Evaluating Alternative Therapies

The tendency of many abnormal states of mind to return to normal, combined with the placebo effect (the healing power of mere belief in a treatment), creates fertile soil for pseudotherapies. Bolstered by anecdotes, boosted by the media, and broadcast on the Internet, alternative therapies—newer, nontraditional therapies, which often claim healing powers for various ailments—can spread like wildfire. In one national survey, 57 percent of those with a history of anxiety attacks and 54 percent of those with a history of depression had used alternative treatments, such as herbal medicine and spiritual healing (Kessler et al., 2001).

Proponents of alternative therapies often feel that their personal testimonials are evidence enough. But how well do these therapies stand up to scientific scrutiny? There is little evidence for or against most of them. Some, however, have been the subject of controlled research. No prizes—and no scientific support—go to certain alternative therapies (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2006; Lilienfeld et al., 2015). We would all be wise to avoid energy therapies that propose to manipulate the client’s invisible “energy fields,” hand-guided facilitated communication with uncommunicative people, recovered-memory therapies that aim to unearth “repressed memories” of early child abuse (Module 33), and rebirthing therapies that reenact the supposed trauma of a client’s birth.

As with medical treatments, some psychological treatments are not only ineffective but also harmful (Barlow, 2010; Castonguay et al., 2010; Dimidjian & Hollon, 2010). The National Science and Technology Council has cited the Scared Straight program (seeking to deter children and youth from crime by having them visit with adult inmates) as an example of one such well-intentioned but ineffective program. The American Psychiatric Association and British Psychological Society have warned against “conversion therapy” for those with same-sex attractions. Conversion therapies, including “reparative therapy,” aim to “repair” “something that is not a mental illness and therefore does not require therapy,” declared American Psychological Association president Barry Anton (2015). “There is insufficient scientific evidence that they work, and they have the potential to harm the client.”

Let’s look more closely at two other alternative therapies. As we do, remember that sifting sense from nonsense requires the scientific attitude: being skeptical but not cynical, open to surprises but not gullible.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) is a therapy adored by thousands and dismissed by thousands more as a sham. Psychologist Francine Shapiro (1989, 2007, 2012) developed EMDR while walking in a park and observing that anxious thoughts vanished as her eyes spontaneously darted about. Back in the clinic, she had people imagine traumatic scenes while she triggered eye movements by waving her finger in front of their eyes, supposedly enabling them to unlock and reprocess previously frozen memories. Thousands of mental health professionals from more than 75 countries have since undergone training (EMDR, 2011).

Does EMDR work? Shapiro (1999, 2002) believes it does, and she cites four studies in which it worked for 84 to 100 percent of single-trauma victims. Other studies have confirmed its benefits with trauma survivors (Chen et al., 2015). But why, wonder skeptics, would rapidly moving one’s eyes while recalling traumas be therapeutic? Some argue that eye movements relax or distract patients, thus allowing memory-associated emotions to extinguish (Gunter & Bodner, 2008). (Part of therapeutic change is calling up old memories and associating them with new emotions [Lane et al., 2015].) Others believe the eye movements themselves are not the therapeutic ingredient (nor is watching high-speed Ping-Pong therapeutic). Trials in which people imagined traumatic scenes and tapped a finger, or just stared straight ahead while the therapist’s finger wagged, have also produced therapeutic results (Devilly, 2003).

“ Studies indicate that EMDR is just as effective with fixed eyes. If that conclusion is right, what’s useful in the therapy (chiefly behavioral desensitization) is not new, and what’s new is superfluous.”

Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2002

Skeptics acknowledge that EMDR does work better than doing nothing (Lilienfeld & Arkowitz, 2007). But they suspect that what is therapeutic is the combination of exposure therapy—repeatedly calling up traumatic memories and reconsolidating them in a safe and reassuring context—and perhaps some placebo effect.

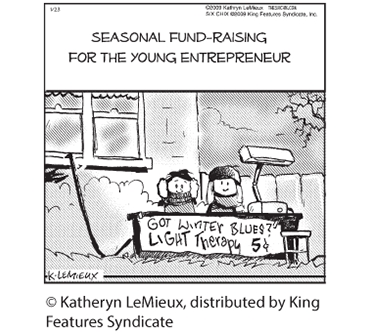

Light Exposure Therapy

Have you ever found yourself oversleeping, gaining weight, and feeling lethargic, perhaps during the dark mornings and overcast days of winter? Slowing down and conserving energy during the cold, barren winters may have given our distant ancestors a survival advantage. To counteract lethargy, National Institute of Mental Health researchers in the early 1980s had an idea: Give people a timed daily dose of intense light. Sure enough, people reported they felt better.

Was light exposure a bright idea, or another dim-witted example of the placebo effect? Research illuminates the issue. One study exposed some people with a seasonal pattern in their depression symptoms to 90 minutes of bright light and others to a sham placebo treatment—a hissing “negative ion generator” about which the staff expressed similar enthusiasm (but which was actually just producing white noise). After four weeks, 61 percent of those exposed to morning light had greatly improved, as had 50 percent of those exposed to evening light and 32 percent of those exposed to the placebo (Eastman et al., 1998).

Some studies have cast a shadow on light exposure therapy. Nevertheless, others have shown that 30 minutes of morning exposure to 10,000-lux white fluorescent light produces relief for most depressed people. Moreover, it does so as effectively as taking antidepressant drugs or undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy (Lam et al., 2006, 2016; Rohan et al., 2007, 2015). Brain scans help explain the benefit: Light therapy sparks activity in a brain region that influences the body’s arousal and hormone levels (Ishida et al., 2005).

Light therapy To counteract depression, some people spend time each morning exposed to intense light that mimics natural outdoor light. Light boxes are available from health supply and lighting stores.