Chapter 3

Star Student

George woke up in the hospital with tubes in his arms, needles in his stomach, and an oxygen tube up his nose. He could barely see his mother beside him. “Mom,” he whispered, “did I do something wrong?” Dorothy started to weep.

Had he not been thrown out of the car, George would have died. During his two weeks in the hospital and the long recovery afterward, he changed his mind about being a race-car driver. Now he wanted to do something meaningful with his life.

He missed his final exams, but Thomas Downey High School awarded him a diploma anyway. Little did they know the former greaser was making plans for college. When he was well enough, George enrolled in Modesto Junior College and studied sociology, anthropology, literature, and astronomy. For the first time, George became a great student. Soon he was ready to move on to a four-year college.

John Plummer encouraged George to apply to the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Haskell Wexler was a Hollywood cinematographer who knew George through the racing circuit. He offered to help George. The film school at USC was top-notch. George had always loved photography. Now he wanted to make movies. George Sr. wasn’t happy about the idea—it didn’t sound very practical—but he agreed to pay the tuition.

George arrived at USC in 1964. The school’s motto was “Reality Stops Here.” It meant that anything was possible, that dreams started there.

At USC, George studied English, astronomy, history of film and animation, and drama. He knew he had found his calling. He made his first short film, Look at Life, in 1965. George quickly became part of the elite group of students who were considered the best in the class. He and his friends edited films at night because they were allowed only two hours a day on the Moviola editing machine. George loved cutting shots together to make meaning out of pictures. Through editing he could conceal some of his weaknesses as a beginning filmmaker. He didn’t yet understand how to write strong characters or work with actors to bring about better performances.

Student films at USC were shown in public screenings. George’s family came from Modesto to see his. George Sr. noticed that any time one of George’s films came up, the “long-haired hippie kids” in the audience whispered, “Watch this one, it’s George’s film!” He said to his wife, “I think we put our money on the right horse.” Once again George had surprised him.

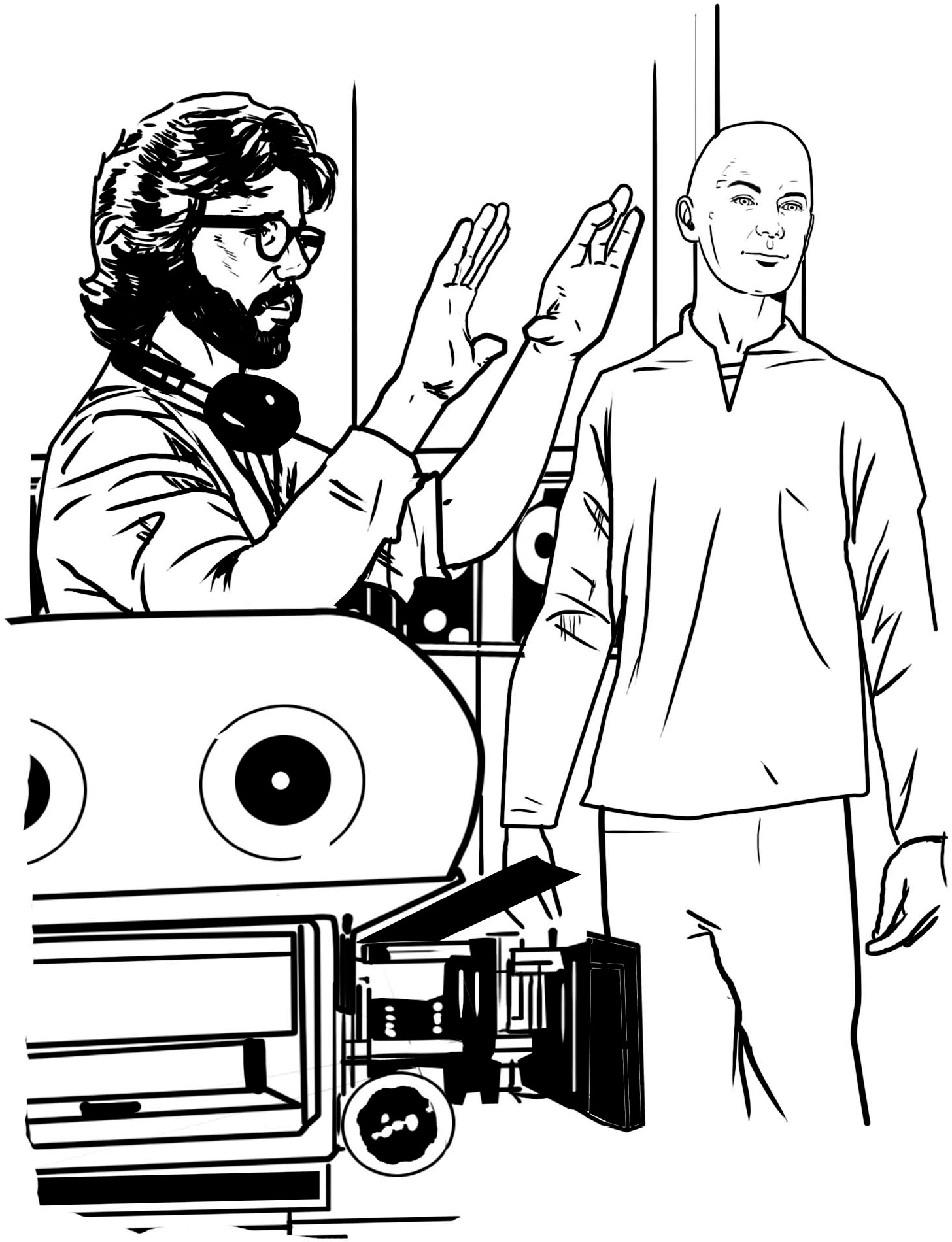

George graduated from USC on August 6, 1966, at twenty-two. He hoped to make documentaries—films that present actual events and facts, rather than made-up stories—or to become a cameraman. But young men George’s age were being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War. However, during his army physical he found out that he was diabetic. He could not be in the military. He could also no longer wash down chocolate bars with sugary soda. He returned to USC to attend graduate school in 1967. To pay his way he became a teacher’s assistant. At this time, the cinematography department had a contract to teach US Navy cameramen. George was assigned to teach the class in the evenings—and he got extra color film to make his own movies.

During the day he worked for Verna Fields, a top-notch editor, on a film about President Lyndon Johnson’s visit to Asia. The government wanted the film to make the president look good. Any shot that showed Johnson’s bald spot was cut. George hated other people telling him what to do. “I really wanted to be responsible for what was being said in a movie,” he said later.

George really liked Verna Fields’s assistant, Marcia Griffin. Marcia was a talented editor who fought her way into the male-dominated industry as an assistant. George had never had a real girlfriend, but he and Marcia soon began dating.

While teaching at night, George shot his own films during the day. His biggest project was Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB, the story of a man in a futuristic world. George called it a “science fiction documentary.” He recruited half his navy class as his crew. They were fascinated by his story of what life might be like in the future. It was a smash at student screenings. Aspiring filmmakers from all over California came to see it, including one from Long Beach State named Steven Spielberg.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hollywood was changing. George Lucas was one of a group of young film directors in New York and Los Angeles who were more daring and more experimental about the way they made movies. They helped each other, inspired each other, and competed with each other to make the best movies they could. To the businessmen who had ruled Hollywood for decades, they were just kids. Yet they were creating amazing films that were changing the way people thought about movies.

At the National Student Film Festival in 1967, Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB won the dramatic prize, and two other films by George won honorable mentions. He received a scholarship to Warner Bros. and was given a job helping another director at the studio. This was his chance to learn more about professional filmmaking. George Lucas had conquered the student film world. Now he was going to see what Hollywood was all about.