocky Mountain National Park. Every park visitor wants to come here. The road to the lake is thick with traffic during summer and on autumn weekends. The lake itself, a scenic gem, is commonly enjoyed in the company of dozens, if not hundreds. But from the lake you can escape the crowds if you are willing to hike. The Flattop Mountain Trail ascends steadily to the continental divide and the paradox of the tundra, where the plants and many of the readily observed animals are diminutive but the world spreads to the expansive horizons. Other trails follow the canyons to the lakes less visited: Emerald, Dream, and Nymph; Haiyaha; Helene, Odessa, and Fern; Loch Vale, Lake of Glass, and Sky Pond; Mills and Black.

Each cascade of lakes has its own beauties and its own secrets. Steep walls of grayish tan granite horizontally seamed by lighter-colored intrusions tightly cup Emerald Lake. Trees and ground junipers lightly colonize the talus at the base of each rock wall and white threads of water in summer and ice in winter twist down from the summits. The talus records the slow crumbling of the rock, but this remains a landscape of rock, on which trees and water make only faint impressions here at the upper limits of their existence. I read the signs of past violence in the swirled intrusions of the rock walls and the wind-combed branches of the trees. Down-valley, Dream Lake occupies an obvious glacial trough where the trees, having more purchase, cover the north-facing slope. The giant, sharp-edged block of Hallett Peak at the northern head of the valley makes me think of how the landscape has been chopped out with a hatchet of ice. Farther down is Nymph Lake, safely cradled by trees, the peaks and their intense winds more distant. Here in summer water lilies bloom yellow in the greenish water.

At Haiyaha rocks emerge from the water at the southern edge, as though colonizing the lake, but the gray, green, and yellowish brown lichens covering the rocks reveal that the boulders moved long ago. The landscape of the lake is mostly quiet now, a rock foundation left to water and plants. In summer, dark stains on the cliff walls reveal water seeping from the seemingly impenetrable rock faces along vertical and horizontal seams where the bedrock leaks. These are the signs of rock falls to come.

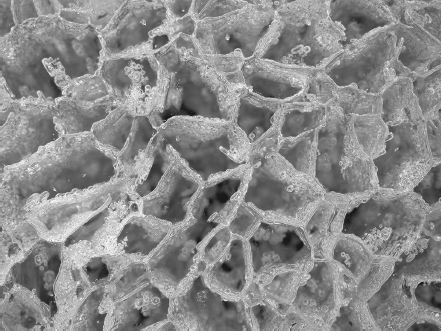

Then there is Loch Vale, which I thought I knew reasonably well, until it revealed a whole new world to me one winter when I chanced to look more carefully down at the ice beneath my feet. Recorded there were the signs of life beneath the seemingly impenetrable lid of ice sealing the lake waters from air and sunlight. The ice held universes of tiny bubbles frozen into little streaks like the tracks of stars moving apart after the Big Bang. Larger bubbles hung arrested in the act of swirling like whirlpools or expanding into a mushroom cloud. Cracks resembled the Milky Way and the honeycomb of a beehive.

→

The next five photographs show different bubbles and cracks in the ice at Loch Vale.

A Personal Park

These are the names and memories that fill in the spaces on the park map. Among them lie the places on my mental map of the park, places that reveal the working of this ecosystem and changes in the landscape through time. At the Storm Pass trailhead near the Bierstadt Lake shuttle bus stop is a relatively small beaver meadow that has at least one active colony of beavers. Here I puzzled over what sort of red-colored fern could grow beneath the waters of a beaver pond until I realized that I was looking at the young shoot of an elephanthead—a plant that grows into a stalk of lovely magenta flowers, each of which resembles the head of an elephant. This beaver meadow was one of the sites where I collected sediment samples to measure how much carbon is stored in the floodplains along different types of valley throughout the park. Active beaver meadows are filled with thick, black muck rich in carbon. These segments of the river network, although only a small portion of total river length, store a disproportionately large amount of the carbon present in the entire landscape. When beavers abandon a meadow, the sediments dry and some of the carbon is released to the atmosphere.

The view west to the high peaks from Storm Pass trailhead along Glacier Creek during summer. A small beaver meadow along the creek is in the foreground.

Beaver meadows and logjams frame my understanding of rivers, wilderness, and climate change in the park. As I contemplate the view from Bear Lake, I imagine individual jams tucked in for the winter beneath snow and ice. Just downstream from Alberta Falls was the huge jam that created a large backwater pool. In autumn, golden leaves fallen from the surrounding aspens floated on the dark water of the pool, collecting together and then drifting apart in a constantly changing mosaic. Then one year the jam vanished, dispersing down Glacier Creek all the rich muck accumulated in the pool, more than a hundred logs, and all the numbered aluminum tags I had laboriously nailed to the logs.

And early on a December morning.

Upstream from Alberta Falls and Mills Lake is the big blowdown of 2011 that created new jams and a complicated pattern of branching channels that flow for 300 yards downstream before rejoining into a single channel. During the first summer, mature trees lay across Glacier Creek like blades of grass felled by the scythe of the wind. Their needles were still green. By the next summer, the branches of these fallen trees had collected other pieces of wood being carried down the creek, forming small logjams. The summer after that, many of the jams and the fallen trees had disappeared, swept away in the flood of September 2013. More trees fell, their roots undercut by stream banks eroded during the flood, or toppled by winter winds, and new jams were starting to form two summers after the flood. These I continue to watch.

And then there is the “Mother Ship,” the jam on North St. Vrain Creek that I first studied in detail with my graduate students. We named it the Mother Ship because it was so large and solid that the intertwined logs and smaller branches created a formidable wall across the creek, backing water 50 yards up the channel in a deep pool carpeted with fine sand and fallen pine needles where fish resting in the eddies waited for an unwary insect to touch down on the water surface. We climbed all over that jam without fear of dislodging the logs or falling into the water. Then one year I noticed a breach in the wall: a suck of water against the right bank swirling downward as though entering the drain in a bathtub. By the next year, wood and sediment were clearly eroding at the widening breach and within two years the once-broad jam was reduced to a narrow, precarious bridge of logs underneath which the creek flowed freely. The pool drained and the fish moved elsewhere, but then another tree fell just upstream, began to catch smaller floating wood, and formed its own jam and backwater pool. This we christened the Daughter Ship.

Each year I finish my annual hikes down the creeks battered and bruised from scrambling through the downed wood away from trails, but intrigued by the changes I have seen since the previous year and happy with my feeling of gradually evolving understanding. Individual jams form and break apart, but as long as some remain present along the forested streams, each jam and its backwater pool create a hot spot where nutrients are stored, habitat is created, and insects and fish grow to abundance.

I enjoy watching the perceptions of my friends and colleagues change as they visit the sections of stream rich in logjams. Even those well versed in the importance of these features are taken aback at the apparent chaos of an old-growth area jumbled with downed wood. As one stream ecologist said on first seeing an old-growth patch along North St. Vrain Creek, “This place looks like a Tinker Toy factory exploded.” With repeated visits, attitudes change from “Whoa, what happened here?” to “Ok, this is one end of the spectrum of ‘normal.’”

Each of us judges the world based on our preconceptions and personal knowledge. My colleagues who study the chemistry of the Loch Vale ecosystem are concerned because they know that nitrates are accumulating in the soils and water. When I hike through the old-growth forest along North St. Vrain Creek early on a summer morning with newly hatched mayflies and rising mist backlit by the rising sun, all’s right with the world. When I compare the abundance and diversity of the active beaver meadow at Wild Basin with the biologically poorer abandoned beaver sites now changed to dry grasslands in Moraine Park and Upper Beaver Meadows, all is not so right.

Paradoxes

As I stand at Bear Lake at the end of the year, I ponder the paradoxes of the park, a highly managed and relatively altered “wilderness” in which more than 3 million visitors a year trample heavily used sections of trail to dust and require bigger roads and campgrounds. I am continually tripped up by my own false expectations that the park will be a wilderness in which humans have had no part. I chide myself that these are Romantic fantasies. I remember one summer morning when I worked in Upper Beaver Meadows during the reconstruction of the Bear Lake Road. I was just thinking sourly that I might as well be down in a city with all the noise of the heavy equipment, when I saw five wild turkeys crossing the meadow. Then a coyote trotted by, pausing to cock its head sideways and listen to something moving in the grass before pouncing in a high arc on a small rodent. I walked into a stand of aspen at the edge of the valley and found an elk lying down, chewing placidly. Clearly, at least some of the local wildlife was not particularly perturbed by the construction noise.

Why does it matter so much if humans have altered this landscape? It matters because the history of alteration means that we are not starting from an intact ecosystem, complete with predators, for example, and we must therefore continue to actively intervene in the workings of this ecosystem. It matters because our property boundaries and land uses truncate ecosystems, migration routes, and habitat. Beavers, for example, may do better outside the national park, on adjacent national forest lands where elk are hunted. And it matters because we as a society cannot pat ourselves on the back and assume that we are finished because we have set aside a few natural areas in the national park system. We have managed to designate some less altered parcels of land, but there is no true wilderness in a time of human-induced climate warming. We cannot assume the luxury that there is some “away” or “apart,” whether this is Rocky Mountain National Park or Alaska, because there no longer is.

I do not think this is cause for despair. Language matters: how we phrase and frame an issue or a question strongly influences how we think about responses or solutions to it. Are some of the changes in Rocky Mountain National Park during the past century human caused? Yes. Am I part of the cause? Yes. Is the response or solution beyond my influence? No. As one of my friends who is a climate scientist put it, we have an obesity problem in the United States. Do we blame calories? Do we blame farmers? Of course not. We put the blame on many other factors, including individual choices. We could apply the same reasoning to climate change, water engineering, atmospheric deposition, or extinction of species. These effects stem from many causes, including our individual choices.

My great-grandmother visited Rocky Mountain National Park as an elderly woman in 1930. I have a souvenir from that trip, a brochure issued by the Union Pacific System titled Colorado Mountain Playgrounds. I like to look at the black-and-white photographs of people in open touring cars driving between tall snow banks along Trail Ridge. One of the photos shows Bear Lake, which the caption describes as “sought because of its seclusion and primitive beauty.” No one would describe Bear Lake as secluded today. The enormous parking lot quickly fills on summer mornings and those who don’t rise with the sun can only reach the lake by shuttle bus. As beautiful as I find Bear Lake, this is why I seek the backcountry.

Photograph of Bear Lake in a 1930 Union Pacific railroad brochure. The large number of standing dead trees across the lake reflects the Bear Lake fire of 1900, which was started by an abandoned campfire.

My research has provided an entrée into seldom-traveled portions of the park and that is without question one of the attractions of research for me. I enjoy the physical challenge of accessing remote streams and I appreciate my greater awareness of the surroundings when I work alone. Of equal importance, I am compelled by scientific questions about how rivers function under different conditions imposed by natural processes and by humans. These questions evolve with time as my understanding of the park environment changes. I have a history with sites visited year after year and this enhances my appreciation of the impact of episodic events such as the very high snowmelt flows of 2010 and 2011, the blowdowns during the winter of 2011–2012, or the drought of 2012. The logjams and beaver meadows to which I return each summer are my grains of sand in which I see the world.

A view of Bear Lake during winter 2010 indicates regrowth of the forest after the fire.

Among the famous, heavily visited parks of the western United States—Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Glacier—Rocky Mountain is relatively small and closely hemmed in by cities and agricultural lands. As I learn more about this national park, I find myself frequently mourning what has been lost: the extensive beaver meadows; pools with dozens of native trout; and wolves, grizzlies, wolverines, and bison. It is as though I see the ghosts of these animals when I come upon long-abandoned beaver dams far up a mountain stream or see the nineteenth-century photographs of men posing with dozens of cutthroat trout strung up behind them.

But even greater than the urge to mourn is the desire to celebrate what remains. One of the qualities that makes this park special to me is its very proximity to my home. I live in an average suburban neighborhood in an average city, but in an hour I can be at a trailhead that is the portal to a place where humans do not necessarily dominate and where natural communities continue to surprise and enlighten. This is a central paradox of the park: it is so close to so many people that it is heavily used, yet its accessibility allows me to return repeatedly and come to know the landscape from different entry points through the seasons and the years. I love this park, and even though I am sometimes disappointed by what I learn of its history, love is not love which alters when it alteration finds. Rocky Mountain National Park remains the closest thing I know to the truth of this natural landscape.

This love and this sense of truth are what impel me to examine and question my individual choices and the choices of my society through a lens of what choices are best for the natural world. I do not have simple answers to the very difficult questions of how the national park service and concerned citizens can reduce problems starting outside the park boundaries or before the park was established, but I strongly believe that each of us must be aware of problems before we can know best what to do. My awareness leads me to embrace messiness—to revel in the physical complexity supported by beaver dams and logjams, as well as by blowdowns and wildfires—and to celebrate natives over introduced species. Awareness allows me to move beyond a view of the landscapes and ecosystems of the national park as static scenery and understand them as dynamic features continually changing over time periods short and long. I strive to see beyond obvious perceptions to the cryptic processes such as water moving down hillslopes to emerge in wet meadows perched above a stream, where my passage flushes songbirds nesting in the knee-high willow shrubs.

Sometimes this striving to see beyond the obvious is hard work. Despite my knowledge of natural extremes, Rocky Mountain National Park is not a place where I expect to directly experience natural disasters. I have worked in the Himalaya and been continually aware of the possibility of rock falls and landslides. And I have worked in the tropics and kept the proverbial one eye open for epiphyte-laden trees that come crashing down when even modest winds follow prolonged rain. But the park still strikes me as relatively benign. I hiked up to one of my remote sites on North St. Vrain Creek on Tuesday, September 10, 2013, the day before widespread flooding began. I had no inkling of what was occurring. Rain had fallen the day before and we had a chilly, damp day as moderate rain continued to fall steadily that Tuesday, but I never would have predicted that we were about to experience a major flood.

Scientists place a great deal of value on objectivity and are the first to criticize each other for not being objective. I could be the vaunted objective scientist and simply observe human alterations in the park while remaining emotionally detached, but this goes against my conscience. I am emotionally invested in this splendid place, not least because of my knowledge of some of its workings. (It’s so cool, how can we stand to destroy it?) More than a decade ago, I attended a scientific workshop on reducing the effects of dams on river ecosystems. One scientist at the workshop lamented the increasing tendency of his colleagues to speak out about the damage done by dams to fish and river ecosystems. He traced this unfortunate tendency toward advocacy back to Rachel Carson. I left the workshop at the end of the day incensed and took a long walk in the woods surrounding the meeting place. Besides my deep admiration of Rachel Carson, his comments upset me because of my growing conviction that the special knowledge developed by scientists regarding the systems we study compels us to speak out. I have a responsibility to explain exactly what downed wood, and beavers, and physically complex rivers mean for biodiversity, water quality, and resilient ecosystems. I cannot dictate anyone else’s behavior based on that knowledge, but I can work to ensure that our behavior does not result from ignorance of how we affect the world around us. There will likely always be people who do not care, no matter how much scientists strive to communicate their understanding of the complex and fascinating workings of natural systems. But my experience has been that many people do care and, if they are made aware of how human activities cause changes, prefer to cause fewer changes in national park ecosystems. We are all part of the problem and we are all part of the solution.