CHAPTER FOUR:

The Fundamentals of Building Your Asset Base

"Success is the ability to go from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm."

—Sir Winston Churchill

In building an investment portfolio, there are many places where you can invest your money. To the average investor, making decisions about where to invest your money is very confusing. There are many people who will not act in your best interests; rather they act in a manner which benefits them. A common example is a real estate agent or property promoter advising you to buy an investment property. This section of the book examines the various places in which you can invest your monies and how to determine whether these investments are suitable to for you. There is no short cut and you need to do your own research. If an offer appears too good to be true, it probably is, and you are better off avoiding this. Each investment has its own advantages, disadvantages, risks and potential returns. As a consequence of this, each individual investment needs to be considered on its own merits.

As a starting point, there are two basic types of assets: those that go up in value, and those that go down in value. Let's look at these in more detail.

Bad Assets – those that go down in value

I have classified those assets that we buy and go down in value as bad assets. Bad assets are often lifestyle assets. We all buy items that go down in value and we cannot live life without buying them. Examples include clothes, electrical appliances, motor vehicles, and recreational equipment—surf boards, bikes, golf clubs, etc. The secret is to minimise the amount, which you spend on these items and the amount you borrow to pay for them. For example, the cost of buying a new motor vehicle may be $50,000, but buying a motor vehicle less than six months old saves you around 15%, so buying one twelve months old saves you over 30%.

Borrowing for assets that go down in value is another area where you need to be careful. There have been many documented cases where a person still owes money on an asset, but the asset no longer exists. An example is a television that no longer works. The interest rates on this type of loan tend to be significantly higher than loans secured against a physical, appreciating asset. This reflects the higher risk associated with this type of loan with no security.

The great temptation we all face is to buy items today that give us instant gratification, such as new clothes or a new windsurfer, and the thought of putting the money away for a rainy day is not appealing to most people. The secret is to strike a balance between the two by doing both.

Good Assets – those that go up in value

One of the key concepts to achieving financial security is to buy assets that appreciate over time. In theory, this means that your financial position is forever improving. However, it is not as simple as that, as there are impediments that we all encounter along the way, such as the Global Financial Crisis that we cannot avoid. The result is that the value of the good assets falls. In periods of uncertainty, it is important to maintain the long term focus and avoid short term issues. This is often easier said than done. It does not really matter what you buy, as long as it goes up in value. For example, a colleague has a passion for motor vehicles and, after doing his research, purchased a limited edition Peter Brock Holden Commodore for $300,000. Initially, this seemed like a waste of money, as we all know cars go down in value once you buy them. Well, I was wrong, as there is a certain segment of the population out there that absolutely loves their cars and do not mind what they pay for rare cars. Added to this was the fact that Peter Brock died and, all of a sudden, the car became a collector's item. My colleague then sold the car for $500,000. This was difficult to believe. I am not for a moment advocating buying limited edition cars as a wealth creation strategy, but this is an example of an opportunity that existed at that time, and a person who had a great interest in collector cars was able was to make the most of both his interest and knowledge to make a profit.

We are all aware of the sort of assets that are likely to go up in value. For example, property in areas where the population is increasing; rare items, such as stamps, coins; and shares in companies whose profits are rising. The secret is to share in this growth by using your savings to buy a stake in an appreciating asset. Most people recognise a general opportunity that is going to increase in value, property by the sea is a good example, but do not act upon it. If you want to build your assets and you make the decision to do so, then you need to make certain decisions. Taking the plunge at some point and making decisions is necessary to start building your wealth. You won't ever attain true financial independence having your savings sitting in a bank account or under the bed. Remember: what is difficult at first becomes progressively easier through practice. In other words, once you make a start, it will become easier as the appropriate behaviours for developing your assets becomes a habit.

The concept of diversification

When building an investment portfolio, it is important to diversify your asset base to reduce the risks associated with having all of your eggs in the one basket. A very simple way of explaining the merits of diversification is by imagining that you have twenty pencils in hand and one pencil breaks. You now have nineteen pencils in your hand. On the other hand if you have one pencil in your hand and it breaks, you have no more pencils. The same principle can be used when building an investment portfolio.

There are many examples detailed in the media, where a person had all of their wealth in one company or property and, after a major event such as the GFC, all of their wealth disappeared along with that investment. A recent example was Tony Smith, who built his wealth on the Break Free resort management company, which he sold to a listed entity known as MFS Limited, now known as Octaviar, for approximately $65 million dollars. The sale consisted predominantly of a share swap, in that Mr Smith received shares in MFS in lieu of a large cash lump sum payment. At the time of the sale in 2005, MFS Limited was on a strong growth trajectory fuelled by debt. With the onset of the Global Financial Crisis and the freezing of credit markets, MFS Limited went to wall and was placed into liquidation in July 2009. The result of all of this was that Mr Smith, who was a highly successful businessman, lost most of his fortune, estimated at over $300 million. This was all because of a failure to diversify.

Another example of the danger of having all of your eggs in the one basket is the problems those involved in the abalone industry now face. The recent ganglioneuritis virus is threatening to destroy the abalone industry in Australia. If the virus spreads, abalone quotas worth millions could be worthless if there is no abalone to catch.

Diversification is essential and the older you get, the more important it becomes to diversify your asset base. One common problem is that people invest in what they know and keep investing in what they know. For example, some people invest all their money into their business. Whilst this is not necessarily a bad thing, it does significantly increase the risks you face going forward. There is no investment that is immune from risk of some sort. By spreading your asset base you, in turn, minimise the risks you face. One investment may perform well in a particular environment. For example, a term deposit in periods of high interest rates, whilst another may struggle in the same environment, such as an investment property that has a large mortgage.

Diversification can take many forms. It could involve:

• Holding a portfolio of twenty to thirty direct Australian shares

• Investing in a managed fund with exposure to a number of markets and companies

• Holding investment properties in different states

• Having multiple business interests

• Having your income coming from multiple sources

The concept of diversification as a risk minimisation tool is crucial in building an investment portfolio.

Investing in accordance with your risk profile

We are all different, and there is no "one size fits all" approach. When considering where to invest, it is important that you consider how comfortable you are with the risk associated with a particular investment. Risk, in simple terms, is the chance that an investment will result in a loss. All investments have some degree of risk.

An assessment of your risk profile is used in financial planning to provide some indication as to the level of risk that you are comfortable with. Many people are risk averse, and this prevents them from actually making a start. We all have friends who keep money in a bank account, expecting it to be the foundation of a secure future. Let me share a secret with you: there has not been a person who has achieved financial security without taking on some risk. The more risk you take on the greater the potential upside or downside. We all take risks without realising it. For example, by buying our principal residence or having money put into superannuation by our employer.

As a general rule, our appetite for risk changes over time and is shaped by our life experiences. The younger we are, the greater our appetite to take on greater risk. At the age of thirty, I left a secure job in the legal profession, where my father and grandfather had worked for a combined period of sixty-five years. At the time I had no mortgage and no children. I resigned, retrained and moved into the financial services industry. I am not sure whether I would have made that same move if I was forty-five with three financially dependent children, a mortgage and a spouse who did not work.

Each generation is different in its views on risks and investing. For example, when I discussed investing with my grandparents their risk profile was very much shaped by their experiences during the depression and the various wars—World War Two, the Korean and Vietnam Wars—that occurred during their lifetime. As a consequence of these experiences, their investments were limited to the family home and term deposits.

Your appetite for risk is determined by a number of factors, including:

• Your expectation of the investment returns. This includes how a prolonged negative period of returns affects your particular situation. There are numerous studies, which highlight the fact that we all feel a negative return a lot more than a positive return

• Your understanding of investment markets

• Your past investment experience. For example, if your only experience in shares was in ABC Learning, where you lost all of your money, then you will generally be more reluctant to invest in the Australian share market than someone who bought one of the four banks (NAB, ANZ, CBA, WBC) fifteen years ago, and has done nothing since. The performance has been very different

• How short term fluctuations in the market affect you. For example, if you worry and cannot sleep at night if your investments go down in value, you should invest conservatively

• What time frame are you looking at investing for? As a general rule, the longer your investment time frame, the more aggressive you can be. For example, if you are twenty-five and you have some money in superannuation, it does not make sense to have this investment sitting in cash when you cannot touch this money until you are sixty

One of the main areas of problems for investors is where they invest in a manner which is inconsistent with their risk profile. For example, if you are ninety years of age and very conservative, it would be inappropriate for you to invest in a portfolio of speculative Asian mining shares. On the other hand, it might not. You might think the risk appropriate!

The risk and return trade-off

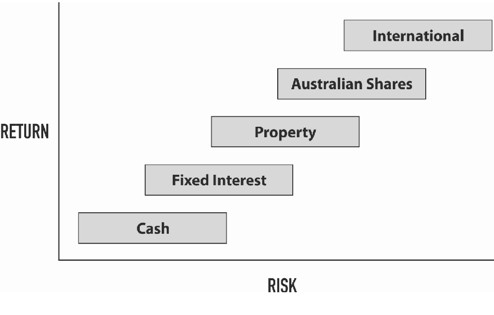

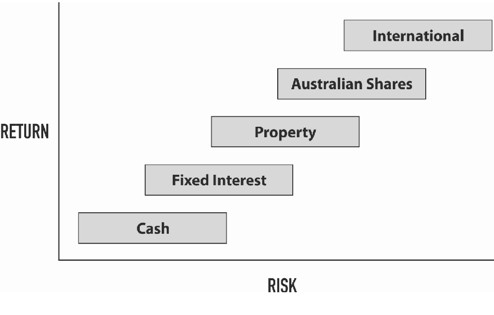

In simple terms, the risk/return trade off is based on the premise that the potential return rises with an increase in risk. Low levels of volatility and uncertainty, i.e. low risk, are associated with low potential returns, whereas high levels of uncertainty, i.e. high risk, are associated with high potential returns. According to this principle, the return will be higher if there is a higher risk of the capital being lost.

In broad terms this can be explained in the following diagram:

However, within each of the asset classes there are a number of sub-categories which need to be considered. For example, within the share market, a mining company that has yet to make a profit and is still undertaking exploratory drilling in Africa is a higher risk proposition than a company like Woolworths Limited. Within each type of investment, the risk/ return trade off can be very different.

In broad terms we can divide investments into:

Stable Asset Classes

• Cash—bank accounts / cash management accounts

• Fixed Interest—term deposits / income funds / income securities

Growth Asset Classes

• Property—listed property trusts / unlisted property trusts / investment properties principal residence

• Australian Shares

• International investments

In theory the risk/return trade off means that if you have two investors, Robert and Emma, for example, and they invest in different asset classes, they will have a different return from their investments. Imagine Robert keeps his money in cash for ten years and Emma invests hers in Australian shares, history will tell us that Emma will have ended up with a higher lump sum than Robert. This higher return is based on the premise that Emma took on a higher degree of risk than Robert, and will be rewarded accordingly. It is important to note that this is not always the case, and historical returns should not be used as a guide for future returns.

The importance of asset allocation

A person's asset allocation simply refers to the asset classes3 into which they have invested their monies. One of the major roles of a financial planner / investment adviser is to assist an investor with their asset allocation taking into account their appetite for risk. This depends on the factors outlined previously in the section titled "Investing in Accordance With Your Risk Profile".

3 The main asset classes are cash, fixed interest, property, Australian shares and international investments.

Studies have shown that up to 75-85 % of the actual return you receive depends on where you actually invest the money. In other words, the asset allocation you have is the major determiner of your portfolio return. The remainder of the return is influenced by factors, such as the timing of your investments and your individual investment selection.

This is a bold statement. Let us consider a person who buys an investment property. If there is a property boom, they will benefit with a gain, if there is a property crash they will suffer a loss. No matter how cheaply you buy the investment property your return is going to be largely determined by the property market in your area. If the market drops 50%, you are extremely unlikely to sell and make a gain of 50%.

During the recent bear market, from November 2007 onwards, at many social events I heard people make comments like "superannuation is a terrible investment'", "my adviser lost me 25% last year", "I am in a great superannuation fund, I made 5% last year", etc. All of these comments need analysis. Investments need to be scrutinised as to how they are working for the client. Superannuation is an investment structure. It is where the money is invested within that structure that determines the actual return to you.

Let us look at Frank's situation, where he had all of his superannuation invested in Australian shares in 2008 and his portfolio fell by 22%. On the surface, this is a terrible result and Frank would probably be quite disappointed with his return. However during the same period the Australian ASX 2004 Index fell by 43%, so Frank's portfolio actually outperformed the share market by 21% over this period. This is, of course, a small consolation to Frank because his investments decreased in value.

4 The Standard & Poor's Australian Stock Exchange 200 Index (S&P/ASX200 Index) represents the biggest 200 companies listed on the Australian share market.

During this period, if you had kept all of your money in cash, you would have been better off for 2008, but history will show that this is the worst strategy over the long term.

The simple solution which I have heard many times is: only invest when the market is going up and sell when it is about to go down. Unfortunately, predicting investment markets is notoriously difficult despite, all the media noise to the contrary.

Let us have a look at how some of the experts fared during this period:

Year End Forecasts for 2008

The Forecast:5

$AU: 90 US cents

Cash Rate 7.50%

ASX 200 up 8%

What Happened:

$AU: 70 US cents

Cash Rate 4.25%

ASX 200 down 41%

5 SMH / Age Economists Survey, Jan 6 2008 – "28 leading economists from the finance sector, business and academia"

As you can see from these predictions, if the economists can't get it right with their teams of highly qualified analysts assessing all of the relevant data, what chance does the average investor have? The secret is to work out a long-term strategic asset allocation and maintain it. It will, at times, be necessary to re-weight your asset allocation back to its original allocation. For example, if you decide the asset allocation of Australian shares should be 50% of the portfolio, and the performance of this asset class has been strong and may now represent 65% of the portfolio, every six to twelve months you would look at re-weighting the portfolio and reducing the Australian share exposure back to 50%. This would mean taking some profits from the Australian share component and re-investing this amongst the other asset classes.

The danger of not re-weighting your investment portfolio can be illustrated by referring to the listed property trust sector over the last 20 years. As part of a balanced portfolio an investor would normally have some exposure to listed property trusts, e.g. 20% of their portfolio. During the period from 1994 until 2007, listed property trusts delivered an annualised return of 12.31%. During this period you would meet with clients to discuss re-weighting their portfolio and you would hear many say, "Why would I do that? It is performing well", or "Are you mad? This is the best performing asset class".

Let's assume that you didn't re-weight your portfolio from the original 20% invested in listed property trusts in 1994. Your exposure to the listed property trust sector, as a percentage of your total investment portfolio, would have increased from 20% in 1994 to somewhere between 25-30% (depending on your asset allocation) in 2007. In the period from the 8th February 2007 when the sector peaked at 2,582 points, listed property trusts fell over 75% to 535 points on the 10th March 2009. Whilst the sector has recovered slightly, it still remains at levels below those of twenty years ago. What you saw as an investor was your listed property trust holdings increase significantly and then fall to the point where you would now have less than you originally invested in 1994. The moral of the story is re-weight your portfolio regularly to minimise the impact of such an event.

There is a real danger in changing asset classes in search of trying to time the markets and some studies show that 80-90% of investment returns come from less than 10% of the holding periods. For example, between 1981 and 2001 the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index6 returned 12.11% per annum. However this figure is a little misleading as removing the ten best performing months (i.e. ten months out of two hundred-and-forty months) produced returns of only 7.20%. In other words, a buy and hold strategy turned $100,000 into $1,071,816, whereas missing the ten best months turned the $100,000 into $423,815.

6 The All Ordinaries Accumulation Index represents the biggest 500 companies on the Australian share market. The performance figures take into account both dividends and capital growth

If we look at the period between 1991 and 2001, the results are very similar, with the return of 7.36% per annum. However taking out the ten best days out of this period (i.e. ten days out of three thousand, six-hundred and fifty days in total) reduced the return to 3.63%. In other words over a 10 year period less than 0.50% of the days produced 51% of the returns. These examples highlight the dangers of moving monies in and out of particular asset classes in an attempt to maximise your return.

When looking at the volatility of a particular investment, it is important to remember that where an investment falls in value you will always need to get a greater return to get back to your original position. For example, if you have $100 and your investment falls by 50%, you will have $50. If your investment rises by 50% (i.e. 50% of $50) you will have $75. Many people fall into the trap of thinking that, as my investment has fallen 50% and has now risen by 50%, I am back where I started. This is incorrect, as to rise from $50 to $100 you will need a gain of 100%.

As the great Warren Buffet once said, "Only buy something that you'd be perfectly happy to hold if the market shut down for ten years".

Useful websites

Contains a range of information about financial issues and decisions aimed at young people.