The Japanese had moved on the Minahassa Peninsula, the northernmost appendage of the oddly shaped island of Celebes.1 In the predawn hours of January 11, the Japanese 1st Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force had landed at the ports of Menado and Kema. They were supplemented by a pair of parachute drops, also by 1st Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force.2

Admiral Hart suspected that this landing would be a jumping off point for further attacks against southern Celebes, particularly the port of Kendari, the real strategic gem of the island. This meant that the Japanese transports – unarmored and vulnerable – would be an inviting target.

Hart moved to assemble a striking force. The cruisers Boise and Marblehead and the destroyers John D. Ford, Pope, Parrott, Paul Jones, Pillsbury, and Bulmer set up a rendezvous at Koepang on Timor, where the natives promptly made clear that the Americans were not wanted.3 The striking force was organized as Task Force 5 under the command of Admiral Glassford. Five of the destroyers would sail at night in column formation and launch all their torpedoes from their tubes on one side, then reverse course and launch all their torpedoes from the other side, filling the water with their deadly fish. Then the destroyers would leave, and the Marblehead, with Admiral Glassford on board, would fill the water with yet more torpedoes. Then she would use her 6in guns to enable everyone to withdraw. If they could not, the Boise, screened by the Pillsbury, could give cover with her 15 rapid-fire 6in guns.4

In theory this was a good plan; a high-speed torpedo attack at night, without the use of guns whose flashes would reveal the destroyers’ presence, could cause chaos and heavy damage among the enemy ships. Of course, night torpedo attacks were already standard in the Imperial Japanese Navy. In many respects, the US Navy (and, indeed, the Dutch) was playing catch up to the Japanese. But the logic behind leaving his single most powerful warship – the Boise – out of the action seems rather elusive.

On January 16 Task Force 5 began speeding up the hazardous Makassar Strait for Kema and their massed Japanese prey. And they were almost there when, on January 17, they received a report from the US submarines Pike and Permit, who had been sent in to scout the Kema area – the Japanese ships were gone. The attack was cancelled.5 Too soon, as it turned out: on January 21 the submarine Swordfish returned to Kema and found the harbor full of Japanese shipping. Her skipper Lieutenant Commander Chester Smith could not get into attack position, but he bided his time and was rewarded on January 24 when, just after noon, he managed to plunk two torpedoes into the gunboat Myoken Maru that sent her to the bottom.6

And so ended the first ABDAFLOAT attempt at a counterattack.

Admiral Glassford ordered his ships to retire to Koepang (Kupang) on Dutch Timor to refuel, which was much too far behind the front line for Admiral Hart’s liking.7 What Hart did not know was that the Marblehead suffered a turbine casualty while heading for Koepang, necessitating the shutdown of one of her propellers and limiting her speed to 28 knots.8 The refueling rendezvous was moved to Kebola Bay, on Alor Island just to the north of Timor.9

Also arriving for this refueling party were reinforcements: the John D. Edwards and Whipple; and, on January 17, the Houston, Alden, and Edsall.10 Now this was a striking force of some serious power. Admiral Hart had received a report from the Dutch that the Japanese were massing at the northern end of the Makassar Strait headed for Balikpapan with an estimated 16 transports, 12 destroyers, one light cruiser, and an unknown number of armed auxiliaries such as patrol boats and minesweepers.11 Hart ordered an attack. With his reinforcements in hand, Admiral Glassford adjusted his plan. Now all eight destroyers would accompany the Marblehead, while the Houston and Boise would remain 50 miles astern to use their guns to cover their withdrawal. The historian and US Navy commander Walter Winslow thought the plan was a “one-way ticket to oblivion” for the old Marblehead and the even-older destroyers.12

But oblivion would have to wait. The meeting in which Admiral Glassford presented his plan had not even concluded before they were told that the Dutch intelligence information was, as Admiral Hart would later call it, “wholly false” and the mission was scrubbed.13

And so ended the second ABDAFLOAT – rapidly earning the nickname “ABDAFLOP” – attempt at a counterattack.14

The assembled ships of Task Force 5 scattered to attend to other matters. The Houston was sent off with the John D. Edwards and Whipple for convoy duty.15 Late in the afternoon on January 18, the Trinity, with the Alden and Edsall as escorts, left Kebola Bay headed for Darwin and their encounter with I-123.16

On January 20, Dutch intelligence reported a Japanese advance down the Makassar Strait.17 US submarines were deployed in the Strait to try to peck at it as best they could. But the effort started off badly with the fatal grounding of S-36 off Makassar City. That night the submarines Porpoise, Pickerel, and Sturgeon moved to intercept the convoy in Makassar Strait, while the US submarines Spearfish, Saury, and S-40 and the Dutch submarines K-XIV and K-XVIII maneuvered into position off Balikpapan.18

Admiral Hart attempted to get Task Force 5 reassembled as best he could. With the Houston and her consorts gone on convoy duty, Task Force 5 was back to its original formidable configuration: light cruisers Boise and Marblehead and destroyers John D. Ford, Pope, Parrott, Paul Jones, Pillsbury, and Bulmer. Again, they rendezvoused at Koepang. Admiral Glassford’s battle plan was largely the same – Marblehead and five destroyers would go in for a night torpedo attack while Boise, screened by Bulmer, covered their withdrawal.

But the ABDA naval forces would continue to be plagued by operational accidents and mechanical breakdowns that would badly hamper their efforts against the Japanese. That plague would be no better exemplified than by this operation.

Back on January 18 the Marblehead had suffered a turbine casualty, reducing her speed to 28 knots. This was not good, but workable. Not so workable, however, was what had happened to the Boise, to which Admiral Glassford had been forced by the Marblehead’s issues to transfer his flag.19 While traversing the Sape Strait into the Flores Sea on January 21, the Boise struck an uncharted reef off Kelapa Island, an unfortunate incident that was the result of a lack of accurate navigational charts of the Indies as opposed to any negligence on the part of her skipper, Captain Stephen B. Robinson.20 The English language charts were often hundreds of years old, and with coral sometimes growing at a rate of 6in per year, the difference could be crucial. The Dutch had accurate charts, but they were in Dutch and the Americans could not read them. ABDAFLOAT could have used some of the Dutch navigational pilots, but the Dutch had none available, or so they said; Admiral Hart seemed less than completely convinced of the validity of that claim.21 Given Admiral Helfrich’s behavior, Hart had good reason to be suspicious.

But the upshot of the accident was disastrous. Boise suffered a 120ft gash in the port side of the keel. Her machinery was damaged by the subsequent flooding, water tanks were punctured, one of her condensers was filled with coral, and she would ultimately have to head to a British drydock in Bombay for repairs.22 So now arguably the most powerful ship in the already overmatched ABDAFLOAT, owing to her 15 rapid-fire 6in guns, and the only Allied warship in the Far East to have surface search radar was now out of this particular fight, never to return.

Admiral Glassford ordered the two cruisers, with the Pillsbury and Bulmer as escorts, to head for Waworado Bay on Soembawa, much to the disgust of Admiral Hart, who again thought they were too far out of position.23 There, on January 22, the Marblehead refueled from the damaged Boise, and Glassford transferred his flag back to the old cruiser.24 But in the interim, the Marblehead’s engine problems had proven to be far worse than initially thought – she had to limit her speed to 15 knots and shut down one shaft or the engine would be ruined.25 Now, Glassford’s two most powerful ships were maimed.

“Oh, for a little LUCK!” wrote Admiral Hart in his diary.26

Once the refueling was done, Boise and Pillsbury were ordered to Tjilatjap to determine the extent of the cruiser’s damage; the remaining four destroyers stayed in attack position near the Postillion Islands, while Marblehead and Bulmer were ordered to make for Soerabaja.27

So the initial formidable task force of three cruisers and eight destroyers had been pared down to all of four destroyers – John D. Ford, Pope, Parrott, and Paul Jones – of Destroyer Division 59 under the command of Commander Paul H. Talbot. Minimal though they were, they were all that was available, and Admiral Hart was determined to use them. For on January 22, the Japanese advance was confirmed. The Catalinas of Patrol Wing 10 had reported nine transports, four cruisers and 14 destroyers moving toward Balikpapan in small groups.28 The US submarine Pike reported 26 enemy transports, escorted by 14 destroyers, headed for Balikpapan.29 The submarine Sturgeon picked up the contact report and moved into attack position. After dark, her sonarman detected destroyers and a “heavy-screw ship” they thought was an aircraft carrier. Skipper Lieutenant Commander William Leslie “Bull” Wright launched four torpedoes. They heard hits and explosions. After hiding from the resulting Japanese antisubmarine counterattack for a while, Wright sent back a message: STURGEON NO LONGER VIRGIN, thinking he had sunk the carrier. In reality, there had been no carrier and the torpedoes had registered no hits – again.30

The withdrawal of the Marblehead and Bulmer was stopped and they were moved to a supporting position off the southeastern tip of Borneo. At 12:05 pm Admiral Hart gave the eagerly awaited order:

GOOD LUCK GOING IN … ATTACK ENEMY OFF BALIKPAPAN … IF NO CONTACTS BY 0400 ZONE TIME RETIRE AT BEST SPEED … GODSPEED COMING OUT.31

The key word was “attack.” The men of Destroyer Division 59 were elated to get the chance to strike back at the Japanese aggressors. But when the normally cool, capable Commander Talbot read the latest intelligence about the enemy numbers he was facing – “two cruisers, eight destroyers and possibly more plus transports” – he uttered two words: “My God.”32

The Japanese were not the only enemies Commander Talbot was facing. Talbot was suffering from severe pain and blood loss as a result of a particularly nasty case of hemorrhoids.33 Yet the choice between protecting one’s health and commanding the first US Navy surface battle since the Spanish–American War in 1898 was obvious. While the skipper and bridge crew of Talbot’s flagship John D. Ford were aware of the situation, Talbot kept his agony to himself and stayed in his command chair, however painful that may have been, to carry out his orders and protect his crews as best as his considerable ability would allow.

Talbot’s little group made a feint to the east, hoping to fool enemy scout planes into thinking the destroyers were headed for Menado Bay, Celebes. In this effort he was aided by a storm that was building as his ships continued onward. For one of the few times in the campaign, however, the Japanese scouts were nowhere to be seen.

At 7:30 pm, as the column approached Cape Mandar on Celebes, Talbot ordered a sharp column turn to port, course 310 degrees True.34 Destination: Balikpapan, keying on the position of the harbor’s lightship. By some miracle, these old flush-deckers managed to increase speed to 27 knots on a diagonal run across the Makassar Strait to the target. By blinker light, Talbot reiterated orders that he had issued that afternoon:

PRIMARY WEAPON TORPEDOES. PRIMARY OBJECTIVE TRANSPORTS. CRUISERS AS NECESSARY TO ACCOMPLISH MISSION. ENDEAVOR LAUNCH TORPEDOES AT CLOSE RANGE BEFORE BEING DISCOVERED … SET TORPEDOES EACH TUBE FOR NORMAL SPREAD. BE PREPARED TO FIRE SINGLE SHOTS IF SIZE OF TARGET WARRANTS. WILL TRY TO AVOID ACTION EN ROUTE … USE OWN DISCRETION IN ATTACKING INDEPENDENTLY WHEN TARGETS LOCATED. WHEN TORPS ARE FIRED CLOSE WITH ALL GUNS. USE INITIATIVE AND DETERMINATION.35

“Use initiative and determination” – music to a destroyerman’s ears.

The column was now heading into the teeth of a gale, battered by heavy winds and enveloped by rain, giant waves crashing over bows, tossing the little ships about, forcing the exposed gun crews under cover and splashing salt water on bridge windows.36 But slowly, almost imperceptibly, the water in the air was joined by something else: fog. Except that this was no normal fog; it was greasy, somewhat irritating, and had a burnt, chemical odor.37

After midnight, the lookouts reported seeing strange, surreal lights, some just a flash, others in the clouds. Off the starboard bow a large fire was observed on the water.38 Beyond it they could see an orange-red glow in the clouds with more fire on the horizon.

It was an environment worthy of Dante’s Inferno, but all too real. The fire on the water was the transport Nana Maru, set alight earlier that evening by a Dutch air attack of nine B-10 bombers from the Samarinda airfield, subsequently abandoned, and now serving as a midnight beacon guiding the four-pipers in to their target.39 The fog wasn’t just oily – it was oil. From the fire they could see ashore and, reflected in the clouds, Balikpapan’s burning oil fields, oil tanks, and oil refineries, with the storm winds blowing the smoke some 20 miles out over the Makassar Strait.40

The commander of the Japanese 56th Infantry Regiment and 2nd Kure Special Naval Landing Force Division had sent a message to the commander of the Dutch garrison at Balikpapan warning them not to damage the oil installations or they would “be killed without exception.”41 He may have hoped the record of the Imperial Japanese Army in China would be more effective in terrorizing the Dutch into acquiescence than it had been for the Chinese, but as had been the case in China, the threats backfired – literally. The Dutch may have been lacking in numbers and modern equipment, but they were not lacking in courage. They would rather die on their feet than live on their knees.42 There would indeed be reprisals for destruction of the oil facilities – severe reprisals – but the damage to the oil fields and refinery would delay the Japanese, a delay that would help the Allied war effort.43

Right now, the damage was both helping to cover the approach of the US destroyers with an effective if irritating smokescreen and providing another beacon to their target.

At 2:35 am, a lookout in the crow’s nest of the John D. Ford reported a column of four Japanese destroyers about 3,000yd ahead – a short distance, indicating that the rain and smoke were definitely hampering visibility on this already-moonless night – crossing from starboard to port.44 These destroyers had been the source of the strange lights, their searchlights reflecting off the clouds and flashing in the darkness.

Had the Americans been spotted? Is this why these big Japanese destroyers were now speeding by?

The gunners and torpedo crews on the old flush-deckers tensed, training their weapons on the Japanese and waiting for the order to fire. But the crews’ extensive training was paying off. These were professionals who would not panic. Talbot ordered a slight column turn to starboard (325 degrees True) to clear the enemy tin cans.

Three of the four Japanese destroyers passed by. The fourth passed and then flashed a challenge to the Americans. Using a blue light, the Japanese destroyer was essentially asking, “Who are you?”

Now surely the Americans had been found out. The US Navy sailors tensed, ready to fire. But Talbot coolly ignored the challenge and the American column disappeared into the glowing murk, while their Japanese rivals continued heading out to sea.45

Now where were the Japanese going?

The American column had sailed straight into the arms of the transports’ escorts, the Japanese 4th Destroyer Flotilla, under the command of Rear Admiral Nishimura Shōji. The flotilla comprised ten destroyers led by a light cruiser, as Japanese destroyer squadrons usually were, in this case the Naka.46 Nishimura was a competent, professional and steady if unspectacular commander.47 As the war progressed, however, he would reveal himself to be unable to adapt to changing circumstances or even to acknowledge them.48

But on this night, Admiral Nishimura had his 11 ships alert and ready for battle – with a submarine.

ABDAFLOAT’s dispatch of submarines to attack the invasion force was paying off. Unbeknownst to Talbot, on this night (and for once and arguably the only time in this naval campaign), the ABDA force was operating with something of a guardian angel. Lurking out to sea was the Dutch submarine K-XVIII, under the redoubtable and very talented Commander Carel Adrianus Johannes van Well Groeneveld, who was always willing to cause trouble. The boiling sea caused by the storm prevented use of her periscope, so K-XVIII had to run on the surface, where that same storm also prevented the normally excellent Japanese lookouts from seeing her. She managed to creep through the Japanese escorts to get a clean view of the best target available, the light cruiser Naka. K-XVIII fired four torpedoes from her bow tubes at Admiral Nishimura’s flagship. There were no successful hits. But the Japanese transport Tsuruga Maru was hit by one of van Well Groeneveld’s torpedoes at about 12:45 am.49 It is not clear, but the torpedo that hit the Tsuruga Maru may have come from the same round that had sped past the Naka.50

The plucky submarine was rapidly becoming a menace to the Japanese ships. Admiral Nishimura ordered the 4th Flotilla eastward out into the strait to hunt down the bothersome K-boat, which was exactly what the naval textbooks said he should do, unless he also had a column of enemy destroyers bearing down on the flock he was supposed to protect. So these ten destroyers and one light cruiser went off into the strait to make life difficult for Commander van Well Groeneveld and easy for Commander Talbot. After sailing straight into the arms of the Japanese 4th Destroyer Flotilla, the Americans sailed straight out again. The door was unguarded and wide open. And through it sailed the US destroyers with their eager crews, who could not believe their luck.

“In battle, victory goes to the brave,” said the John D. Ford’s gunnery officer Lieutenant William P. Mack.51 Then Mack added, “the fool-hardy.”52 The K-XVIII went to ground. Commander van Well Groeneveld had been warned of a pending attack by US destroyers and did not want to become involved in any friendly fire incidents. The Dutch submarine submerged, sitting down to watch the show and report on the results.

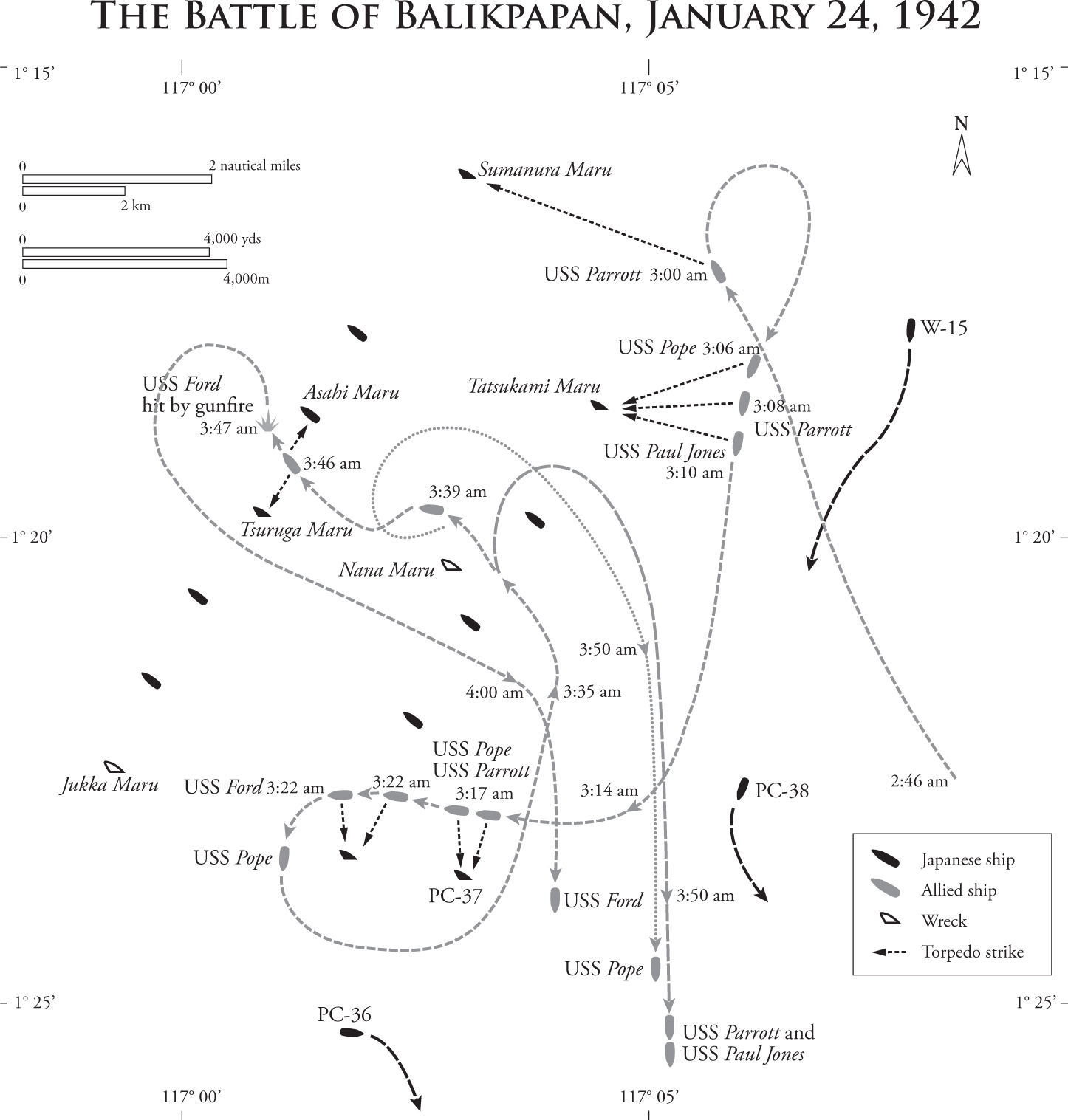

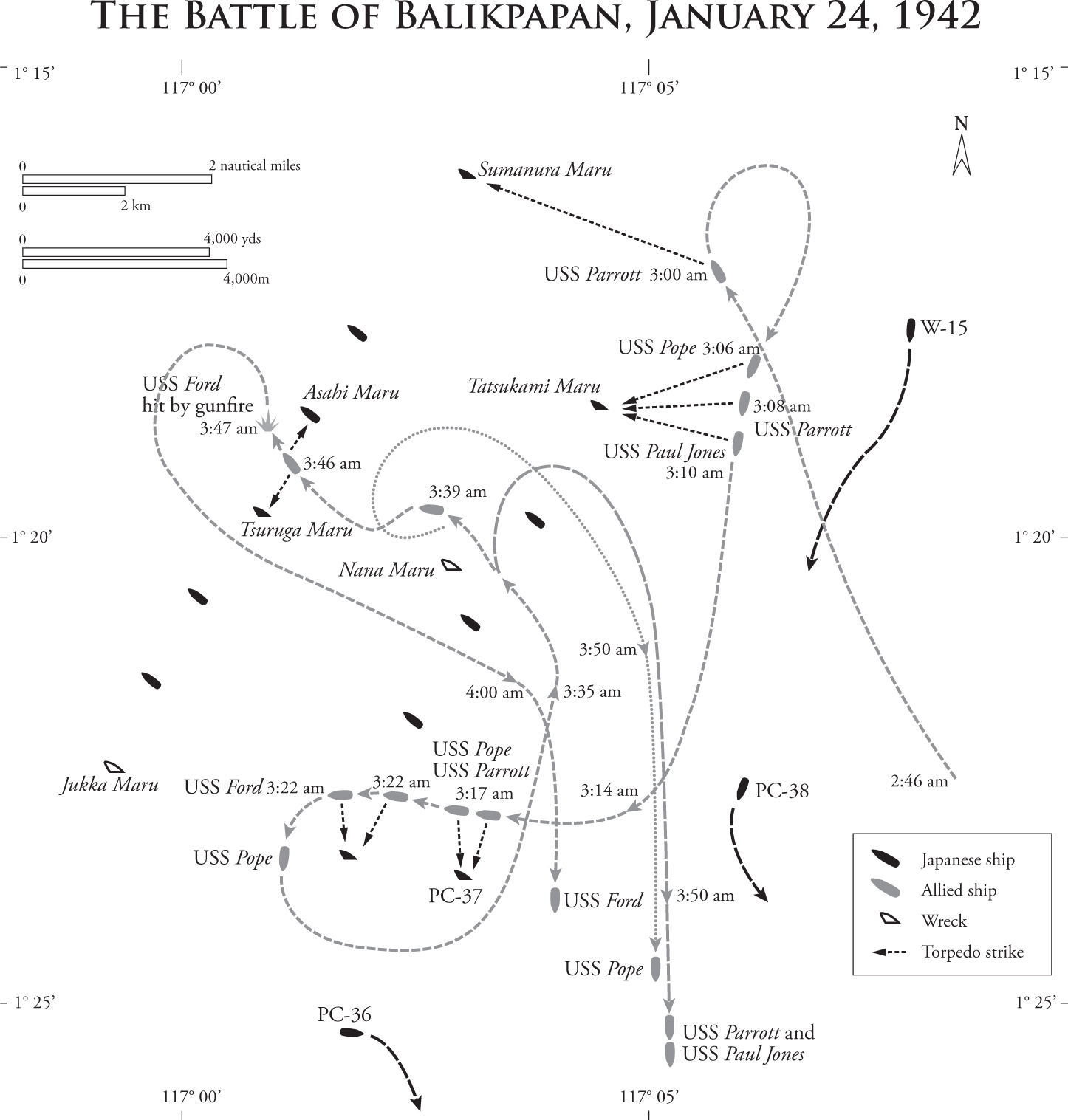

It was around 2:45 am that the sneaking American destroyers sighted their targets: the Japanese transports, sitting in two parallel lines roughly southwest to northeast, some 5 miles outside the harbor of Balikpapan: motionless and silhouetted by the massive fires ashore.53 Guarding them were only three patrol boats converted from World War I-vintage destroyers, four minesweepers, and four subchasers.54 As if on cue, the angry seas calmed down; the four-pipers had entered the lee of Balikpapan. It was time for Paul Talbot and company to go to work. The American column turned to the north to make a high-speed pass at the outer line of five transports. Their torpedo tubes had been trained outward for some time; now the destroyers selected their targets and let their torpedoes loose.

The Parrott fired three torpedoes from her portside tubes at a Japanese transport. It was motionless, backlit, a perfect setup. The Americans counted down the time to when their deadly fish should strike but there was no resulting explosion. About two minutes later, the Parrott thought she had spotted a destroyer or maybe a cruiser heading away some 1,000yd to starboard; that is, seaward of the American column. She let loose with five torpedoes from her starboard batteries. Yet again there was no explosion.

This was a frustrating experience by itself, made even more so by the fact that two of the torpedoes had been fired unintentionally. Even worse, her target had been neither a destroyer nor a cruiser, but the 700-ton minesweeper W-15. It was not a valuable target, to be sure, but no one should hold it against the Parrott’s crew; target identification was always difficult even on a sunny day, let alone on a stormy, smoky night. The W-15 herself made the not-uncommon mistake of believing the American destroyer to be the flagship Naka, until she spotted a second Naka and then a third and a fourth. She radioed the actual Naka, but before W-15 could take any other action, the ships seemingly disappeared.55

The Ford launched one torpedo from her port tubes at an anchored transport astern. The transport was immobile and unsuspecting – but yet again there was no explosion.

The Paul Jones fired one torpedo at a target to starboard, which turned out to be the W-15, who was attracting a lot of attention for a minesweeper. The US sailors counted down to … nothing.

Ten torpedoes launched at short range but with no hits. The destroyermen had heard stories that the submarine’s torpedoes were defective. Were their own torpedoes defective as well?

It was now about 3:00 am. The US column had now passed the Japanese transports to the north, and Talbot, frustrated but not discouraged, ordered a column turn to starboard to make another pass. Just before she turned, the aggressive Parrott sighted a target to starboard and launched three torpedoes. Once again, the countdown began.

Finally. One large explosion, maybe more, right on target – the 3,519-ton transport Sumanoura Maru, at the north end of the inner line of transports. The minesweeper W-16, at the northern end of the transports, saw the explosion and, nearby, a shadow moving south. She raced to help, but before she arrived the transport had sunk, with only nine survivors.56

The hit also alerted the Japanese that they were under attack. The transports and their close escorts started signaling each other and getting under way. In their confusion they even signaled the US destroyers, thus unwittingly giving away their positions.57 The W-15 tried to alert Admiral Nishimura that surface forces were attacking, but the admiral refused to believe that enemy ships could penetrate the anchorage. He believed the attack must be coming from the same submarine he was hunting.58

Talbot was in good position to take advantage of the Japanese confusion. The American destroyer column was compact and unified, making anyone not in the column a target. The column was also between groups of enemy ships in conditions of low visibility. The normal Japanese excellence in night spotting was hampered not only by the smoke, clouds, and lack of a moon, but also by the oil fires on the coast that crippled night vision. With the American ships now threading their way among the Japanese ships, the defending escorts would have severe problems identifying the Americans without risking friendly fire incidents. The bigger question for the Americans was how long could they keep their formation compact and unified in the low visibility?

The Ford led the column southward again at around 3:00 am. Talbot ordered a cut in speed; maybe they would have better luck if they proceeded more slowly.

Once again, the elderly tin cans of the US Navy slashed at the outer Japanese transport column. One unfortunate target silhouetted to starboard attracted five torpedoes from Pope at 3:06 am, then Parrott fired one more at 3:08 am, and Paul Jones fired yet another at 3:10 am.59 The destroyers were not coordinating their targets so, instead of spreading their torpedoes out on multiple targets, they were wasting torpedoes by inadvertently targeting the same ships. In this case, however, all seven torpedoes may have been needed. They resulted in exactly one hit; but that hit created a spectacular explosion as the 7,064-ton ammunition ship Tatsukami Maru, already damaged by that Dutch air raid earlier in the day, sank.60

At 3:14 am the John D. Ford stopped slashing at the outer Japanese line and led a column turn to starboard to stab at the inner transport line. Five minutes later, the Pope fired two torpedoes from her port tubes at what appeared to be a destroyer less than 2,000yd away; Parrott fired three torpedoes at the same target. In the dark and smoke, the target had the appearance of a destroyer, and indeed she had been once long ago, but due to obsolescence she had lost her name Hishi and was converted to a patrol boat – PB-37. Allegedly damaged earlier by the K-XVIII, the unfortunate little patrol boat was now overwhelmed with three torpedo hits, two near the bow and one near the stern, which sent her to the shallow bottom of Balikpapan harbor.61

At this point the 5,175-ton freighter Kuretake Maru got under way. At 3:22 am Ford and Paul Jones each fired one torpedo at the freighter from their port tubes at a range of about 1,000yd. Because she was under way, Kuretake Maru had power to maneuver and managed to evade the torpedoes. No matter. Talbot led the column on a loop around the freighter and back outside the outer column of transports. Paul Jones took one more shot, a single torpedo that found its mark and put the Kuretake Maru under. Ford finished her loop around the stricken freighter and led the column back north.

Pope, Parrott, and Paul Jones now signaled: ALL TORPEDOES EXPENDED.62 Pursuant to his previous orders, Talbot ordered them to commence firing with their 4in guns. All three engaged multiple targets to port. The low visibility, which even a starshell fired by the Parrott could not overcome, prevented any confirmation of damage claims.63

Keeping ships together during night combat operation is extremely difficult and after having stayed together for almost an hour, the American column now disintegrated. At 3:35 am the flagship Ford turned northwest, around the still burning hulk of the Nana Maru, now standing on end, and went back through the outer line of transports.64 Then, at 3:40 am, the Ford swung sharply to port and slowed down for reasons that remain disputed; the ONI Narrative says that she believed that she was entering a minefield (although it gives no reason why), but her gunnery officer later indicated that it was to avoid colliding with a sinking transport.65 Pope had to swerve to port to avoid the flagship, Parrott and Paul Jones swung to starboard to avoid the Ford and whatever wreck was in the way. Parrott and Paul Jones then looped around, settling on a course to the south and breaking off the action. The Pope passed the stopped Ford, then circled to starboard around the flagship and followed her two sister ships out of the action.

Talbot was not quite finished. The John D. Ford started moving once again and at 3:46 am fired her last two torpedoes at a group of three transports. When her gunnery officer Lieutenant Mack got the order to “Commence firing,” he began unloading on the Japanese at ranges of 500–1,500yd, so close that no complicated targeting mechanics were needed. At the same time, the Tsuruga Maru, earlier damaged by the K-XVIII, now went to a watery grave in a ball of fire, sunk by the last torpedoes of the Ford.

But that particular victory was short-lived. The Ford’s next target transport, Asahi Maru, was armed. For a few minutes the Ford’s topside crew watched uneasily as shells from the freighter fell like a textbook creeping barrage, getting closer and closer with each strike.66 When the Ford was straddled the crew knew what was coming; at 3:47 am, a shell hit the destroyer’s aft deckhouse, setting fire to gasoline and starshell ammunition nearby and wounding four men, none seriously.67 The hit caused the Ford to leave a trail of fire like a rocket, but within 30 seconds the burning materials were jettisoned.68 They continued to burn on the water and even attracted Japanese fire. The Ford then turned the tables on her assailant and riddled the Asahi Maru with gunfire as she passed, wounding 50 men. Next target for her guns was the Tamagawa Maru, which received ten 4in shell hits.

Now the Ford was getting close to shoal water. Concerned about running aground, the destroyer made a port turn and doubled back. Her lookout reported no visible targets. With torpedoes expended and her destroyer consorts gone, the Ford’s captain asked for permission to withdraw. Talbot was reluctant. “If we had the other ships we could go back in. I’m not sure the torpedoes did too much good. The 4-inchers were much more impressive, but then Ford has pressed it’s [sic] luck too long, permission granted.”69

The Ford’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander Jacob E. Cooper, now ordered the destroyer to make a hard turn to starboard, course 180 degrees True, and wanted all the speed the engine room could provide.70 At one point, the John D. Ford was reported to have been going almost 32 knots, the fastest she had gone since her sea trials.71 By 4:00 am, she was heading south along the Borneo coast looking to rejoin her sister four-pipers. They were certain that the Japanese would chase them, with their light cruiser and the Fubuki-class destroyers.

The Americans needn’t have worried. Admiral Nishimura believed that the voluminous gunfire and starshells had come from that same annoying submarine. At 4:08 am he radioed the P-36 asking if she was mistaking his destroyers for the enemy. As late as 4:20 am the Naka and her destroyers were still some 7,000yd east of the transports.72

The Japanese already faced long odds in catching the American destroyers. Though the sky was beginning to lighten in the east, to the west it was still dark; between that darkness, the smoke, and the night vision crippled by the fires, they would have had difficulty spotting the four-pipers against the backdrop of the coast of Borneo. Eventually, the Naka and destroyers Minegumo and Natsugumo arrived on the scene but found no enemy ships. Nishimura remained convinced that this was all the work of that meddling K-XVIII; Naka’s after-action report discusses only the action with the Dutch submarine and nothing about the American destroyers.73

The K-XVIII had not wrought havoc inside Balikpapan Harbor, but she did have a role to play. Commander van Well Groeneveld had taken his submersible to periscope depth to watch, with considerable amusement, the chaos caused by the American Destroyer Division 59; he left only when, in his words, “I saw that my friends were doing very well.”74 Admiral Hart was very pleased. Now all that remained of this operation was to get Destroyer Division 59 back to port. He radioed Admiral Glassford in the Marblehead to look for their return.75

Talbot continued speeding south as fast as the ancient engines on the John D. Ford would go. But that did not diminish the magnitude of their accomplishment. At 6:42 am the Ford caught up with her consorts, and the Parrott, Paul Jones, and Pope now fell in behind the flagship. Talbot ordered a signal flag hoisted on the Ford: WELL DONE.76

The lookouts remained on constant scan for the Japanese pursuit – the ships that were bigger, faster, and better armed than the American four-pipers with the floatplanes that would herald the ships’ approach. Their fears seemed realized when, at 7:10 am, a floatplane was sighted,77 except that it came from the south and flashed a message: its mother ship Marblehead was 50 miles to the south and coming to meet them.

By 8:00 am the relieved destroyers were under the limping light cruiser’s protection. Admiral Glassford greeted them with a flag signal: WELL DONE.78 A rather happy Admiral Hart sent a wireless message of his own: WELL DONE.79 Repetitive these messages may have been, but after a combat operation, especially one in a war going as badly as this one, there can never be too many such messages. The kudos was badly needed and very much welcomed.

Commander Talbot would not make it to Soerabaja, at least not sitting in his command chair. Weakened by stress, lack of sleep, pain and blood loss, he collapsed while climbing the ladder down from the bridge to the well deck. But a victory can salve many wounds and ease many stresses. On Task Force 5’s return to Soerabaja, the Royal Netherlands naval officers and men, who had been suspicious and slightly contemptuous of their American counterparts after their flight from the Philippines, were now friendly, enthusiastic, and helpful.

Now the critiquing began, however, and there was a lot of it, doing little to improve the frosty relationship between Admiral Hart and Admiral Glassford. Hart wondered what Glassford had been doing by keeping his ships in Koepang and Waworado. If he had kept them closer to the front line, maybe he would not have lost the use of the Boise. Glassford wanted more credit for the victory, even though he had been more than 100 miles away from the action, because he had developed the battle plan. He was also angry that Hart had sent the attack order to Commander Talbot himself rather than through Glassford as was proper for the chain of command. So furious was Glassford that in his private diary he declared either he or Hart would have to go.80

But by far the most painful criticism was implied: the four destroyers had actually sunk only four of 12 relatively unguarded transports.

And there really was no answer for that. Commander Talbot took some heat because the high speed of his initial run was thought to have impaired the accuracy of the torpedoes. Talbot made no excuses whatsoever, only saying that the high speed is what allowed his destroyers to escape. This was a hit and run operation, after all.

But Admiral Hart knew something else was at work, something that was not the fault of Commander Talbot or even Admiral Glassford, something far more serious than slightly imperfect tactics. They had heard stories from the submarine crews about the lack of success against the enemy, their complete frustration and loss of confidence. The submarines, the destroyers, possibly the aircraft carrier pilots as well, they all had a traitor in their midst … their torpedoes. Simply put, their torpedoes did not work.

Still, for now, the Allies had achieved their badly needed victory. It may have only delayed the Japanese advance by at most a single day, but it was still a victory. The US Navy, in its antiquated, outnumbered, and isolated ships in the Far East, could still hold its own against the Imperial Japanese Navy.