Conflict, unrest and protest

Conflict, unrest and protest

The vanquishing of the Armada

Sir Francis Drake’s report on the Battle of Gravelines

SUMMER 1588

The Spanish Armada – fought between 29 July and 12 August (New Style; Old style by English reckoning 19 July–2 August) – is one of the most famous events in English history. Not only did it ensure the survival of Elizabethan Protestant England but the victory was a milestone in the history of the Royal Navy, heralding its inexorable rise to the formidable instrument of British global power it would later become.

Had the Armada invasion of 1588 succeeded, it is debatable whether England would have suffered the humiliation of total annexation to the Spanish Empire. Nevertheless, Elizabeth would have most likely been deposed and England forcefully returned to the fold of the Catholic Church. At the very least the price of peace with Spain for Protestant England would have included agreement to end all military and financial aid to Dutch rebels in the Spanish Netherlands and attacks on Spanish ships and settlements by English privateers.

Though King Philip II of Spain was an intelligent and meticulous planner, some of his own subjects believed the king’s ‘enterprise of England’ was a flawed endeavour from the outset. The delays and disruption to preparations caused by the lack of a centralised system of naval administration meant that any hopes of secrecy were quickly extinguished. Moreover, the Marquis of Santa Cruz, the Armada’s commander until his death in February 1588, shared private concerns with fellow officer, Martin de Bertendona, about the lack of a deep-water port in Spanish hands in Flanders. This would have enabled Spanish forces being marshalled by the Duke of Parma to embark safely under escort from large Spanish warships. Parma in correspondence with Philip had even identified the port of Flushing as a secure and suitable port for embarkation if it could be successfully captured from Dutch rebels.

Such wise foresight was considered negligible or too inconvenient by Philip but would prove to be the critical flaw in the Armada plan. Once the Spanish fleet, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, had successfully sailed through the English Channel, larger Spanish vessels could not safely sail close to shore in the treacherous shallow waters around Dunkirk and Calais where Parma’s army had assembled. Without their protection, Parma’s army was highly vulnerable to attack by Dutch shallow draft vessels known as ‘flyboats’ patrolling close to Dunkirk.

Sir Francis Drake.

Nevertheless the Armada, with a total complement of over 19,000 soldiers and 8,500 sailors, posed a grave threat to Elizabethan England in its own right. The battle that took place off Gravelines on the Flemish coast on 8 August (New style; Old style 29 July) between English and Spanish fleets was the climax in naval operations during the armada episode and would prove crucially decisive. The English navy under the command of Admiral Lord Howard of Effingham had not succeeded in breaking the Armada’s rigid defensive formation nor inflicted much damage to Spanish ships as the fleet made its way down the English Channel. New tactics it seemed would be required. On the night of 7 August (New Style; Old Style 28 July) several English fire ships were unleashed on the Spanish fleet laying at anchor near Calais and despite efforts to hold formation, the Armada scattered. The following morning English vessels with their superior firepower and manoeuvrability attacked, now daring to fire their broadsides at closer range to devastating effect. Two ships were sunk and two more driven onto the shoals whilst many others sustained serious damage. Sir Francis Drake in his letter to Sir Francis Walsingham celebrated that ‘God hath geven us so good a day in forcing the enemy so far to leeward as I hope in god the prince of parma: and the duke of Sodonya shall not shake handes this fewe dayes.’

The Spanish fleet was now in mortal danger of being driven by winds onto the perilous sandbanks of Zeeland, though fortunately, the winds changed at the last minute allowing the fleet to escape northward. In requesting further munitions and victuals, Drake’s letter showed that he believed their fight was far from over, a view shared by his fellow commanders. Unbeknown to them, Spanish morale had been fatally weakened and with dwindling supplies, prevailing northerly winds and the determined pursuit of the English fleet, any resolve to offer further defiance shattered. The Armada would thus limp home via the turbulent seas around Scotland and western Ireland. Though flawed Spanish planning and the turbulent weather played their part, ultimate acclaim should be reserved for Drake and fellow commanders and sailors of the Elizabethan navy in the victory against the might of the Spanish Empire.

Right ho[nourable] this bearer cam [came] a board the ship I was in in a wonderful good tyme and brought with hym as good knowledge as we culd wyshe, his carffulnes therin is worthy recompence for that god hath geven us so good a day in forcying the enemy so far to leeward as I hope in god the prince of parma: and the duke of Sodonya shall not shake handes this Fewe dayes, And when so ever they shall meet. I beleve nether of them will greatly reioyce of this dayes Servis the town of Callys [Calais] hath seene sum p[ar]te thereof whose major yo[ur] ma[jes]tie is beholding unto: businis comandes me to end, god bless her ma[jes]tie our gracyous Sovraygne and geve us all grace and leve in his feare, I asure yo[ur] ho[nour] this dayes S[er]vis hath mych [much] apald the enemy and no doubt but incoraged ou[r] army from a board her ma[jes]ties good ship the revenge this 29th July 1588 [Old Style; New Style, 8 August 1588]

Yo[u]r ho[nour’s] most redy to be co[m]manded

Fra[ncis] Drake

….ther must be great care taken to send us whether so ever the enemy goeth monycyon [munition] and vittual [victual]. Yo[u]rs Fra[ncis] Drake.

Home front anguish during the English Civil War

An unknown woman speaks out about suffering

17 OCTOBER 1645

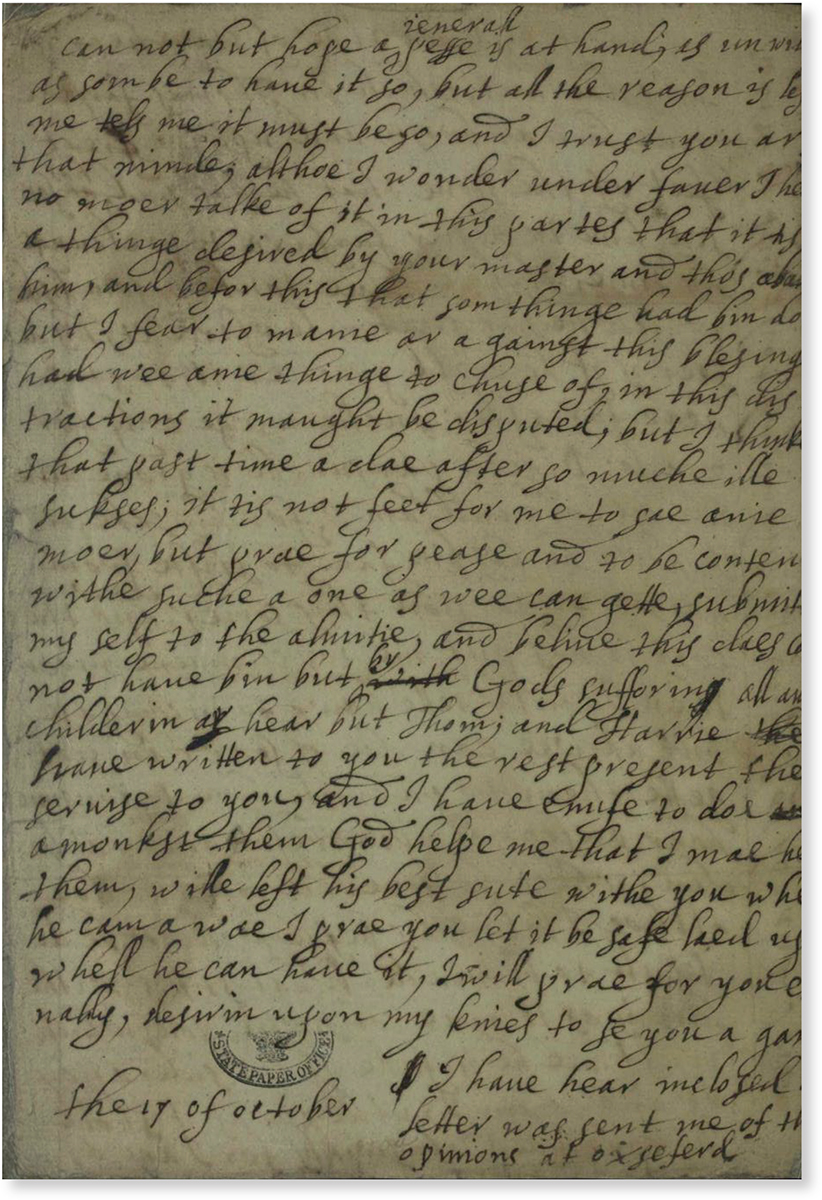

The English Civil War lasted nearly a decade and had a devastating impact on Britain on both a personal and political level: rifts were created in families that took generations to heal, and seven per cent of the population died as a direct result of the fighting or the famine or disease that arose in the wake of the war. For women on both sides of the conflict the effect on their lives was immense. Often they were the ones left trying to hold families together or to maintain households deprived of financial support. They lost husbands, sons or homes or were driven into exile. This fragment of a letter from an unknown woman on the Parliamentary side provides an insight into the privations suffered and the upset felt in both camps.

The writer herself describes it as a distressed letter and it conveys an immediate uncensored anguish: her feelings tumble out in a stream of consciousness unfettered by punctuation. She tells of the financial burden experienced by families struggling to support husbands and sons shifted from garrison to garrison and of the suffering and uncertainty felt by families who often did not know where their soldiers were or even if they were still alive. She appeals for peace but consigns herself to her God. She is devout, patriotic and ready to die for her country but also resents the burdens placed upon herself and her family.

This letter has lain among the State Papers for nearly 400 years. We have no way of knowing whether the writer’s plea was heard or what happened to her. Her emotions, however, cut through the centuries and convey a sense of immediacy to the reader. Like all the best letters, it provides an insight into an individual’s state of mind and can add a personal dimension to a national conflict.

Another woman from the period, Margaret Eure, wrote ‘in my poor judgement these times can bring no good end to them, that all women can do is pray for better for sure it is an ill time’. This letter is one such prayer.

Oliver Cromwell.

A publication distributed to those fighting on the Parliamentary side.

sir Thomas farfaxe gaue him at bristo and upon a great feet of the stone that he has had has forsed him to desier farfaxse to prelaunge his time, whell he haue touken som fisike which he has great nide of; next, his desier is if he could precuer it, to stae hear, for after suche usege only for my Lo: Digebes pleasur, he is grone uerie werie of, and so am I, for his sake, to se hawe he has bin fane to shifte from garison to garison this somer, and the cost it has put me to; so muche moer then I could telle hawe to incompase but all wee can doe I fear can not gette them to parmite him to continue hear exsept he apear befor them at londen, which he is uerrie lothe to doe althoe I beliue his pesse will not be difficult to be made; What stikes withe him is as it mae conserne you, which trust me he is fulle of consideration of and so am I, uther was it shold be concluded of qwikly for I am as wearie of thos that haue bin his enimis as he, and I beliue so is the publike which is worst of all; I as som be to haue it so, but all the reason is left me tels me it must be so, and I trust you ar of that minde; althoe I wonder under fauer I hear no moer talke of it in this partes that it tis a thinge desired by your master and thos about him, and befor this that som thinge had bin don but I fear to manie ar against this blesinge had wee anie thinge to chuse of, in this distractions it maught be disputed; but I thinke that past time a dae after so muche ille sukses; it tis not feet for me to sae anie moer, but prae for pease and to be content with suche a one as wee can gette, submiten my self to the almitie, and beliue this daes cold not haue bin but by Gods suffering all awe childerin ar hear but Thom; and Harrie haue written to you the rest present ther seruise to you, and I haue enufe to doe amonkst them God helpe me that I mae help them, wille left his best sute with you when he cam awae I prae you let it be safe laed up whell he can haue it, I will prae for you et[er]nally, desirin upon my knies to se you a gan

I haue hear inclosed a Letter was sent me of the opinions at oxseferd

the 17 of october

Endorsed: 17 Octob 1645 I beleeue this letter came from the Ladie of Barkshire

Political plea for a privateer

Despatch from General George Washington to Sir Guy Carleton

24 DECEMBER 1782

This document sent from the American Continental Army’s headquarters at Newburgh (on the Hudson River) to Guy Carleton, commander-in-chief of British forces in North America at New York, relates to: an inquisition into the murder of Captain Huddy; the treatment of German prisoners; and the granting of a passport for a vessel to proceed from Philadelphia with provisions for American naval prisoners. The American Revolutionary War was essentially not one war but two.

First, there was a civil war with the American Colonies, beginning in 1775 and ending at Yorktown (Virginia) in October 1781; and then there was a second war, which started in 1778 when France (and later Spain and the Dutch Republic) entered the conflict in support of the Patriot cause. This conflict would last until September 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was ratified. During the second war, Joshua ‘Jack’ Huddy, the commander of a New Jersey Patriot militia unit, was summarily hanged in April 1782 by pro-British Associated Loyalist irregulars – an event that became a motive force behind one of the first international incidents of the fledgling USA.

As an officer, Huddy had been removed from British custody at New York by a band of regional Loyalists, ostensibly for the purpose of making a prisoner exchange. However, no such exchange was forthcoming. More than 400 people eventually gathered to protest at his execution, and a petition was sent to General Washington demanding retribution. Both Washington and Carleton condemned the hanging and prompted the British to forbid the removal of any further prisoners.

George Washington.

As early as February 1776, Reading (Pennsylvania) was already receiving German prisoners in the service of the British Crown. Prior to 1781 the majority of these Hessian or Brunswick mercenaries were officers, and although prisoners of war (POWs) were not allowed to leave their barracks without permission, grants of parole allowed many officers to go to Philadelphia or New York. However, many private soldiers escaped and made their way back to the British lines, as the mostly German-American citizens of Reading were harsher in their treatment of their own countrymen than they were of English, Scottish or Canadian prisoners.

American prisoners were not legally recognised by Parliament as ‘prisoners of war’ until March 1782 (six months after the British surrender at Yorktown by Cornwallis), a status that allowed them to be detained, released or exchanged. This method of dealing with ‘rebel’ prisoners provided Britain with a free hand to deal with her captives by any method she saw fit. Moreover, the appalling conditions aboard British prison ships (such as the Whitby and the Jersey) were well known to the Continental Congress at Philadelphia, and had led many American sailors to enlist in the Royal Navy out of desperation.

Although the British commissary of naval prisoners suggested that American marine prisoners coud be exchanged for British soldiers, Washington refused to negotiate as it would have provided the British with considerable reinforcements (of troops) and would have caused a depletion of prisoners in American hands available for exchange. What’s more, this would also have provided no benefits to the Continental war effort as most of the American naval captives in New York were from privateering vessels.

Head Quarters 24th Decr 1782

Sir

I have been favored with your Excellency’s three several letters of the 11th and 12th instant covering the report of the Judge Advocate of your Army, respecting a further inquisition which had been proposed to be made into the murder of Capt. Huddy; a representation of Lieut. Reinking relative to the treatment of the German prisoners at Reading, and a Passport for a vessel to proceed from Philadelphia to New York, with necessaries for our Naval Prisoners.

I should have done myself the honor of acknowledging the receipt of these Despatches some days sooner, had I been myself sufficiently possessed of the facts, to have given so particular or explicit an answer to Mr. Reinking’s Representation as I wished, without having recourse to the Gentleman who is immediately concerned in the safekeeping the Prisoners of War – having obtained a reply from the Secretary at War to my letter on this subject, I now take the liberty of inclosing a Copy of it to your Excellency –

I am much obliged by your mentioning the state of the American Marine Prisoners As the management of that business was properly in the department of the Agent of Marine, I have given an extract of your Letter to Mr Morris, and flatter myself the necessary relief will be provided for them without delay.

Some time previous to the receipt of your Letter, in which you mention the situation of Captain Schaack, permission had been given for that Gentleman to go into New York on Parole, and I am unacquainted with the reasons which have prevented his arrival at that place.

I have the honor to be

Sir

Your Excellency

Most obedient and

very humble Servant

George Washington

A complex command

Horatio Nelson to William Marsden, Secretary of the Admiralty

7 AUGUST 1804

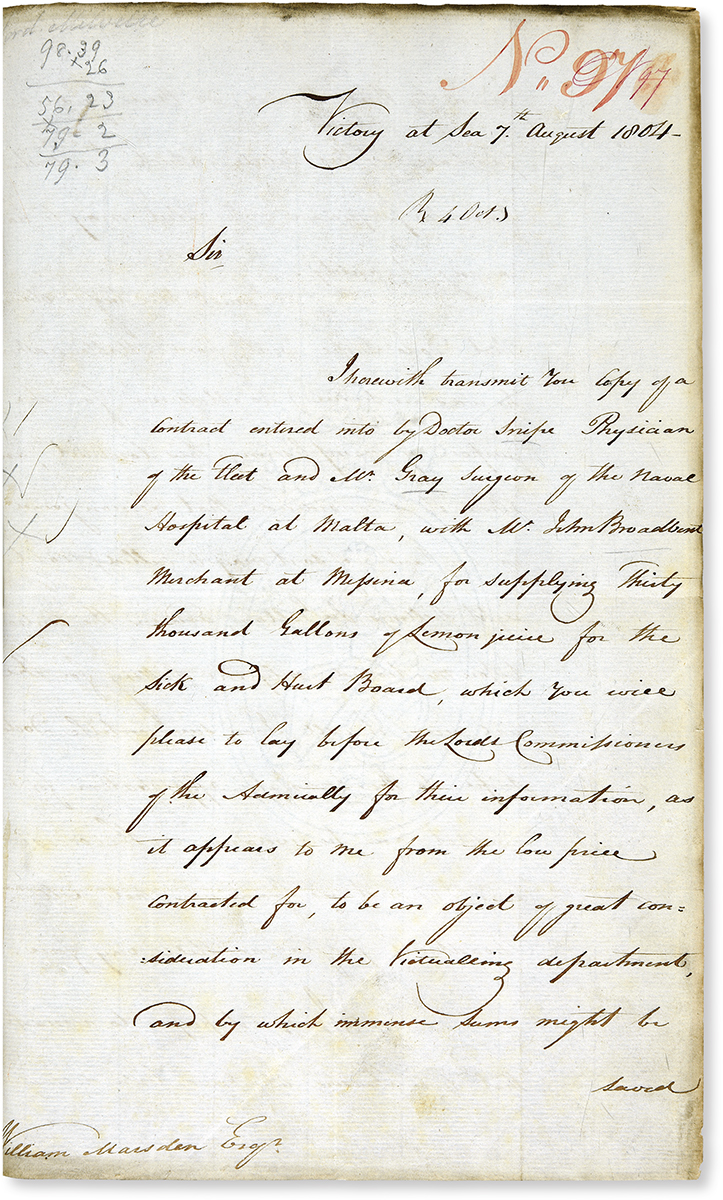

In May 1803, ahead of renewed hostilities between Britain and France, Horatio Nelson was appointed commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean. Aged forty-four, he was the youngest ever given this command in Royal Navy history. A proven exceptional battle-fleet commander, having had successes at the battles of the Nile (1798) and Copenhagen (1801), this appointment was to be his sternest test in twenty-three years of naval service.

Nelson was tasked to blockade Napoleon’s French Mediterranean fleet at Toulon and, if it escaped, to destroy it, thus safeguarding Britain from Napoleon’s invasion threat. Additionally he had to: defend the Strait of Gibraltar; protect British seaborne trade; maintain diplomatic relationships; gather intelligence; cultivate relations with potential European allies; and keep in check French and Dutch enemies while also monitoring potential future enemies such as Spain.

Balancing the competing demands of this complex command, Nelson also had to ensure the provisioning and fighting efficiency of his ships and the health of men serving in this fleet. He was to achieve this initially with only nine ships, in a vast theatre extending ‘3,000 miles from Cape St Vincent, Portugal to the Levant’ without modern communication systems and virtually independent from British government control – Toulon being more than 2,000 miles from London, and 600 and 700 miles respectively from the only British naval Mediterranean bases, Gibraltar and Malta. Nelson met these expectations by serving on his flagship, HMS Victory, at sea for nearly two years without setting foot on land, and by bringing to the fore his administrative skills and attention to detail.

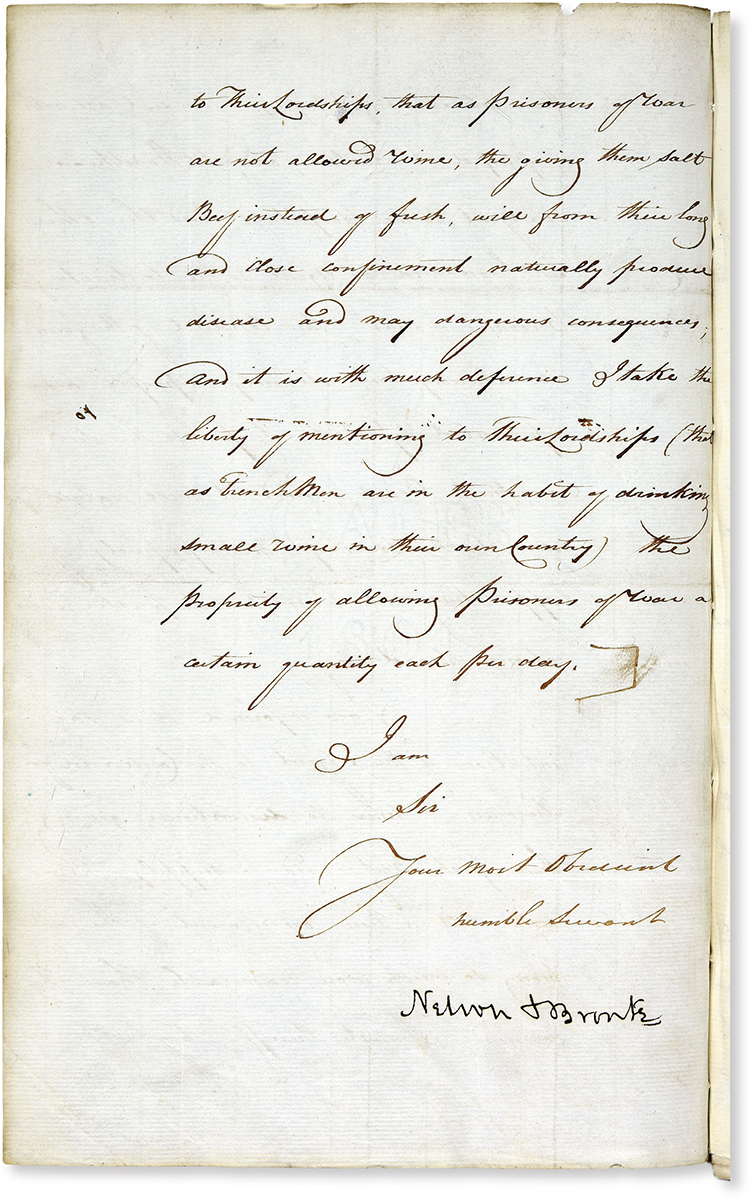

This is evidenced in a letter dated 7 August 1804 by Nelson to William Marsden, Secretary of the Admiralty. Typically direct, it reveals different facets of Nelson’s workload and character, highlighting his authority in handling significant operational issues. The importance of the contract agreed by Doctor Snipe and Surgeon Gray for 30,000 gallons of lemon juice – an effective preventative against scurvy, and beneficial for his men’s health – shows Nelson’s practical knowledge of its cost in England and its inferior quality to that produced in Messina, Sicily, but also that buying it from Messina would result in savings to the public purse as it was closer to where his ships were stationed. It also reveals Nelson’s trust in Snipe and Gray to negotiate such a contract; allowing colleagues to act on their initiative strengthened bonds with peers and was a classic Nelson leadership trait.

Horatio Nelson.

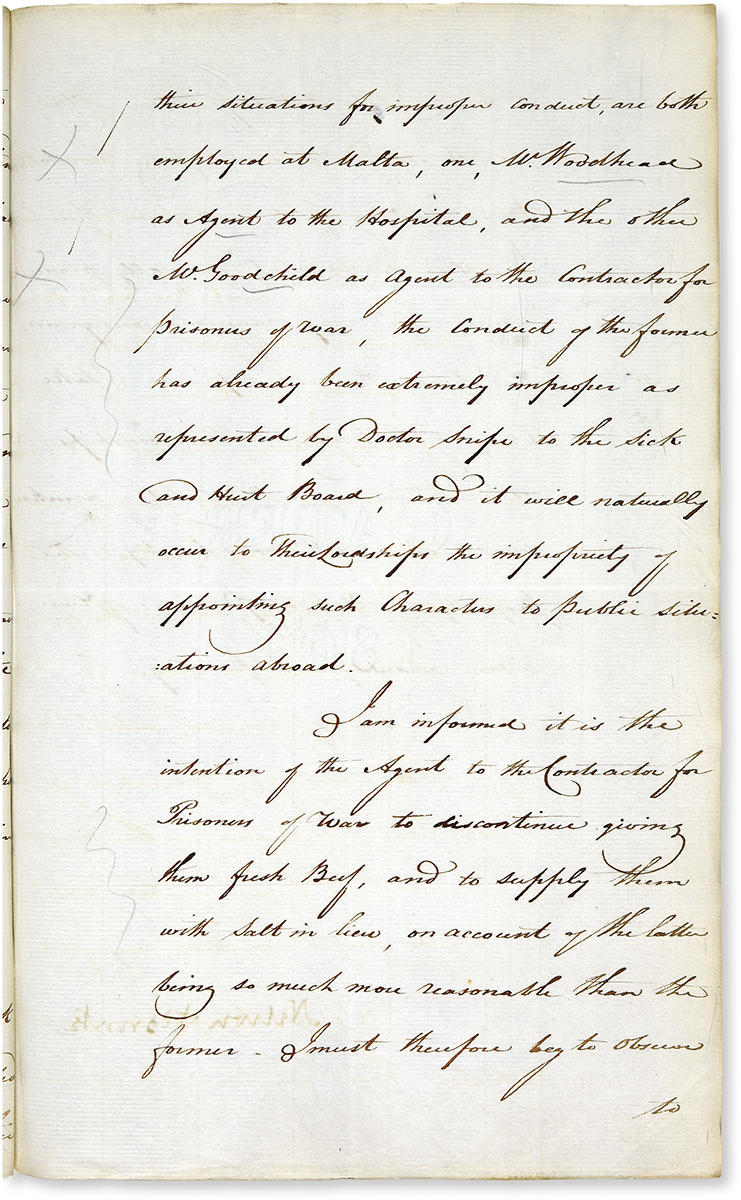

Nelson’s sense of honour and devotion to public duty entailed a constant keeping of his finger on the pulse. This is highlighted by his comments concerning the ‘impropriety’ of two pursers dismissed from their previous employment due to ‘improper conduct’ to positions of relative importance in ‘public situations abroad’.

Nelson’s expressed views about prisoners of war, considering his perceived ruthlessness in battle, are revelatory. His hatred of the French inculcated by his mother when he was a boy is well known: indeed, in 1793 Nelson famously told a midshipman on HMS Agamemnon ‘you must hate a Frenchman as much as you hate the devil.’ Perhaps this sentiment is not surprising given that for much of his lifetime France had been at war with Britain and that Napoleon represented everything diametrically opposite to his political and monarchical beliefs.

Despite this, however, this letter reveals Nelson’s humane side – often lauded by his fellow officers and men – which was extended to enemies, including the hated French. For instance, he informed the governor of Barcelona on 16 November 1804: ‘it is the duty of individuals to soften the horrors of war as much as possible’ and this humanitarianism underpins his assertions:

‘as prisoners of war are not allowed wine, the giving them salt beef instead of fresh, will from their long and close confinement naturally produce disease and many dangerous consequences, and it is with much deference I take the liberty of mentioning to their Lordships (that as French men are in the habit of drinking small wine in their own country) the propriety of allowing prisoners of war a certain quantity each per day’.

The overriding testimony to Nelson’s efficacy as commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean was the stunning victory by his fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805, which thwarted Napoleon’s invasion plans of Britain and established Britain’s undisputed mastery at sea for more than a century.

Victory at Sea 7th August 1804

Sir,

I herewith transmit you Copy of a contract entered into by Doctor Snipe Physician of the Fleet and Mr Gray Surgeon of the Naval Hospital at Malta, with Mr John Broadbent Merchant at Messina, for supplying Thirty thousand Gallons of Lemon juice for the Sick and Hurt Board, which you will please to lay before the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty for their information, as it appears to me from the low price contracted for, to be an object of great consideration in the Victualling department, and by which immense Sums might be saved by that Board in their future purchase of this Article, which I understand from the Physician of the Fleet may be had in any Quantity.

I must here beg to observe that Doctor Snipe went from Malta (where he was on Service) to Messina for the purpose of accomplishing this Contrait [contract], and when it is considered that Lemon juice in England (if so it may be called) cost eight shillings per Gallon, and in the contract before mentioned only one Shilling for the real juice, it will I am sure entitle Doctor Snipe to their Lordships approbation for his conduct and perseverance on the occasion, and I understand from him that Mr Broadbent’s profits are still very fair.

I judge it proper to remark that two Pursers who have been dismissed their situations for improper conduct, are both employed at Malta, one, Mr Woodhead as Agent to the Hospital, and the other Mr Goodchild as Agent to the Contractor for Prisoners of War, the conduct of the former has already been extremely improper as represented by Doctor Snipe to the Sick and Hurt Board, and it will naturally occur to their Lordships the impropriety of appointing such Characters to Public Situations abroad.

I am informed it is the intention of the Agent to the Contractor for Prisoners of War to discontinue giving them fresh Beef, and to supply them with Salt in lieu, an account of the latter being so much more reasonable than the former, I must therefore beg to observe to Their Lordships, that as Prisoners of War are not allowed Wine, the giving them Salt Beef instead of fresh, will from their long and close confinement naturally produce disease and many dangerous consequences, and it is with much deference I take the liberty of mentioning to their Lordships (that as French Men are in the habit of drinking small wine in their own Country) the propriety of allowing Prisoners of War a certain quantity each per day.

I am

Sir

Your Most Obedient

humble Servant

Nelson & Bronte

‘The Lane down to your farm is dark...’

Words of warning during the Swing Riots

1830

Revolution is often seen as something that starts in cities and in the nineteenth century Britain’s rulers warily watched the urban working classes, fearing that these men and women crammed higgledy-piggledy into filthy towns would explode like a tinder box, demanding greater rights.

However, in the winter of 1830–1831, the greatest threat to the ruling classes in fact came from desperate, disenfranchised agricultural workers in rural southern England, who unleashed a wave of fire and fury popularly known as the Swing Riots.

Swing was a product of economic distress. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 had led to a contraction in Britain’s internal and European markets, as well as an influx of workers demobilised from the armed forces.

The fifteen years that followed were ones of low wages, bad harvests, discontent and disorder. Groups and demonstrations calling for parliamentary reform flourished and were often violently supressed, as was the case at the 1819 Peterloo Massacre in Manchester. This period also saw genuine rising and attempts at violent revolution, such as the abortive Pentrich Rising in 1817.

In 1830, agricultural labourers in the south of England were in dire straits. Failed harvests and the introduction of labour-saving threshing machines led to less work, lower wages and higher prices. Many were left without the means of subsistence.

In November 1830 in Kent, where this letter to Thomas Hodges MP was sent, these downtrodden men began what became a spontaneous wave of disorder and insurrection that spread across southern England and into the Midlands.

Under the banner of the mythical Captain Swing, the rioters destroyed threshing machines, burned down barns and other buildings, and threatened violence on landowners, whether by a mob surrounding a house or the sending of a threatening letter such as this one.

One commentator observed that it seemed the men sought ‘to strike back terror upon the terrorists’ but the rioters had clear demands, too: better wages, the destruction of the threshing machinery that took their work, and a reduction of tithes paid to the church, which depleted their already meagre wages.

Letters like this were typical of the tactics, but they were empty threats. Despite the promise that ‘I kills you’ and claims that special constables would be shot, few Swing rioters were armed at all and the only person to die during the disturbances was himself a rioter.

This letter is interesting in that the writer claims to be French but is probably not: the poor spelling and grammar is almost certainly due to illiteracy. It is likely that the writer is merely pretending to be French in an attempt to strike further terror into the letter’s recipient – France had had its own revolution in July 1830 and there were fears that French agents were directing the riots.

The Swing Riots were not successful. Promises made to pay higher wages while they were happening were quickly rescinded afterwards. Nineteen rioters were hanged, more than 600 imprisoned and almost 500 transported to Australia. However, the Riots did hasten the collapse of the Duke of Wellington’s government, allowing Earl Grey’s Whig administration to introduce the 1832 Great Reform Act, beginning the long road to universal suffrage in Britain.

A mob in Kent burning a hayrick during the Swing Riots.

Charity Street Hotel de France

My spelling is bad but de [sic] French are not so English.

I write you these few lines meerley to give you warning. I’m one of 3 thousand who mean to pull to de ground your house which is called Hemstedd next week and dip your head in de horse fuel. Maye you think that soldiers will find us, no no I kills you. Monsieur with his sussix friend will rout 10 thousand red herrings. You may harke into your hearts dasire with Colne Monsieur will not deceive de English be upon it, if we do not come de moon does not shire nor de stars look bright to night. My man will soon shoot 50 of your special constables-----------

The Lane down to your farm is dark-

we will light it up.

All your tenants farms are Dark.

Ditto

Sulphuring W[ith] heat – J S Now only one

[one line illegible]

The little things count

The War Office to Lord Kitchener on provision for Indian troops

14 DECEMBER 1915

Approximately 1.3 million Indian soldiers served in the First World War, and more than 74,000 of these lost their lives. In the first few months of the war in particular, the Indian Army played a vital role: at a time when Britain was still recruiting and training volunteers, soldiers from across the Empire came to fight on the Western Front and support the British cause. The Indian Army provided the largest number of troops, and by the end of 1914 they made up almost one-third of the British Expeditionary Force.

Indian troops first arrived in France from the end of September 1914. Here they were greeted with flowers and gifts, a signal that the French were very grateful for their contribution.

A further sense of gratitude was extended when the Indian Comforts Fund was set an express target to provide comforts to Indians serving on the Western Front who were unable to go home. In correspondence from Sir Walter Lawrence (who had been appointed Commissioner for the Welfare of Indian Troops) to Lord Kitchener (Secretary of State for War), we are given an insight into how this affected the spirits of these Indian soldiers.

Lawrence writes to Kitchener on 14 December 1915 saying that the little things count and that the Indians are impressed by the care taken about their religious observances – which include a temporary mosque and arrangements for reading holy scriptures.

Similar arrangements were being made back in England, with the Royal Pavilion in Brighton being converted into a hospital for wounded soldiers. From 1914 to 1916, this was used for Indian soldiers who had been wounded on the Western Front; the architectural style of the building and interior was deemed appropriate for making Indian soldiers feel at home while they were convalescing. The first patients arrived early in December 1914, and over the next year around 2,300 Indian patients were treated there.

It wasn’t just the medical needs of the patients that were catered for though: again, a lot of effort was taken to cater for religious and cultural needs. Muslims and Hindus were provided with separate water supplies; nine kitchens were set up to cater for the different religious and caste traditions relating to food; and different areas for prayer were established around the site. Arrangements were also made for those who died in the hospital – with a site for open-air cremations for Sikhs and Hindus at Patcham, and a special cemetery in Woking for Muslims.

The letter suggests that all of this had a positive effect on the morale of the troops of the Indian Army, and that the men themselves were very pleased with how they were being treated.

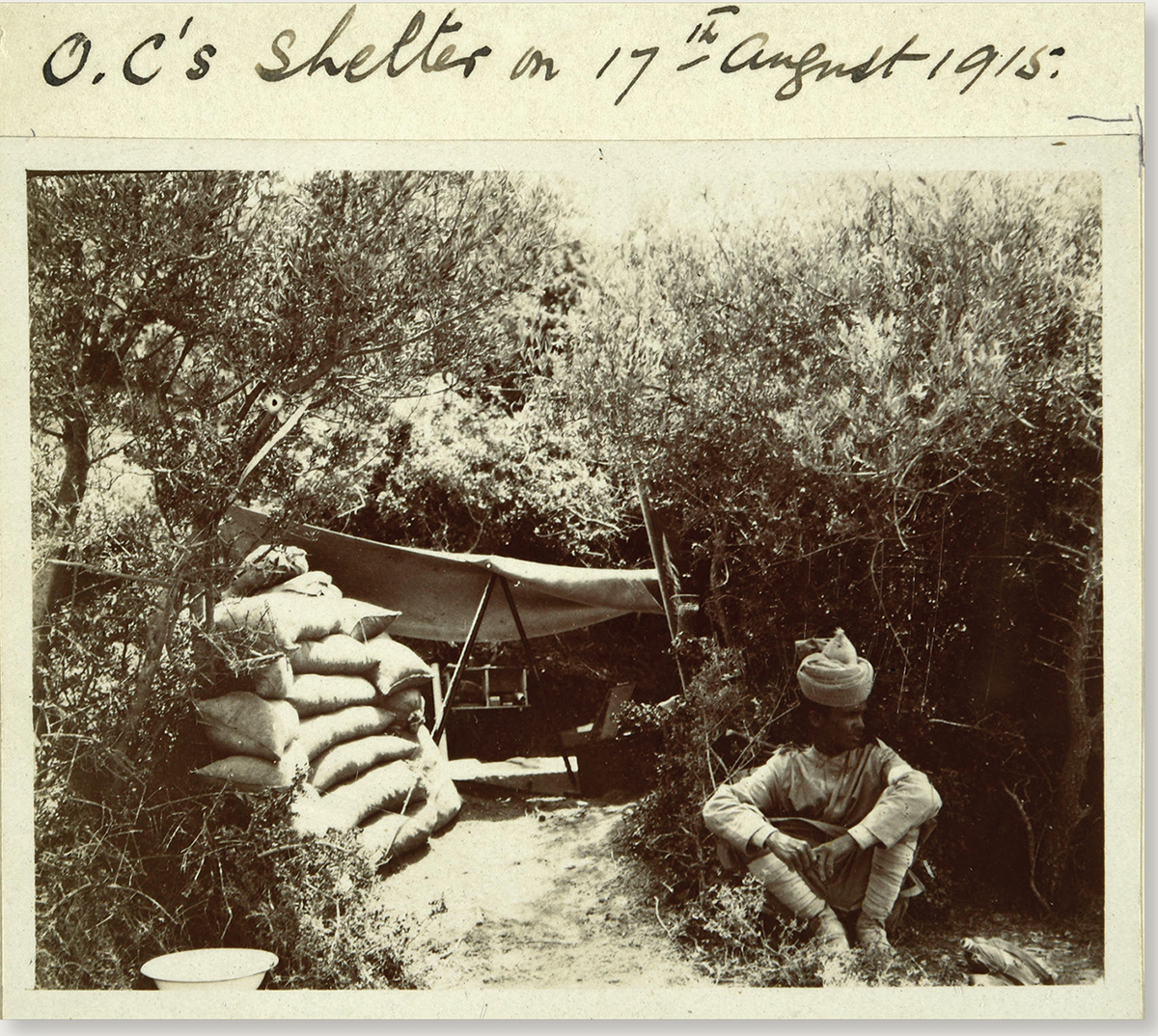

108th Indian Field Ambulance, Gallipoli, 1915.

Indian Field Ambulance hospital tents at Gallipoli.

Striking a blow against would-be strikers

Letter authorising the arrest of striking workers

19 FEBRUARY 1916

‘In the event of a strike taking place, the Police should at once deal with the pickets by warning, by removal, and by arrest if necessary.’

In war, the domestic policies of a government at home can be just as decisive as the tactical manoeuvres of an army on the battlefield. States have always reorganised themselves to achieve their war aims: for example, income tax was first introduced in 1799 to pay for war against France.

However, in the total wars of the twentieth century, the home front became a battlefield in its own right as the British state sought to direct all of Britain’s capacities towards its objectives.

To this end, conscription was introduced to fill the ranks of the armed forces, and in 1916 the Ministry of Munitions came into existence, charged with controlling the production of ‘munitions of war’ (not just guns and ammunition, but things like boots as well). The Ministry had oversight of thousands of factories, both publically and privately owned, and the countless workers producing munitions.

In 1914 the government had passed the Defence of the Realm Act, or DORA as it became known. This provided the government with the powers to rapidly bring regulations and penalties governing all parts of British life into law.

The regulations passed under DORA were diverse and multifarious – one even banned selling ‘fresh bread’, to ensure stale loaves were not wasted – but many of DORA’s central provisions made serious criminals out of those who were seen as being at odds with the realm, and provided for their imprisonment and trial by court-martial.

William Beveridge.

DORA’s Regulation number 42, which William Beveridge (future father of the welfare state) believed would allow policemen to arrest striking munitions workers, was one of DORA’s graver edicts, allowing for the arrest and trial of those attempting to:

‘Cause mutiny, sedition or disaffection … among the civilian population, or to impede or restrict the production, repair or transport of war material or any other work necessary for the prosecution of the war.’

This regulation, initially designed with saboteurs and traitors in mind, was nearly utilised a very different way: the Ministry of Munitions, as shown in this letter, sought to use it to paint as traitors patriotic trade unionists who engaged in a strike over wages and perceived union victimisation.

Relations between munitions workers, their employers and the government were occasionally tumultuous in the First World War. Most workers and trade unions supported the war effort and made agreements to help it, but disputes still occurred and sometimes led to strikes.

In February 1916, Tom Rees, secretary of the London district of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, fell foul of the somewhat uneasy wartime truce between the government and organised labour. Rees had agitated among workers at an Abbey Wood ammunition factory to strike over pay, and was subsequently arrested under Regulation 42 and set to stand trial at Bow Street Police court on 19 February.

Rees’ case became a cause célèbre among London trade unionists (200 attended his hearing) and the government feared industrial action would be taken in sympathy, particularly at Woolwich Arsenal, so they sought advice from their lawyers on whether a man on a picket line outside his place of work could be said to ‘impede the production of war material’. This was different from Rees’s crime, for he was accused of not following the proper process before calling a strike, as opposed to workers deciding for themselves. The law officers were sanguine about the government’s case, and so police were prepared to break the pickets.

In the end, though, this was not necessary. Rees’s hearing was moved to 21 February and no strike took place at Woolwich. Charges against Rees were eventually dropped, but his case shows just how close the pressures of war brought the government to curtailing that most basic of rights – of workers to withdraw their labour.

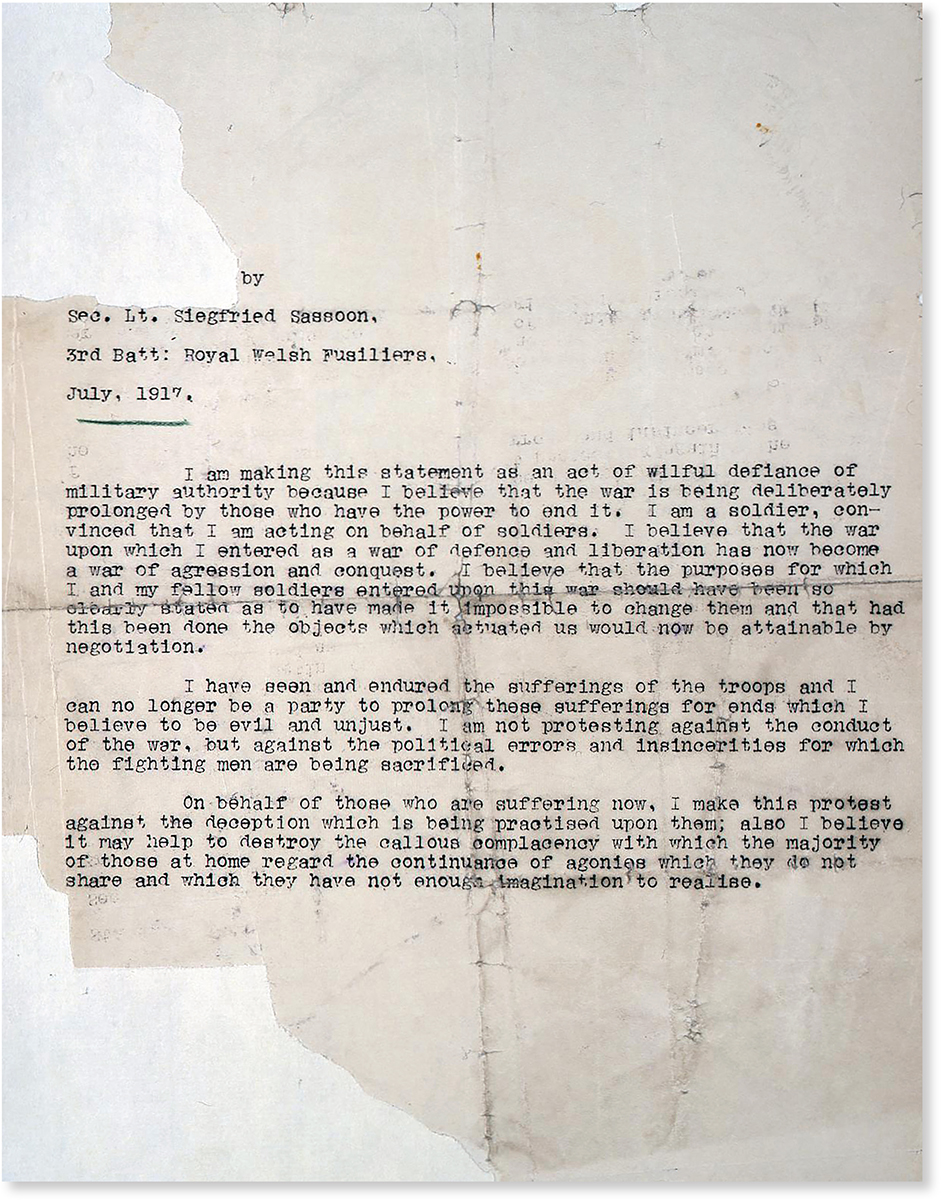

Siegfried Sassoon’s state of mind

Letter to the editor from Brigadier-General George Cockerill

20 JULY 1918

This letter was sent to the editor of The Nation, a leading British radical weekly newspaper, one week after it had published a poem by the well-known poet Siegfried Sassoon.

The poem in question is entitled ‘I Stood With The Dead’ and is a definite statement against the war: the last verse describes the poet standing among the corpses at the Front, lamenting that these men were being paid to stand in line and to kill and to die.

In response, the letter was sent to the editor by Brigadier-General George Cockerill in order to ascertain whether or not Sassoon was fit to be back at the Front. If he had written the poem in 1918, when it was published, the author reasoned, then there were grounds to believe that Sassoon should not have been sent back to France after his stay at Craiglockhart War Hospital.

To get to this point in the story, it is worth briefly looking at Sassoon’s service in the war. On 4 August 1914 he attested with the Sussex Yeomanry and by May 1915 he had been commissioned into the 3rd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers as second lieutenant. In the November of the same year he was posted to the 1st Battalion and sent to France. Once there, he became known for reckless acts of bravery, which eventually led to him being awarded the Military Cross in July 1916.

Throughout his military career, Sassoon had a few hospital stays, but it was the one in July 1917 that became the most significant, since the cause for this admission was stated as mental breakdown. Coinciding with this was Sassoon’s statement against the war – also pictured – in which he argued that he could no longer be party to the political mistakes and insincerities for which the men were fighting and suffering. He also wanted to highlight the atrocities to all at home, who he thought could not imagine the horrors of the Front. Instead of being court-martialled for this, Sassoon was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh to undergo convalescence – because surely such an outcry against the war could only come from someone whose mind had been influenced by the war and therefore he could not be held responsible for what he had said?

Concerned that his words would be seen as those of a mad man, Sassoon decided that he had to go back to the Front, whether he wanted to or not. In due course a medical board in November 1917 declared he was fit for general duties again, and by May 1918 he was back serving on the Western Front.

The fear that the poem published in The Nation was written during this time, when the war was still being fought, was that Sassoon’s mind might still be in chaos and that he could not be trusted with men’s lives, nor trusted not to spread his anti-war sentiment. This we will never know, for in his response the editor of the newspaper does not reveal how long the poem had been in his possession before he had printed it.

Siegfried Sassoon in uniform.

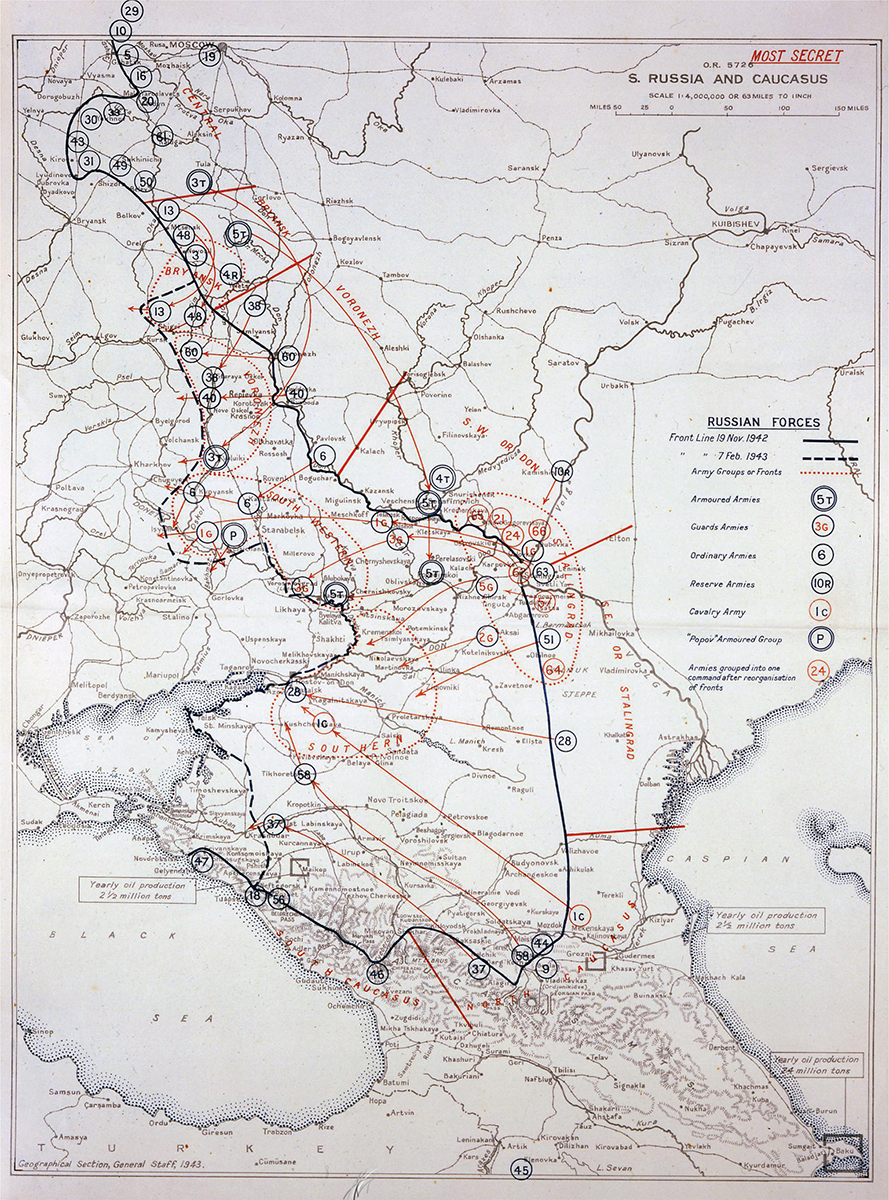

Should Stalingrad receive the George Cross?

A letter from three shorthand typists to Winston Churchill

24 SEPTEMBER 1942

This letter was sent to British prime minister Winston Churchill in September 1942, but was handled by the Foreign Office, which dealt with issues relating to other countries.

During the Second World War, Hitler had launched Operation Barbarossa in 1941 – an operation that was central to his plan to create an empire in the east. By the end of the year the severe Russian winter had stopped the advance, but a new German offensive in 1942 began in the south as Germany and the USSR fought over the control of Stalingrad. Possession of this city was of vital strategic importance to Germany because it would have given them control of oil reserves in the Caucasus area, the River Volga, and the immense psychological advantage of capturing the city named after the Soviet leader. By the close of July 1942, the Germans had successfully broken through to the outskirts of the city, and by September, when this letter was written, they were gaining more ground in harsh conditions with high casualties.

This letter is interesting because it captures the public mood in Britain in its appreciation of the bravery of the Soviet Army and the courage of the civilian population, and highlights the significance of the Battle of Stalingrad. After the example of the bravery demonstrated by the Maltese in 1940 against German and Italian forces, the island of Malta had been given the George Cross ‘for acts of the greatest heroism or for most conspicuous courage in circumstance of extreme danger’. Many people felt that the citizens of Stalingrad should also receive the same honour.

This polite, humble letter from three shorthand typists making its direct personal appeal to the prime minister was not uncommon. However, Anthony Eden, foreign secretary at the time, wrote to Winston Churchill in December 1942 and pointed out that according to the British Honours Committee, foreigners were not eligible for the award and the alternative Victoria Cross had never been given to a foreign town. Any lesser award, such as the Military Cross, ‘would be difficult to explain to the Russians … in view of the precedent of Malta’.

There was no exception made in the end to award the George Cross to the people of Stalingrad, though the city was honoured in a different way: in May 1944, a British delegation went to the Kremlin to present the city’s officials with the King’s Sword of Honour, a gift from George VI to the people of Stalingrad.

A statue of Lenin in the centre of the ravaged city of Staliingrad c. 1942–43.

Map showing the position of Russian forces during Operation Barbarossa.

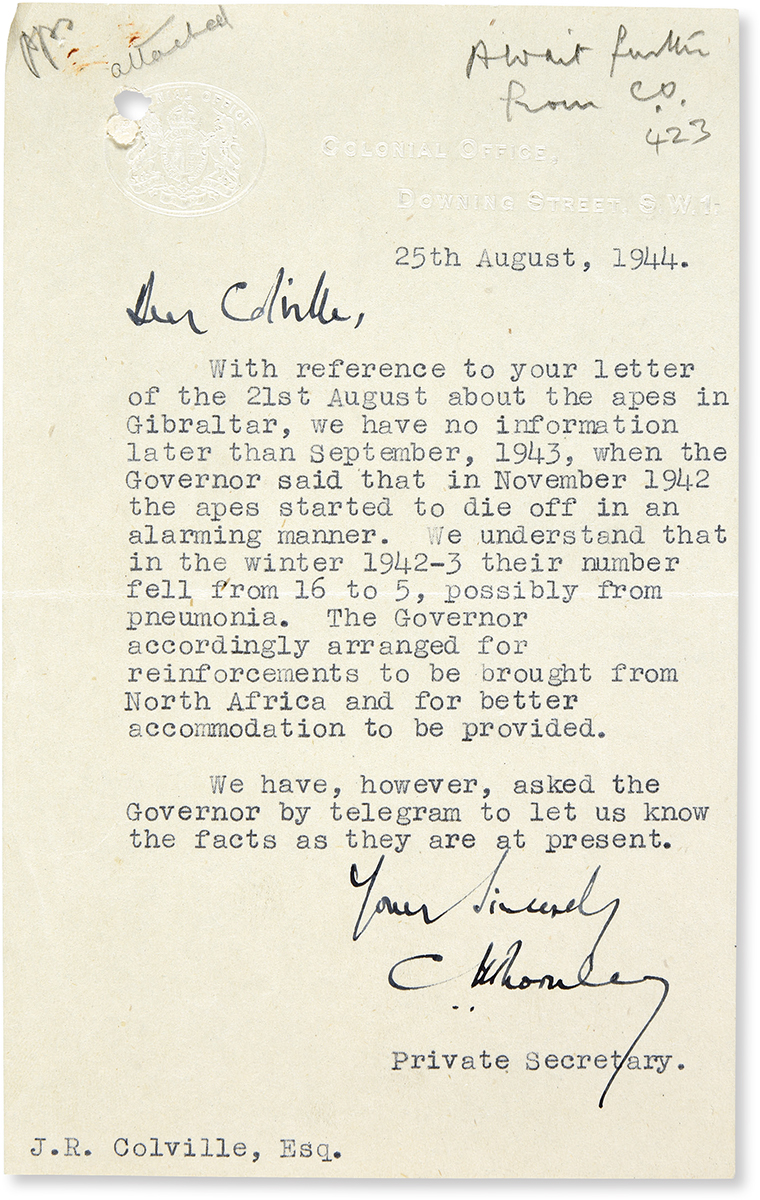

Churchill and the macaques of Gibraltar

Correspondence concerning ape welfare

1944

Situated on the southern coast of the Iberian Peninsula and guarding the entrance to the Mediterranean, the island of Gibraltar is home to the Barbary macaque, the only species of wild monkey found in Europe.

In 1713, Gibraltar was ceded to the British under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht. Soon after Britain had assumed control of the island, a belief emerged that Gibraltar would remain under British rule for as long as the Barbary apes were still there: when the apes left the Rock, the British would soon follow. The British Army soon established a garrison and naval base on the island and assumed responsibility for managing the macaque population. However, by 1913 the number of macaques had been reduced to single figures. To reverse the decline, therefore, the governor of Gibraltar, Sir Alexander Godley, quickly brought over eight young female apes from North Africa to replenish the population.

In 1915 the Gibraltar regiment appointed a ‘Keeper of the Apes’ who was given responsibility for the upkeep of the colony and maintaining a register. Updated every week, this register contained individual entries for each macaque, noting their names (many in honour of brigadiers, colonels and government officials and their wives), birthdays, weight, dietary requirements and offspring. The colony was also granted an official food allowance, which in 1944 amounted to £4 a month, which was used to supplement the monkeys’ natural diet with a variety of vegetables, fruit and nuts.

‘Scrufy’ developed dictatorial tendencies and had to be locked up to protect the local community.

Winston Churchill, who had visited Gibraltar, was keenly aware of the legend. In the early days of the Second World War, learning that the macaque population had dwindled to seven, he therefore issued instructions to have six females brought in quickly from Morocco.

A few years later, on 22 August 1944, Churchill asked for an update on the situation: ‘The Prime Minister is most anxious that they should not be allowed to die out, a possibility about which he has heard disquieting rumours. I believe there are dire prophecies about what will happen to Gibraltar if the apes vanished.’

In response, the governor of Gibraltar reported that the perilous position of the Rock apes was only a rumour. The number of macaques was currently fourteen, which included the six females imported from Morocco. He had also been reliably informed that the ‘marriage’ between ‘Pat’ and ‘Bessie’ had been recently consummated and that hopes were high for a new arrival to the colony.

In September, the prime minister issued a directive to the colonial secretary: ‘The establishment of the apes on Gibraltar should be twenty-four, and every effort should be made to reach this number as soon as possible and maintain it thereafter.’ To carry out his instructions, a troop transport was dispatched to North Africa and additional apes were brought to Gibraltar.

Churchill’s determination to prevent the apes from disappearing from Gibraltar was not based solely on superstition: he was aware of the symbolic importance of the apes and their effect on British morale. In the midst of war, their disappearance would have been seized upon by Hitler’s propaganda machine in an attempt to demoralise the British population.

Today, the population of the colony exceeds 300 animals, which are divided into five troops. For many, the Gibraltar Barbary macaques are considered to be the top tourist attraction in Gibraltar and a potent symbol of Britain’s sovereignty over the island.

Two comparative photgraphs showing the transformation of land near the Rock from a race course to an airport.

Keeping up Blitz spirits

Letter about the state of air-raid shelters

OCTOBER 1940

From September 1940 until the following May, London was dominated by the Blitz. This was the German bombing offensive – the name of which was derived from the German term blitzkrieg (lightning war) – that targeted the capital and other large ports and industrial centres across Britain.

Earlier in the same year the government had begun to build communal public air-raid shelters. These were designed to hold large groups of people and were an alternative for those living in built-up areas without gardens in which they could erect Anderson shelters.

Public shelters were constructed from brick and concrete and were identified by large black signs marked with a white ‘S’, so they could be easily found in the blackout. They were divided into different areas and furnished with wooden bunks.

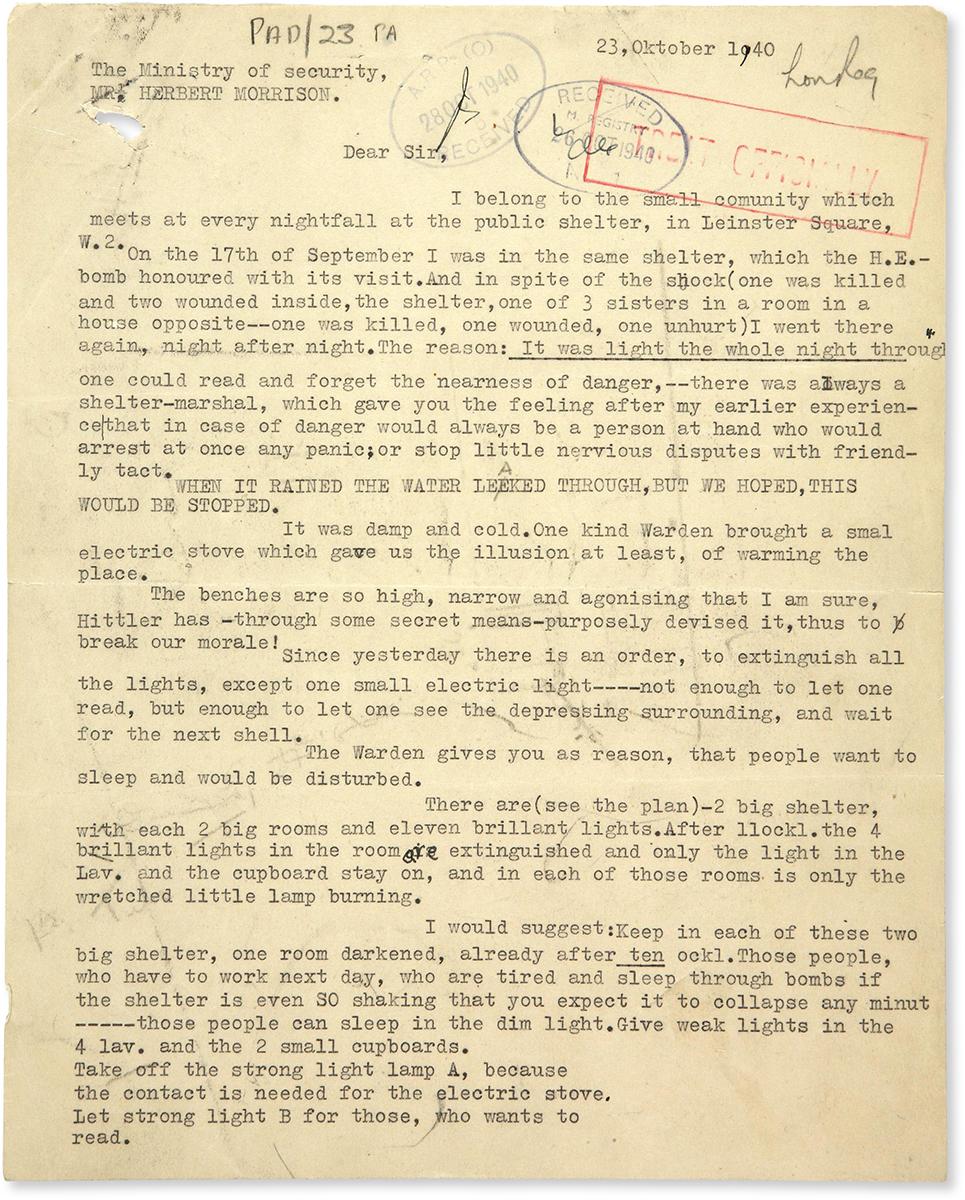

Jenny Fleming, who frequently sought shelter in a public air-raid shelter in Leinster Square, West London, wrote to the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, in 1940. In her letter she describes some of the hardships that she and others who used the shelter had to endure. Listed among her concerns are the issues of lighting, lack of reading material, the diminishing number of marshals, the leaking roof and the hard wooden benches provided for sitting and sleeping on. She writes that if the benches could be replaced with comfortable bunks, then the former could be used as exhibits in a ‘museum of instruments of torture’. Earlier in the letter she describes them as a ‘secret-means, purposely devised [by Hitler] to break our morale!’

Jenny’s letter is eloquently written, detailing each point in turn, and frequently suggests solutions to many of the problems. For example, her concern that all of the lights except for one small electric one are automatically extinguished is accompanied by a straightforward solution: she suggests there should be a room that is dimly lit for those who want to rest and can ‘sleep through bombs’ even if the shelter is shaking so much ‘that you expect it to collapse at any minute’, and another more brightly lit area for those who cannot sleep. Jenny has drawn a small diagram of the space to illustrate her idea, and swings from a slightly comical description of the heaviest sleepers to the more desperate feelings of those who stay awake throughout the night. ‘If you sit in this dim light the night through, waiting for bombs, feeling the tremors of the earth beneath your feet … such a night seems endless!’

She also writes passionately about the roof and how it needs to be made rainproof ‘at once!’, and describes the prison-like walls of the shelter and how they could be made ‘friendlier’ with posters of the British fleet of planes to ‘fortify morale’. She also comments on the kindness of the marshals and how more are needed. Throughout her letter, there is stoicism and a tendency to make the best of things, along with a concern for others and a strong desire to see the government make improvements, before ‘everybody’ becomes ‘depressed and miserable’.

What makes her letter all the more powerful are the beautiful illustrations of the different challenges she describes in the shelters. These add another dimension, bringing a vivid image of human suffering to the letter. The pictures of the woman sitting shivering under the umbrella inside the shelter, a look of misery on her face, or the woman wrapped up against the cold struggling to read in the dim light, make Jenny’s words more poignant.

From further documents within the file, including more illustrations, we learn that following the receipt of her letter Herbert Morrison spoke to Jenny on the telephone about the shelter’s conditions. He duly made arrangements to visit the shelter (although a further letter from Jenny suggests that this did not take place), and Jenny was able to raise further concerns about conditions, including the flimsy lavatory door and the dusty concrete floor that caused breathing difficulties for the shelter’s inhabitants.

Having fun in an air raid shelter.

The ‘Istanbul List’

The third exchange of German and Palestinian civilian internees

4 AUGUST 1944

The preliminary exchange of 46 Palestinians and 65 Germans took place on 12 December 1941. The American Embassy sent the list of Palestinians, designated by the German government, to the High Commissioner for Palestine in Jerusalem. The German party were escorted through Lebanon to Syria and were left by their escorts in Aleppo as they continued to the Turkish frontier on 13 December. The Palestinians arrived in Aleppo on 17 December, where they were provided with food and accommodation in the French cavalry barracks, arranged by the British Security Mission in Syria. They continued their journey and arrived in Haifa on 19 December to be met by representatives of the Jewish Agency. Information received from the American Embassy in Berlin indicated that the Germans were prepared to carry out further exchanges and the Palestinian government accepted this assumption. The Swiss took over the negotiations for future exchanges, with the Jewish Agency supplying addresses of those eligible for exchange.

Information was communicated through the Foreign and Colonial Offices to the German authorities through a Swiss legation in Berne; the British had no direct contact with the German government. Decisions about the eligibility of Jews to be put on a list of persons for exchange fell to the Jewish Agency in London. As news of the mass deportations and murder of Jews by the Nazis spread across the world, the guidelines were often reviewed and amended to include wives and children who were not born in Palestine or naturalised in Palestine and whose husbands came on immigration certificates. As this became apparent, the Jewish Agency relaxed the eligibility guidelines even further. However, many letters were still written to the Foreign Office pleading for relatives to be included on the list regardless of eligibility. Many were refused.

The second exchange was scheduled to take place on 1 November 1942 but the High Commissioner for Palestine sent a telegram to the Secretary of State for the Colonies informing him that the exchange would be postponed. This was because the date was inconvenient for the Turkish authorities, the train times did not suit and it was during the Turkish holiday. As well as this, there appeared to be a shortage of accommodation in Istanbul between 1 and 11 November.

The delay troubled the British since they didn’t want the Germans to think they were breaching the conditions of the exchange programme; it had been agreed that the date and place of exchange would be on 1 November in Constantinople. The exchange was confirmed on 8 October1942 and took place on 11 November when the trains passed each other in Istanbul; 137 Palestinians arrived from Vienna to Istanbul and were exchanged for 305 Germans. Transit visas were arranged by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

There were two more exchanges, the last of which took place in August 1944. This took over a year to plan and recorded twenty-six Palestinians, five returning residents and 251 ‘refugee immigrants’, of which 222 came from Bergen-Belsen. A further exchange was planned but was delayed by the suggestion that Germans include men of military age. Turkey was no longer considered as an option for travel and it was agreed to wait for a common frontier with Switzerland before another exchange could be considered. On 16 September 1944 all proposals for a fourth exchange were dissolved.

The total number of Jews on the Istanbul List numbered around 1,100. Many were untraced. The files indicate that 466 Palestinian Jews were saved as a result of this exchange programme.

An aerial view of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, taken in 1944.