Psychology Is a Science

Underlying all science is, first, a passion to explore and understand without misleading or being misled. Some questions (Is there life after death?) are beyond science. Answering them in any way requires a leap of faith. With many other ideas (Can some people demonstrate ESP?), the proof is in the pudding. Let the facts speak for themselves.

Magician James Randi has used a scientific approach when testing those claiming to see glowing auras around people’s bodies:

Randi: Do you see an aura around my head?

Aura seer: Yes, indeed.

Randi: Can you still see the aura if I put this magazine in front of my face?

Aura seer: Of course.

Randi: Then if I were to step behind a wall barely taller than I am, you could determine my location from the aura visible above my head, right?

Randi once told me [DM] that no aura seer had agreed to take this simple test.

The Amazing Randi The magician James Randi exemplifies skepticism. He has tested and debunked supposed psychic phenomena.

No matter how sensible-seeming or how wild an idea, the smart thinker asks: Does it work? When put to the test, do the data support its predictions? Subjected to such scrutiny, crazy-sounding ideas sometimes find support. During the 1700s, scientists scoffed at the notion that meteorites had extraterrestrial origins. When two Yale scientists challenged the conventional opinion, Thomas Jefferson reportedly jeered, “Gentlemen, I would rather believe that those two Yankee professors would lie than to believe that stones fell from Heaven.” Sometimes scientific inquiry turns jeers into cheers.

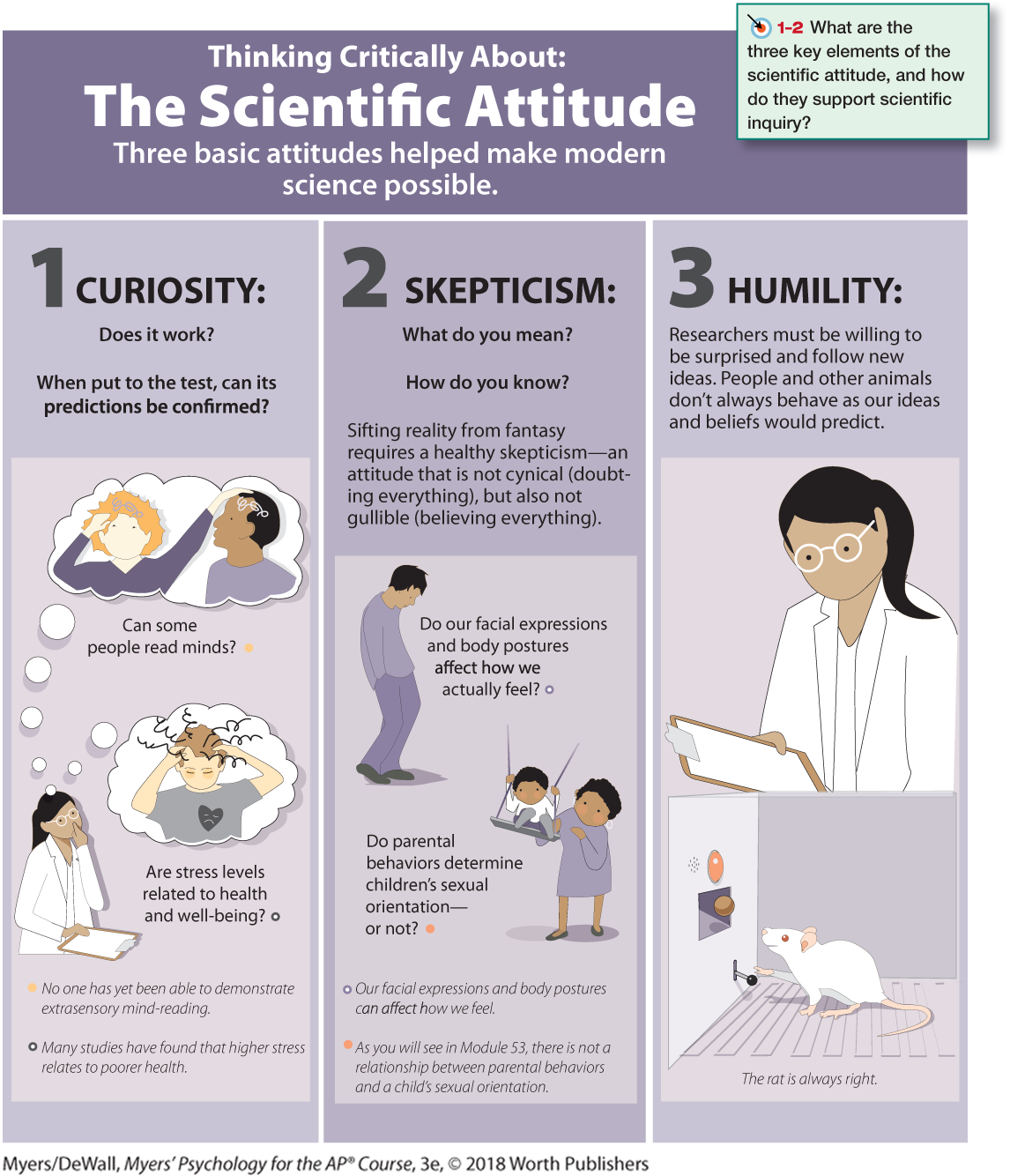

More often, science becomes society’s garbage disposal, sending crazy-sounding ideas to the waste heap, atop previous claims of perpetual motion machines, miracle cancer cures, and out-of-body travels into centuries past. To sift reality from fantasy, sense from nonsense, verified facts from fake news, therefore requires a scientific attitude: being skeptical but not cynical, open but not gullible. When ideas compete, careful testing can reveal which ones best match the facts. Can astrologers predict your future based on the planets’ position at your birth? Is electroconvulsive therapy (delivering an electric shock to the brain) an effective treatment for severe depression? As we will see, putting such claims to the test has led psychological scientists to answer No to the first question and Yes to the second.

Putting a scientific attitude into practice requires not only curiosity and skepticism but also humility—an awareness of our own vulnerability to error and an openness to new perspectives. What matters is not my opinion or yours, but the truths revealed by our questioning and testing. If people or other animals don’t behave as our ideas predict, then so much the worse for our ideas. This humble attitude was expressed in one of psychology’s early mottos: “The rat is always right.” (See Thinking Critically About: The Scientific Attitude.)