Module 38 Hunger Motivation

As dieters know, physiological needs are powerful. This was vividly demonstrated when Ancel Keys and his research team (1950) studied semistarvation among wartime volunteers who participated in a challenging experiment as an alternative to military service. After feeding 200 men normally for three months, researchers halved the food intake for 36 of them. These semistarved men became listless and apathetic as their bodies conserved energy. Eventually, their body weights stabilized about 25 percent below their starting weights.

More dramatic were the psychological effects. Consistent with Maslow’s idea of a needs hierarchy, the men became food obsessed. They talked food. They daydreamed food. They collected recipes, read cookbooks, and feasted their eyes on delectable forbidden foods. Preoccupied with their unfulfilled basic need, they lost interest in sex and social activities. As one participant reported, “If we see a show, the most interesting part of it is contained in scenes where people are eating. I couldn’t laugh at the funniest picture in the world, and love scenes are completely dull.” The men’s preoccupations illustrate how powerful motives can hijack our consciousness. As journalist Dorothy Dix (1861–1951) observed, “Nobody wants to kiss when they are hungry.”

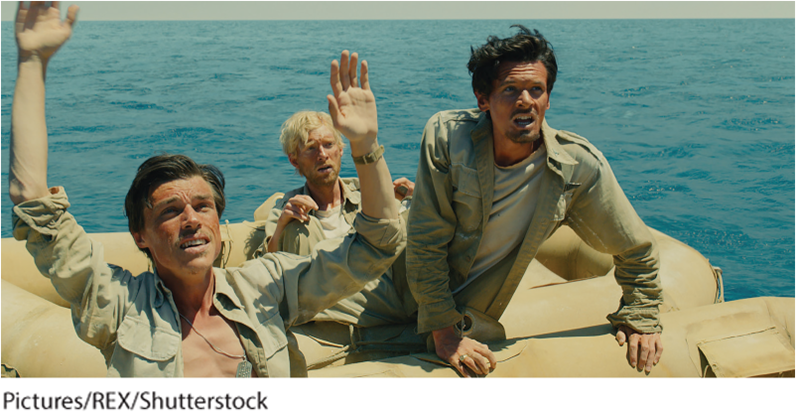

Hunger hijacks the mind World War II survivor Louis Zamperini (protagonist of the book and movie Unbroken, shown here) went down with his plane over the Pacific Ocean. He and two other crew members drifted for 47 days, subsisting on an occasional bird or a fish. To help pass time, the hunger-driven men recited recipes or recalled their mothers’ home cooking.

“ Hunger is the most urgent form of poverty.”

Alliance to End Hunger, 2002

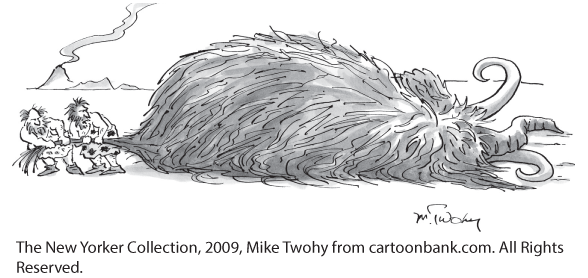

When you are hungry, thirsty, fatigued, or sexually aroused, little else may seem to matter. In University of Amsterdam studies, Loran Nordgren and his colleagues (2006, 2007) found that people in a motivational “hot” state (from fatigue, hunger, or sexual arousal) easily recalled such feelings in their own past and perceived them as driving forces in others’ behavior. (You may recall from Module 32 a parallel effect of our current good or bad mood on our memories of good or bad moods.) In another experiment, people were given money to bid for foods. When hungry, people overbid for snacks they were told they could eat later when they would be full. When full, people underbid for snacks they were told they could eat later when they would be hungry (Fisher & Rangel, 2014). It’s hard to imagine what we’re not feeling! Likewise, when sexually motivated, men more often perceive a smile as flirtation rather than simple friendliness (Howell et al., 2012). Grocery shop with an empty stomach and you are more likely to see those jelly-filled doughnuts as just what you’ve always loved and will be wanting tomorrow. Motives matter mightily.

“Never hunt when you’re hungry.”

“ The full person does not understand the needs of the hungry.”

Irish proverb