‘The Bren L.M.G. is the principal weapon of the infantry’ asserted the ‘Lecture for NCOs’ included in all wartime editions of the Bren manual, while rifles ‘will be needed to augment the fire of the L.M.G. when required in an emergency, for local protection, and especially for “sniping” single enemy’ (War Office 1942: 34). This unequivocal statement summarizes the importance placed on the Bren gun by the British Army. Every infantry section was to be built around a Bren gun, which would provide the main killing power of the section. Meanwhile, the riflemen were to serve as its ammunition bearers, provide local security, and if necessary act as replacement crew to replace casualties. Even the British 1937 Pattern Webbing worn by every rifleman, with its distinctive large twin ammunition pouches on the chest, was designed specifically to hold Bren magazines, as were the later 1944 and 1958 Patterns of Webbing.

While individual ammunition loads varied in different times and places, that set out in the 1944 edition of Infantry Training may serve as a typical example. It divided the section into two sub-units, the Rifle Group and the Bren Group. The seven-man rifle group was led by the section commander, usually a corporal, and consisted of:

• one NCO (Corporal) armed with a 9mm Sten gun and five magazines (150 rounds) plus two Mills bombs (No. 36 Grenades)

• six riflemen, each armed with a .303in Lee-Enfield No. 4 rifle and ten clips (50 rounds), plus two Bren magazines (60 rounds), a Mills bomb and either a shovel or a pickaxe to dig fighting positions.

The three-man Bren group was led by the section second-in-command, usually a lance-corporal, and consisted of:

• one NCO (Lance Corporal) armed with a .303in Lee-Enfield No. 4 rifle and ten clips (50 rounds), plus four Bren magazines (120 rounds) and a machete or a smatchet (a heavy-bladed knife) to clear brush

• one Bren No. 1 armed with a Bren LMG plus four Bren magazines (120 rounds) and the Bren tool wallet, containing small tools and spares for the gun

• one Bren No. 2 armed with a .303in Lee-Enfield No. 4 rifle and ten clips (50 rounds), plus five Bren magazines (150 rounds), a Mills bomb and a pickaxe, and the Bren spare-barrel carrier, containing the spare barrel, cleaning rod and other tools.

This gave each section a fairly impressive 25 Bren magazines, holding 750 rounds, plus another 250 rounds on the platoon truck. It is perhaps instructive to note that with the exception of the section leader, every man in the section carried more ammunition for the section Bren than for their own personal weapon. The No. 2 (and sometimes other members of the Bren team) carried a pair of utility pouches connected by a yoke, which were used to collect magazines from other members of the section; wherever possible, the Bren team used the magazines carried by their comrades first, and kept the magazines in their own pouches for an emergency. Unlike German machine-gunners, or British Lewis gunners during World War I, neither of the Bren numbers (crewmen) was routinely issued pistols, though they are sometimes seen carrying them in wartime photographs.

A Bren on a tripod mount during a pre-war exercise. Note that the crew are still wearing service dress and blancoed World War I-era 1908 Pattern webbing, which made no provision for carrying Bren magazines. (IWM Army Training 1938 2/20)

Anti-tank tactics

Canadian troops fighting off an attack by elements of 12. SS-Panzer-Division ‘Hitlerjugend’ shortly after D-Day. Although their rifle-calibre bullets wouldn’t penetrate armour, Brens were a key part of any anti-tank plan. Their fire would force tanks to ‘close up’ and would suppress any accompanying infantry. With their visibility drastically reduced, tank crews became vulnerable to tank-hunter teams armed with weapons such as the PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) visible here as a two-man team work their way around for a shot at the weaker side armour of this PzKpfw IV. As well as at the exposed commander, Bren gunners were taught to fire at a tank’s vision blocks, and some German tanks were fitted with dummy vision blocks to draw fire away from the real ones.

In addition to the Bren in each infantry section, an infantry battalion included a carrier platoon as part of its HQ company. This included 13 Universal Carriers (generally referred to as ‘Bren Gun Carriers’), in four sections of three vehicles each, plus a carrier for the platoon commander. Each of these carriers was armed with a Bren, and had a three-man crew, effectively providing a reserve of motorized Bren teams. The British Army manual on the carrier platoon reminded officers that ‘Carriers should not be used as tanks and sent into action with all their guns blazing. Rather, they should be regarded as armoured mobile L.M.Gs., their mobility and armour being used to move them quickly from one fire position to another’ (War Office 1943: 7).

Finally, Brens were held by other units for close defence or anti-aircraft protection. For example, each two-gun artillery section generally had a Bren for air defence, as did a proportion of logistics vehicles.

The 1937 edition of Infantry Training, issued a month before the first Bren gun left the factory, still shows a tactical model not much different from that of 1918. It depicts a platoon of specialized sections ‘equipped primarily for fire, as light machine gun sections, or for manoeuvre, as rifle sections’ (War Office 1937: 130). The next edition of the equivalent section of Infantry Training did not appear until March 1944, but many of the tactical changes it describes had been in place since the start of the war. Indeed, tactical practice with the Bren continued to evolve throughout the war, for example in the reduced emphasis placed on firing from a tripod.

| British scale of issue, personal weapons, 1944 | |||

| Infantry division | Armoured division | Airborne division | |

| Officers and men | 18,347 | 14,964 | 12,416 |

| Pistols and revolvers | 1,011 | 2,324 | 2,942 |

| Rifles | 11,254 | 6,689 | 7,171 |

| Sten guns | 6,525 | 6,204 | 6,504 |

| Bren guns | 1,262 | 1,376 | 966 |

| Vickers guns | 40 | 22 | 46 |

| PIATs | 436 | 302 | 392 |

A Bren gunner of The Royal Scots ready to give covering fire during the advance through the Netherlands. When the Bren was used as a one-man gun in the assault, the gunner could hold the carrying handle on the barrel with his front hand, or the folded bipod could be used as a grip, as shown here. Whichever grip was preferred, the Bren was capable of providing immediate fire support for its section even on the move. (IWM B 11758)

In the attack, the section could split into two and advance by bounds, the Bren group and rifle group taking it in turns to provide cover for the other as it advanced. Equally, in a platoon-level attack, two or more complete sections could cover each other in the same manner. ‘One group must always be either firing or down in a position from which fire can be instantly opened. Always have “one leg on the ground”’ (War Office 1944: 55). Where possible, the two elements would form a 90-degree angle with the enemy at the apex: ‘This enables the gun to give covering fire up to the last possible moment. It is of course an ideal which will not always be attained’ (War Office 1944: 55).

Even though this covering fire was not expected to inflict significant casualties – ‘if the enemy is dug in, covering fire seldom kills him’ (War Office 1944: 53) – it should suppress the enemy, allowing the rifle group to get close enough for a final short rush to clear the position with bayonets, grenades and automatic fire from the section leader’s Sten. ‘Every section is designed to provide its own covering fire within itself. It can, if necessary, rely on itself to get forward. This provision of covering fire is the primary task of the Bren gun in the attack; i.e. to help get the riflemen forward’ (War Office 1944: 53). When attacking a position, a good deal of stress was placed on trying to work a Bren around to the flank, and ideally positioning an additional Bren where it would be able to deliver enfilade fire on enemy troops as they fell back, having been driven out of their positions by the assault.

The cavalry Bren section

As well as the infantry section, the 1939 Bren manual also gives the organization for the six-man Bren section of the cavalry troop. The No. 1 carried the Bren in two sections (body and bipod in a bucket on the off side of the horse, barrel in a detachable case on the near side), while the No. 2 (who doubled as section leader) carried the spare barrel in a detachable case on the near side. (A rider mounts the horse from the left, or near side. The off side is therefore the right side, from the point of view of a rider sitting astride the horse.) Both men wore leather bandoliers similar to those used by other cavalrymen to carry rifle ammunition instead of webbing. However, these bandoliers held three Bren magazines in individual pockets. Each also had a pair of wallets (as the cavalry termed pouches mounted in front of the saddle) holding two magazines each, for a total of seven magazines per man.

The third and fourth men in the section were riflemen assigned to scouting and protective duties, while the fifth man was a rifleman assigned as a horse holder. The last rifleman led the section’s packhorse. This carried a pack saddle with the folded tripod above the horse’s spine in the centre, while on each side were four magazine carriers, each holding six magazines, for a total of 48 magazines on the packhorse.

This meant that the section had a total of 62 magazines, or 1,860 ready rounds for the Bren, two and a half times as much as an infantry section. However, each cavalry troop (approximately the equivalent of an infantry platoon) had only one Bren section, rather than three. Given that the Bren was coming into service just as the last fighting cavalry was being mechanized, it is unclear if this organization was actually used in practice. Certainly, it had disappeared by the time the Bren manual was revised in 1942.

Obviously, not all assaults could be delivered in such a methodical manner, and one of the great advantages of the Bren was that it could be used from its sling as a one-man assault weapon, delivering heavy fire to assault a position or mount a hasty counter-attack. A good example comes from the Victoria Cross citation of Australian Leslie Starcevich. His unit, 2/43rd Australian Infantry Battalion, was moving down a track through thickly wooded ground in Borneo in June 1945 when the Japanese attacked. According to his citation, gazetted 8 November 1945:

When the leading section came under fire from two enemy machine-gun posts and suffered casualties, Private Starcevich, who was a Bren gunner, moved forward and assaulted each post in turn. He rushed each post firing his Bren gun from the hip, killed five enemy and put the remaining occupants of the posts to flight.

The advance progressed until the section came under fire from two machine gun posts which halted the section temporarily. Private Starcevich again advanced fearlessly, firing his Bren gun from the hip and ignoring the hostile fire, captured both posts single handed, disposing of seven enemy.

In defence, a great deal depended on how much time was available for preparation. Earlier versions of Infantry Training set out a series of steps for fortifying a position, starting with simple slit trenches and working up by stages to a fully connected trench line with alternate and fall-back positions, but the 1944 edition assumes that such complex field works are unlikely to be generally needed in a mobile war.

Bren pits were normally dug in a dogleg shape, rather than the rectangular slit trench used by a pair of riflemen, so that the No. 2 was at right angles to the gun and could adjust the gas regulator easily. Rifle and Bren pits were not generally provided with overhead cover, to allow them to engage attacking aircraft. Bren guns were to be placed at the ends of the defended section, so that they could fire along the line of attack, rather than at right angles to it, as this would place more attackers in the gun’s beaten zone.

If there was time to create wire entanglements or lay mines, they needed to be covered by fire to be effective. When defending a window or loophole in a building, the Bren was to be kept well back from the opening so that its position was not obvious. Concealment was regarded as more important than fields of fire, which were often shorter than might be expected – ‘100 to 150 yds should suffice for both rifles and L.M.Gs.’ (War Office 1944: 112) – as the intention was for the defenders to hold their fire until it would have maximum effect, rather than give away their positions by firing as soon as the enemy was in sight: ‘Hold your fire until they are right close up and they should all be dead men’ (War Office 1944: 21).

At night, some or all of the Brens might be set up on fixed-line tripods to cover particular danger areas, such as gaps left in the wire to allow the defenders to send out patrols. Such guns were only to fire on orders, rather than give away their position by firing on their own initiative; the Japanese, in particular, often taunted Commonwealth troops at night to provoke a response. Of course, those who fell for this often found themselves on the receiving end of sniper fire or mortars. When time permitted, tripod legs might be weighted with sandbags to make them more stable, while boards (often from ‘Compo’ ration crates) were sometimes put under bipod legs on soft ground, to prevent the gun digging itself in as it fired.

A South African Bren gunner uses the cover of a doorway as his section advances through Florence, Italy, August 1944. (IWM NA 17636)

A well-conducted defence could inflict very significant casualties on an advancing enemy, as this account from Sergeant James Drake of 16th Durham Light Infantry indicates. His unit was dug in outside Sedjenane, Tunisia, in early 1943:

I had put a Bren on each flank, about fifty yards apart, so they could fire across our front in a crossfire. I gave strict instructions that nobody must fire a shot until I said so ... I waited until they had got within a hundred yards before I gave a fire order. I said ‘Right, lads, fire!’ Both the Brens started and we simply mowed them down. They all fell flat. The Brens kept going, and we were getting very little fire back. Some rounds splattering through the cactus trees. I says ‘Right, if you see any movement in anyone, put a bullet in him ... [The battle continued throughout the day, until] … By now, the light was fading. We’d been there since first thing that morning, and fired a lot of ammunition ... on both the Brens, the barrels were bent, including the two spares ... We had nothing more to fight them with. (Quoted in Thompson 2010: 293–94)

In a hasty defence, there might not be time to dig in, and Bren gunners might have to use the best natural cover available – hedge-lines, ditches, or folds in the ground.

Even the firepower of a single Bren could significantly slow an advancing enemy. Marine James Kelly, a Bren gunner of No. 41 (Royal Marine) Commando, became separated from his unit on D-Day, 6 June 1944, and an officer from another unit pushed him into line to help stem a German counter-attack:

Bren tripods

Three tripods were issued for the Bren, to allow the weapon to be used in a sustained-fire role. The initial Mk 1 tripod was based on the Czech-designed tripod for the Zb 26, and could be configured as an anti aircraft mount as well as a ground tripod. It consisted of a triangular frame with an adjustable leg at each point of the triangle, and weighed 29lb. A two-part anti-aircraft leg was stored inside the tubes forming the long sides of the triangle, one part in each. This could be removed and fixed together, then clipped to the front of the tripod to form a longer third leg, while the normal front leg pivoted upwards to form a high-angle mount for the gun. In an emergency, a Lee-Enfield rifle could be used instead of the AA leg, attaching to the tripod by the bayonet boss.

The Mk 2 tripod introduced in 1941 was significantly simpler, and omitted the features to convert it for anti-aircraft use. The Mk 2* tripod introduced in 1944 was a modification of the Mk 2 tripod for airborne use, with a folding rear quadrant to allow it to be folded into a more compact package.

A Mk I Bren on a Mk 2 tripod. Note that the rear elevating screw of the tripod attaches to the socket originally used for the butt handle. Unlike the more complex Mk 1 tripod (which looked almost identical when set up in a ground role), the Mk 2 tripod did not convert into an anti-aircraft mount. (Author)

The initial plan was that each Bren gun would be provided with a tripod, but in practice they were not often used, and the scale of issue was dropped to five per infantry company – one per rifle platoon, plus two more with the company HQ to be handed out as needed. Rather more than half the 126,000 Bren tripods produced were made in Canada, though the Mk 2* was only made in the UK.

He had binoculars and he was lying alongside me and it was very easy to comply with the fire control order that he gave me. A green field was stretching out in front of us and it came to a little hedgerow and a wooded area beyond it. ‘They’re all along that hedgerow’ he says. So all I had to use was the edge of the field and the bottom of the hedgerow as my aiming mark and it was quite easy to take aim at. So I opened up with a few long bursts.

Ammunition

The Bren used British .303in ammunition (7.7×56mm). This was originally adopted in 1888 as a black-powder-filled round with a round-nosed bullet, but had gone through a number of improvements. By the time that the Mk VII version was introduced in 1910 the .303 used a more powerful smokeless cordite propellant and had a ballistically superior pointed bullet, and the Mk VII continued in use until the round was replaced in service in the 1950s. Its rimmed design was perfectly adequate for bolt-action rifles or the belt-fed Vickers gun, but as we have seen, it was not ideal for magazine-fed automatic weapons such as the Bren. According to War Office figures, at 200yd the 174-grain (0.4oz or 11.3g) bullet would penetrate 58in of softwood, 18in of well-packed sandbags, or 14in of brick. Anyone unfortunate enough to be hit by such a bullet went down, and stayed down’ as one officer put it.

The more powerful Mk VIII ammunition, with a slightly heavier boat-tailed bullet and more powerful propellant charge, was intended to achieve maximum range from the Vickers MMG. It was not supposed to be used in rifles or Brens except in emergencies, as it caused significant barrel erosion in these weapons.

The rimless 7.62×51mm NATO round used in re-chambered Brens was 5mm (0.2in) shorter than the .303in but its muzzle velocity was only slightly lower with a bullet of the same weight, since the .303in cartridge case (originally designed for black powder) did not make the most efficient use of modern propellant.

Tracer was used against aircraft when available, but not generally against ground targets except on exercises. This was partly because while the belts for Vickers guns came factory loaded with 1-in-5 tracer, Bren magazines were usually filled in the field from the same boxes of .303in ball as the sections rifles. It was also partly because while tracer rounds let the gunner see where his rounds were going, they also made his own position very obvious.

Each Bren section was issued two rigid magazine boxes, each holding 12 magazines in metal clips. Although magazines were generally split out among the section members, the boxes provided extra protection in transit, and were sometimes seen in the front line, particularly when the section was on the defensive. (Author)

Although the Bren magazine theoretically held 30 rounds, it was normal practice to only load 28 or so; this reduced the magazine-spring pressure, and let the rounds feed more reliably. There were several proposals to pre-package Bren ammunition in disposable 14-round chargers, to allow faster reloading of magazines in the field. Trial versions of the chargers worked well, but the idea was never taken up as the Bren chargers could not be used to load rifles, complicating ammunition supply.

Loss and damage to magazines was a perennial problem, and there were various proposals to produce factory-loaded ‘expendable’ magazines for both the Bren and Sten. However, all foundered on the difficulties of producing something reliable and robust enough to stand up to field use and still cheap enough to be thrown away after use.

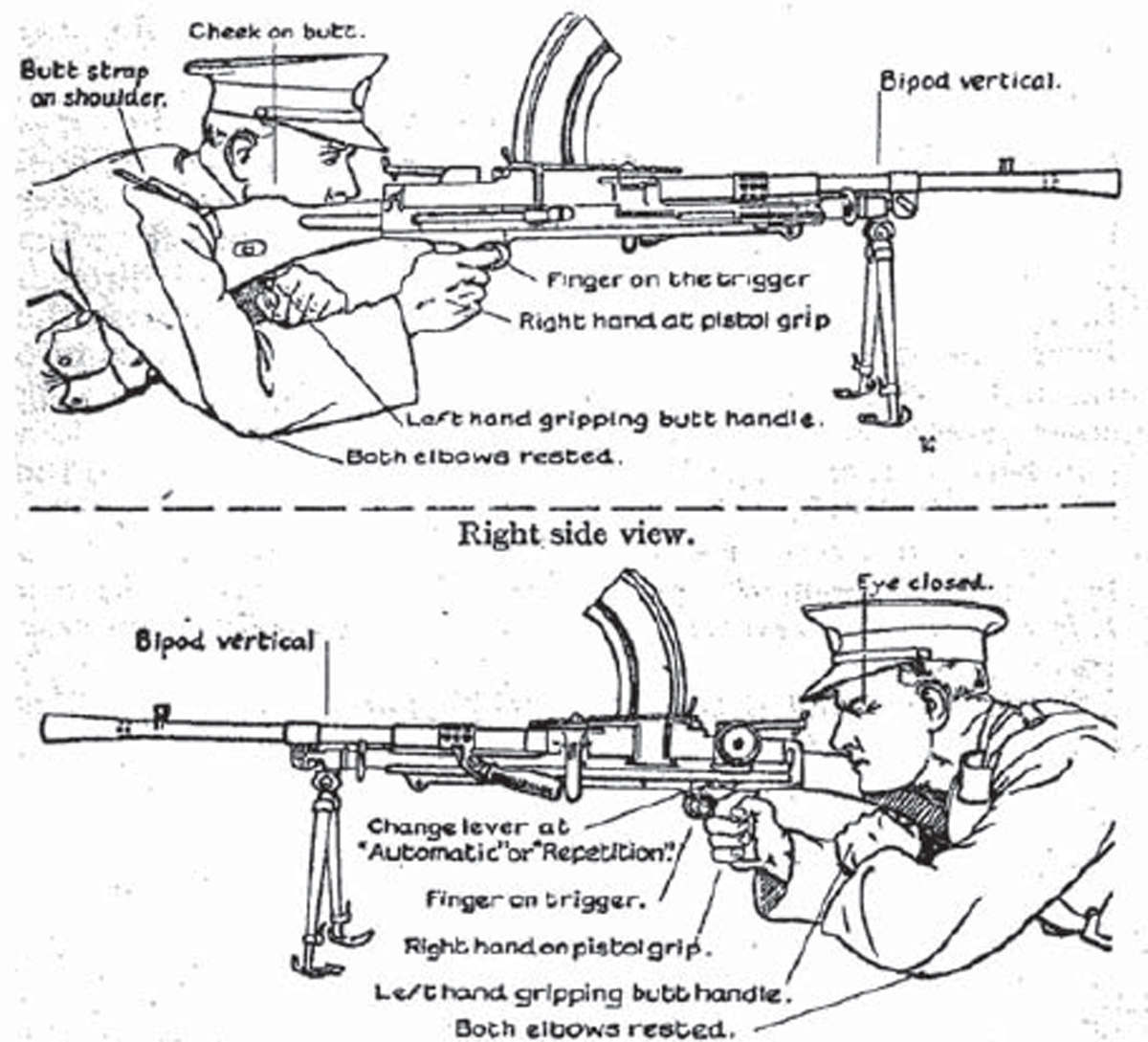

One of the neatly drawn illustrations from the 1939 Bren manual, showing the grip initially taught, with the left hand below the butt. This was found to be insufficiently stable, and amended to the grip shown in the photo opposite. (1939 manual, page 12)

You could see clumps of them moving about and I kept firing. Then it died down and I switched the gun to single rounds, which was the drill to do. You fired bursts when you had a good target to shoot at but the Bren was always used to confuse the enemy – that was what we were taught – so that the enemy wouldn’t know if it was a machine gun firing at them or a rifle. So you switched to single shots when you could and when I did it on this occasion it was just like being on the firing point in practice …

I think I was the only one who had a really clear field of fire so he kept supplying me with ammunition and loading the magazines for me and I kept up this steady rate of fire. But of course the Germans don’t take that lying down – if they’ve got a troublesome point they try to eliminate it as much as we would – so it wasn’t very long before I was getting mortared then and I realised I was the target. They came fairly close but I didn’t take much notice of them except on one occasion when the burst was really close ...

This went on for some time until:

It must have been late afternoon, we must have been in this battle right through the day, I didn’t know it was going to end but the order must have come through ‘Well, OK, you can pull out now’. I got told ‘keep up a steady rate of fire now because we’re running down the ammo’....

Kelly and the officer fell back, Kelly noting wryly: ‘We were running through an orchard towards a big wall at the end and even though I was encumbered by the Bren gun I still made the wall before he did’ (Quoted in Bailey 2009: 347–52).

A Canadian gunner showing the firing grip taught later, with the hand on the neck of the butt. This had replaced the previous grip well before the 1942 manual was printed. (IWM NA 11564)

Machine-gunners in World War I had been specialists, and the majority of infantrymen were not trained to use one. This was to change with the adoption of the Bren, and all wartime editions of the Bren manual state that ‘The light machine gun is the principal weapon of the infantry and every man will, therefore, be trained to use it’ (War Office 1939: 47). Given the relatively straightforward operation of the Bren, this was much easier to achieve than would have been the case with its much more complex predecessors, the Vickers and Lewis guns, both of which required considerable specialist training to use.

The Bren manual itself was structured as a series of lesson plans, covering the tactical use of the gun and selecting suitable positions as well as firing and maintaining the weapon. All infantrymen learned the basics of using the Bren, including live firing, during their initial recruit training. As a rule, only those actually assigned as No. 1 or No. 2 on the gun were taught the less common aspects, such as mounting the weapon on the tripod to cover fixed lines, and only they received the Bren gun proficiency badge worn on the sleeve of the battledress. That said, other men might have to take over the gun to replace casualties, and not every man carrying a Bren always had the proficiency badge, especially in units that had been in combat for some time.

Training in non-infantry units varied; armoured or artillery units often had Brens for anti-aircraft use, but not all their men were necessarily trained to use them. Lieutenant D’Arcy McCloughlin of the Royal Engineers, looking back on the retreat to Dunkirk, lamented: ‘We had had quite insufficient practice. The idea of shooting from a Bren, using tracer and taking on low-flying aircraft, had never occurred to anyone and none of us had been trained in it’ (Quoted in Levine 2010: 45).

An Australian Bren gunner firing at Japanese positions on Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, April 1945. He has fastened the tool wallet (usually carried on the webbing) to the butt of his Bren. (AWM 091023)

Firing the Bren

To load the Bren, the gunner (or No. 2) slid open the magazine-well cover, placed the front edge of the magazine under the lip of the magazine well, and pulled the body of the magazine back until it locked in place. Magazines held 30 rounds in theory, but the rimmed .303in rounds did not always feed well, and the later editions of the manual recommended only loading 28 rounds per magazine. It was very important to ensure that the cartridges were not loaded into the magazine ‘rim behind rim’, as this would cause a stoppage. Once the magazine was in place, the gunner reached forward and pulled back the cocking handle to chamber the first round.

The Bren’s top-mounted magazine meant that sights were offset to the left side of the weapon; there was no sensible way to fire the weapon from the left shoulder as one could with a rifle. Sights were adjusted for range by rotating the drum of the back sight (Mk I Bren) or by sliding the adjuster on the ladder-type back sight (later versions) until it corresponded to the gunner’s estimate of range to target. If time allowed when defending fixed positions, ranges might be paced out and marked with piles of stones. (Sights need to be adjusted because gravity and air resistance mean that bullets actually travel in a parabola, rather than a straight line. Adjusting the sights changes the point of aim to compensate for this.)

The Bren had a three-position safety catch, marked ‘S’ (Safe), ‘R’ (for ‘Rounds’, i.e. semi-automatic) and ‘A’ (for full-automatic fire). The single-shot ‘R’ setting was used to allow the Bren to fire without giving away the presence of a machine gun until the enemy were within good killing range. However, the normal practice in combat was to use 4–5-round bursts; shorter bursts made it difficult to observe the impact of rounds, while longer bursts wasted ammunition and overheated the barrel too quickly.

Cartridge cases were ejected downwards, which was generally a positive feature in an infantry gun; the flicker of cases ejected upwards or sideways from weapons such as the Lewis gun drew the eye, and could give away the gunner’s position. It was less advantageous in a vehicle pintle mount, where the ejected cartridges rained down on the rest of the crew. Drivers of Daimler Dingo scout cars seemed particularly likely to receive red-hot spent shell cases down the back of the neck, and several commented to the effect that this could be something of a distraction! A canvas bag to catch spent cases was designed, but not always issued or used.

Recoil was not too bad, and generally less than the Lee-Enfield rifle, because of the weight of the gun and because the gas system tapped off some of the energy. However, the manual emphasized the importance of a good firm grip, especially when firing from the hip.

The gunner could easily develop a kind of ‘tunnel vision’, focusing on the limited field of view visible through the sights and the No. 2 was fully occupied keeping the gun supplied with fresh magazines or reloading empty magazines from bandoliers of loose rounds. It was therefore the job of the lance-corporal commanding the Bren team to spot new targets for the gun to engage, and keep abreast of the flow of battle to recognize when the team should move forward to a new position or fall back.

After firing ten magazines at the ‘Rapid Rate’ of four magazines per minute, the barrel would start to overheat and need changing. This would normally be done by the No. 2, by disengaging the barrel-nut catch, rotating the barrel nut and pushing forward the carrying handle to remove the barrel. The spare barrel carried by the No. 2 would then be locked into place, and the gun could continue firing while the original barrel was laid aside to cool. If there was a stream or puddle nearby, the hot barrel would be laid in this; even wet grass significantly helped to cool the barrel.

This quick and easy barrel change was one of the great strengths of the Bren. A well-trained crew could change barrels in 6–8 seconds, and maintain sustained fire almost without interruption, a very significant advantage over fixed-barrel weapons like the US BAR. The well-designed carrying handle fitted to the barrel of the Bren also had the enormous advantage that the No. 2 could handle the hot barrel without any special precautions to avoid burning his hands, an almost unique feature on guns of the period. For example, barrel changes on the German MG 34 and MG 42 series required the gunner to use a thick and clumsy felt pad to hold the hot barrel, while even the postwar US M60 needed the gunner to use an asbestos glove for barrel changes.

Since repeated stripping and reassembly, cocking and dry-firing led to wear and poor fit of the working parts of the gun, old and worn-out guns were deactivated and converted into ‘Drill Purpose’ guns for recruit training, clearly marked as ‘DP’ in white paint. The 1942 edition of the manual also found it necessary to urge stripping and reassembly be limited to that necessary for cleaning, and to prohibit practising stripping and assembly ‘against the clock’, though this prohibition was not always obeyed.

Of course, men did not always remember their training perfectly amid the adrenalin of combat. Lieutenant Tony Pawson of 10th Rifle Brigade recalls ambushing a German motorcycle and side-car in Tunisia in early 1943:

I had a Bren gun. Instead of lying down and firing in short bursts, I was so excited I fired the whole magazine standing up from the hip. I planned to fire at the motorcycle to prevent it getting away, but missed. One of the Germans had a go at me. I was stupidly still standing up. Despite all my Bren gun training I couldn’t understand why it wasn’t firing – of course the magazine was empty and I hadn’t got another magazine handy. (Quoted in Thompson 2010: 277–78)

Other men went to the opposite extreme, focusing on the drills they had practised no matter what was going on around them. Sergeant James Bellows of 1st Royal Hampshire remembered that on D-Day:

I witnessed something that you only expect to see in training. These two men were firing with their Bren gun ... the gun jammed. They both slithered to the bottom of the hole they were in. With a Bren gun you’ve got a wallet with various parts and various tools for various stoppages, and they opened the wallet, as on par for parade, took out their tools, stripped their gun, cleared their fault, put it back together again, closed the wallet, even put the little straps through their brass links, then went back up the hill and carried on firing. (Quoted in Bailey 2009: 319)

Most men, of course, fell somewhere between the two extremes.

Two members of the Home Guard with a Bren and a Thompson SMG, in December 1940. A Home Guard unit would be very lucky indeed to receive a Bren rather than a Lewis or BAR; one cannot help suspecting that the Bren has been ‘loaned’ for this propaganda shoot. (IWM H 5839)

The Bren was a relatively new and recently adopted weapon when war broke out in 1939, and the British Army had not yet fully re-equipped. As it was, almost every available Bren went to France with the BEF. These guns saw heavy use against the attacking German forces initially. Once the Allied front had collapsed, however, and the retreating British units were ordered to abandon and burn their vehicles, many Brens were left behind along with other heavy equipment. Some units did retain their Brens during the retreat to Dunkirk, but most were more concerned with avoiding German troops and carrying wounded comrades, and did not. Units that had experienced fouling problems (often made worse by lack of cleaning during the chaotic conditions of the retreat) were particularly likely to abandon their Brens. Some were even destroyed unissued, as the BEF blew up or burnt its supply dumps as it retreated.

When the Army took stock after the evacuation, it discovered that there were only 2,300 Bren guns in the country, only enough to equip about two divisions. A plan was immediately put into place to increase production of the Bren by simplifying it, and a contingency plan developed for a simple-to-produce LMG (the Besal) as a stopgap in case of invasion, but both of these would take time to bear fruit. In the meantime, the government issued thousands of old obsolete Lewis guns (often the aircraft version, without the distinctive aluminium barrel shroud) and purchased 25,000 Browning Automatic Rifles and 40,000 Lewis guns from the United States. Both the latter were surplus US Army weapons chambered for the US .30-06 cartridge, rather than the .303in conversion of the BAR tested at the same time as the Bren or the World War I British .303in version of the Lewis. Almost all of these weapons went to the Home Guard, which at least meant that all of the Brens produced could be issued to the Army.

Brens for the French Resistance

The Bren’s light weight and the fact that it could be carried by a single man made it ideal for the French Resistance, and relatively large numbers were supplied by air drop. Very approximately, one in ten of the weapons supplied to the Resistance during the war were Brens, with the remainder being split roughly evenly between rifles and SMGs, plus a small number of pistols and anti-tank weapons such as the American Bazooka and British PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank).

A member of the French Forces of the Interior with a British-supplied Bren, Châteaudun, France, 1944. (Cody Images)

Some arms were dropped to other Resistance movements such as the various Yugoslav partisan groups, but simple distance restricted this until airfields in Italy and the Mediterranean became available, and in many cases, the RAF’s Bomber Command saw arms drops as an unwelcome distraction from what it regarded as its primary mission – bombing Germany’s productive capacity to rubble.

Bizarrely, some of the 7.92mm Brens of the type made by Inglis for the Nationalist Chinese, but without the Chinese markings, were apparently passed to the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). The idea was presumably that since they used the standard German rifle round, Resistance groups equipped with them would be able to use captured ammunition. However, this would equally have meant that they couldn’t use other ammunition supplies provided by SOE, which would seem to outweigh this, and it is not clear how many, if any, of these guns were actually dropped into Occupied Europe.

Since the BEF in France had received first priority for the issue of the new Brens, British units in the Middle East had generally not been issued with the newer guns when the war broke out, and were often still soldiering on with rather elderly Lewis guns. Shortages of the Bren continued into the fighting in the Western Desert in 1941–42; most British units had their full complement of Bren guns, but Indian Army units (including their British battalions) were still equipped with the serviceable but inferior Vickers-Berthier, while Captain Vernon Northwood, an officer serving with 2/28th Australian Infantry Battalion, 9th Australian Division, talks of having to use captured Italian Breda LMGs (Thompson 2010: 36). Photographs of vehicles (especially Long Range Desert Group trucks) from this period often show a variety of machine guns such as the Vickers K, scrounged from a variety of sources including wrecked aircraft.

A Bren gunner in North Africa, June 1943. Using the 100-round AA drum in the ground role like this was unusual, as it blocked the normal sights. One suspects it is simple posing for the camera, rather than a real intention to use the weapon like this. (IWM NA 3345)

Lend-Lease Brens

The Red Army probably do not immediately leap to mind as users of the Bren gun, and Western readers are generally used to thinking of Lend-Lease aid as something Britain received, rather than something that Britain provided to other countries. However, after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Britain dispatched whatever aid could be spared via convoys to the Arctic port of Murmansk. This included everything from food and medical supplies to fighter aircraft, although it did not include significant quantities of small arms since the Soviets could produce enough of these themselves. It did, however, include roughly 7,000 Universal Carriers, Valentine and Matilda tanks. Each vehicle was shipped with full stowed equipment, including a Bren gun per vehicle. These guns were often passed on as infantry weapons if the vehicle itself was disabled or worn out.

For propaganda reasons, the Soviets were reluctant to admit that they needed aid from countries they despised for ideological reasons, and such equipment was rarely referred to in official Soviet histories, though photographs do survive.

The desert was a challenging environment for any weapon, with its heat and constant sand and grit. Weapons could not be oiled after cleaning, as the ever-present dust quickly turned any lubricant left on the gun into a gritty paste that wore away working parts. Fortunately, the Bren had been designed with the mud of World War I trenches in mind, and apertures where dust could get into the mechanism were minimized; there was even a sliding cover to close off the magazine well when no magazine was fitted. This was a significant improvement on the Lewis gun, where the open bottoms of the pan magazines meant the cartridges tended to pick up grit, which they then carried into the weapon’s mechanism. As a result, though careful cleaning was needed, there were no serious reliability problems with the Bren.

By the end of 1942, increased production in Britain, Canada and Australia meant that the shortages had disappeared, and many Indian Army units in North Africa found themselves receiving Brens to replace Vickers-Berthiers lost in combat. Most welcomed it as an improvement, since it was lighter and easier to carry. By the Tunisian campaign of 1943, almost all units were equipped with Brens, though other weapons were still occasionally seen.

Meanwhile, troops in the Far East had also enjoyed a relatively low priority for the newest weapons up to 1940, despite repeated requests. In fairness, the weapons were in limited supply, and it is difficult to fault the British government for giving priority to theatres where fighting was actually taking place.

The Japanese invasion of Malaya and Burma in late 1941 resulted in sweeping victories against relatively ill-prepared British and Indian Army units, and in more lost equipment and weapons. By the end of the retreat from Burma, 17th Indian Infantry Division had only 56 functioning Bren guns left, for example, compared to the thousand-plus it should have had according to tables of equipment.

Umrao Singh’s VC

Umrao Singh’s Victoria Cross action, Kaladan, December 1944. Havildar (Sergeant) Singh was in command of a 3.7in mountain-howitzer section that endured sustained artillery bombardment before being repeatedly attacked by Japanese infantry. Wounded in the first attack, and with most of his crew dead, Singh used his gun’s Bren over the gun shield to hold off the Japanese at a range of less than 5yd. When the ammunition ran out, he beat several Japanese to death in hand-to-hand combat before collapsing, with seven separate shrapnel, bullet and bayonet wounds on his body. Amazingly, Havildar Singh was found unconscious but alive when the position was recaptured, surrounded by ten dead Japanese.

As the Japanese pushed in on the borders of British India, the forces fighting them were largely equipped with Indian-manufactured Vickers-Berthiers. More and more Brens arrived from Britain, however, both with newly arrived units and as replacements for weapons lost or worn out in the fighting. In 1942, the factory at Ishapore switched over from producing Vickers-Berthiers to producing Brens, and the latter weapon slowly came to predominate in the Far East theatre, too.

The Bren’s portability was particularly well-suited to the Far East theatre, where jungle and swamp terrain meant that much of the fighting relied on what the infantry could carry themselves, and its powerful rounds penetrated vegetation cover better than the smaller-calibre rounds used by the Japanese. The Australians in particular took to the Bren, boosting numbers deployed and often using it from its sling as they advanced, so that it operated almost as a heavy automatic rifle rather than a machine gun.

An Australian Bren gunner accepts a cigarette from an American after their forces in New Guinea linked up in February 1944. The sling has been shortened to hold the gun by the hip, ready for immediate use. (AWM 070318)

A Sikh Bren gunner from an Indian unit of Eighth Army in Italy, December 1943. Note the use of paint to camouflage the Bren’s highly visible upright magazine. (IWM NA 9787)

When the Allied invasion of Occupied Europe finally came – first through the misnamed ‘soft underbelly’ of Italy in 1943, and then via Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944 – the Bren was once again in the forefront. As well as its primary role as a section gun, it was also the primary British light AA weapon, and served as a pintle-mount weapon on a wide variety of armoured vehicles.

The excellent sustained-fire capability of the Bren, rapidly deployed and available down to section level, was a key factor in maintaining the firepower of British infantry units, which were still equipped with bolt-action rifles at a time when their American equivalents now had semi-automatic Garand rifles, and their German opponents were increasingly equipped with the first selective-fire assault rifles.

Another advantage of the Bren became apparent in the bitter winter of 1944/45, when Commonwealth soldiers found that their Bren guns remained operational even when the water in the cooling jackets of their heavier Vickers guns froze solid.

Once the war was over, the costs of rebuilding a country damaged by bombing and worn out by six years of war meant that there was little money available for new weapons; even basic foods were still rationed into the early 1950s. This was particularly the case for the Bren, which was felt to have performed relatively effectively in its role, and was well-regarded by the troops.

The Bren’s relative simplicity was a significant advantage during the National Service era, as the majority of British troops during this period were conscripts, serving for relatively short two-year enlistments. As well as the Korean War, these young conscripts took part in a number of smaller ‘end of empire’ military operations, including the Malayan Emergency (1948–50), the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952–60), the Suez Crisis of 1956 and the Cyprus Emergency of 1956–60. The last National Servicemen were enlisted in December 1960.

Learning to use the Bren was a common memory of National Servicemen in the Army; a lecture on the weapon even forms part of the comedy Carry On Sergeant, the first in a series of films which became a minor British institution of the period themselves.

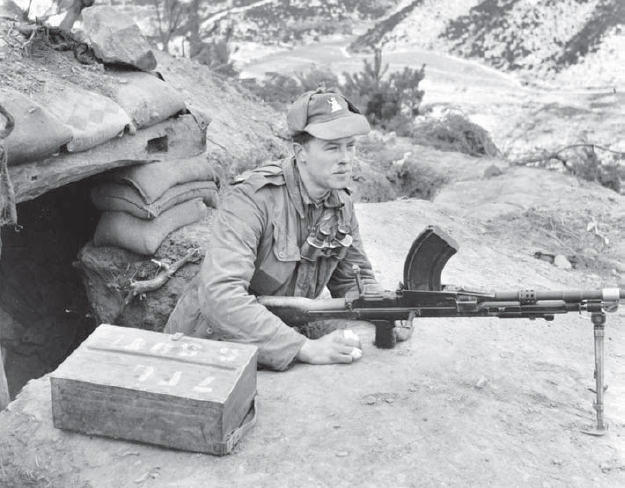

A Bren gunner scans the Korean hillside opposite his dugout, early 1952. The box by his side holds 12 Bren magazines. Note the offset handle that allowed two boxes to be carried back-to-back in the same hand. (AWM LEEJ0229)

A Bren group of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, Korea, January 1951. (Cody Images)

The Japanese had ruled the Korean peninsula since before World War II, and with their defeat, it had been divided between US and Soviet occupation forces along the 38th Parallel. This quickly became a political border as well as an administrative one, with a communist regime installed in the north. North Korean troops invaded the South in June 1950, in the first major incidents in the Cold War. Their initial successes against the unprepared defending forces were quickly reversed, but when the North Koreans were driven back across the 38th Parallel, the communist People’s Republic of China intervened on the North Korean side, and the United Nations forces were forced back in turn. The ferocious defence of the Imjin River line by the British 29th Infantry Brigade managed to halt the Chinese offensive, however, and the war bogged down into positional fighting.

The British troops deployed as part of the UN-sponsored ‘Free World Forces’ were still largely equipped with World War II-era personal weapons, though now supported by jet aircraft and Centurion tanks. In fairness, their communist opponents were in the same position, being armed largely with Soviet small arms of the same vintage. Once again, the Bren performed well, with the main difficulty being keeping the weapons operational in the bitter sub-zero conditions of the Korean winter. Instructions were issued to keep the weapons free of snow, which could build up to form ice and jam the weapons. In extremely low temperatures, gun oil froze, and Bren guns were to be cleaned with petrol to remove all traces of it, then reassembled ‘dry’.

As an indication of how important Brens were to British units, Chinese troops fighting against them were told to identify Bren gunners and concentrate fire on them whenever possible, since taking the Bren out of action would seriously reduce the British section’s firepower. During 1st Gloucestershire Regiment’s stand on the Imjin River, for example, so many Brens had been damaged by incoming fire that Regimental Sergeant-Major Jack Hobbs was forced to dismantle damaged Bren guns in order to assemble working weapons from the undamaged parts of each (Salmon 2009: 203). In response, some British units tried to camouflage the Bren’s distinctive upright magazine with paint or sacking, to little avail.

Ironically, some British units found themselves capturing examples of Brens supplied to the Chinese Nationalist forces for use against the Japanese during World War II, and now being used by the communists who had defeated the Nationalists.

An Australian Bren gunner waiting to go out on patrol in Korea, May 1953. He has stuffed spare magazines into his pockets, rather than wearing webbing. (AWM HOBJ4271)

By the early 1950s, the World War II-era personal weapons of the British were looking decidedly out of date. The Bren was still relatively well-regarded, however, and it was entirely possible that a re-chambered version might have soldiered on as the section LMG alongside riflemen carrying the radical bullpup EM-2, and with the Bren-derived Taden gun in the sustained-fire role.

In fact, American pressure led to the adoption in 1954 of the 7.62mm NATO cartridge, and a version of the Belgian FN FAL, known as the L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle in British service. However, this was far from the end of the line for the Bren. Re-chambering existing weapons for the new calibre was relatively straightforward, and the resulting guns were even able to use the same magazines as the SLR in an emergency. Even the 1958 Pattern Webbing designed to carry magazines for the new rifle was still capable of taking the magazines of the re-chambered Brens.3

The Army, however, wanted a true all-round machine gun – something along the lines of the German MG 42 – which would be able to fulfil all machine-gun roles, including those such as the vehicle co-axial role that the Bren did not fill particularly well. The specification for the replacement gun obviously owed a great deal to experience with the Bren, such as the requirement for a quick barrel change without the need for special pads or gauntlets to handle the hot barrel. However, it also included a requirement for belt feed, from a disintegrating link belt of the sort used on the new US M60 machine gun.4

The Royal Ordnance factory at Enfield submitted a Bren-derived belt-fed weapon – the X11 gun – as a response to this specification. Competitive tests compared this with another belt-fed Bren derivative from BSA (the X16), the US M60, the Belgian FN MAG, the French AA52, the Danish Madsen-Setter and the Swiss SIG MG 55-2 and MG 55-3. The FN MAG was considered to have done best, while X11 came second. After further tests, the FN MAG was adopted as the L7A1 GPMG in 1958.

It might perhaps have been comforting to the Royal Ordnance team to know that the last descendant of the Bren had been beaten only by a truly world-class gun; at the time of writing, the L7A1 is still in front-line service with the British Army, having served well in all theatres for 55 years without significant changes. It is also in use with dozens of other armies and is currently being adopted by the US Army as the M240, an astonishing achievement for a 60-year-old weapon.

Unlike both the Canadian and Australian forces, the British Army did not buy any of the heavy-barrel SAW version of the FN FAL. It was felt that it was too light for the role and would not be able to maintain any real volume of sustained fire, an assessment that proved true when the weapons saw combat. Instead, the British chose to retain the re-chambered Bren in a limited number of roles, designated as ‘Light Machine Gun’ as opposed to the L7 ‘General Purpose Machine Gun’.

Royal Marines in Aden, 1962. The 7.62×51mm version of the Bren served alongside the newly introduced L1A1 SLR until replaced by the belt-fed GPMG. (Royal Marines Museum Collection – Crown Copyright MOD 1962)

As part of Britain’s withdrawal from empire, the British colonies of Malaya and British Borneo were merged to form the Federation of Malaysia in 1963. However, the Indonesian government under the Nationalist President Sukarno hoped that if those territories could be destabilized, they could be merged into the Indonesian south of the island, or at least detached from British influence and converted into client states. Indonesian irregular forces began infiltrating across the long jungle border between the two countries to attack targets such as police stations. Regular Indonesian troops followed, as the situation worsened.

The first British troops involved were armed with the relatively new SLRs and Bren guns (in 7.62mm NATO), as the new L7A1 GPMG was not yet available in sufficient numbers, although this would change as the campaign progressed. Interestingly, many of the units involved believed that Brens were better weapons for these jungle operations, and continued to use them even once sufficient GPMGs were available. The main drawback of the GPMG was that the belted ammunition could tangle on vegetation, or could give away a patrol’s position when the bullets clinked against each other or caught the light.

The Falklands, 1982

The Bren’s last significant combat use was in the Falklands. The Royal Marines had retained a number of L4A4 versions, re-chambered for the 7.62×51mm NATO round, and deployed these to augment the firepower of their rifle sections’ GPMGs. Here we see men from 42 Commando assaulting the dug-in Argentine positions on Mount Harriet, as the British forces close on Port Stanley. During the heavy fighting, the L4A4’s ability to use magazines from both British SLRs and Argentine FN FAL rifles proved very useful, as the gunners were able to continue firing even after they had used up their initial ammunition loads, without calling on the limited amount of spare belted ammunition carried for the GPMGs.

The Bren was also lighter, and could be fired more easily from the hip, allowing it to get into action more quickly. This was a key advantage in short-range jungle encounters that characterized the confrontation, and where the GPMG’s primary advantage of better sustained fire was rarely relevant.

Although generally replaced by the L7A1 GPMG, the L4A4 version of the Bren continued in use in a limited range of applications. They were commonly seen in photographs of Royal Marines deployed to Norway during annual exercises to secure NATO’s northern flank, often camouflaged with white tape to break up the weapon’s outline, especially the prominent vertical magazine. The Royal Marines found that the enclosed magazines of the L4A4 fed more reliably in Arctic conditions than the ammunition belts of the GPMG; these tended to pick up snow, which then froze the belt solid.

The L4A4 also remained in service as a pintle-mount weapon on vehicles such as the FV 433 Abbot 105mm self-propelled gun, though in practice such weapons were rarely mounted on the vehicles they were theoretically assigned to. One soldier serving in a field-artillery regiment in 1978 commented: ‘On occasion, these guns would be let out of the armoury for us to look at. On even rarer occasions they were taken on exercise’ (Khan 2009: 52). It turned out that he was the only man in the troop who knew how to strip the weapon, and that was only because he had been trained on one as a cadet before joining the Army.

Royal Marines during a deployment to Northern Norway in January 1980. Note the use of white tape to break up the outline of the L4A4 and SLR. (Royal Marines Museum Collection – Crown Copyright MOD1980)

Royal Marines of No. 42 Commando in Port Stanley, June 1982. The front man carries an L4A4 while the rear man carries an L7A1 GPMG, the weapon that replaced the Bren in general service. (Royal Marines Museum Collection – Crown Copyright MOD1982)

The Argentinian Junta launched an invasion of the Falkland Islands (a British territory in the South Atlantic) in 1982, at least partially to use the ensuing patriotic fervour as a distraction from their country’s ongoing economic problems and the regime’s human-rights abuses. They had gambled that Britain would be unable to mount a counter-invasion over such a long distance. While this proved to be a miscalculation, it was very obvious to the commanders of the British Task Force dispatched to liberate the islands that the logistics of an amphibious operation 8,000 miles from home would mean that the infantry units involved would have little of the support they would have expected in the European war they had trained for.

The Royal Marines in particular therefore opted to beef up the firepower of their infantry sections by issuing each with an L4A4 light machine gun in addition to the GPMG it would usually have. The Parachute Regiment also felt that more supporting fire would be required, but appears to have obtained additional GPMGs instead. In the case of the Royal Marines, since the other members of the section were already carrying ammunition for the section GPMG, extra rations and mortar ammunition, there was little possibility of them carrying additional magazines for the LMG on the long cross-country ‘yomps’ that characterized the war. Most L4A4 gunners, therefore, had only a dozen or so magazines for the gun, split between themselves and their No. 2, though they could also use magazines from other riflemen in their section.

A Bren gunner of The Royal Sussex Regiment in Burma, November 1944. He is carrying his spare magazines in what appears to be a ’37-Pattern binoculars pouch, unfastened for easy access. The rectangular pouch behind his hip is the Bren’s tool wallet. (IWM SE 729)

Bren accessories

A large number of accessories were issued for the Bren at various points, but the most important and commonly encountered are described here. Each Bren team was issued a Bren Wallet and Bren Holdall. Patterns varied slightly between manufacturers and through time, but all were basically similar.

The Bren Wallet was a folding canvas roll carried by the No. 1 on his webbing, and contained: a combination tool to disassemble the gun; a pull-through to oil the barrel; an oil can to lubricate the gun; and a spare-parts tin holding common spares, for example a spare return spring.

The Bren Holdall was carried on a shoulder sling by the No. 2, and was commonly called the ‘spare barrel carrier’ since the main compartment held the spare barrel and cylinder-cleaning rod. Another pocket held the Bren Wallet described above when not in use. Other pockets carried: a bottle of ‘cold weather’ oil; an oil bottle of graphited grease; a mop, wire brush and magazine brush for attachment to the cylinder rod; and a fouling tool. In combat, the No. 2 often left the holdall with the unit transport, and carried just the spare barrel tucked under the flap of the pack.

Other commonly issued items were rigid magazine boxes, each holding 12 30-round .303in magazines in individual clips. Magazines were kept in them at any time when the unit was not in combat, which prevented damage to the feed lips of the magazines as they knocked around in web pouches. The handles of these magazine boxes were offset to one edge, so a pair could be carried easily in one hand by holding them back-to-back so both handles were together. An almost identical box was produced for 7.62mm NATO magazines; the original boxes could not be used with the new magazines, as they were much less sharply curved. As a consequence, the box for 7.62mm magazines was much shallower than the .303in version. A magazine filler tool was theoretically issued, though they were not always available. Magazines could be filled without it, but it speeded up the laborious task of filling the large number needed in combat. Finally, a sturdy wooden packing case with rope handles (‘Chest, Bren’) was used to store and ship the weapon itself.

The Bren Holdall (left) with the spare barrel, and the tool wallet (right) unrolled to show the contents, including the cleaning rod, spare-parts tin, combination tool, pull-through to clean the barrel and a rectangular oil bottle respectively. The tool wallet secured with webbing tabs when rolled, and was worn on the No. 1’s webbing in action, or carried in the large external pocket of the holdall when out of the line. (Author)

They could (and did) also use captured Argentine magazines – by a happy coincidence, the change to a larger magazine-locking lug design made as part of the changes between the original FN FAL and the British SLR meant that British soldiers could use Argentine FN FAL magazines in their SLRs, but Argentine FALs could not use British magazines. Given that each section already had a GPMG, and ammunition for the LMGs was limited, the L4A4s were mostly used as heavy automatic rifles, rather than as section light machine guns proper.

The change from the 7.62mm SLR to the 5.56mm L85 (SA-80) assault rifle in the mid- to late 1980s marked the effective end of the Bren’s long career with the British Army. It could no longer use the same ammunition as the rest of the infantry section, and would no longer be needed as each infantry section now had two L86 Light Support Weapons (LSW). The LSW was a version of the L85 with a longer, heavier barrel and a bipod, and was expected to be able to perform the same role as the ageing L4A4, at a lower weight.

In fact, the L86 proved inadequate in the light-support role, perhaps unsurprisingly since suggestions that it should have a quick-change barrel and fire from an open bolt to aid cooling had both been rejected since they would reduce commonality with the baseline L85 rifle, a major selling point of the design. The L86 LSW was therefore partly replaced by the FN Minimi, a more conventional 5.56mm SAW already in service with the US Army, although some were retained in the rifle squad to provide accurate semi-automatic fire or short bursts of full-automatic fire at extended ranges.

A few Brens soldiered on through the 1st Gulf War in 1990–91, as pintle-mount weapons on a few second-echelon vehicles. However, the author has not been able to find evidence that any of these weapons were actually used in action. They were largely withdrawn from service during the rationalization of equipment following the war, though the last example was not withdrawn from a Territorial Army unit until February 1999.

The very last British Brens served in Army Cadet detachments, who used both .303in and 7.62mm versions. Most of these were withdrawn in the early 1990s, to be replaced by versions of the L86 LSW. The final two guns were not handed over to the Small Arms School Collection at Warminster, however, until February 2002, 64 years after the first gun was issued.

Twin Motley AA mount fitted in the back of a light truck at the Southern Command training school in Devon, 1942. The guns are fitted with 100-round AA drums, and the little-used bags to catch ejected cases are mounted underneath. (IWM H 23073)

Providing light anti-aircraft (AA) fire had been part of the original specification of the Bren gun.5 The Mk 1 tripod could be set up for AA work, and there were a number of specially designed AA mounts for vehicles, such as the Motley and Lakeman mounts.

A special 100-round drum (based on the drum magazine originally developed for the Vickers gas-operated aircraft gun) was issued for AA use, along with special clip-on AA sights. The magazine cover had to be replaced with a special bracket to mount the drum magazine, but this was a simple task. The drum was rather clumsy, and could not be used easily in the ground role, since it blocked the view through the gun’s normal sights. AA drums were only normally issued (in wooden boxes of four drums) to guns intended primarily for AA use, and very few infantry Bren gunners even saw one. Two slightly different patterns existed, the earlier of which had a separate winding handle, while this was built into the drum in the later pattern.

A second AA drum, the Vesely High Speed Drum, was produced in small numbers, but was not a success; it was almost twice the size of the normal drum, but only held 12 more rounds. This drum seems to be the cause of the occasional references to a ‘200-round High Speed AA drum’ encountered in the secondary literature, presumably on the basis that it was so much larger than the usual 100-round drum. So far as the author has been able to determine, no 200-round drum for the Bren was ever put into production.

However, the Bren was actually a relatively poor AA weapon, for two reasons. First, its rate of fire (around 500rds/min, depending on version and gas setting) was rather too low to engage crossing aircraft, with the gun only firing about eight bullets during the half a second or so when the aircraft was in the sights. By contrast, the German MG 42, which had been expressly designed with a much higher rate of fire (1,200rds/min) to allow AA fire, would fire 20 rounds in the same period. Various studies were made of ways to increase the Bren’s rate of fire, and achieved a rate of fire of over 700rds/min from the test guns. However, it was strongly felt that this was a little high for an infantry gun, which was after all its primary role, and no further action was taken. While mounting two guns together did help somewhat, it is worth remembering that at the point when the Bren was coming into service, the RAF was specifying eight of the high-speed version of the Browning .303in machine gun as the minimum armament for its new fighters, each firing at twice the rate of the Bren – a combined equivalent of around 9,000rds/min.

Scots Guards with a Bren on the Mk 1 tripod in its anti-aircraft configuration, 1938. The men still wear service dress and 1908 Pattern webbing, a reminder that the classic look of the World War II British soldier was only just coming in as the war began. The tripod could also be set up for the ground role, without the extended AA leg. (IWM Army Training 1938 1/29)

Top view of a Bren AA drum showing the webbing grip and arrow indicating the direction to wind up the drum’s internal spring. (Author)

Second, while rifle-calibre bullets might have been viable against the aircraft of the early 1930s when the Bren was designed, aircraft design moved on during the war. Cockpits and fuel tanks were commonly armoured, and aircraft guns increasingly moved to .50in calibre, or even 20mm. This meant that the .303in rounds from the Bren were significantly less likely to bring down an aircraft than the rounds from the .50in M2 machine gun the US Army used in the AA role, though in fairness this was a much heavier gun that could not have replaced the Bren.

Given this, it is perhaps fortunate that Allied air superiority after D-Day meant that the Bren saw little use in the AA role. Indeed, Allied troops were explicitly ordered NOT to fire at any aircraft for much of the campaign, after the RAF and USAAF complained of frequently taking ground fire from Allied units despite the black-and-white ‘invasion stripes’ painted on their aircraft to avoid such incidents.

Despite this, the Bren continued in the AA role after World War II; the six-wheeled Saracen APC that served through the 1960s had an AA Bren on a ring mount over the infantry compartment as well as its turreted Browning. Given that the targets by that point would have been Soviet jets, one may feel that this was slightly optimistic. No drum magazines were produced or adapted for the 7.62mm NATO versions of the Bren.

The original specification for the Bren paid very little attention to its possible use as a tank gun. Partly, this is because when the specification was developed, the British Army was not mechanized, and still relied on mounted units for traditional cavalry roles such as reconnaissance. Even those who believed the tank was the weapon of the future, rather than a one-off response to the unique conditions of the Western Front, were not sure of the role or design of future tanks.

Previous British tanks had used the various British machine guns in service (Vickers, Lewis and Hotchkiss) without significant modification, so it was not really appreciated that tank use really had any particular requirements, and indeed, the ZGB was described as ‘A most promising weapon for use in the Royal Tank Corps’ (SAC 1420) in a 1935 minute from the RTC gunnery school. Unfortunately, the machine guns in previous British tanks had been installed in dedicated mounts with an individual gunner for each machine gun. Things were very different in the tanks of World War II, where the machine gun was often mounted in a much tighter space as a co-axial weapon next to the main armament.

A Bren in the cramped turret of a Humber Light Reconnaissance Car. The turret on this vehicle was open-topped to allow the Bren to be used against aircraft as well as ground targets, but gives an idea of how awkward it would have been to use it as a vehicle co-axial gun on tanks or similar vehicles. (IWM H 25271)

A Universal Carrier of The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, 1940. This vehicle has its Bren gun on the AA pedestal mount and its Boys .55in anti-tank rifle in the firing port in the front plate. It was also common to mount the Bren in the latter location, however, particularly later in the war when the Boys was no longer effective against improved enemy armour. (IWM H 4954)

The Bren quickly proved unsuitable for this role. Its top-mounted magazine limited the angle of depression possible in a fixed mounting, its magazine capacity was too small and too awkward to change in a confined space, and it relied on a quick-change barrel for sustained fire. As a result, the British Army adopted a second Czech design, the Zb 53, as the Besa tank gun. It was a belt-fed weapon with a heavier barrel. It was a solid and dependable weapon that served as a co-axial gun on British tanks through to the A34 Comet, but obviously, having multiple designs in service complicated spare-part supply and training.

To make things worse, the Lend-Lease tanks supplied by the United States (such as the M4 Sherman) that made up a significant part of the British tank fleet used yet another design (the .30in M1919 Browning) as their co-axial weapon. It was not until the adoption of the L7A1 GPMG that the British Army finally got one gun which could fulfil both the infantry and tank roles adequately, and even then, Browning guns soldiered on in service aboard older types such as the Ferret and Saracen into the 1970s.

The Bren was a perfectly viable gun on open-topped vehicles, such as the Daimler Dingo scout car and Universal Carrier. Indeed, it became so closely associated with the latter vehicle that it was almost universally known as the ‘Bren Gun Carrier’.

While the service history above has concentrated on the British and Commonwealth forces that were the main users of the weapon, other forces also used the Bren.

Jewish irregular groups such as Haganah used Brens stolen from British forces in attacks against British troops administering the League of Nations mandate in Palestine, and against Palestinian Arabs they believed were attacking Jewish communities, attempting to drive them out so that a Jewish homeland could be established in Israel. When the United Nations resolved to set up such a state in 1947, Israel’s Arab neighbours objected to the resulting partition of Palestine, and invaded the new state within hours of its independence in 1948. Both Arab and Israeli forces in the 1948 war used Brens as their primary LMG, and some remained in service with the Israeli Defence Forces into the 1956 war, after which they were generally replaced by the Belgian FN MAG.

The Irish Army adopted largely British-manufactured weapons, and Irish troops were equipped with Bren guns as support weapons when they deployed as UN peacekeeping troops to the recently independent Republic of the Congo in 1960. Ethnic and political tensions in the former Belgian colony had led to civil unrest and the secession of the province of Katanga from what the UN recognized as the legitimate government.

A company of 155 Irish troops was besieged in the town of Jadotville by Katangese forces, under repeated attacks including air attacks by an aircraft piloted by a Belgian mercenary, and surrendered after six days when their ammunition ran out. Although these troops were later exchanged, ambushes against the Irish peacekeeping forces continued until the Katangese forces were defeated by the Congolese government in 1962. The most costly of these ambushes, at Niemba, saw an 11-man Irish patrol almost completely wiped out, despite killing almost three times their number of enemies with a Bren and a submachine gun. Irish forces had left the country before the 1964 rebellion, which led to the well-known parachute drop by Belgian para-commandos to rescue and evacuate western hostages from the region. The Bren was later replaced in Irish service by the FN MAG.

On the other side – Zb 26s in foreign service

As well as forming the basis for the British Bren, the Czech Zb 26 was itself purchased by a number of other countries, including Bolivia (who used it in the Gran Chaco war of the 1930s), Ethiopia (whose forces used it against the invading Italians) and Turkey.

Waffen-SS troops with a Zb 30 LMG; this is evidently a training photograph, as the usual muzzle cone has been replaced by a cylindrical blank-firing attachment. (IWM MH 1912)

The Zb 26 and its successor, the Zb 30, were also used by the forces of several of the Axis Powers. Romania produced the design under licence, and it was used by Romanian forces fighting alongside the Germans on the Eastern Front. Meanwhile, thousands of Czech guns, captured when the Nazis annexed that country and already chambered for the same 7.92mm Mauser cartridge used by the Wehrmacht, were taken into German service as the MG 26(t) and MG 30(t), respectively. Most went to the Waffen-SS, who had a lower priority for supply than the Heer (German Army) at this early stage of the war. The Germans continued to run the Brno factory throughout the war, producing Zb 30 guns both for themselves and for allies such as Franco’s Spain, who received 20,000 guns.

The Nationalist Chinese bought a considerable number of Zb 26 guns, and ultimately set up several factories to produce the weapon. These were initially used both during the civil war and against the invading Japanese. After the communist takeover of China, they were used against United Nations forces by Chinese troops during the Korean War. The Chinese also supplied examples to the Vietnamese communist forces, which were used against first French and then American forces.

The Germans also put actual Brens captured in action into use as the 7.7mm Leichte MG 138(e). By contrast, the Allies explicitly prohibited their troops from using captured machine guns, since the MG 34 and particularly the MG 42 made a very distinctive ‘ripping cloth’ noise due to their high rate of fire; any other Allied troops hearing it tended to pour fire at the source of the sound without waiting to see who was firing the gun.

The last time that British troops faced Zb-series weapons was in Afghanistan, where a Turkish-made Zb 30 was captured by British forces in 2009, 70-odd years after it was produced. The gun is now held at the Small Arms School Museum in Warminster, Wiltshire.

Both the Indian and Pakistani armies were initially equipped with British equipment when the countries were partitioned on independence in 1947. Both thus used the Bren as their standard LMG in the 1947 war that broke out between the two when there was not a clear line between the Hindu and Muslim populations that the new border could follow, and over Kashmir, where the local ruler was allowed to choose which of the two states it joined. Both continued to use the Bren in the 1965 war, and in the case of Indian forces, for the 1971 war. A version of the Bren remained in production at the Ishapore arsenal as the MG1B until recently, and only began to be withdrawn from Indian service in 2012.

Nigeria gained independence from Britain in 1960, but was a somewhat artificial entity, with tensions between the Muslim, traditionalist north and more westernized and Christian south. This led to ethnic violence and the breaking away of the south-eastern part of the country to form the state of Biafra in 1967. Nigerian forces were largely equipped with British small arms, including the Bren, during the war, which lasted until 1970, and some 7.62mm NATO Brens remained in service for a considerable time afterwards.

In 1983, the pro-communist government of Grenada was deposed in a coup by hard-line elements of its own military, who executed the prime minister and a number of other ministers and government officials as well as firing on demonstrators. Concerned for the safety of over 1,000 US citizens on the island, the US government intervened, landing troops to take over the island and secure the medical school campus where most of the US citizens were located.

While the invasion itself was carried out by US forces, the United States was keen to avoid accusations of unilateralism by involving other Caribbean countries in the operation. Several countries therefore provided troops or police to assist with security after the invasion. This included contingents from Barbados and Jamaica, both of whom were photographed with the L4A2 Brens they had brought as support weapons.

__________________

3 The ammunition pouches of ’58 Pattern Webbing were a little deep for standard 20-round SLR magazines. To enable them to be reached more easily, it was common practice for troops to put extra field dressings into the bottom of the pouches, to raise the magazines for easier access.

4 A disintegrating link belt is made up of stamped sheet metal links, each holding one round and attaching to the link on either side of it. The mechanism of the gun separates and ejects the links as ammunition feeds into the gun. While more complex than the webbing belts used on older guns such as the Vickers, the metal disintegrating link belts do not absorb water and freeze, and the gunner is not hampered by lengths of expended belt hanging out of his weapon.

5 Technically, the British Army considered ‘light’ anti-aircraft weapons to be the 20mm Oerlikon and Polsten cannon, and the 40mm Bofors gun, as distinct from the ‘heavy’ anti-aircraft guns of 3.7in or larger. However, in practice the Bren was commonly termed ‘light AA’ even if it didn’t meet the technical definition.