Relations and relationships

Relations and relationships

Advice well received

Princess Elizabeth’s letter to her stepmother, Katherine Parr

SUMMER 1548

Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547 and by June the same year his widow, Katherine, had taken a new husband, Lord Admiral Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley. This hasty action worsened the relationship that Katherine and Thomas had with his brother, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, lord protector and governor of Edward VI. Nonetheless, Katherine still managed to secure the guardianship of Elizabeth, who resided with Katherine at her dower manors of Hanworth (West London) and Chelsea (inner London). This was an interesting situation, as it had been rumoured that only a few weeks prior to his proposal to Katherine, Thomas had asked Elizabeth to marry him and she had refused. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that Elizabeth was not ill disposed to Thomas’s attentions and that there had been some level of intimacy between them while she was living within the household.

Katherine was pregnant with her daughter, Mary, by December 1547 and scandalous rumours were circulating about the nature of the relationship between Elizabeth and Thomas by the first half of 1548. This letter was probably written in early summer 1548, since Elizabeth makes reference to the fact that Katherine was unwell at the time – perhaps as a result of the later stages of her pregnancy. Prior to writing this letter, Elizabeth had been sent to Cheshunt, Hertfordshire, to live in the household of Sir Anthony Denny, a close friend of the late Henry VIII – a move that would have both removed the opportunity for the relationship to develop between Elizabeth and Thomas and protected Elizabeth’s reputation.

The letter suggests that Katherine had given Elizabeth guidance about the dangers that could arise from gossip and that she was taking it on board: ‘I weighed it more deeper when you said you would warn of all evils that you should hear of me.’ Elizabeth clearly looked upon Katherine with respect and love and signed the letter: ‘Your highness’s humble daughter’, which provides an interesting insight into the nature of the relationship between these two royal women.

Katherine Parr

Although I could not be plentiful in giving thanks for the manifold kindness received at your Highness’ hand at my departure, yet I am some things to be born withal, for truly I was replete with sorrow to depart from your Highness, especially leaving you undoubtful of health, and albeit I answered little, I weighed it more deeper when you said you would warn me of all evils that you should hear of me, for if your grace had not a good opinion of me you would not have offered friendship to me that way, that all men judge the contrary, but what may I more say than thank God for providing such friends to me, desiring God to enrich me with their long life, and me grace to be in heart no less thankful to receive it, than I now am glad in writing to show it, and although I have plenty of matter, here I will stay for I know you are not quiet to read. From Cheston this present Saturday.

Your highness’ humble daughter

Elizabeth

Reassurance from a cast-off bride

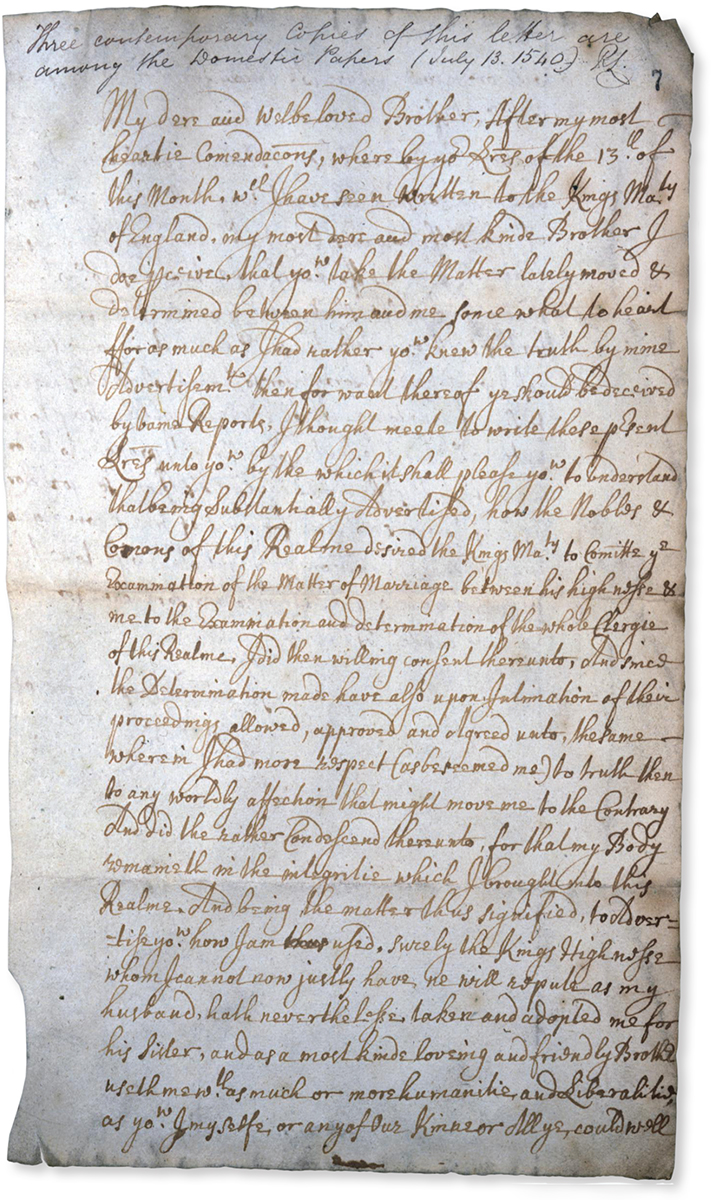

Letter from Anne of Cleves to her brother

21 JULY 1540

The fact that Henry VIII put aside his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, is well known, yet this letter, written from Anne to her brother, Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves (two former territories that are now part of the northern region of modern Germany and the Netherlands), sheds more light on the circumstances surrounding this peculiar situation. It was written in July 1540, shortly after the judgement was produced by the Convocations of Canterbury and York that declared the nullity of Anne’s marriage to the King.

In her childhood, Anne had been betrothed to François, heir to the duchy of Lorraine. However, this unofficial betrothal did not result in a formal marriage alliance, so Anne was put forward as a potential bride for Henry VIII in the late 1530s, in response to the contemporary political situation. Henry moved to ally himself with Cleves following his excommunication by Pope Paul III and after a defensive alliance had been formed by two key European rulers: François I of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. The lands owned by Anne’s father, Duke Johann (Duke of Jülich-Cleves 1490–1539), were strategically significant and her brother, Wilhelm, was recognised as Duke of Guelders (an historical duchy in the Low Countries) in 1538, which gave the territory coastal access – the importance of which would not have gone unnoticed by Charles V in the event of potential future conflict.

Duke Johann died in early 1539, leaving Wilhelm to deal with the marriage negotiations. Wilhelm was keen to promote a match and welcomed envoys from England to report on the suitability of a marriage. After Henry had settled on Anne, the government of Cleves assured him that the previous betrothal had not led to a binding marriage contract.

The pair duly wed, though Henry was unable to consummate his marriage to Anne – he was suffering from some form of sexual dysfunction at this time, which he ascribed to fears that the marriage was invalid as a result of Anne’s previous betrothal. Anne, however, confirms her virginity in the letter: ‘my Body remaineth in the integrity which I brought into this Realm.’

By this time the political situation had changed, making the need for an alliance with Cleves less pressing and, what’s more, Henry had fallen in love with one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, Catherine Howard. An ecclesiastical inquiry into the validity of the marriage was thereby called and although initially Anne refused to consent, she did eventually agree to the annulment.

Anne received a handsome settlement that also, as highlighted by the letter, defined her relationship with the King as that of brother and sister, although the settlement stipulated that her future communications with Cleves would be monitored. This Anne accepted reluctantly but it might explain the accepting tone of her situation in the letter and also her attempts to pacify Wilhelm, who she implied in the letter was displeased with the situation. Anne was in a precarious position, but in order to safeguard her settlement, it was important that she complied with Henry’s wishes.

The seals of Anne of Cleves, 9 July 1540.

21 July 1540

My dear and well-beloved Brother. After my most hearty commendations, whereby your letters of the 13th of this month, which I have seen written to the King’s Majesty of England, my most dear and most kind Brother I do perceive that you take the Matter lately moved and determined between him and me somewhat to heart for as much I had rather you knew the truth by mine advertisement than forward thereof you should be deceived by vain Reports. I thought meet to write these present letters unto you by the which it shall please you to understand that being substantially advertised, how the Nobles and Commons of this Realm desired the King’s Majesty to commit the examination of the matter of marriage between his highness and me to the examination and determination of the whole clergy of this realm. I did then willing consent thereunto. And since the determination made have also upon intimation of their proceedings allowed, approved and agreed unto, the same wherein I had more respect (as beseemed me) to truth than to any worldly affection that might move me to the contrary. And did the neither condescend thereunto, for that my Body remaineth in the integrity which I brought into this Realm. And being the matter signified, to advertise you how I am thus used. Surely the King’s Highness whom I can not now justly have me well repute as my husband, hath nevertheless taken and adopted me for his sister, and as a most kind, loving and friendly Brother useth me with as much or more humanity and liberality as you. I myself or any of our kin or all you could well wish or desire, where with I am for mine own part so well satisfied that I much desire that my good Mother and you should know this my state and condition, not doubt but when you shall thoroughly weigh all things you will so use yourself towards this Noble and good Prince, as he may continue his Friendship towards you which on his Highness’ behalf shall nothing be impaired or altered. for this matter, unless the fault should be in yourself, whereof I would be most sorry; for so it hath pleased his highness to signify unto me, which I have thought necessary to write unto you. And also that God willing I propose to lead my life in this realm, having his Grace so good Lord as he is towards me, lest for want of true knowledge of my mind and condition you might otherwise take this matter than you ought, and in other sort care for me then you have cause. Thus yours

Anna Duchess born of Cleves Gallic Guelder and Berger your loving Sister

One last love letter

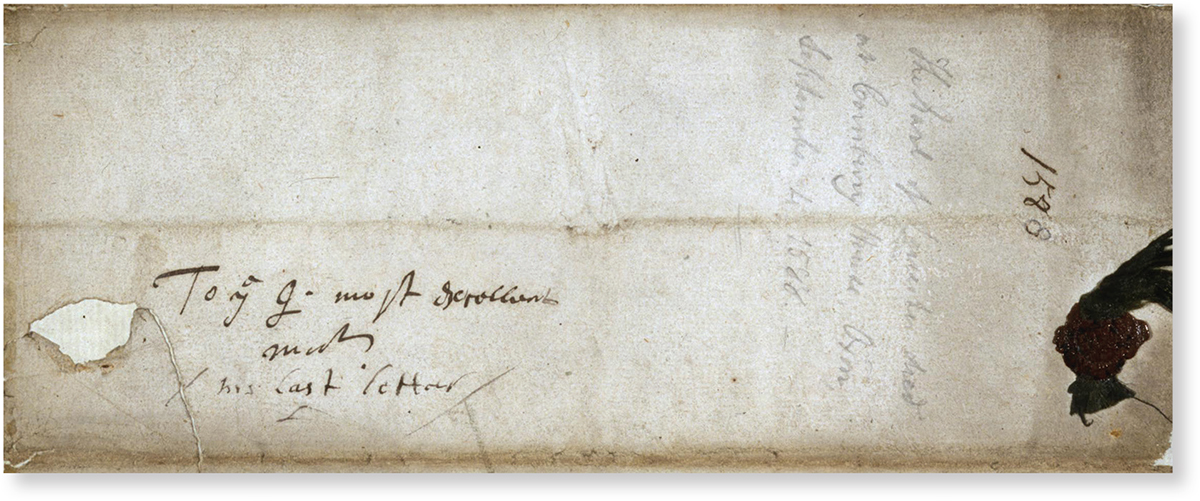

The final letter from the Earl of Leicester to Queen Elizabeth I

29 AUGUST 1588

When Elizabeth I died, her bedside casket contained her special personal treasures, among which was a document inscribed ‘his last letter’ that she had received from Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. The letter itself says little of import but its preservation and the inscription bear testimony to one of the greatest love affairs of all time.

Elizabeth and Robert had been close since childhood. They shared a tutor in Roger Ascham. Later, after the plot to put Jane Grey on the throne, when Robert was imprisoned in the Tower, his stay overlapped with that of Elizabeth, who was suspected of plotting against her sister, Mary. They were intelligent, charismatic and overwhelmingly ambitious individuals who shared a love of hunting, music and conversation. In another world or another time they would have been made for each other. Elizabeth was not, however, a woman to think the world well lost for love and she knew Dudley was vain, arrogant and ambitious (faults she possessed herself) and that England would never accept him as king.

Nevertheless, the two remained close: he had mortgaged his estates to lend her money when she needed it and nearly bankrupted himself building a special garden and elaborate entertainments for her visit to his home in Kenilworth, reputedly creating a second garden overnight when she pettishly complained she could not see the original from her room. In return, her marks of favour towards him provoked comment throughout Europe, and she wrote to him often, signing ‘As you know, ever the same. ER’.

A manuscript illustration of Elizabeth I in 1584.

Aware that marriage was not on the cards, Robert was not one to pine alone and he was married twice: first to Amy Robsart, whose death in mysterious circumstances caused a scandal; and eighteen years later to the Queen’s cousin Lettice Knollys – an unauthorised match that angered the Queen. She eventually forgave him and they remained close for the rest of his life. She herself never married, instead playing a complicated game of matrimonial politics among the royal houses of Europe and ending as the emblematic Virgin Queen.

The letter itself is short and formal. It is no outpouring of youthful passion, but this makes it all the more poignant: it is a letter between two old friends, both ageing and in increasingly poor health. A letter written to a woman who once stated ‘a thousand eyes see all I do’ is perforce a letter carefully crafted. Elizabeth called him ‘eyes’ and they used the device ‘öö’ in their letters to allude to this. Here, the device can be seen above the word ‘poor’. She has sent him medicine and, as the postscript indicates, a recent token. He sends his thanks, noting he is at Rycote in Oxfordshire – a mansion she knew and that they had visited together. There is significant subtext here.

Dudley’s last letter is a moving document. Whether or not Elizabeth and Leicester were lovers in a sexual sense is a matter for historical conjecture, but what this letter is undoubtedly testament to is a forty-year relationship – possibly Elizabeth’s closest. He died a few days after writing it. At the time this was attributed to malaria, although later historians have suggested he may have been suffering from stomach cancer. When Elizabeth was told of his death she locked herself in her room for three days, and went on to keep this last letter in her close personal effects until her own death fifteen years later, in 1603.

I most humbly beseech your Majesty to pardon your poor old servant to be thus bold in sending to know how my gracious lady doth, and what ease of her late pain she finds, being the chiefest thing in the world I do pray for, for her to have good health and long life. For my own poor case, I continue still your medicine and find that [it] amends much better than any other thing that hath been given me. Thus hoping to find perfect cure at the bath, with the continuance of my wonted prayer for your Majesty’s most happy preservation, I humbly kiss your foot. From your old lodging at Rycote, this Thursday morning, ready to take on my Journey, by Your Majesty’s most faithful and obedient servant,

Even as I had writ thus much, I received Your Majesty’s token by Young Tracey.

R. Leicester

“His last letter”

News from home

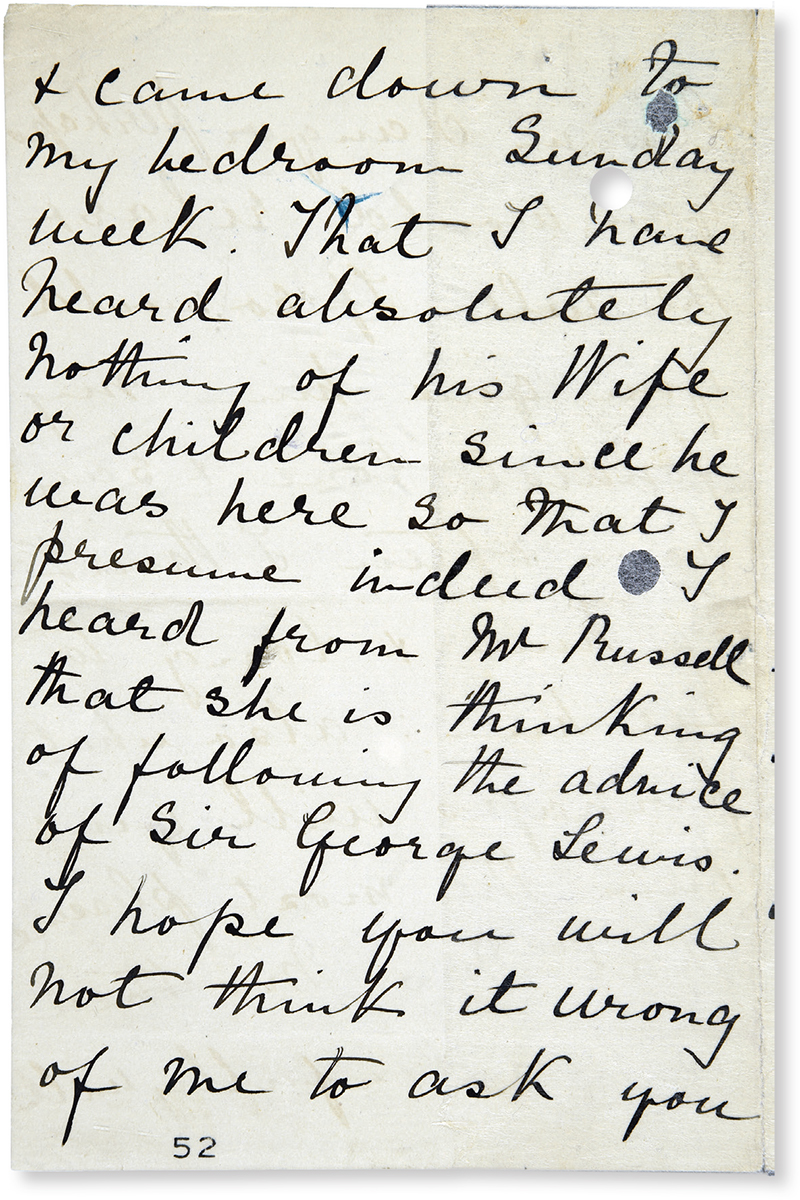

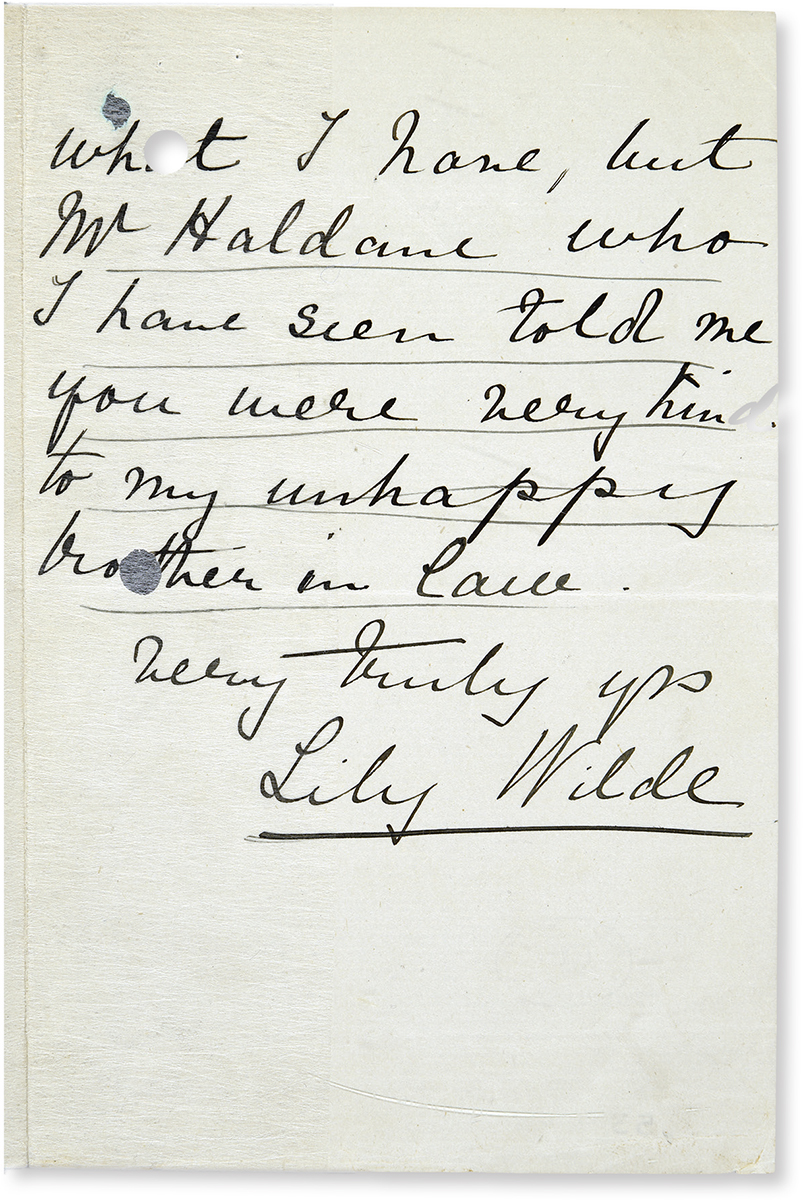

Letter from Lily Wilde to the governor of Reading Gaol

1897

The Marquis of Queensbury assembled an array of witnesses in his defence and the prosecution case collapsed. On 5 April 1895, Oscar Wilde was arrested and charged with gross indecency. The evidence from the libel case against Queensbury was turned around and used against Wilde. He was convicted at the Central Criminal Court and sentenced to two years in prison with hard labour.

On 18 February 1895, at the Albermarle Club in Piccadilly, John Sholto Douglas, Marquis of Queensbury, handed a card to the hall porter. The hall porter passed the card to its intended recipient. The card bore a short message, that, although open to some interpretation due to the handwriting, is generally considered to read: ‘For Oscar Wilde, posing sodomite’. This led Oscar Wilde to bring a libel case against Queensbury, who was the father of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas.

The case was heard in March 1895. The Marquis of Queensbury assembled an array of witnesses in his defence and the prosecution case collapsed. On 5 April 1895, Oscar Wilde was arrested and charged with gross indecency. The evidence from the libel case against Queensbury was turned around and used against Wilde. He was convicted at the Central Criminal Court and sentenced to two years in prison with hard labour.

During this period, many letters were sent to the governor of Reading Gaol by Oscar Wilde’s friends, his relatives, and by complete strangers. The content of these letters ranges from friends requesting permission to visit him to deal with his affairs to members of the public offering support and, in some cases, gifts.

This letter to the prison governor from Wilde’s sister-in-law, Lily Wilde, is particularly interesting and touching. Beginning with the rather strange request to return his brother’s waistcoat, it ends with the poignant plea to pass on her love to Oscar, along with a message regarding the health of his mother. We can have no idea whether Wilde saw this letter or knew of it or its contents, yet it seems unlikely as the letter was sent to the governor and not to Wilde. We also don’t know whether the waistcoat was returned as requested.

The collection of The National Archives holds other key records of this famous case, including the card that was handed to the hall porter at the Albemarle Club. In July 1896, Oscar Wilde made a petition from his cell in Reading jail to the Home Secretary for early release. The petition is also held in The National Archives and gives a stark account of Oscar Wilde’s time in gaol and to the solitary confinement to which he was subjected. He was bankrupt, suffering failing health, and clearly at the limit of what he could bear. However impassioned this petition, though, it failed: Oscar Wilde remained in jail for almost another year, completing the entirety of his sentence. Following his release in 1897 he left for France, where he died in 1900.

Oscar Wilde, prior to his imprisonment.

146 Oakley St

Chelsea

Monday

Dear Sir

My brother in law Mr Oscar Wilde on the day of the verdict wore his brother’s waistcoat in place of his own. Would you be so kind as to send it to me. I will forward the right one. I do not know if you would extend your kindness to give a small message from me but as I am expecting my confinement shortly & one’s life is always more or less in danger perhaps you would relax the rule. If so would you give him my fondest love and say how often I think of him & long to see him: also what perhaps will give him the most pleasure that his Mother is wonderfully well & came down to my bedroom Sunday week. That I have heard absolutely nothing of his Wife or children since he was here so that I presume indeed I heard from Mr Russell that she is thinking of following the advice of Sir George Lewis. I hope you will not think it wrong of me to ask you what I have, but Mr Haldane who I have seen told me you were very kind to my unhappy brother in law.

Very truly yrs

Lily Wilde

Enforced emigration to Canada

A father’s desperate letter to Stepney Barnardo’s children’s home

20 JANUARY 1911

This letter was written in response to a letter Rowe had received from Barnardo’s children’s home in Stepney informing him that his daughters, Hilda Kate and Eva May (aged twelve and sixteen respectively), were likely to be selected to go with the next party of children to Canada, where they would be received into a Canadian family provided they ‘behaved well’.

Both girls had been resident in the Dr Barnardo’s Girls’ Village Home, Barkingside, Ilford, since 1907 when they were committed at the Petty Sessional Court in Southampton, under the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act 1904. Court documents note that their mother had died in November 1905 and that their father, a painter, was said to be of ‘lazy and drunken habits’. In March 1906 he was sentenced to three months’ hard labour for having neglected his children. The neglect, however, was subsequently resumed upon his release, and in November 1907 he was sentenced to a further six months’ hard labour for repeating the crime – the children, who had undergone ‘the severest privations’, having been found to be living ‘under the most wretched conditions and in a state bordering on starvation’.

This case was typical of many of those of children who were sent overseas at the beginning of the twentieth century, although British child-emigration schemes had been in operation since as early as 1618 and continued as late as 1967. During this period it is estimated that some 150,000 children were sent to the British Colonies and Dominions, most notably America, Australia and Canada, but also Rhodesia and New Zealand. Many of the children were in the care of the voluntary organisations that arranged for their migration. Child emigration peaked from the 1870s until 1914, and some 80,000 children were sent to Canada alone during this period.

Mid-nineteenth century Victorian Britain did not smile upon the poor – and the big cities were full of them. Those who swelled the slums were people who had flocked to the industrialised cities from the country in search of jobs in factories and the docks. Many were Irish refugees from the Potato Famine of 1845–1849, and all of them struggled to eke out a marginal existence. Food was scarce, sickness and epidemics of cholera and smallpox were rife and housing grew more and more scarce. In the 1860s, houses were demolished to make way for the railways and new ones were not within the reach of the poor. By the 1880s, the housing shortage had become chronic, with more and more people crowding into the tenements and slum landlords making huge profits. Crime and lawlessness flourished, and in this hostile environment poor children grew up with little food, no education, sometimes abandoned by their parents and often exploited for their work.

Into the morass stepped several philanthropists, most of them imbued with an evangelical mission to spread the word of God and rescue the poor from sin. They set to work with energy and dedication, establishing shelters for the destitute, and schools and homes for their young. However, the stream of those in need was never-ending and with the rise of unemployment in the late 1860s, the charities and the Poor Law Unions began to send people to Canada, freeing up space in the workhouse for more people.

Dr Barnardo was probably the biggest player in child-migration schemes in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the result that by the early 1900s Canadians were calling all child emigrants, no matter where they originated, ‘Barnardo boys’. By the time of his death in September 1905 nearly 16,000 children had been sent by him to Canada, according to an article reporting on his funeral in the Illustrated London News. In fact, the true figure was 18,172. Furthermore, by 1939 more than 30,000 children had been sent to Canada by his organisation.

The aim of child migration was often to increase the population within the Colonies, and to improve labour and productivity there. Although most schemes were presented as being for the benefit and welfare of the child, few actually took the feelings of the children into account.

Sadly, it would seem that the Rowe girls never managed to see their father again after they departed Southampton for Quebec in Canada on board the SS Sicilian, on 29 June 1911, with more than 150 other children from Dr Barnardo’s homes – all destined for homes in Peterborough, Ontario.

371 Parkwood Road

Southampton

Jan 22 [1911]

Sir

I was surprised to receive a letter from you telling me you were sending my little girls to Canada which I do not approve of and if there [are] any means of stopping it I shall do so. I think they are quite [sic] far enough away from me now. I called on your manager at the Southampton Branch on Saturday and he told me when there [sic] time was up they would be left there and that means to say I shall never see the children again. I consider myself I have been punished quite enough.

I shall never be able to save the money for them to come back. I cannot pay my way now work being so very slack. I shall endeavour to see the Magistrates who made the order. I think it is most cruel to be sent so far away from there [sic] father and friends that loves them so dear.

I am Sir

Yours truly

W G Rowe

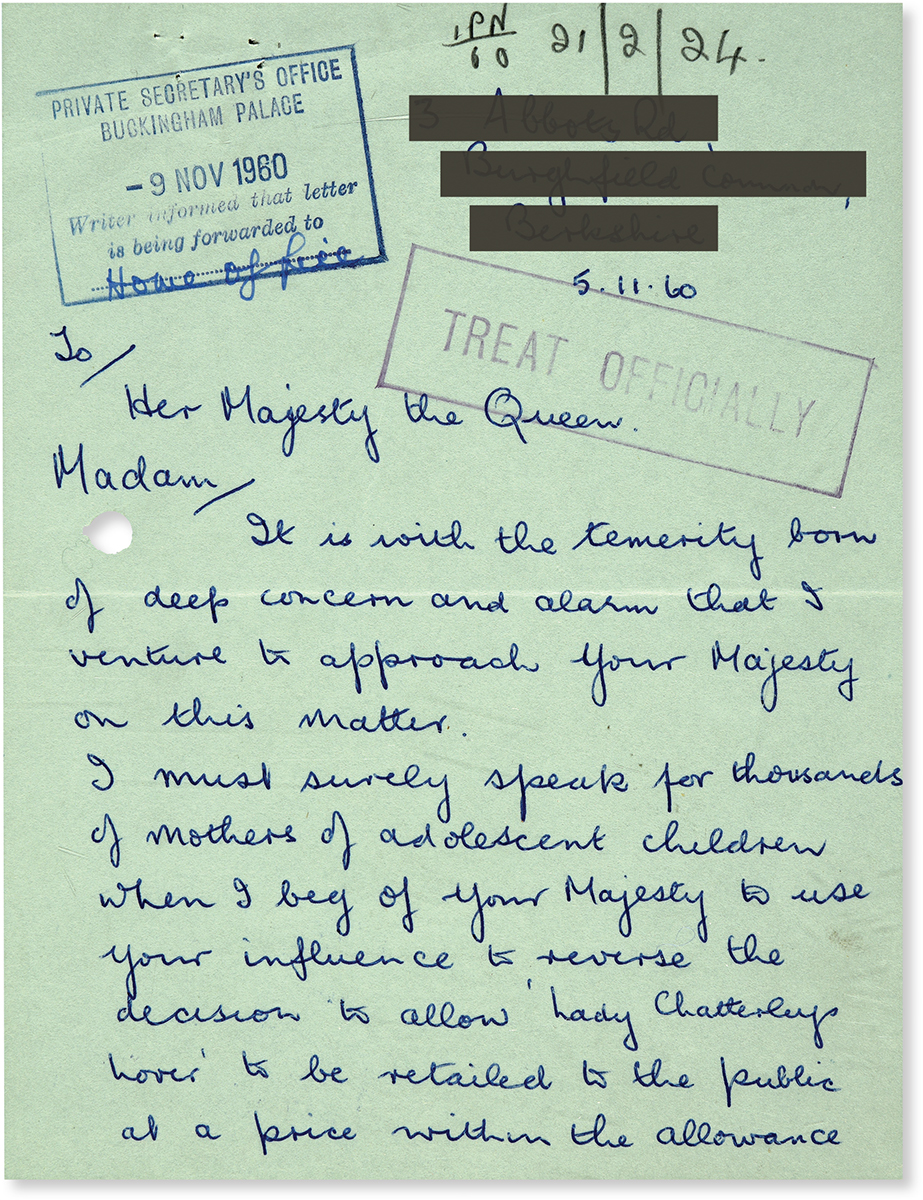

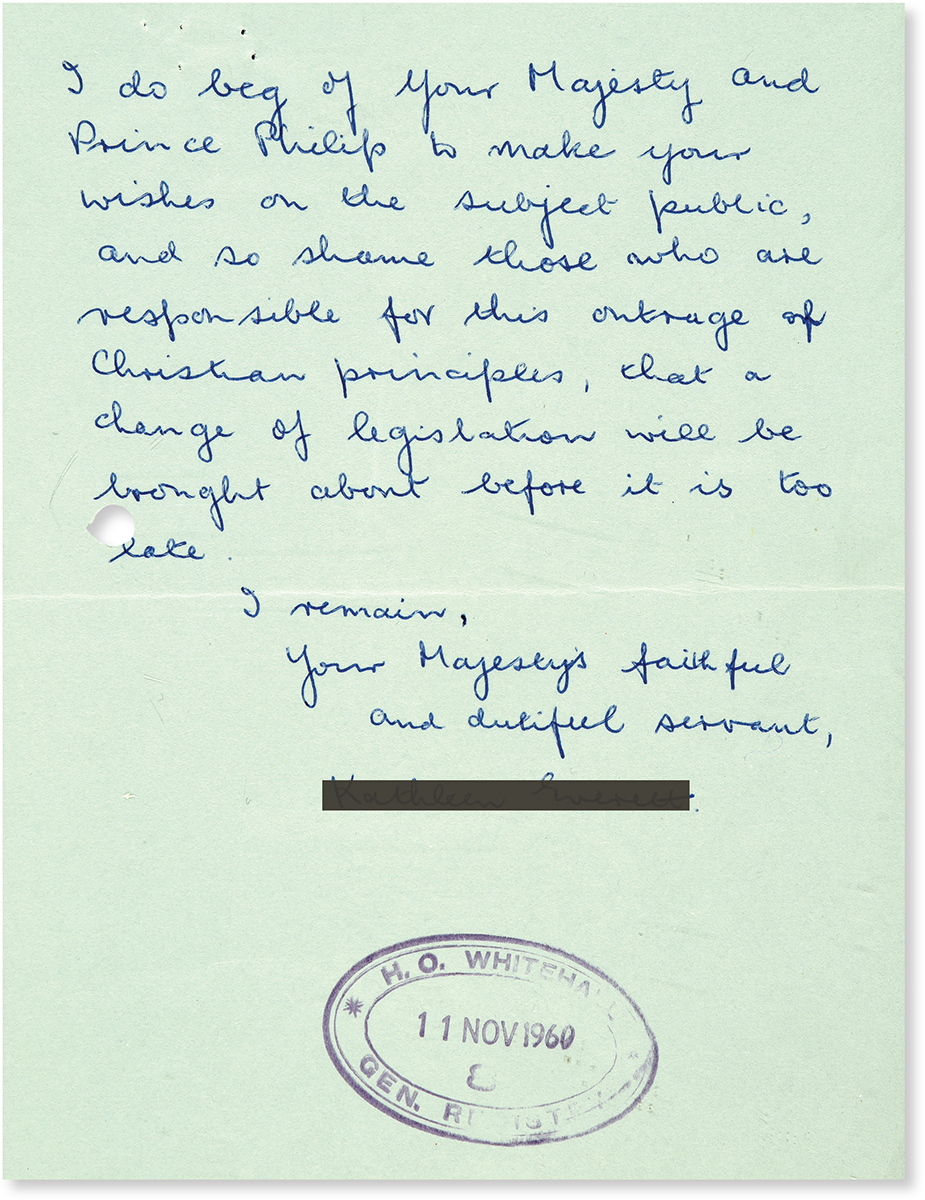

‘An outrage of Christian principles’

An unexpurgated publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover

5 NOVEMBER 1960

Despite having been published in its entirety in countries around the world since the 1920s, by 1960 only the expurgated version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover – known as The First Lady Chatterley – by DH Lawrence was available to buy in the United Kingdom.

Describing the affair between a woman and her husband’s gamekeeper, the theme, descriptions and language of the full version of the book were still considered by some to be shocking at the beginning of the 1960s.

Following revisions to the Obscene Publications Act in 1959, however, Penguin Books Limited took the decision to publish the unexpurgated version of the book in the UK. They printed 200,000 copies, which they proposed to retail at 3s 6d – a very affordable price. This bold move led to the famous trial. Charged with publishing an ‘Obscene Article’, the trial of Penguin Books took place at the Old Bailey between 20 October and 2 November 1960.

The Obscene Publications Act 1959 deemed a book to be obscene if it could be proved that its content could tend to deprave and corrupt readers. It would not be deemed to be an obscene publication if it were justified as being for the public good on the grounds that it was in the interests of science, literature, art or learning. In this case, the prosecution based its argument on the opinion that Lady Chatterley’s Lover was obscene and could corrupt and deprave. The defence argued that it was a work of art justified as being for the public good, and called thirty-five witnesses – including famous authors and academics – to testify to the artistic and moral value of the book. The prosecution called no witnesses. After hearing all of the arguments and deliberating for three hours, the jury returned a unanimous verdict of not guilty. Penguin Books went on to publish Lady Chatterley’s Lover in full; all 200,000 copies sold out on the first day.

The collection of The National Archives contains the papers of the prosecution – the papers of the Director of Public Prosecutions. This includes preparatory papers and notes, the full transcript of the trial, and meticulously underlined copies of the books, highlighting specific passages of a sexual nature.

As well as the official records of the prosecution, The National Archives has many letters from members of the public, horrified at the outcome of the trial and the ‘threats’ posed to society by the publication. These were handled by the Home Office and many were addressed to the Home Secretary. However, this example shows that some were not satisfied with merely contacting a politician and instead appealed directly to the Queen, imploring her to intervene so that the decision might be overturned.

The majority of these letters deal with the fear of moral corruption and give a fascinating insight into the opinions of some quarters of the public at that time, as well as raising an interesting question of how much opinions on the nature of morality and taste have moved on since 1960.

Sir Allen Lane, the managing director of Penguin Books, with a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Address redacted

5.11.60

To

Her Majesty the Queen

Madam,

It is with temerity born of deep concern and alarm that I venture to approach your Majesty on this matter.

I must surely speak for thousands of mothers of adolescent children when I beg of your Majesty to use your influence to reverse the decision to allow ‘Lady Chatterleys Lover’ to be retailed to the public at a price within the allowance of youths and girls still at school.

The depravity of this book is unspeakable, and with your sheltered upbringing in a Christian home Your Majesty cannot conceive the immoral situations which will be put before innocent minds. Many a girl, who, reading out of a desire to be up-to-date, will have her approach to marriage warped, and boys of the age of your son, the Prince of Wales, and mine, a year older, may learn such things from school fellows that well refute the sanctity of the body, and turn healthy inquiring minds to furtive, lewd and immoral pursuits.

I do beg of Your Majesty and Prince Philip to make your wishes on the subject public, and so shame those who are responsible for his outrage of Christian principles, that a change of legislation will be brought about before it is too late.

I remain,

Your Majesty’s faithful and dutiful servant,

Name redacted

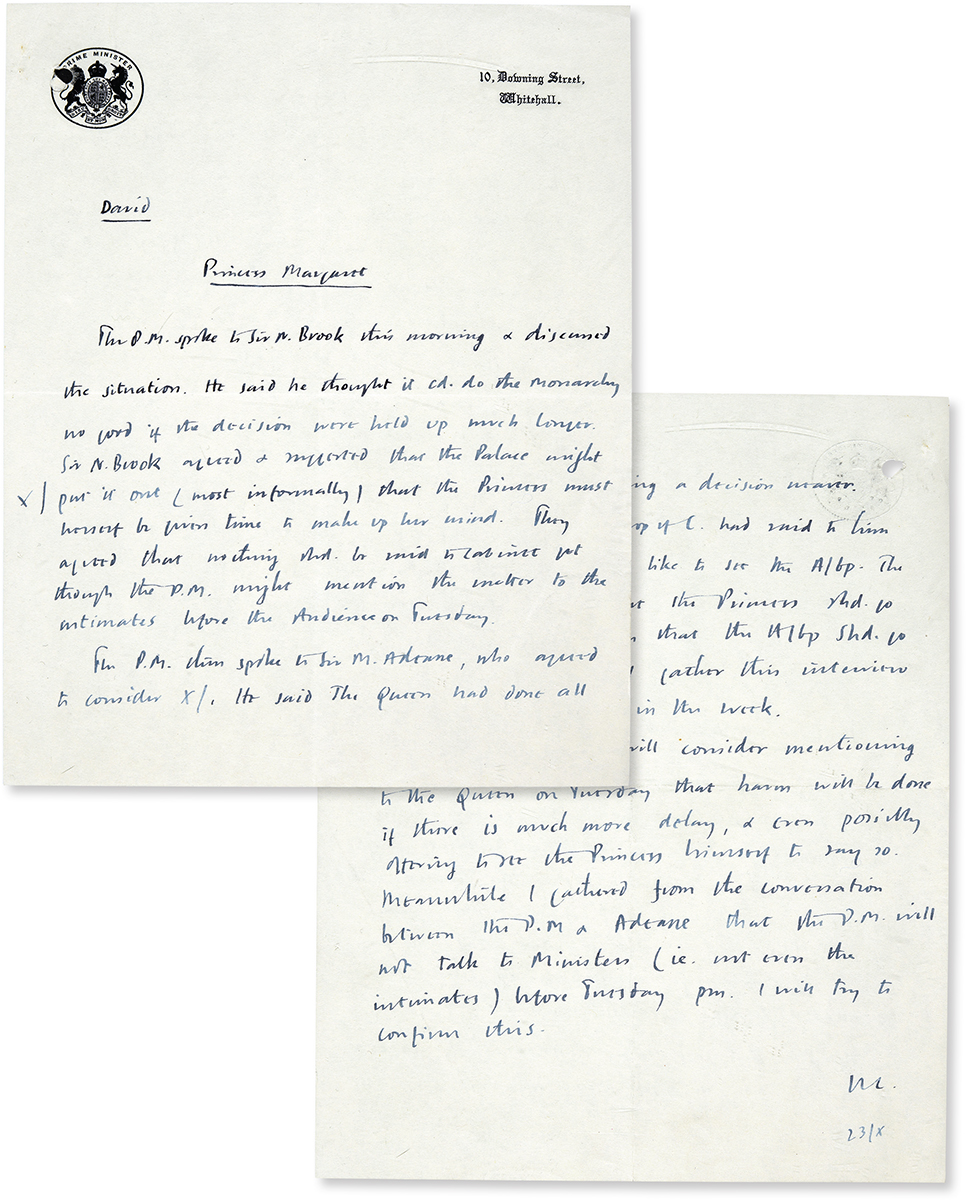

Time to make up one’s mind

Princess Margaret’s marriage correspondence

SUMMER 1955

Royal marriages can be a time for national celebration, with street parties bringing communities together, families crowding around television screens, and flags fluttering between street lamps. They can also cause great upheaval and crises that strike to the very core of Britain’s constitutional monarchy. Edward VIII’s marriage to the American divorcee Wallis Simpson is a case in point, since it forced the abdication of the young king in 1936. Seventeen years later, his niece Princess Margaret also found herself in an unfortunate position – in the eyes of the British establishment – when it came to falling in love.

Group Captain Peter Townsend, an RAF flying ace who led a squadron of Hawker Hurricane pilots throughout the Battle of Britain, had been made comptroller of the Queen Mother’s restructured staff at Clarence House following the death of George VI. Townsend had previously served as equerry to the king and by April 1953 the thirty-eight-year-old father-of-two had divorced his wife and proposed to the twenty-two-year-old princess.

Once again the Church of England’s opposition to divorce was a barrier, as were the views of Winston Churchill’s Conservative government. In addition, Queen Elizabeth II’s consent was required under the Royal Marriages Act of 1772. The situation was further complicated by the fact that Margaret’s sister had yet to be crowned, with the coronation being organised for June. Indeed, it was at the coronation at Westminster Abbey that the relationship became public in somewhat subtle circumstances: Margaret was seen brushing some fluff off Townsend’s uniform as she waited for her carriage.

By the summer of 1955 Anthony Eden was prime minister – himself having divorced and remarried – and studies were underway to determine whether an Act of Parliament could eliminate the need for the Queen to give permission for the marriage if Margaret, and her future children, were to be removed from the line of succession. For her part, the Queen was reportedly supportive of the proposal.

Princess Margaret with Peter Townsend.

On 15 August Margaret wrote to Eden from Balmoral Castle, acutely aware of the growing intensity in press speculation as she approached her twenty-fifth birthday. She assured the prime minister she would not see Townsend until she returned to London in October. Townsend would then be taking his annual leave and Margaret wrote that she had to see him in this period as: ‘It is only by seeing him in this way that I feel I can properly decide whether I can marry him or not.’ Margaret saw the decision as hers to make rather than anybody else’s, and informed Eden of this in clear terms. However, she was also ‘particularly anxious that whatever may happen, may not cause any embarrassment to you personally, or to the government’.

In the end, Margaret called off the engagement on 31 October, citing her overriding duty to the Commonwealth and to the teachings of the Church. In May 1960 her marriage at Westminster Abbey to photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones, later Earl of Snowdon, was the first royal wedding to be televised. The couple’s social circle included many of the stars of the 1960s and provided plenty of copy for tabloid headline writers before the pair separated in 1978.

David

Princess Margaret

The P.M. spoke to Sir N Brook this morning & discussed the situation. He said he thought it cd. do the monarchy no good if the decision were held up much longer. Sir N. Brook agreed and requested that the Palace might put it out (most informally) that the princess must herself be given time to make up her mind. They agreed that nothing shd be said in Cabinet yet though the P.M. might mention the matter to the intimates before the Audience on Tuesday.

The P.M. thus spoke to Sir M. Adeane, who agreed to consider. He said The Queen had done all that was possible to bring a decision nearer. The P.M. said the Archbishop of C[anterbury] had said to him that the Princess wd. like to see the A/bp. The P.M. had advised that the Princess shd. go to Lambeth rather than that the A/bp shd go to Clarence House. I gather this interview will take place later in the week.

I think the P.M. will consider mentioning to the Queen on Thursday that harm will be done if there is much more delay, & and even possibly offering to see the Princess himself to say so. Meanwhile I gathered from the conversation between the P.M. & Adeane that the P.M. will not talk to Ministers (ie not even the intimates) before Tuesday pm. I will try to confirm this.

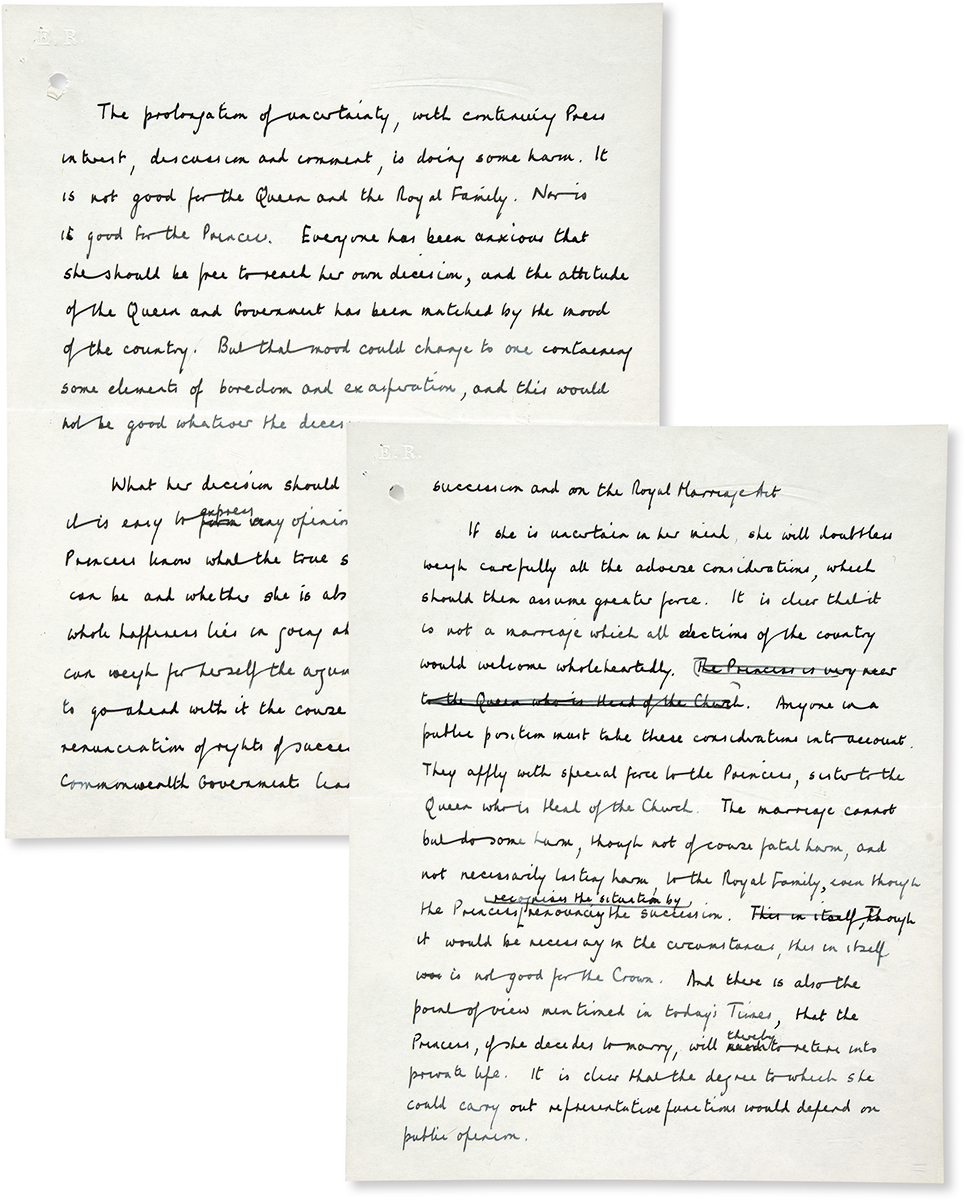

The prolongation of uncertainty, with continuing Press interest, discussion and comment, is doing some harm. It is not good for the Queen and the Royal Family. Nor is it good for the Princess. Everyone has been anxious that she should be free to reach her own decision and the attitude of the Queen and Government has been matched by the mood of the country. But that mood could change to one containing some elements of boredom and exasperation, and this would not be good whatever the decision.

What her decision should be is not a matter on which it is easy to express my opinion. How can anyone but the Princess know what the true state of her feelings towards T can be and whether she is absolutely convinced that her whole happiness lies in going ahead with this marriage. She can weigh for herself the arguments against. If she decides to go ahead with it the course of action is pretty clear: renunciation of rights of succession: consultation with Commonwealth Government leading to legislation on the succession and on the Royal Marriage Act.

If she is uncertain in her mind she will doubtless weigh carefully all the adverse considerations, which should then assume greater force. It is clear that it is not a marriage which all sections of the country would welcome wholeheartedly. Anyone in a public position must take these considerations into account. They apply with special force to the Princess, sister to the Queen who is Head of the Church. The marriage cannot but do some harm, though not of course fatal harm, and not necessarily lasting harm, to the Royal Family, even though the Princess recognises the situation by renouncing the succession. Though it would be necessary in the circumstances, this in itself is not good for the Crown. And there is also the point of view mentioned in today’s Times, that the Princess, if she decides to marry, will thereby retire into private life. It is clear that the degree to which she could carry out representative functions would depend on public opinion.

My Dear Prime Minister,

I am writing to tell you, as far as I can, of my personal plans during the next few months.

I am doing so because I am particularly anxious that whatever may happen, may not cause any embarrassment either to you personally, or to the Government.

During the rest of August and all September I shall be here at Balmoral and I have no doubt that during this time – especially on my birthday on August 21st – the press will encompass every sort of speculation about the possibility of my marrying Group Captain Peter Townsend.

I am not going to see him during this time but in October I shall be returning to London, and he will then be taking his annual leave – I do certainly hope to see him while he is there, although I well know this will provoke the press to still further enquiries & guesses.

But, it is only by seeing him in this way that I feel I can properly decide whether I can marry him or not.

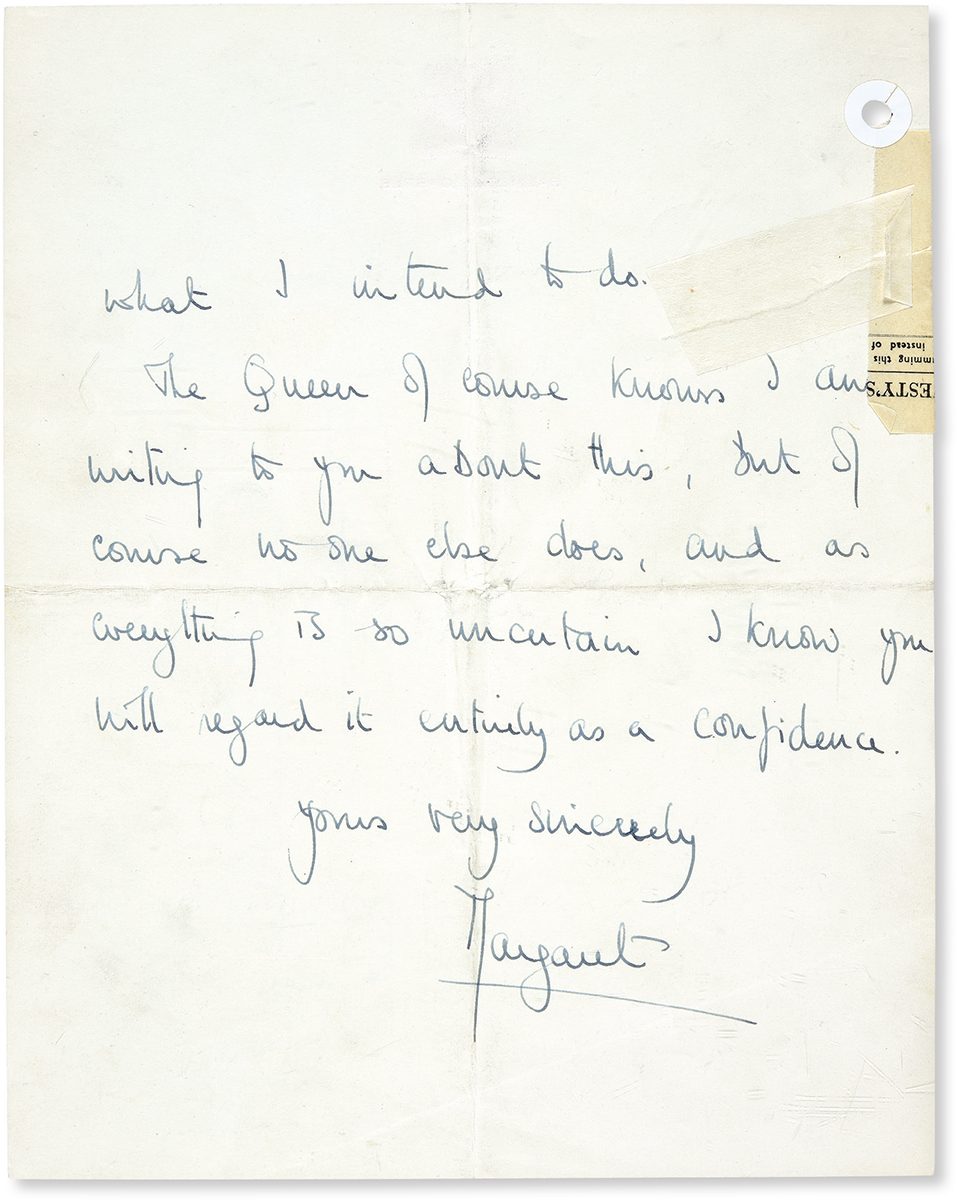

At the end of October or early November I very much hope to be in a position to tell you and the other commonwealth Prime Ministers what I intend to do.

The Queen of course knows I am writing to you about this, but of course no one else does, and as everything is so uncertain I know you will regard it entirely as a confidence.

Yours very sincerely

Margaret