Evaluating Humanistic Theories

One thing said of Freud can also be said of the humanistic psychologists: Their impact has been pervasive. Maslow’s and Rogers’ ideas have influenced counseling, education, child raising, and management. And they laid the groundwork for today’s scientific positive psychology subfield (Module 44).

These theorists have also influenced—sometimes in unintended ways—much of today’s popular psychology. Is a positive self-concept the key to happiness and success? Do acceptance and empathy nurture positive feelings about ourselves? Are people basically good and capable of self-improvement? Many people answer Yes, Yes, and Yes. In 2006, U.S. high school students reported notably higher self-esteem and greater expectations of future career success than did students living in 1975 (Twenge & Campbell, 2008). Given a choice, today’s North American college students mostly say they’d rather get a self-esteem boost, such as a compliment or good grade on a paper, than enjoy a favorite food (Bushman et al., 2011). Humanistic psychology’s message has been heard.

But the prominence of the humanistic perspective set off a backlash of criticism. First, said the critics, its concepts are vague and subjective. Consider Maslow’s description of self-actualizing people as open, spontaneous, loving, self-accepting, and productive. Is this a scientific description? Or is it merely a description of the theorist’s own values and ideals? Maslow, noted M. Brewster Smith (1978), offered impressions of his own personal heroes. Imagine another theorist who began with a different set of heroes—perhaps Napoleon, John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and U.S. President Donald Trump. This theorist would likely describe self-actualizing people as “undeterred by others’ opinions,” “motivated to achieve,” and “comfortable with power.”

Critics also objected to the idea that, as Rogers (1985) put it, “The only question which matters is, ‘Am I living in a way which is deeply satisfying to me, and which truly expresses me?’” This emphasis on individualism—trusting and acting on one’s feelings, being true to oneself, fulfilling oneself—could lead to self-indulgence, selfishness, and an erosion of moral restraint (Campbell & Specht, 1985; Wallach & Wallach, 1983). Imagine working on a group project with people who refuse to complete any task that is not deeply satisfying or does not truly express their identity.

Humanistic psychologists have replied that a secure, nondefensive self-acceptance is actually the first step toward loving others. Indeed, people who feel intrinsically liked and accepted—for who they are, not just for their achievements—exhibit less defensive attitudes (Schimel et al., 2001). Those feeling liked and accepted by a romantic partner report being happier in their relationships and acting more kindly toward their partner (Gordon & Chen, 2010).

“We do pretty well when you stop to think that people are basically good.”

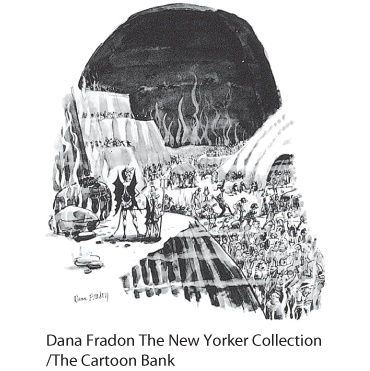

A final accusation leveled against humanistic psychology is that it is naive—that it fails to appreciate the reality of our human capacity for evil (May, 1982). Faced with climate change, overpopulation, terrorism, and the spread of nuclear weapons, we may become apathetic from either of two rationalizations. One is a starry-eyed optimism that denies the threat (“People are basically good; everything will work out”). The other is a dark despair (“It’s hopeless; why try?”). Action requires enough realism to fuel concern and enough optimism to provide hope. (Pessimism often fulfills its own predictions by restraining our efforts at change.) Humanistic psychology, say the critics, encourages the needed hope but not the equally necessary realism.