Promoting Health

Promoting health begins with implementing strategies that prevent illness and enhance wellness. Traditionally, people have thought about their health only when something goes wrong and they visit a physician. That, say health psychologists, is like ignoring a car’s maintenance and going to a mechanic only when the car breaks down. Health maintenance includes alleviating stress, preventing illness, and promoting well-being.

Explanatory Style: Optimism Versus Pessimism

One aspect of our health and our coping is our outlook—what we expect from the world. Pessimists expect things to go badly (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010; Carver et al., 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2009). When bad things happen, pessimists knew it all along. They attribute their poor performance to a basic lack of ability (“I can’t do this”) or to situations enduringly beyond their control (“There is nothing I can do about it”). Optimists expect to have more control, to cope better with stressful events, and to enjoy better health (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010; Boehm & Kubzansky, 2012; Hernandez et al., 2015). During a semester’s last month, students previously identified as optimistic reported less fatigue and fewer coughs, aches, and pains. And during the stressful first few weeks of law school, those who were optimistic (“It’s unlikely that I will fail”) enjoyed better moods and stronger immune systems (Segerstrom et al., 1998). Optimists also respond to stress with smaller increases in blood pressure, and they recover more quickly from heart bypass surgery.

Optimistic students have also tended to get better grades because they often respond to setbacks with the hopeful attitude that effort, good study habits, and self-discipline make a difference (Noel et al., 1987; Peterson & Barrett, 1987). When dating couples wrestle with conflicts, optimists and their partners see each other as engaging constructively, and they then tend to feel more supported and satisfied with the resolution and with their relationship (Srivastava et al., 2006). Optimism relates to well-being and success in many places, including China and Japan (Qin & Piao, 2011). Realistic positive expectations fuel motivation and success (Oettingen & Mayer, 2002).

Consider the consistency and startling magnitude of the optimism and positive emotions factor in several other studies:

- When one research team followed 70,021 nurses over time, they discovered that those scoring in the top quarter on optimism were nearly 30 percent less likely to have died than those scoring in the bottom 25 percent (Kim et al., 2017). Even greater optimism-longevity differences have been found in studies of Finnish men and American Vietnam-era veterans (Everson et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 2009).

- A famous study followed up on 180 Catholic nuns who had written brief autobiographies at about 22 years of age and had thereafter lived similar lifestyles. Those who had expressed happiness, love, and other positive feelings in their autobiographies lived an average 7 years longer than their more dour counterparts (Danner et al., 2001). By age 80, some 54 percent of those expressing few positive emotions had died, as had only 24 percent of the most positive-spirited.

“ The optimist proclaims we live in the best of all possible worlds; and the pessimist fears this is true.”

James Branch Cabell, The Silver Stallion, 1926

Optimism runs in families, so some people truly are born with a sunny, hopeful outlook. If one identical twin is optimistic, the other often will be as well (Bates, 2015; Mosing et al., 2009). One genetic marker of optimism is a gene that enhances the social-bonding hormone oxytocin, which in humans is released, for example, by cuddling, massage, and breast-feeding (Campbell, 2010; Saphire-Bernstein et al., 2011).

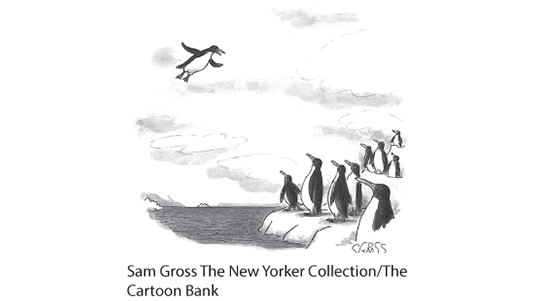

“We just haven’t been flapping them hard enough.”

Positive expectations often motivate eventual success.

The good news is that all of us, even the most pessimistic, can learn to become more optimistic. Compared with a control group of pessimists who simply kept diaries of their daily activities, pessimists in a skill-building group—who learned ways of seeing the bright side of difficult situations and of viewing their goals as achievable—reported lower levels of depression (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2014). Optimism is the light bulb that can brighten anyone’s mood.

Social Support

Social support—feeling liked and encouraged by intimate friends and family—promotes both happiness and health. In massive investigations, some following thousands of people for several years, close relationships have predicted happiness and health in both individualist and collectivist cultures (Brannan et al., 2013; Gable et al., 2012; Rueger et al., 2016). People are less likely to die early if supported by close relationships (Shor et al., 2013). When Brigham Young University researchers combined data from 70 studies of 3.4 million people worldwide, they confirmed a striking effect of social support (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Compared with those who had ample social connections, those who were socially isolated or felt lonely had a 30 percent greater death rate during the 7-year study period. Social isolation’s association with risk of death is equivalent to smoking (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

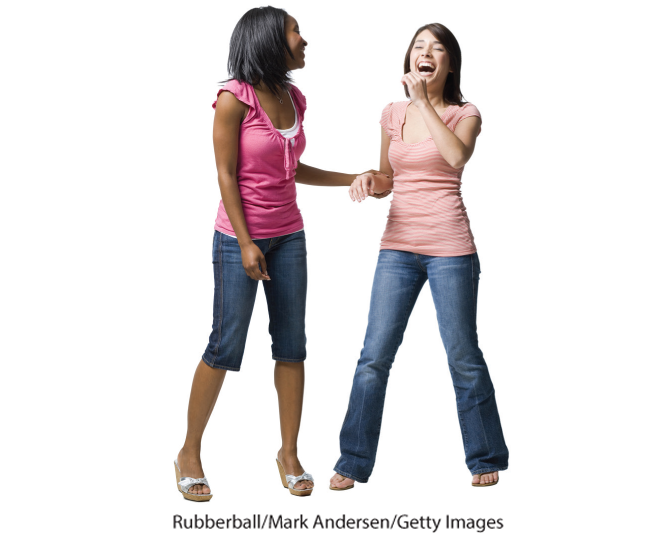

Laughter among friends is good medicine Laughter arouses us, massages muscles, and then leaves us feeling relaxed (Robinson, 1983). Humor (though not hostile sarcasm) may defuse stress, ease pain, and strengthen immune activity (Ayan, 2009; Berk et al., 2001; Dunbar et al., 2011; Kimata, 2001). People who laugh a lot have also tended to have lower rates of heart disease (Clark et al., 2001).

To combat social isolation, we need to do more than collect lots of acquaintances. We need people who genuinely care about us (Cacioppo et al., 2014; Hawkley et al., 2008). Some fill this need by connecting with friends, family, co-workers, members of a faith community, or other support groups. Others connect in positive, happy, supportive marriages. One 7-decade-long study found that at age 50, healthy aging was better predicted by a good marriage than by a low cholesterol level (Vaillant, 2002). On the flip side, divorce predicts poor health. In one analysis of 32 studies involving more than 6.5 million people, divorced people were 23 percent more likely to die early (Sbarra et al., 2011). But it’s less marital status than marital quality that predicts health—to about the same extent as a healthy diet and physical activity do (Robles, 2015; Robles et al., 2014).

What explains the link between social support and health? Are middle-aged and older adults who live alone more likely to smoke, be obese, and have high cholesterol—and therefore to have a doubled risk of heart attacks (Nielsen et al., 2006)? Or are healthy people simply more sociable? Possibly. But research suggests that social support does have health benefits.

SOCIAL SUPPORT CALMS US AND REDUCES BLOOD PRESSURE AND STRESS HORMONES

(Baron et al., 2016; Hostinar et al., 2014; Uchino et al., 1996, 1999). To see if social support might calm people’s response to threats, one research team subjected happily married women, while lying in an fMRI machine, to the threat of electric shock to an ankle (Coan et al., 2006). During the experiment, some women held their husband’s hand. Others held the hand of an unknown person or no hand at all. While awaiting the occasional shocks, women holding their husband’s hand showed less activity in threat-responsive areas. This soothing benefit was greatest for those reporting the highest-quality marriages. People with supportive marriages also had below-average stress hormone levels 10 years later (Slatcher et al., 2015). Even animal support, such as a companionable pet, helps buffer stress (Siegel, 1990).

SOCIAL SUPPORT FOSTERS STRONGER IMMUNE FUNCTIONING

Volunteers in studies of resistance to cold viruses showed this effect (Cohen, 2004; Cohen et al., 1997). Healthy volunteers inhaled nasal drops laden with a cold virus and were quarantined and observed for 5 days. (In these experiments, more than 600 volunteers received $800 each to endure this experience.) Age, race, sex, and health habits being equal, those with close social ties were least likely to catch a cold. People whose daily life included frequent hugs likewise experienced fewer cold symptoms and less symptom severity (Cohen et al., 2015). The cold fact is that the effect of social ties is nothing to sneeze at!

Pets are friends, too Pets can provide social support. Having a pet may increase the odds of survival after a heart attack, relieve depression among people with AIDS, and lower blood pressure and other coronary risk factors (Allen, 2003; McConnell et al., 2011; Wells, 2009). To lower blood pressure, pets are no substitute for effective drugs and exercise. But for people who enjoy animals, and especially for those who live alone, pets are a healthy pleasure (Allen, 2003).

CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS GIVE US AN OPPORTUNITY FOR “OPEN HEART THERAPY”—A CHANCE TO CONFIDE PAINFUL FEELINGS

(Frattaroli, 2006). Talking about a stressful event can temporarily arouse us, but in the long run it calms us (Lieberman et al., 2007; Mendolia & Kleck, 1993; Niles et al., 2015). In one study, 33 Holocaust survivors spent two hours recalling their experiences, many in intimate detail never before disclosed (Pennebaker et al., 1989). In the weeks following, most watched a video of their recollections and showed it to family and friends. Those who were most self-disclosing had the most improved health 14 months later. In another study, of surviving spouses of people who had committed suicide or died in car accidents, those who bore their grief alone had more health problems than those who shared it with others (Pennebaker & O’Heeron, 1984). Confiding is good for the body and the soul.

Suppressing emotions can be detrimental to physical health. When psychologist James Pennebaker (1985) surveyed more than 700 undergraduate women, some reported a traumatic sexual experience in childhood. The sexually abused women—especially those who had kept their secret to themselves—reported more headaches and stomach ailments than did other women who had experienced nonsexual traumas, such as parental death or divorce. Another study, of 437 Australian ambulance drivers, confirmed the ill effects of suppressing one’s emotions after witnessing traumas (Wastell, 2002).

“ Woe to one who is alone and falls and does not have another to help.”

Ecclesiastes 4:10

Even writing about personal traumas in a diary can help (Burton & King, 2008; Kállay, 2015; Lyubomirsky et al., 2006). In an analysis of 633 trauma victims, writing therapy was as effective as psychotherapy in reducing psychological trauma (van Emmerik et al., 2013). In another experiment, volunteers who wrote trauma diaries had fewer health problems during the ensuing 4 to 6 months (Pennebaker, 1990). As one participant explained, “Although I have not talked with anyone about what I wrote, I was finally able to deal with it, work through the pain instead of trying to block it out. Now it doesn’t hurt to think about it.”

If we are aiming to exercise more, eat less, or reach our full academic potential, our social ties can tug us away from or toward our goal. If you are trying to achieve some goal, think about whether your social network will help or hinder you.